CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS

The following are the diagnostic guidelines for AD, VaD, DLB, and FTLD (the four most common causes of dementia in order). Also presented are the guidelines for diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which bridges the spectrum between dementia and normal cognition.

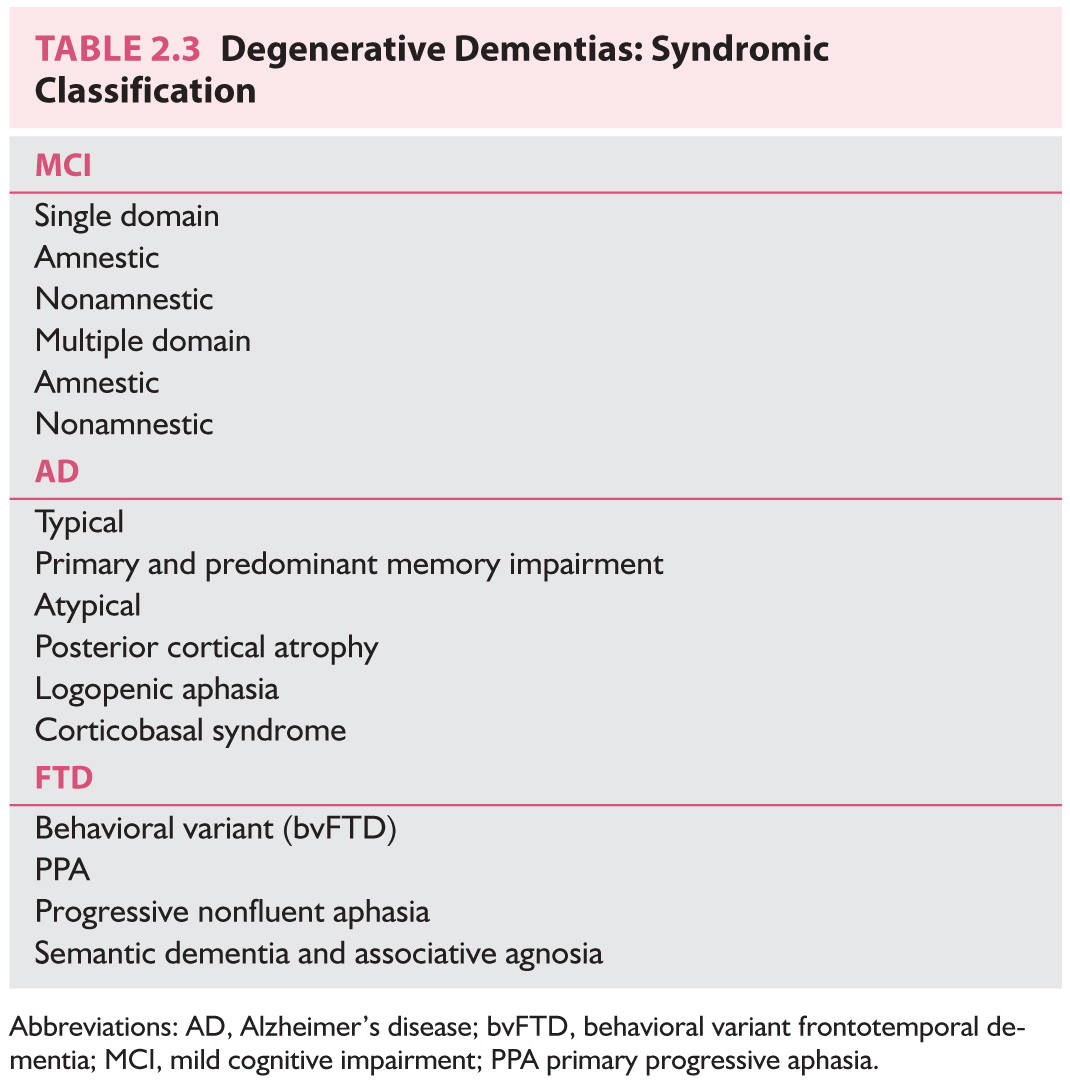

A. Alzheimer’s disease. AD is characterized by both amyloid and tau pathology. The National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer and Related Diseases Association 1984 criteria for the diagnosis of AD have recently been modified to take into account (1) Patients with the pathophysiologic process of AD, which can be found in those with normal cognition, MCI, and AD. This pathophysiologic process, designated as AD-P, is thought to begin years before the diagnosis of clinical AD. (2) The diagnostic criteria for other diseases such as LBD and FTD. (3) MRI, positron emission tomography (PET) for imaging the amyloid beta protein (Aß), 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET, and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers Aß42, total tau and phophotau. (4) Other clinical syndromes that do not present with amnesia but are related to AD pathology including posterior cortical atrophy and logopenic aphasia. (5) The dominantly inherited AD causing mutations in amyloid precursor protein, presenilin-1, and presenilin-2 (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, respectively). (6) A change in age cutoffs noting persons under 40 and over 90 may have the same AD-P. (7) Many persons with possible AD in the past are now designated MCI.

In what follows, we present the 1984 criteria for probable and possible AD. Patients who meet the 1984 criteria for probable AD still meet criteria for probable AD. Additionally, we present the proposed new 2011 criteria for AD in Section A.8 under Criteria for Diagnosis.

1. Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of probable AD.

a. Dementia established by means of clinical examination and documented with the Mini-Mental State Examination, Blessed Dementia Rating Scale, or other similar examination and confirmed with neuropsychological tests.

b. Deficits in two or more areas of cognition.

c. Progressive worsening of memory and other cognitive function.

d. No disturbance of consciousness.

e. Onset between the ages of 40 and 90 years, most often after 65 years.

f. Absence of systemic disorders or other brain diseases that in and of themselves could account for the progressive deficits in memory and cognition.

2. Supporting findings in the diagnosis of probable AD.

a. Progressive deterioration of specific cognitive functions such as aphasia, apraxia ![]() (Video 2.1), or agnosia.

(Video 2.1), or agnosia.

b. Impaired activities of daily living and altered patterns of behavior.

c. Family history of similar disorders, particularly if confirmed neuropathologically.

d. Laboratory results as follows:

(1) Normal results of lumbar puncture (LP) as evaluated with standard techniques.

(2) Normal or nonspecific electroencephalography (EEG) changes (increased slow-wave activity).

(3) Evidence of cerebral atrophy at computed tomography (CT) with progression documented by means of serial observation.

3. Other clinical features consistent with the diagnosis of probable AD, after exclusion of causes of dementia other than AD.

a. Plateaus in the course of progression of the illness.

b. Associated symptoms of depression; insomnia; incontinence; delusions; illusions; hallucinations; catastrophic verbal, emotional, or physical outbursts; sexual disorders; and weight loss.

c. Other neurologic abnormalities for some patients, especially those with advanced disease, and including motor signs such as increased muscle tone, myoclonus, or gait disorder.

d. Seizures in advanced disease.

e. CT findings normal for age.

4. Features that make the diagnosis of probable AD uncertain or unlikely.

a. Sudden, apoplectic onset.

b. Focal neurologic findings such as hemiparesis, sensory loss, visual field deficits, and incoordination early in the course of the illness.

c. Seizures or gait disturbance at the onset or early in the course of the illness.

5. Clinical diagnosis of possible AD.

a. May be made on the basis of the dementia syndrome, in the absence of other neurologic, psychiatric, or systemic disorders sufficient to cause dementia and with variations in onset, presentation, or clinical course.

b. May be made in the presence of a second systemic or brain disorder sufficient to produce dementia, which is not considered to be the principal cause of the dementia.

c. Should be used in research studies when a single, gradually progressive, severe cognitive deficit is identified in the absence of any other identifiable cause.

6. Criteria for the diagnosis of definite AD are the clinical criteria for probable AD and histopathologic evidence obtained from a biopsy or autopsy.

7. Classification of AD for research purposes should specify features that differentiate subtypes of the disorder such as familial occurrence, onset before 65 years of age, presence of trisomy 21, and coexistence of other relevant conditions such as Parkinson’s disease.

8. Proposed new criteria for AD. In 2011, National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association work group suggested new criteria for AD based on clinical and research evidence. All patients who met the 1984 criteria for probable AD described in A.1 would meet the current criteria. In addition, the following criteria are proposed:

a. Probable AD dementia with increased level of certainty. This category includes patients with “probable AD dementia with documented decline” and “probable AD dementia in a carrier of a causative AD genetic mutation in APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2 genes.”

b. Possible AD dementia. This category includes patients with an “atypical course” or “mixed etiology” and would not necessarily meet the 1984 criteria for possible AD. “Atypical course” is characterized by “sudden onset, insufficient historical detail or objective cognitive documentation of progressive decline.” “Mixed etiology” includes subjects with concomitant cerebrovascular disease or features of DLB or “evidence for another neurologic disease or a non-neurologic medical comorbidity or medication use that could have a substantial effect on cognition.”

c. Probable or possible AD dementia with evidence of the AD pathophysiologic process. These criteria are proposed only for research purposes and incorporate the use of biomarkers, which are not yet advocated for routine diagnostic use. These biomarkers fall into the two categories of “brain amyloid ß (Aß) protein deposition,” that is, low CSF Aß42 and positive PET amyloid imaging; and “downstream neuronal degeneration or injury,” that is, elevated CSF tau, decreased FDG uptake on PET in temporoparietal cortex, and disproportionate atrophy on structural MRI in medial, basal, and lateral temporal lobe, and medial parietal cortex. The biomarker profile will fall into clearly positive, clearly negative, and indeterminate categories.

B. Vascular dementia. There are different published diagnostic criteria for VaD: NINDS-AIREN (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-Association Internationale pour la Recherche et L’Enseignement en Neurosciences), ADDTC (State of California Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers), DSM-IV, and Hachinski Ischemia Scale. Their distinct features lead to differences in sensitivity and specificity. The first set of criteria discussed is the NINDS-AIREN criteria for VaD and is as follows:

1. The criteria for probable VaD include all of the following:

a. Dementia defined similarly to DSM-IV criteria.

b. Cerebrovascular disease defined by the presence of focal signs on neurologic examination, such as hemiparesis, lower facial weakness, Babinski’s sign, sensory deficit, hemianopia, and dysarthria consistent with stroke (with or without history of stroke), and evidence of relevant cerebrovascular disease at brain imaging (CT or MRI), including multiple large-vessel infarcts or a single strategically situated infarct (angular gyrus, thalamus, basal forebrain, or posterior or anterior cerebral artery territories), as well as multiple basal ganglia and white matter lesions and white matter lacunes or extensive periventricular white matter lesions, or combinations thereof.

c. A relation between the two previous disorders manifested or inferred from the presence of one or more of the following: (1) onset of dementia within 3 months after a recognized stroke, (2) abrupt deterioration in cognitive functions, or (3) fluctuating, stepwise progression of cognitive deficits.

2. Clinical features consistent with the diagnosis of probable VaD include the following:

a. Early presence of a gait disturbance.

b. History of unsteadiness and frequent, unprovoked falls.

c. Early urinary frequency, urgency, and other urinary symptoms not explained by urologic disease.

d. Pseudobulbar palsy.

e. Personality and mood changes, abulia, depression, emotional incontinence, or other subcortical deficits, including psychomotor retardation and abnormal executive functioning.

3. Features that make the diagnosis of VaD uncertain or unlikely include the following:

a. Early onset of memory and other cognitive functions, such as language, motor skills, and perception in the absence of corresponding lesions at brain imaging.

b. Absence of focal neurologic signs other than cognitive disturbance.

c. Absence of cerebrovascular lesions on CT scans or MRIs.

4. The term AD with cerebrovascular disease should be reserved to classify the condition of patients fulfilling the clinical criteria for possible AD and who also have clinical or brain imaging evidence of relevant cerebrovascular disease.

5. The criteria for definite VaD are as follows:

a. Probable VaD, according to core features.

b. Cerebrovascular disease by histopathology.

c. Absence of neurofibrillary tangles or neuritic plaques exceeding those expected for age.

d. Absence of other clinical or pathologic disorders capable of producing dementia.

6. Vascular dementia: ADDTC criteria for VaD are as follows:

a. The criteria for probable VaD include all of the following:

(1) Dementia by DSM-III-R criteria.

(2) Two or more strokes by history/examination and/or CT or T1-weighted MRI, or single stroke with clear temporal relationship to onset of dementia.

(3) Presence of at least one infarct outside cerebellum by CT or T1-weighted MRI.

b. The criteria for possible VaD include all of the following:

(1) Dementia by DSM-III-R criteria.

(2) Single stroke with temporal relationship to dementia or Binswanger defined as the following: (1) early-onset incontinence or gait disturbance not explained by peripheral cause, (2) vascular risk factors, and (3) extensive white matter changes on neuroimaging.

c. The criteria for mixed dementia are as follows:

(1) Evidence of AD or other disease on pathology examination plus probable, possible, or definite ischemic VaD.

(2) One or more systemic or brain diseases contributing to patient’s dementia in the presence of probable, possible, or definite ischemic VaD.

d. The criteria for definite ischemic VaD are as follows:

(1) Dementia.

(2) Multiple infarcts outside the cerebellum on neuropathology exam.

7. Vascular dementia: DSM-IV criteria for VaD are as follows:

a. Impaired memory.

b. Presence of at least one of the following: aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or impaired executive functioning.

c. Symptoms impair work, social, or personal functioning.

d. Symptoms do not occur solely during delirium.

e. Cerebral vascular disease has probably caused the above deficits, as judged by laboratory data or by focal neurologic signs and symptoms.

8. Vascular dementia: Hachinski Ischemic Scale for VaD assigns points to each criterion. A total score >7 corresponds to multi-infarct dementia, whereas <4 is interpreted as AD. Each of the following criteria is shown with the associated number of points in parentheses.

a. Abrupt onset (2)

b. Stepwise progression (1)

c. Fluctuating course (2)

d. Nocturnal confusion (1)

e. Relative preservation of personality (1)

f. Depression (1)

g. Somatic complaints (1)

h. Emotional incontinence (1)

i. History of hypertension (1)

j. History of strokes (2)

k. Associated atherosclerosis (1)

l. Focal neurologic symptoms (2)

m. Focal neurologic signs (2)

C. DLB is defined pathologically by the presence of cortical Lewy bodies composed mainly of α-synuclein and is part of a spectrum with Parkinson’s disease, which has brainstem Lewy bodies. The McKeith criteria for the clinical diagnosis of DLB are as follows:

1. Progressive cognitive decline interferes with normal social and occupational functioning

2. Deficits on tests of attention, executive function, and visuospatial functioning are often prominent

3. Prominent or persistent memory impairment may not be present early in the course of illness

4. Two of the following core features are necessary for the diagnosis of probable DLB, and one is necessary for possible DLB:

a. Fluctuating cognition or alertness

b. Recurrent visual hallucinations

c. Spontaneous features of parkinsonism

5. Suggestive features. ≥1 suggestive feature + ≥1 core feature are sufficient for the diagnosis of probable DLB; ≥1 suggestive feature and no core features are sufficient for the diagnosis of possible DLB; probable DLB should not be diagnosed on the basis of suggestive features alone.

a. REM sleep behavior disorder

b. Severe neuroleptic sensitivity

c. Low-dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia demonstrated by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or PET imaging

6. Features supportive of the diagnosis are repeated falls, syncope or transient loss of consciousness, severe autonomic dysfunction, tactile or olfactory hallucinations, systematized delusions, depression, relative preservation of mesial temporal lobe structures on CT/MRI, reduced occipital activity on SPECT/PET, low uptake meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy, prominent slow-wave activity on EEG with temporal lobe transient sharp waves.

7. The following features suggest a disorder other than DLB:

a. Cerebrovascular disease evidenced by focal neurologic signs or cerebral infarcts present on neuroimaging studies

b. The presence of any other physical illness or brain disorder sufficient to account in part or in total for the clinical picture

c. If parkinsonism appears only for the first time at a stage of severe dementia

8. Temporal sequence of symptoms. DLB should be diagnosed when dementia occurs before or concurrently with parkinsonism (if it is present). The term Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) should be used to describe dementia that occurs in the context of well-established Parkinson’s disease.

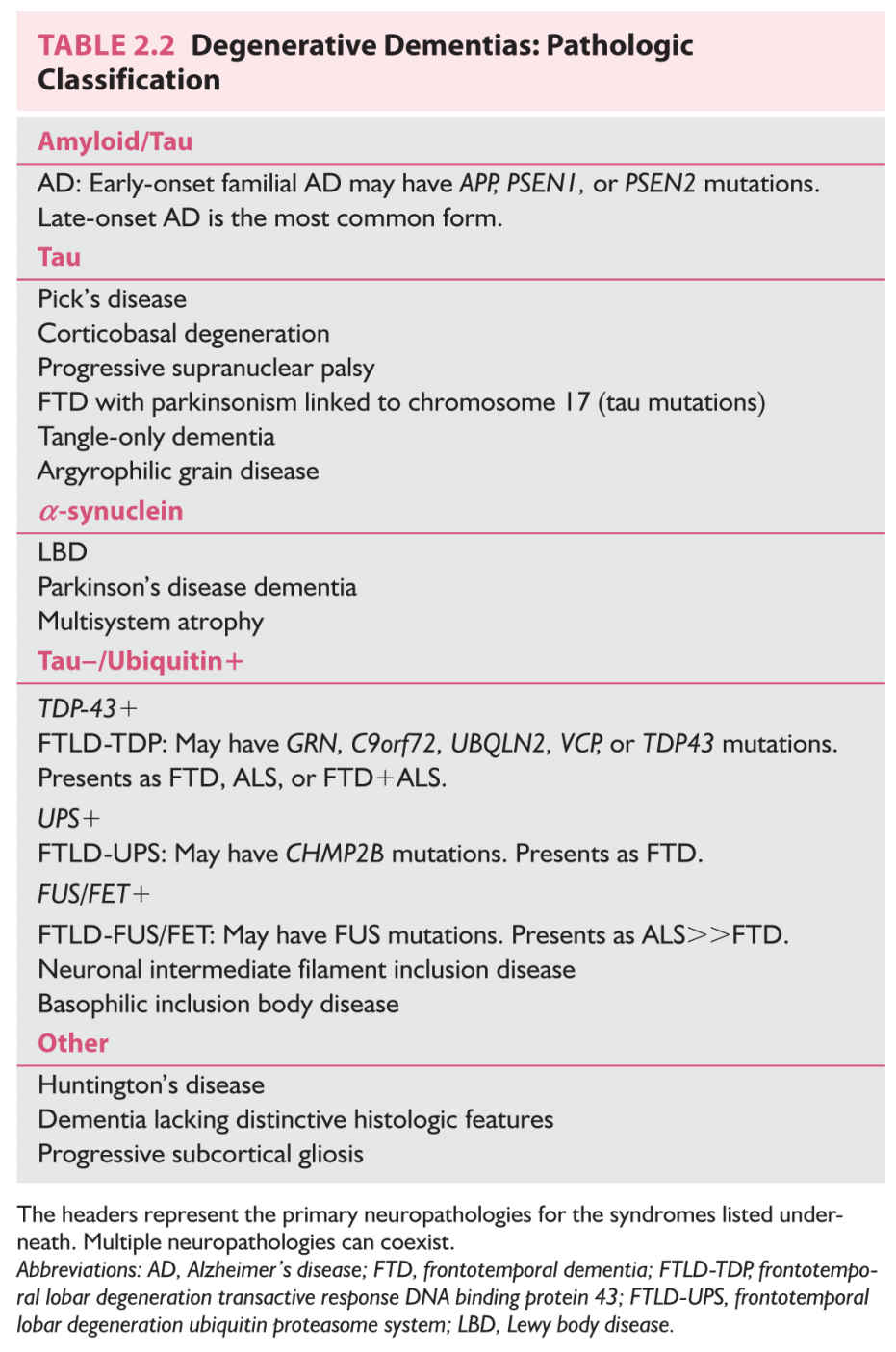

D. FTLD involves focal atrophy of the frontal or temporal lobes or both, the distribution of atrophy determining the clinical presentation. The age at onset tends to be slightly younger (often before 65 years) than that for AD. Patients with clinical FTLD usually do not have Alzheimer’s-type pathologic findings, but instead have other distinct pathology. According to recent consensus recommendations, there are five major neuropathologic classifications for FTLD based on the presence of abnormally accumulating protein as follows: FTLD-tau (includes Pick’s disease and FTDP-17), FTLD-TDP (transactive response DNA binding protein 43; includes familial FTLD due to mutations in GRN, C9orf72, UBQLN2, VCP, or TDP43), FTLD-UPS (ubiquitin proteasome system; includes familial FTLD due to mutations in CHMP2B), FTLD-FUS/FET (fused in sarcoma; includes neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease, basophilic inclusion body disease, familial FTLD due to FUS mutations), and FTLD-ni (no inclusions).

The two major phenotypes of FTLD are behavioral variant (bvFTD) and primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Three main variants of PPA are defined as nonfluent/agrammatic, semantic, and logopenic. International bvFTD Criteria Consortium (FTDC) published their first report on the comparison of 1998 Neary et al. criteria and their proposed criteria, which identified greater sensitivity. The proposed 2011 FTDC criteria for bvFTD need further evaluation, and are as follows: Possible bvFTD requires three of six clinically discriminating features (disinhibition, apathy/inertia, loss of sympathy/empathy, perseverative/compulsive behaviors, hyperorality, and dysexecutive neuropsychological profile). Probable bvFTD also includes functional disability and characteristic neuroimaging; and bvFTD with Definite FTLD requires histopathologic evidence of FTLD or a pathogenic mutation.

In comparison, the 1998 Neary’s criteria for the clinical diagnosis of bvFTLD are as follows:

1. In FTD, character change and disordered social conduct are the dominant features initially and throughout the disease course. Instrumental functions of perception, spatial skills, praxis, and memory are intact or relatively well-preserved. Core criteria are as follows:

a. Insidious onset and gradual progression.

b. Early decline in social interpersonal conduct.

c. Early impairment in regulation of personal conduct.

d. Early emotional blunting.

e. Early loss of insight.

2. Supportive diagnostic features of FTD are as follows:

a. Decline in personal hygiene and grooming.

b. Mental rigidity and inflexibility.

c. Distractibility and impersistence.

d. Hyperorality and dietary changes.

e. Perseverative and stereotyped behavior.

f. Utilization behavior.

g. Speech and language features: aspontaneity and economy of speech; press of speech, stereotypy of speech, echolalia, perseveration, and mutism.

h. Physical signs: primitive reflexes, incontinence, akinesia, rigidity, tremor, low and labile blood pressure.

i. Investigations: Neuropsychology-significant impairment on frontal lobe tests in the absence of severe amnesia, aphasia, or perceptuospatial disorder; EEG-normal; imaging-predominant frontal or anterior temporal abnormality.

Gorno-Tempini et al. have provided new classification and criteria for the PPA variants. It should be noted that while most PPA-nonfluent/agrammatic variant has FTLD-tau, most PPA-semantic variant has FTLD-TDP, and most PPA-logopenic variant has AD pathology, a definitive clinicopathologic correlation cannot be established. Thus, the following criteria represent clinical classifications.

(1) Diagnosis of PPA requires that the following criteria be met.

(a) Difficulty with language as the most prominent clinical feature.

(b) Daily activities

impaired primarily owing to language impairment.

(c) Aphasia as the most prominent early deficit.

(d) Deficit not accounted for by other disorders.

(e) Deficit not accounted for by psychiatric diagnosis.

(f) No prominent initial episodic memory, visual impairments.

(g) No prominent initial behavioral disturbance.

(2) Clinical diagnosis of PPA-nonfluent/agrammatic variant.

At least one of the following core features must be present:

(a) Agrammatism in language production.

(b) Effortful, halting speech with inconsistent speech sound errors and distortions (apraxia of speech). At least two of three of the following other features must be present:

(1) Impaired comprehension of syntactically complex sentences.

(2) Spared single-word comprehension.

(3) Spared object knowledge.

(3) Imaging-supported PPA-nonfluent/agrammatic variant diagnosis.

Both of the following criteria must be present:

(a) Clinical diagnosis of nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA.

(b) Imaging must show one or more of the following results:

(1) Predominant left posterior frontoinsular atrophy on MRI.

(2) Predominant left posterior frontoinsular hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT or PET.

(4) PPA-nonfluent/agrammatic variant with definite pathology.

Clinical diagnosis (criterion a below) and either criterion b or c must be present.

(a) Clinical diagnosis of nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA.

(b) Histopathologic evidence of a specific neurodegenerative pathology (e.g., FTLD-tau, FTLD-TDP, AD, and others).

(c) Presence of a known pathogenic mutation.

(5) Clinical diagnosis of PPA-semantic variant.

Both of the following core features must be present:

(a) Impaired confrontation naming.

(b) Impaired single-word comprehension. At least three of the following other diagnostic features must be present.

(1) Impaired object knowledge, particularly for low-frequency or low-familiarity items.

(2) Surface dyslexia or dysgraphia.

(3) Spared repetition.

(4) Spared speech production (grammar and motor speech).

(6) Imaging-supported PPA-semantic variant diagnosis.

Both of the following criteria must be present:

(a) Clinical diagnosis of semantic variant PPA.

(b) Imaging must show one or more of the following results:

(1) Predominant anterior temporal lobe atrophy.

(2) Predominant anterior temporal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT or PET.

(7) PPA-semantic variant with definite pathology.

Clinical diagnosis (criterion a below) and either criterion b or c must be present.

(a) Clinical diagnosis of semantic variant PPA.

(b) Histopathologic evidence of a specific neurodegenerative pathology (e.g., FTLD-tau, FTLD-TDP, AD, and others).

(c) Presence of a known pathogenic mutation.

(8) Clinical diagnosis of PPA-logopenic.

Both of the following core features must be present.

(a) Impaired single-word retrieval in spontaneous speech and naming.

(b) Impaired repetition of sentences and phrases. At least three of the following other features must be present:

(1) Speech (phonologic) errors in spontaneous speech and naming.

(2) Spared single-word comprehension and object knowledge.

(3) Spared motor speech.

(4) Absence of frank agrammatism.

(9) Imaging-supported PPA-logopenic diagnosis.

Both criteria must be present.

(a) Clinical diagnosis of logopenic variant PPA.

(b) Imaging must show at least one of the following results:

(1) Predominant left posterior perisylvian or parietal atrophy on MRI.

(2) Predominant left posterior perisylvian or parietal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on SPECT or PET.

(10) PPA-logopenic with definite pathology.

Clinical diagnosis (criterion a below) and either criterion b or c must be present.

(a) Clinical diagnosis of PPA-logopenic.

(b) Histopathologic evidence of a specific neurodegenerative pathology (e.g., AD, which is the most common pathology, FTLD-tau, FTLD-TDP, and others).

(c) Presence of a known pathogenic mutation.

E. MCI is the transitional state between normal aging and dementia, and represents a condition with greater rate of progression to dementia than normal aging. Patients with amnestic MCI progress to AD at a rate of 10% to 15% per year. Initial criteria for MCI required the presence of memory impairment. Current criteria also recognize nonamnestic forms of MCI.

1. Criteria for MCI are as follows. Cognitive impairment that is not normal for aging, represents a decline, does not reach criteria for dementia, and does not impair activities of daily living.

2. Subtypes of MCI are as follows. Depending on the presence or absence of memory impairment and presence of one or more cognitive impairments, there are four types of MCI. Memory impairment present: amnestic MCI versus nonmemory cognitive impairment: nonamnestic MCI. Single domain (one domain impaired only) versus multiple domain. It is proposed that the expected outcome of single or multiple domain amnestic MCI is AD, of single or multiple domain nonamnestic MCI is less likely to be AD, although this is possible, and could be FTD or DLB.

3. New proposed research criteria for MCI. These criteria incorporate the use of biomarkers as described in A.8.c. When both Aβ and neuronal injury biomarkers are “positive” in a subject with MCI, it is suggested that these subjects have the highest likelihood of progressing to AD dementia; hence, the terminology of “MCI due to AD-High likelihood” is proposed. When only one set of biomarkers is positive, “MCI due to AD-Intermediate likelihood” and when both are negative, “MCI-Unlikely due to AD” is suggested. Additional work is needed for the validation of these criteria and standardization of biomarkers.

EVALUATION

A. History. It is essential that the history be obtained not only from the patient but also from an independent informant. In most cases the patient can be told, “I am now going to ask your spouse some questions, and if your spouse makes any errors, feel free to make corrections.” Sometimes, the informant may not want to speak openly in front of the patient, so the clinician may want to arrange a separate interview, perhaps while the patient is undergoing another test or later by telephone.

1. Patient difficulties. Determine what difficulties the patient is having and what family members have noticed. Commonly, a patient with dementia may not know there is a memory difficulty or be able to give accurate details of the problem. Begin by asking the patient an open-ended question such as “What problems are you having?” This often does not elicit the desired responses. Even with specific questions such as “Are you having difficulty with your memory?” the clinician may not be told what the problems are. The informant may have to be asked specific questions, such as “What can’t the patient do now that he (or she) could do before?” or “Does the patient sometimes ask the same question more than once in the same conversation?”

2. Time course. The time the family first noticed problems and the course the disease has taken over time are critical factors in the evaluation. A disease that is slowly progressive fits the profile of a degenerative disease such as AD. A disease that starts suddenly or follows a stepwise progression would be more in keeping with VaD. Rapidly progressive dementia (over a few months) suggests Creutzfeldt–Jakob’s disease.

3. Functioning of the patient. Determine how well the patient has been functioning at work and at home, including performance of the basic activities of daily living. Patients with MCI are by definition able to function well. Patients with progressive nonfluent aphasia or semantic dementia usually are also able to function well. Ask what the patient does to keep busy. Does he or she read the newspaper, watch the news on television, keep the checkbook, do the shopping, prepare the meals, take part in a sport or hobby? Knowing this information helps in the planning of questions to ask during the mental status part of the examination.

4. Issues of safety. Ask whether the patient drives. If so, has the patient ever become lost while driving or had any accidents, near-accidents, or traffic violations? If the patient prepares meals, has he or she ever left the stove on? Does the patient keep weapons, and if so, has this posed any danger to the patient or to others?

5. Etiologically directed history. Include a history of vascular disease and risk factors, head injury, toxic exposure, symptoms of infection or exposure to diseases such as tuberculosis, psychiatric history such as depression, symptoms of depression (such as a change in weight, insomnia, crying, or anhedonia), medications, systemic illnesses, other past illnesses, and alcohol or tobacco use.

The following questions may bring out symptoms of DLB: Does the patient have good days and bad days? What specifically cannot the patient do on bad days? Does the patient see things that are not there (visual hallucinations)? Does the patient act out dreams at night (rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder)? Look for personality and behavioral changes in FTD with specific questions—for example, Does the patient drive recklessly, such as run stop signs or speed? Has the patient developed poor table manners such as eating excessively fast? Does the patient have rituals or do things repetitively?

6. Family history. Ask what the patient’s parents died of and at what ages. Ask specifically whether there were memory problems in the later years. Then ask about the ages and health of the patient’s siblings and children. Patients with late-onset AD commonly have a family history of disease. A strong family history for a younger patient suggests an autosomal dominant disease such as familial AD, familial FTLD, Huntington’s disease, or spinocerebellar ataxia.

B. Physical examination.

1. Give a standardized short mental state test, such as the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination or the Short Test of Mental Status. Asking about news events is a highly sensitive measure of recent memory. Be sure that the patient has been exposed to this information. Ask questions such as, Who is the president? What is his wife’s name? Who was the last president? What is his wife’s name? Note any evidence of aphasia, apraxia, or agnosia. Anomia with preservation of orientation suggests semantic dementia. Observe for lack of insight and disinhibited behaviors that occur in FTD.

2. Look for cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, arterial bruits, arrhythmia, and heart murmur.

3. Complete a full neurologic examination. Pay special attention to focal deficits such as visual field cuts, paresis, sensory loss, and ataxia. Posterior cortical atrophy, which most commonly has Alzheimer’s-type pathology begins as progressive visual dysfunction similar to that of Balint’s syndrome. Evaluate for any extrapyramidal difficulties, such as hypokinesia, increased muscle tone, a mask-like face, and micrographia. Determine whether the patient has any problem in walking. This is often best undertaken in the hallway rather than in the examining room. Note the patient’s step size, speed of walking, arm swing, and ability to turn. The palmomental reflex and snout reflex are not particularly helpful because they are common among healthy elderly. The grasp reflex occurs late in the course of the disease.

C. Laboratory studies.

1. Recommended in all cases are complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thyroid and liver function tests, folate and vitamin B12 levels, syphilis serologic testing, CT or MRI, and neuropsychological evaluation.

2. Recommended selectively are electroencephalography, LP, chest radiograph, HIV test, drug screen, SPECT or PET, heavy metal screen, copper, or ceruloplasmin.

3. Electroencephalography can be useful in diagnosing Creutzfeldt–Jakob’s disease, differentiating depression or delirium from dementia, evaluating for encephalitis, revealing seizures as causes of memory difficulties, and diagnosing nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

4. LP is recommended if the patient is suspected of having a paraneoplastic or limbic encephalopathy, cancer, CNS infection; hydrocephalus is seen at imaging; the patient is younger than 55 years; the dementia is acute or subacute; the patient is immunosuppressed; or vasculitis or connective tissue disease is suspected. In the setting where it is important to make a specific diagnosis, CSF amyloid b and tau protein levels jointly are reported to be 89% sensitive and 90% specific for AD. In the setting when Creutzfeldt–Jakob’s disease is suspected often because the MRI diffusion image shows cortical ribboning or basal ganglia involvement, CSF 14-3-3 protein and CSF tau measurements plus the newer RT-QuIC (real-time quaking-induced conversion) are helpful.

5. FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose)-PET scan can be useful in differentiating FTD from AD. In one blinded study in which FDG-PET was used to evaluate those patients with and those without dementia, the sensitivity was only 38%, and the specificity was 88%. Also, biparietal hypometabolism supports the diagnosis of AD but is not specific.

6. Amyloid PET scan. There are now three FDA-approved isotopes for imaging brain Ab deposition. Many of the present studies evaluating Ab antibody to treat or prevent AD include only patients who have evidence of brain Ab deposits on amyloid PET scan. In this way, these drugs are accurately targeted, and those with non-AD dementias are excluded. When there is a disease-modifying treatment or disease preventative therapy, amyloid PET studies are expected to be used more often.

7. Other diagnostic biomarkers. The ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E gene (apoE4) is a well-established risk factor for AD; however, the American Medical Association does not recommend apoE4 testing in the diagnosis of AD or if the patient’s condition is presymptomatic. Mutations in the PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP genes can cause early-onset, autosomal dominant AD and are commercially available for testing. Genetic counseling is required before and after mutation testing. Structural imaging techniques including voxel-based morphometry, hippocampal volumetric measurement; functional imaging techniques including f-MRI, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and amyloid PET imaging in the brain are emerging as imaging techniques with potential use for differentiating various dementia types and for preclinical diagnoses.

8. Longitudinal biomarkers. As mentioned earlier, these biomarkers are included in the new criteria for presymptomatic AD, MCI, and AD dementia, although additional research is needed for their validation and standardization. Longitudinal assessment of CSF amyloid ß and tau protein, PET amyloid imaging, FDG-PET, and MRI volumetric studies lead to the hypothetical model of dynamic biomarker changes in AD, which posits the following order of changes: decrease in CSF amyloid ß, increase in PET amyloid, increase in CSF tau and phospho-tau, decrease in MRI hippocampal volume and FDG-PET activity, cognitive impairment. Studies in asymptomatic carriers of early-onset familial AD mutation carriers suggest that changes in CSF biomarkers occur 15 to 20 years before symptom onset. Development of PET tracers to follow brain tau accumulation will be an important additional biomarker tool. These biomarkers will serve as valuable tools in tracking response to disease-modifying therapies once they become available.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Be aware of the possible causes of dementia listed in Table 2.1. The most important reversible causes include depression, medication, hydrocephalus, thyroid disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, fungal infection, neurosyphilis, subdural hematoma, and brain tumor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by National Institute of Aging grant P50 AG16574-02 and the State of Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative. NET is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 NS080820, U01 AG046139, RF1 AG051504, and R21 AG048101.

• Neurodegenerative diseases constitute the most common etiology of dementia, but potentially reversible etiologies can also exist.

• AD is the most common dementia etiology, accounting for 50% to 75% of the cases, followed by VaD (20% to 30%), FTD (5% to 10%), and DLB.

• In addition to a thorough history and physical examination, blood tests for reversible causes of cognitive decline (including CBC, chemistry panel, vitamin B12 levels, thyroid, liver, kidney function tests), CT or MRI, and neuropsychological examination are needed for diagnosis, management, and counseling.

• Patients with atypical presentations, such as young age of onset, sudden onset, rapid progression, systemic illness, presence of noncognitive symptoms or signs, may require additional testing, such as EEG, LP, FDG-PET, or additional laboratory studies.

• AD typically presents as progressive worsening in memory, but atypical presentations with predominant involvement of other cognitive domains also exist.

• Clinical features that suggest DLB include fluctuations, hallucinations, parkinsonism, REM sleep behavior disorder, and neuroleptic sensitivity.

• FTD can present with predominant behavioral abnormalities or language impairment.

• Subjects with MCI have intact activities of daily living, but this condition can be a prodrome for dementia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree