Working memory depends on the integrity of the frontal lobes. More specifically, recent functional imaging studies have linked working memory to the dorsolateral prefrontal sector of the frontal lobes. A laterality effect has also been noted wherein verbal working memory tasks depend on the left dorsolateral prefrontal sector, whereas spatial tasks depend on the right dorsolateral prefrontal sector.

A. Anterograde and retrograde memory.

1. Anterograde memory refers to the capacity to learn new information—that is, to acquire new facts, skills, and other types of knowledge. It is closely dependent on neural structures in the mesial temporal lobe, especially the hippocampus and interconnected structures, such as the amygdala, the entorhinal and perirhinal cortices, and other parts of the parahippocampal gyrus.

2. Retrograde memory refers to the retrieval of information that was acquired previously—that is, retrieval of facts, skills, and other knowledge learned in the recent or remote past. This type of memory is related to nonmesial sectors of the temporal lobe, including the polar region (Brodmann’s area 38), the inferotemporal region (including Brodmann’s areas 20, 21, and 36), and the occipitotemporal region (including Brodmann’s area 37 and the ventral parts of areas 18 and 19). Autobiographical memory, a special form of retrograde memory that refers to knowledge about one’s own past, is linked primarily to the anterior part of the nonmesial temporal lobes, especially in the right hemisphere.

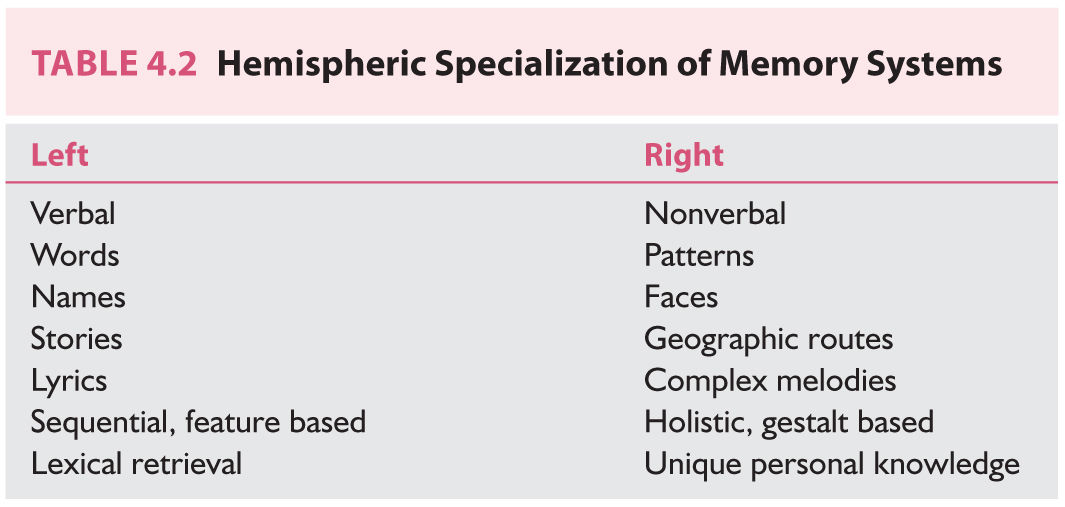

B. Verbal and nonverbal memory. Knowledge can be divided into that which exists in verbal form, such as words (written or spoken) and names, and that which exists in nonverbal form, such as faces, geographic routes, and complex musical patterns. This distinction is important because it is generally believed that the memory systems in the two hemispheres of the human brain are specialized differently for verbal and nonverbal material (Table 4.2). Specifically, systems in the left hemisphere are dedicated primarily to verbal material, and systems in the right hemisphere are dedicated primarily to nonverbal material. This arrangement parallels the general arrangement of the human brain, in which the left hemisphere is specialized for language and the right hemisphere for visuospatial processing. This distinction applies to almost all right-handed persons and to approximately two-thirds of left-handed persons. (In the remaining minority of left-handers, the arrangement may be partially or completely reversed.)

C. Declarative and nondeclarative memory.

1. Declarative memory (also known as explicit memory) refers to knowledge that can be “declared” and brought to mind for conscious inspection, such as facts, words, names, and individual faces, which can be retrieved from memory, placed in the “mind’s eye,” and reported. The acquisition of declarative memories is intimately linked to the functioning of the hippocampus and other mesial temporal lobe structures.

2. Nondeclarative memory (also known as implicit memory) refers to various forms of memory that cannot be declared or brought into the mind’s eye. Examples include sensorimotor skill learning, autonomic conditioning, and certain types of habits. Nondeclarative memory requires participation of the neostriatum, cerebellum, and sensorimotor cortices. A remarkable dissociation between declarative and nondeclarative learning and memory has been repeatedly found among patients with amnesia (including those with Korsakoff’s syndrome, bilateral mesial temporal lobe lesions, medial thalamic lesions, and AD). Among such persons, sensorimotor skill learning and memory are often preserved, whereas declarative memory is profoundly impaired.

D. Short- and long-term memory.

1. The term short-term memory is used to designate a time span of memory that covers from 0 to approximately 45 seconds, a brief period during which a limited amount of information can be held without rehearsal. Also known as primary memory, it does not depend on the hippocampus or other temporal lobe memory systems but is linked closely to cerebral mechanisms required for attention and concentration, such as subcortical frontal structures.

2. The term long-term memory refers to a large expanse of time that covers everything beyond short-term memory. Also known as secondary memory, it can be divided into recent (the past few weeks or months) and remote (years or decades ago). Unlike short-term memory, the capacity of long-term memory is enormous, and information can be retained in long-term memory almost indefinitely. The mesial temporal system, including the hippocampus, is required for the acquisition of knowledge into long-term memory. Other systems in the temporal lobe and elsewhere are required for the consolidation and retrieval of knowledge from long-term memory.

E. Working memory refers to a short time during which the brain can hold several pieces of information actively and perform operations on them. It is akin to short-term memory but implies a somewhat longer duration (several minutes) and more focus on the operational features of the mental process rather than simply the acquisition of information. It can be thought of as “online” processing and operating on knowledge that is being held in activated form.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

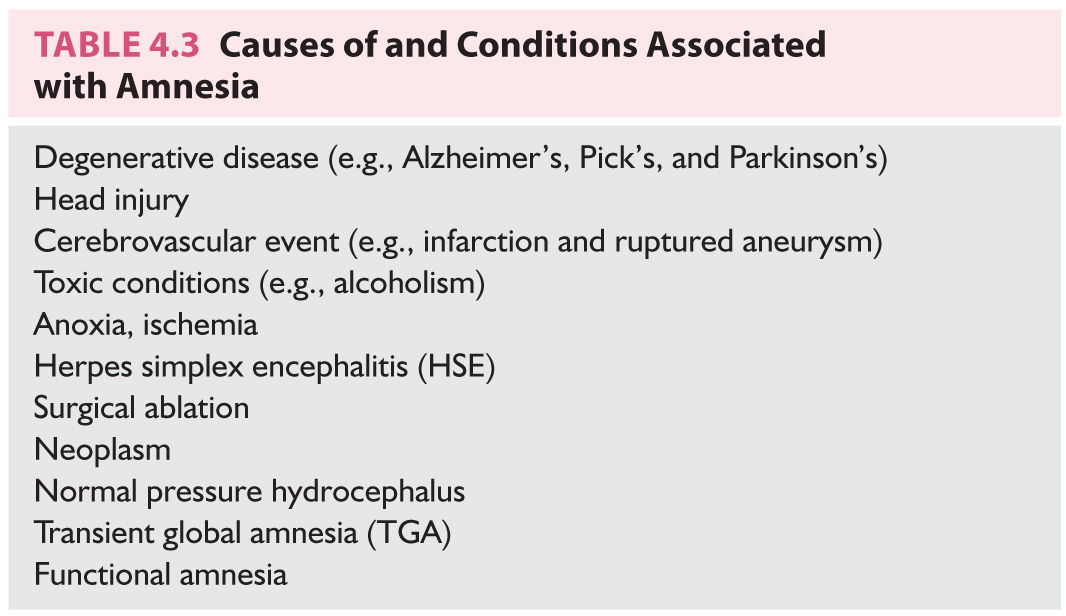

Although the etiology of cognitive impairment may differ, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), now generally classifies neurocognitive disorders as major neurocognitive disorder and mild neurocognitive disorder while retaining the term dementia as a way to describe neurodegenerative conditions (![]() Video 4.1). Associated etiology medical codes for neurocognitive disorders include AD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Lewy body disease, vascular disease, traumatic brain injury, substance/medication induced, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, prion disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease (in addition to categories that are unspecified or related to another medical condition). Several frequent neurologic conditions damage memory-related neural systems and lead to various profiles and severities of amnesia (Table 4.3).

Video 4.1). Associated etiology medical codes for neurocognitive disorders include AD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Lewy body disease, vascular disease, traumatic brain injury, substance/medication induced, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, prion disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease (in addition to categories that are unspecified or related to another medical condition). Several frequent neurologic conditions damage memory-related neural systems and lead to various profiles and severities of amnesia (Table 4.3).

Degenerative Diseases

A. Cortical dementia.

1. AD is characterized by two principal neuropathologic features—the neurofibrillary tangle and the neuritic plaque. Early in the course of the disease, the entorhinal cortex, which is a pivotal way station for input to and from the hippocampus, is disrupted by neurofibrillary tangles in cortical layers II and IV. The perforant pathway, which is the main route for entry into the hippocampal formation, is gradually and massively demyelinated. The hippocampus eventually is almost deafferentated from cortical input. AD also breaks down the efferent linkage of the hippocampus back to the cerebral cortex through destruction of the subiculum and entorhinal cortex. The hallmark behavioral sign of this destruction is amnesia—specifically, an anterograde (learning) defect that covers declarative knowledge but largely spares nondeclarative learning and retrieval. Early in the course of the disease, retrograde memory is relatively spared, but as the pathologic process extends to nonmesial temporal sectors, a defect in the retrograde compartment (retrieval impairment) appears and gradually worsens.

2. Frontotemporal dementia is characterized by symmetric atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes. The earliest and most prominent cognitive symptoms involve personality and behavioral changes. Although reports of memory problems are common in frontotemporal dementia, they are never the sole or dominating feature. Severe amnesia is considered an exclusionary criterion. Memory functioning is described as selective (e.g., “she remembers what she wants to remember”). Knowledge regarding orientation and current autobiographical events remains largely preserved.

3. Frontal lobe dementia is another form of cortical dementia. It involves focal atrophy of the frontal lobes, which causes personality changes and other signs of executive dysfunction. This condition is similar to Pick’s disease, except that there is no predominance of Pick bodies.

a. Pick’s disease, characterized by Pick bodies (cells containing degraded protein material), is an uncommon form of cortical dementia that often shows a striking predilection for one lobe of the brain, producing a state of circumscribed lobar atrophy. The disease is often concentrated in the frontal lobes, in which case personality alterations as well as compromised judgment and problem solving, rather than amnesia, are the prominent manifestations. However, the disease can affect one or the other temporal lobe and produce signs of a material-specific amnesia.

B. Subcortical dementia.

1. Parkinson’s disease is focused in subcortical structures and influences memory in a manner different from cortical forms of dementia such as AD and Pick’s disease. Disorders of nondeclarative memory (e.g., acquisition and retrieval of motor skills) are more prominent, and there may be minimal or no impairment in learning of declarative material. Patients with Parkinson’s disease often have more problems in recall of newly acquired knowledge than in storage. When cuing strategies are provided, the patients have normal levels of retention. Lewy body disease is also a neurodegenerative condition characterized by Lewy bodies that share genetic and pathologic features of both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Core features can include, but are not limited to, fluctuating cognition, hallucinations, and parkinsonism.

2. Huntington’s disease is also concentrated in subcortical structures and amnesia of patients with Huntington’s disease resembles that of patients with Parkinson’s disease. In particular, there is disproportionate involvement of nondeclarative memory. Patients with Huntington’s disease also tend to have disruption of working memory.

3. Progressive supranuclear palsy is another primarily subcortical disease process that frequently produces problems with memory. In general, however, the associated amnesia is considerably less severe than that of AD. Laboratory assessment often shows relatively mild defects in learning and retrieval despite the patient’s reports of forgetfulness.

C. Other degenerative conditions.

1. Dementia related to HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is notable for varying degrees of memory impairment, with severity being roughly proportional to disease progression. Early in the course, memory defects may be the sole signs of cognitive dysfunction. The problems center on the acquisition of new material, particularly material of the declarative type. Memory defects in this disease appear to be attributable mainly to defective attention, concentration, and overall efficiency of cognitive functioning rather than to focal dysfunction of memory-related neural systems. Various investigators have found that the rate of percentage of CD4 lymphocyte cell loss is associated with and may represent a risk factor for cognitive dysfunction among persons with HIV/AIDS.

2. Multiple sclerosis (MS) patients have varying degrees of amnesia, although the severity can wax and wane considerably in concert with other neurologic symptoms. Many patients with MS have no memory defects during some periods of the disease. When present, the memory impairment most commonly manifests as defective recall of newly learned information. Encoding and working memory are normal or near-normal. Patients with MS often benefit from cuing. The amnesia of MS usually affects declarative material of both verbal and nonverbal types; defects in nondeclarative memory are rare.

3. Head injury. Several distinct types of amnesia are associated with head injury.

a. Posttraumatic amnesia refers to the period of time following head trauma during which patients do not acquire new information in a normal and continuous manner despite being conscious. During this time, the patient may appear alert and attentive and may even deny having memory problems. It becomes apparent later that the patient was not forming ongoing records of new experiences. Information is not encoded, and no amount of cuing will uncover memories that would normally have been acquired during this period. The duration of posttraumatic amnesia is a reliable marker of the severity of head injury and constitutes one of the best predictors of outcome.

b. Retrograde amnesia is the defective recall of experiences that occurred immediately before the head injury. Information from the time closest to the point of injury is most likely to be lost. The extent of retrograde amnesia typically “shrinks” as the patient recovers, and patients are typically left with only a small island of amnesia for the few minutes or hours immediately before the trauma.

c. Learning defects (anterograde amnesia) can occur in moderate and severe head injuries when there is permanent damage to mesial temporal lobe structures, such as the hippocampus. The impairment is centered on declarative knowledge; nondeclarative learning is rarely affected. The defect may be unequal for verbal and nonverbal material if there is asymmetry of the structural injury.

4. Cerebrovascular disease.

a. Stroke is a frequent cause of amnesia, and the nature and degree of memory disturbance are direct functions of which neural structures are damaged and to what extent. Amnesia is most likely to result from infarction that damages the mesial temporal region, the basal forebrain, or the medial diencephalon, especially the thalamus.

(1) In the mesial temporal lobe, the parahippocampal gyrus and hippocampus proper can be damaged by infarction in territories supplied by branches of the middle cerebral or posterior cerebral arteries. (Strokes in the region of the anterolateral temporal lobe are uncommon.) Infarction of this type is almost always unilateral and almost always produces incomplete damage to mesial temporal memory structures; hence, the profile is one of a partial material-specific defect in anterograde memory for declarative knowledge.

(2) The most severe memory impairment results from bilateral infarcts situated in the anterior part of the thalamus in the interpeduncular profundus territory. Unilateral lesions caused by lacunar infarction in anterior thalamic nuclei produce material-specific learning defects reminiscent of those observed with mesial temporal lobe lesions. Patients with thalamic damage, however, tend to have both anterograde and retrograde defects. In the retrograde compartment, a temporal gradient to the defect is common—that is, the farther back in time one goes, the less the severity of the amnesia.

b. Ruptured aneurysms located either in the anterior communicating artery or in the anterior cerebral artery almost invariably cause infarction in the region of the basal forebrain—a set of bilateral paramidline gray nuclei that includes the septal nuclei, the diagonal band of Broca, and the substantia innominata. The amnesia associated with basal forebrain damage has several distinctive features. Patients have an inability to link correctly various aspects of memory episodes (when, where, what, and why). This problem affects both the anterograde and retrograde compartments. Confabulation is common among patients with basal forebrain amnesia. Cuing markedly improves recall and recognition of both anterograde and retrograde material.

c. Vascular dementia (VaD) refers to conditions in which repeated infarction produces widespread cognitive impairment, including amnesia. The term is used most commonly to denote multiple small strokes (lacunar strokes) in the arterioles that feed subcortical structures; hence, the usual picture is “subcortical” dementia. The memory impairment in VaD generally affects encoding of new material (anterograde amnesia), and nondeclarative learning also may be defective. Retrograde memory tends to be spared.

5. Toxic conditions.

a. Alcoholism can produce permanent damage to certain diencephalic structures, particularly the mammillary bodies and dorsomedial thalamic nucleus, which have been linked to amnesic manifestations. This presentation is known as alcoholic Korsakoff’s syndrome or Wernicke–Korsakoff’s syndrome. The amnesic profile in patients with Korsakoff’s syndrome is characterized by (1) anterograde amnesia for both verbal and nonverbal material with defects in both encoding and retrieval, (2) retrograde amnesia with a strong temporal gradient—that is, progressively milder defects as one goes farther back in time, and (3) sparing of nondeclarative memory. Confabulation is characteristic of patients with Korsakoff’s syndrome, especially in the early days following detoxification.

b. Other neurotoxins such as metals, especially lead and mercury, solvents and fuels, and pesticides, can cause amnesia from acute or chronic exposure. The relation between exposure to these substances and cognitive dysfunction is poorly understood, but there is little doubt that memory impairment often does result from excessive exposure to these neurotoxins. The amnesia tends to manifest as a deficiency in new learning (anterograde amnesia) that covers various types of materials, including verbal, nonverbal, and nondeclarative. Defects of concentration, attention, and overall cognitive efficiency are frequent contributing factors. In most cases, the memory impairment occurs in the setting of more widespread cognitive dysfunction.

6. Anoxia/ischemia, which frequently occurs in the setting of cardiopulmonary arrest, often leads to the selective destruction of cellular groups within the hippocampal formation. The extent of damage is linked to the number of minutes of arrest. Brief periods of anoxia/ischemia can cause limited damage, and longer periods produce greater destruction. With a critical length of deprivation, the damage concentrates bilaterally in the CA1 ammonic fields of the hippocampus. The result is selective anterograde amnesia affecting declarative verbal and nonverbal material. The amnesia associated with anoxia/ischemia is reminiscent of the memory defect produced by early-stage AD.

7. Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) causes a severe necrotic process in the cortical structures associated with the limbic system, some neocortical structures in the vicinity of the limbic system, and several subcortical limbic structures. The parahippocampal gyrus—particularly the entorhinal cortex in its anterior sector and the polar limbic cortex (Brodmann’s area 38)—is frequently damaged. HSE also may destroy neocortices of the anterolateral and anteroinferior regions of the temporal lobe (Brodmann’s areas 20, 21, anterior 22, and parts of 36 and 37). The destruction may be bilateral, but with the advent of early diagnosis and treatment, circumscribed unilateral damage has become more common. The profile of amnesia caused by HSE is dictated by the nature of neural destruction. Damage confined to the mesial temporal region produces anterograde declarative memory impairment. When HSE-related pathologic changes extend to nonmesial temporal structures in anterolateral and anteroinferior sectors, the amnesia involves progressively greater portions of the retrograde compartment. The retrograde defect can be quite severe if nonmesial temporal structures are extensively damaged and, in the worst case, a patient can lose almost all capacity to remember declarative information from the past and are not able to learn new information (global amnesia).

8. Surgical ablation of intractable epilepsy, especially temporal lobectomy, can result in memory impairment. Even if the resection spares most of the hippocampus proper, the resection usually involves other anterior regions of the mesial temporal lobe, including the amygdala and entorhinal cortex, resulting in mild but significant memory defects. In the most common presentation, the patient has a material-specific learning defect (nonverbal if the resection is on the right, verbal if it is on the left) after temporal lobectomy. In addition, the amnesia affects only declarative knowledge. However, mild retrograde amnesia can also result if there is sufficient involvement of the anterolateral and anteroinferior temporal sectors. Generally speaking, patients whose seizures began at an early age are less affected by temporal lobectomy than are patients whose seizures began later.

9. Neoplasms can lead to amnesia, depending on their type and location. Impaired memory is a common symptom of brain tumors, especially those centered in the region of the third ventricle (in or near the thalamus) or in the region of the ventral frontal lobes (in or near the basal forebrain). The most common therapies for high-grade malignant brain tumors, including resection and radiation, often produce memory defects. Radiation necrosis, for example, can damage the lateral portions of the temporal lobes and lead to a focal retrograde amnesia.

10. Normal pressure hydrocephalus is a partially reversible condition in which gait disturbance, incontinence, and dementia, especially memory impairment, compose a hallmark triad of presenting features. Early in the course, memory impairment can be minimal, but most patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus go on to have marked memory defects. The typical situation is anterograde amnesia for declarative material; however, problems with attention and concentration can exacerbate the amnesia and make the patient appear even more impaired than he or she actually is.

11. Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a short-lasting neurologic condition in which the patient has prominent impairment of memory in the setting of otherwise normal cognition and no other neurologic defect. The duration of TGA is typically approximately 6 or 7 hours, after which the condition spontaneously remits, and the patient returns to an entirely normal memory status. The cause of TGA is unknown, although psychological stress, vascular factors, seizure, and migraine have all been proposed as causes. During the episode, the patient has severe impairment of anterograde memory for verbal and nonverbal material. Retrograde memory is impaired to a lesser degree. After recovery, patients are unable to remember events that transpired during the episode, and sometimes a short period of time immediately before the onset of TGA also is lost. Otherwise, there is no long-term consequence.

12. Functional amnesia can occur in the absence of any demonstrable brain injury, as a consequence of severe emotional trauma, hypnotic suggestion, or psychiatric illness. These presentations have been called functional amnesia to differentiate them from amnesia caused by “organic” factors, although at the molecular and cellular levels the mechanisms may not be distinguishable. A common form is functional retrograde amnesia, in which the patient loses most or all memory of the past (including self-identity), usually after a severe emotional or psychological trauma. Curiously, anterograde memory can be entirely normal, and the patient may even have “relearning” of the past. Spontaneous recovery is frequent, although most patients are never able to remember events that transpired during the episodes in which they had amnesia. Another interesting form is posthypnotic amnesia, the phenomenon whereby patients cannot remember events that transpired while they were under hypnosis.

EVALUATION

A. History.

1. Onset. Through careful history-taking, the clinician should determine as precisely as possible the timing of the onset of the problem. Memory defects that began years ago and have gradually worsened over time point to degenerative disease, such as AD. Reports of sudden memory impairment among younger patients, for whom psychological factors (e.g., severe stress and depression) can be identified as being temporally related to the problem, should raise the question of nonorganic etiologic factors.

2. Course. The history-taking should document carefully the course of the concern. Progressive deterioration in memory signals a degenerative process. Memory defects after head injury or cerebral anoxia, by contrast, tend to resolve gradually, and reports to the contrary raise the question of other (psychological) factors.

3. Nature. The clinician should explore the nature of the problem. With what types of information, and in what situations, is the patient having trouble? Patients may produce vague, poorly specified concerns (e.g., “My memory is bad” or “I’m forgetful”), and it is important to request specific examples to form an idea as to the actual nature of the problem. Patients tend to use the term “memory impairment” to cover a wide range of mental status abnormalities, and, again, elicitation of examples is informative. Patients who say they “can’t remember” may actually have circumscribed impairment of word finding, proper name retrieval, or hearing or vision.

B. Bedside examination. Memory assessment is covered to some extent by almost all bedside or screening mental status examinations. If patients pass such examinations, do not report memory impairment, and are not described by spouses or caretakers as having memory difficulties, it is safe to assume that memory is broadly normal. If any of these conditions are not met, a more complete evaluation of memory is warranted. Referral for neuropsychological assessment provides the most direct access to such evaluation.

1. Learning. Can the patient learn the examiner’s name? Three words? Three objects?

2. Working memory. Backward spelling, serial subtraction, and repeating numerical strings of digits backward are good probes of working memory.

3. Delayed recall. It is important to ask for the retrieval of newly acquired knowledge after a delay, for example, approximately 30 minutes. This may reveal a severe loss of information on the part of a patient who performed perfectly in an immediate recall procedure.

4. Retrograde memory. The patient should be asked to retrieve knowledge from the past. This should be corroborated by a spouse or other collateral person, because patients with memory defects may confabulate and otherwise mislead the examiner.

5. Orientation. The patient should be asked for information about time, place, and personal facts. Defects in orientation are often early clues to memory impairment.

6. Attention. Marked impairment of attention produces subsequent defects on most tests of memory. The diagnosis of amnesia, however, should be reserved for patients who have normal attention but still cannot perform normally on memory tests. Attentional impairment per se is a hallmark of other abnormalities, not necessarily of an amnesic condition.

C. Laboratory studies of memory are conducted in the context of neuropsychological assessment, which provides precise, standardized quantification of various memory capacities. Examples of some widely used procedures are as follows.

1. Anterograde memory. Most conventional neuropsychological tests of memory, including the Wechsler Memory Scale, fourth edition (WMS-IV), and other such instruments, assess learning of declarative knowledge. It should not be assumed that all aspects of memory are normal simply because the patient passes these procedures. For example, these tests do not measure nondeclarative memory, and they rarely provide adequate investigation of the retrograde compartment. Nonetheless, the WMS-IV and related procedures provide sensitive, standardized means of quantifying many aspects of memory.

a. Verbal. In addition to several verbal memory procedures that comprise part of the WMS-IV (e.g., paragraph recall and paired-associate learning), there are several well-standardized list-learning procedures in which the patient attempts to learn and remember a list of words. The Rey Auditory–Verbal Learning Test, for example, requires the patient to learn a list of 15 words. Five successive trials are administered, and then a delayed recall procedure is performed after about 30 minutes. The patient’s learning capacity, learning curve, and the degree of forgetting can be determined.

b. Nonverbal memory tests typically involve administration of various designs, such as geometric figures, that the patient must remember (e.g., WMS-IV Visual Reproduction and the Benton Visual Retention Test). Face-learning procedures also provide good tests of nonverbal memory.

2. Retrograde memory. There are several standardized procedures for measuring retrograde memory, including the Remote Memory Battery, the Famous Events Test, and the Autobiographical Memory Questionnaire. These procedures probe recall and recognition of various historical facts, famous events and persons, and autobiographical knowledge. Corroboration of retrograde memory, particularly with regard to autobiographical information, is extremely important to determine the severity of retrograde memory defects.

3. Nondeclarative memory. A standard procedure for measuring nondeclarative learning is the Rotary Pursuit Task, which requires the patient to hold a stylus in one hand and attempt to maintain contact between the stylus and a small metal target while the target is rotating on a platter. Successive trials are administered and are followed by a delay trial. This procedure allows the measurement of acquisition and retention of the motor skill.

4. Working memory. The Digit Span Backward and Sequencing subtests from the WAIS-IV, as well as the Letter–Number Sequencing and Arithmetic subtests, provide a sensitive means of quantifying working memory. In Letter–Number Sequencing, the patient is read a combination of numbers and letters of varying lengths and is asked to repeat them by first stating the numbers in ascending order and then the letters in alphabetical order. In Arithmetic, patients must mentally solve math problems. The Trail-Making Test, which requires the patient to execute a psychomotor response while tracking dual lines of information, is also a good probe of working memory. Another commonly used procedure is the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, in which the patient must add numbers in an unusual format under increasingly demanding time constraints. Finally, the Spatial Span subtest from a previous version of the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-III) is the visual–spatial analog of the aforementioned auditory–verbal subtest, Digit Span. Rather than recalling numbers in forward and backward order, spatial span requires the examinee to replicate, forward and backward, an increasingly long series of visually presented spatial locations.

5. Long-term memory. The ability to acquire new information, in addition to consolidate and store that information and retrieve it at a later time, is the real crux of memory. In a practical sense, it is not very helpful to have normal short-term memory if one cannot transfer the information into a more permanent storage area. Hence, delayed recall and recognition procedures, which yield information about the status of long-term memory, are very important in memory assessment and can also provide information regarding the etiology of memory impairments.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Different causes of amnesia have different implications for diagnosis and management. The following common differential diagnoses are particularly challenging.

A. Normal aging. A seemingly minor but practically difficult challenge is to differentiate true memory impairment from the influences of normal aging. Aging produces certain declines in memory, which can be misinterpreted by patients and clinicians alike as signs of neurologic disease. Many older adults who report “forgetfulness” turn out to have peer-equivalent performances on all manner of standard memory tests, and the diagnosis of amnesia is not applicable. Patients may be quick to interpret any episode of memory failure as a sign of AD, or they may adamantly deny memory dysfunction in the face of obvious real-world impairment. Consequently, careful quantification of the memory profile aids in the differential diagnosis.

B. Psychiatric disease. Many psychiatric diseases produce some degree of memory impairment. Accurate diagnosis is critical, because most memory defects caused by psychiatric disease are reversible, unlike most of amnesia that occurs in the setting of neurologic disease.

1. Dementia related to depression (sometimes called pseudodementia) is a condition that produces memory impairment and other cognitive defects resembling “dementia” but not caused by neurologic disease. Severe depression is the typical cause. Patients with pseudodementia often have memory impairment such as anterograde amnesia that is quite similar to that in the early stages of degenerative dementia. However, depressed patients respond to treatment with antidepressant medications and psychotherapy; when the affective disorder lifts, memory returns to normal.

2. Depression is a common cause of memory impairment among all age groups. Distinguishing features, however, help differentiate amnesia due to depression from amnesia caused by neurologic disease. Depressed patients tend to have problems in concentration and attention, and they may have defects in working memory and other short-term memory tasks. Long-term memory is less affected, and retrograde memory is normal. Apathetic, “don’t know” responses are common among depressed patients, whereas patients with a neurologic disorder more often give incorrect, off-target responses. Depressed patients also tend to describe their memory problems in great detail, whereas patients with a neurologic disorder, such as those with suspected Alzheimer’s dementia, generally discount memory problems. Patient history is informative and the clinician can usually find evidence of major stress, catastrophe, or other circumstances, and it is apparent that the onset of the memory problems coincided with the onset of the affective disorder.

3. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder can also cause memory impairments among all age groups. Similar to depression, individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder often demonstrate difficulties with attention and concentration that affect learning or encoding (e.g., frontal lobe systems disruption). That is, it is difficult to have memory for an item not learned. Such individuals might have less difficulty retrieving what they have learned and might also be able to cue up or recognize items more readily than an individual who might have a neurologic condition.

C. Side effects of medications. Many medications commonly prescribed for older adults produce adverse side effects on cognitive function, including memory. It is important to know what medications a patient has been taking and to account for the extent to which those medications may be causing memory impairment. The history often reveals that the onset of memory problems coincided with or soon followed the beginning of use of a particular medication. Memory defects caused by medication side effects also tend to be variable—for example, worse at certain times of the day. The main problems concern attention, concentration, and overall cognitive efficiency; memory defects are secondary.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

The diagnostic approach to a patient with amnesia should include any procedures necessary for establishing both the most likely cause and the precise nature of the memory impairment. The most commonly used procedures are as follows.

A. Neurologic examination should establish whether a memory problem is present, the general degree of severity, and the history of the problem. It is not uncommon for patients with amnesia to underestimate or even deny the problem; information from a spouse or caretaker is a critical part of the history. Careful mental status testing can provide sufficient characterization of the amnesia profile.

B. Neuroimaging procedures, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), are almost always helpful in diagnosing the cause of amnesia. Functional imaging, such as positron emission tomography, may demonstrate abnormalities suggestive of AD (e.g., bilateral parietotemporal hypometabolism) earlier in the natural course of the disease than may MRI, CT, or clinical assessment.

C. Neuropsychological assessment provides detailed quantification of the nature and extent of memory impairment. Such testing should be considered for almost all patients with amnesia, although there may be instances in which the mental-status-testing portion of the neurologic examination provides sufficient information.

CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of amnesia is appropriate whenever there are memory defects that exceed those expected given the patient’s age and background. Some conditions, such as severe aphasia, make it difficult to assess memory in a meaningful way. Amnesia should not be diagnosed if the patient is in a severe confusional state, in which attentional impairment rather than memory dysfunction is the principal manifestation (e.g., delirium). Otherwise, amnesia can occur in isolation or coexist with almost any other form of impairment of mental status. It is customary to regard patients as having amnesia if there is considerable discrepancy between the level of intellectual function and one or more memory functions. There are many different subtypes of amnesia. Diagnosis of such subtypes usually requires fine-grained quantification, such as that provided in a neuropsychological laboratory.

REFERRAL

A. Neuropsychological evaluation is appropriate for almost all patients with manifestations of amnesia. The following situations that occur commonly in clinical practice particularly call for such a referral.

1. Precise characterization of memory capacities. For a patient who has sustained brain injury, neuropsychological assessment provides detailed information regarding the strengths and weaknesses of the patient’s memory. In most instances, memory assessment should be performed as early as possible in the recovery period. This evaluation provides a baseline to which recovery can be compared. Follow-up assessments assist in monitoring recovery, determining the effects of therapy, and making long-range decisions regarding educational and vocational rehabilitation.

2. Monitoring the status of patients who have undergone medical or surgical intervention. Serial neuropsychological assessment of memory is used to track the course of patients who are undergoing medical or surgical treatment for neurologic disease. Typical examples include drug treatment for patients with Parkinson’s disease, seizure disorder, surgical intervention for patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus, or a brain tumor. Neuropsychological assessment provides a baseline memory profile with which changes can be compared and provides a sensitive means of monitoring changes in memory that occur in relation to particular treatment regimens.

3. Differentiating neurologic and neuropsychiatric disease. Neuropsychological assessment can provide evidence crucial to the distinction between amnesic conditions that are primarily or exclusively neurologic and those that are primarily or exclusively neuropsychiatric. A common diagnostic dilemma faced by neurologists and psychiatrists is differentiating “true dementia” (e.g., cognitive impairment caused by AD) and “pseudodementia” (e.g., cognitive impairment associated with depression).

4. Medicolegal situations. Cases in which “brain injury” and “memory impairment” are claimed as damages by plaintiffs who allegedly have sustained minor head injuries or have been exposed to toxic chemicals. In particular, there are many cases in which hard or objective signs of brain dysfunction (e.g., weakness, sensory loss and impaired balance) are absent, neuroimaging and electroencephalogram (EEG) findings are normal, and the entire case rests on claims of cognitive deficiencies, particularly memory dysfunction. Neuropsychological assessment is crucial to the evaluation of such claims.

5. Conditions in which known or suspected neurologic disease is not detected with conventional neurodiagnostic procedures. There are situations in which the findings of standard diagnostic procedures, including neurologic examination, neuroimaging, and EEG, are equivocal, even though the history indicates that brain disease and amnesia are likely. Examples include the early stages of degenerative dementia syndromes and early HIV-related dementia. Neuropsychological assessment in such cases provides the most sensitive means of evaluating memory.

6. Monitoring changes in cognitive function over time. In degenerative dementia in particular, equivocal findings in the initial diagnostic evaluation are not uncommon. In such cases, follow-up neuropsychological evaluation can provide important confirming or disconfirming evidence regarding the status of the patient’s memory and possible progression of a disease process.

B. Rehabilitation. Another common application of neuropsychological assessment is the case in which a patient undergoes cognitive rehabilitation for amnesia. Neuropsychological data collected at the initial assessment can help determine how to orient the rehabilitation effort. Subsequent examinations can be used to measure progress during therapy.

Key Points

• There are several different types of memory that must be understood in order to identify neuroanatomical correlates. As examples, working memory involves the frontal lobe while anterograde and declarative memory involves the mesial temporal lobes.

• The etiology of memory impairments can differ, so it is important to always identify specific memory problems, as well as the onset and course of the memory impairments.

• Some common causes of memory impairment can be attributable to neurodegenerative diseases, such as cortical (e.g., AD) and subcortical disease (e.g., Parkinson’s disease), as well as other neurodegenerative conditions (e.g., MS), head injury, cerebrovascular and psychiatric disease.

• A neuropsychological evaluation is especially useful to objectively quantify memory impairments and the nature of the impairments, including anterograde memory, verbal memory, nonverbal memory, retrograde memory, nondeclarative memory, working memory, and long-term memory.

• Neuropsychological evaluations are appropriate for almost all patients with memory complaints to characterize the memory impairments in addition to providing information about monitoring and outcomes, aid in differential diagnosis, and provide recommendations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree