Approach to the Patient with Lower Extremity Pain, Paresthesias, and Entrapment Neuropathies

Gregory Gruener

Lower extremity pain and paresthesia are common symptoms of peripheral nervous system (PNS) disorders. Diagnosing a mononeuropathy requires that the motor, reflex, and sensory changes be confined to a single nerve and can, if necessary, be supported by electrodiagnostic studies (EDS).

Diagnosis and management of PNS disorders was once the sole domain of specialists. However, “reemergence” of generalists in health care has resulted in at least two major trends. The first, as expected, is that persons with such disorders are no longer under the sole care of a specialist. The second, somewhat “unintentional” effect, is that the role of specialists has become more demanding. Specialists need to develop a greater proficiency in differentiating neuropathy from radiculopathy, plexopathy, and other nonneurologic syndromes of pain, disturbed sensation, or weakness. This increasing competency occurs in the setting of fewer and more carefully selected laboratory investigations.

Fortunately, recognition of a neuropathy has always necessitated careful attention to the history and examination, skills that are expected of specialists, but “within reach” of a generalist. After localization, a ranking of potential etiologies is formulated, and further diagnostic evaluation is planned.

This chapter provides an outline of common as well as some infrequent forms of lower extremity neuropathy. Symptoms and findings are emphasized, and the most frequent etiologic considerations are mentioned. The importance of bedside examination is assumed throughout, but the application of diagnostic tests is also reviewed.

I. EVALUATION

A. History.

Various aspects of the history help in narrowing the etiologies of a mononeuropathy. The nature of onset (abrupt or insidious), preceding events (injury, surgery, or illness), associated symptoms (fever, weight loss, or joint swelling), and aggravating or alleviating features (joint position or specific activities) are all important. Because the observed deficit can be similar regardless of etiology, historical information is instrumental in limiting the differential diagnosis.

B. Physical examination. Although motor and sensory symptoms and signs correspond to the distribution of a single peripheral nerve or branch, the degree of deficit and constellation of findings can vary. Motor signs may be clinically absent, or varying degrees of weakness, atrophy, or fasciculation may be found. Likewise, sensory symptoms can be positive (e.g., tingling, pricking, and burning), negative (hypesthesia), or, while corresponding to a sensory distribution of a nerve, may be most pronounced in its distal distribution. Therefore, the sensory examination should begin with the patient’s description of the area of involvement. The course of the nerve should be evaluated and local areas of discomfort or the presence of a Tinel’s sign (pain or paresthesia in the cutaneous distribution of a nerve elicited by light percussion over that nerve) sought. The relationship of sites of discomfort to adjacent anatomic structures helps in identifying sites of nerve entrapment or compression.

C. Diagnostic studies. Further evaluation may be necessary in confirming the presence and severity of a mononeuropathy and excluding more proximal sites of involvement (plexus or root) that can clinically mimic a mononeuropathy.

1. EDS. An EMG and nerve stimulation studies (NSS) are quite useful in the evaluation of mononeuropathies. They can aid in localization, detect bilateral but asymmetric nerve

involvement (or detect an underlying polyneuropathy), define severity, and provide prognostic information.

2. Laboratory testing is directed at identification of a systemic or generalized disease that may be a predisposing factor and with newer imaging techniques, at times, targeted fascicular nerve biopsy. Owing to the practical nature of this section, an exhaustive listing of the medical, systemic diseases or structural disorders that can cause a mononeuropathy is not provided. The Recommended Readings provide extensive tabulations of frequent as well as unusual etiologies.

3. Imaging studies. Radiographic imaging was previously undertaken to identify intrathoracic, abdominal, retroperitoneal, or pelvic masses that may lead to nerve root, plexus, or nerve injury, but now it is also applied to imaging the PNS directly. This role of imaging studies has considerably advanced now that MRI is the method of choice for delineating a focal site of involvement, characterizing and at times assisting in the diagnosis of a nerve lesion. However, its effectiveness not only depends on the necessary MRI hardware and software, but clinical expertise through an interdisciplinary and collaborative effort among physicians and clinical departments. Routine X-ray studies play a less significant role.

II. SPECIFIC FORMS OF MONONEUROPATHY

A. Femoral and saphenous neuropathy. Formed within the psoas muscle by fusion of the posterior divisions of the ventral rami of the L2-4 spinal nerves, the femoral nerve exits from the lateral border of the psoas and descends between it and the iliacus muscles (which it may also innervate), but under the fascia of the iliacus. Emerging under the inguinal ligament, lateral to the femoral artery, the nerve divides into motor branches, which supply the quadriceps muscles, and sensory branches to the anterior portion of the thigh (Figure 25.1). One major division, the saphenous nerve, descends medially within Hunter’s (adductor) canal, accompanying the femoral artery. At the medial superior aspect of the knee, it emerges from the canal and, accompanying the saphenous vein, descends medially down the leg and ends at the medial aspect of the foot. The saphenous nerve supplies the sensory innervation to the medial aspect of the leg and foot.

1. Etiology. Femoral neuropathy is usually caused by trauma from surgery (intrapelvic, inguinal, or hip operations), stretch or traction injuries (prolonged lithotomy position in childbirth), or direct compression (hematoma within the iliacus compartment). Although diabetes mellitus is described as a frequent etiologic factor, such cases are misnomers and represent a restricted plexopathy or more diffuse lesions, but predominantly affecting femoral nerve function. Saphenous neuropathy is most often attributable to injury following surgery (peripheral vascular, saphenous vein removal, or knee operations).

2. Clinical manifestations.

History. The patient reports leg weakness (as if the leg will “fold under”) on attempting to stand or walk. Pain in the anterior part of the thigh accompanied by the abrupt onset of leg weakness is a frequent presentation of an iliacus (retroperitoneal) hematoma. A similar pattern of pain, but usually subacute in onset, can be observed in cases of “femoral neuropathy” occurring in diabetes mellitus. With the exception of pain, sensory involvement tends to be infrequent and a minimal symptom of femoral neuropathy.

Because of its association with surgery, sensory loss in saphenous neuropathy may initially go unnoticed or be of little concern to the patient. However, pain may be prominent, and in such cases, it usually appears sometime after the assumed injury to the nerve.

Physical examination.

Neurologic. Examination reveals weakness of the quadriceps muscles, absent or diminished patellar reflex, and sensory loss over the anterior thigh and, with saphenous nerve involvement, the medial aspect of the leg and foot.

General. Examination or palpation within the inguinal region and, in cases of saphenous nerve involvement, the medial aspect of the knee may identify focal areas of pain and perhaps the site of involvement. The proximity of a surgical scar or point of injury can provide additional etiologic clues. In cases in which retroperitoneal hemorrhage is suspected, peripheral pulses may be normal, but there is characteristic posturing of the leg (held flexed at the hip), and attempts to extend or perform a reverse straight-leg test exacerbate the pain.

3. Differential diagnosis. Discovery of hip adduction weakness suggests a more proximal process, plexus or root as the site of involvement, although a superimposed obturator neuropathy cannot be excluded.

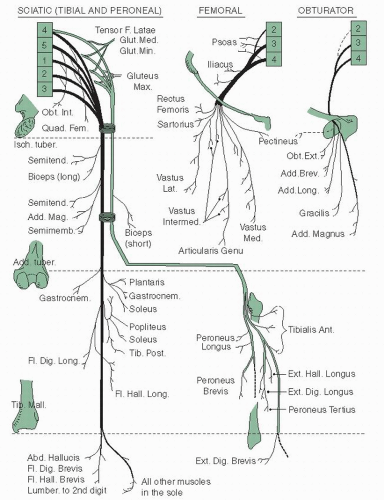

FIGURE 25.1 Motor distribution of the nerves of the lower limb. (Modified from Basmajian JV. Grant’s Method of Anatomy. 9th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1975.) |

4. Evaluation.

Electrodiagnostic. NSS are not as helpful as EMG in the evaluation of a suspected femoral neuropathy. EMG includes study of other L2-4 innervated muscles and paraspinal muscles because they should not be involved in isolated femoral neuropathy.

Imaging. CT or MRI of the retroperitoneum helps to identify cases resulting from retroperitoneal hemorrhage or suspected mass lesion.

B. Obturator neuropathy.

Arising within the psoas muscle from ventral divisions of the L2-4 spinal nerves, the obturator nerve exits from the psoas muscle at its lateral margin, descends into the pelvis, and exits through the obturator foramen. It innervates the gracilis, adductor magnus, longus, and brevis muscles and supplies sensation to the upper medial aspect of the thigh.

1. Etiology. Isolated neuropathy of the obturator nerve is unusual. In cases resulting from pelvic or hip fracture, involvement of other nerves to the lower extremity or lumbosacral plexus also occur. Benign and malignant pelvic masses can result in obturator neuropathy, as can surgical procedures performed on those masses or within the pelvis.

2. Clinical manifestations.

History. Leg weakness and difficulty walking are the most common first symptoms and usually overshadow sensory loss, if present.

Physical examination.

Neurologic. Motor evaluation shows weakness of hip adduction, and sensory loss may be found along the upper medial thigh. The patellar reflex should be intact.

General. Careful pelvic and rectal examinations can identify an intrapelvic tumor and are necessary when obturator paralysis occurs without trauma.

3. Differential diagnosis. The presence of hip flexor or knee extensor weakness or an impaired patellar reflex suggests a lumbosacral plexopathy or L3-4 radiculopathy. In addition, sensory loss, which extends below the knee, is inconsistent with the expected sensory deficit.

4. Evaluation.

Electrodiagnostic. NSS are not as helpful as EMG where involvement of other L2-4 muscles or paraspinal muscles identifies a more proximal lesion.

Imaging. When obvious trauma is not a consideration, radiological imaging of the pelvic cavity is helpful when a mass or infiltrative lesion is suspected.

C. Lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy.

Dorsal divisions of the ventral primary rami of the L2-3 spinal nerves contribute to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, which emerges from the lateral border of the psoas major muscle. It then crosses laterally, within the fascia of the iliacus muscle, and crosses over the sartorius muscle before passing under the lateral border of the inguinal ligament. Piercing the fascia lata, it divides into anterior and posterior branches that provide sensory innervation to the anterolateral aspects of the thigh. Anatomic variation is frequent in regard to origin (it can arise as a branch of the femoral or genitofemoral nerve), course of its branches and extent of its sensory innervation.

1. Etiology. In most cases, entrapment or compression at or near the inguinal ligament is the assumed etiologic factor. However, entrapment or compression at other sites (i.e., retroperitoneal mass), surgical procedures (especially those involving retroperitoneal structures, pelvis, or inguinal sites), and trauma to the thigh can also injure the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

2. Clinical manifestations.

History. Pain (burning or a “crawling” sensation) with variable loss of sensation on the anterolateral aspects of the thigh and exacerbated by walking or arising from a chair (meralgia paresthetica). Frequently, the patient rubs the thigh for relief.

Physical examination.

Neurologic. The area of sensory change usually is small and over the lateral aspect of the thigh.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree