Fig. 31.1

Intraparenchymal hematoma related to aspirin and Plavix. Axial (a) and coronal (b) non-contrast CT images show a large right cerebral hemisphere hematoma with associated midline shift to the left and obstructive hydrocephalus

A rare, but devastating complication of aspirin use is Reye syndrome, which consists of hepatitis and encephalopathy in the setting of a viral illness, particularly in the pediatric population. On imaging, diffuse cerebral edema and signal alterations in brainstem, bilateral thalami, medial temporal lobes, parasagittal cortex, and cerebellar and subcortical white matter are evident. In addition, there can be diffusion restriction in the thalami, midbrain, cerebellar white matter, subcortical white matter, and watershed territories. The imaging abnormalities tend to resolve as the patients recover from this condition.

An additional complication of aspirin use that may be encountered on neuroimaging is nasal polyposis in patients with aspirin sensitivity and asthma (Samter’s triad). Non-contrast CT of the sinuses often shows widespread mucosal inflammation and bilateral polypoid opacities in the sinonasal cavities (Fig. 31.2). Patients with Samter’s triad tend to have a more extensive sinonasal disease and a higher rate of nasal polyp recurrence following endoscopic sinus surgery than aspirin-tolerant patients. Patients with aspirin sensitivity may also develop aural polyps.

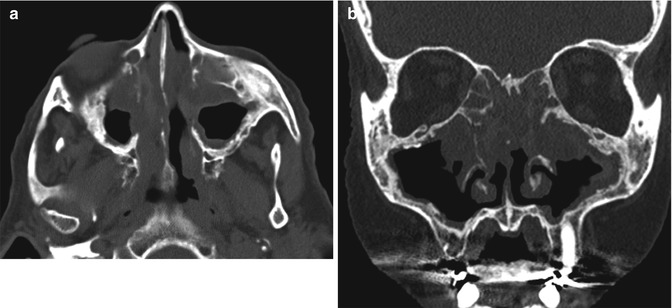

Fig. 31.2

Nasal polyps in aspirin sensitivity syndrome. Axial (a) and coronal (b) non-contrast CT images show extensive, bilateral sinonasal opacification related to multiple polypoid soft tissue densities in a patient with prior endoscopic sinus surgery

31.4 Differential Diagnosis

Differential considerations for acute, nontraumatic cerebral hemorrhage include hypertensive hemorrhage, with characteristic locations in the basal ganglia, thalamus, pons, and cerebellum; amyloid angiopathy, which classically demonstrates a lobar distribution and associated foci of blooming or “black dots” on SWI in a subcortical distribution (Fig. 31.3); vascular malformations (Fig. 31.4); venous sinus thrombosis (refer to Chaps. 20 and 47); cocaine or alcohol abuse (refer to Chaps. 2 and 5); primary CNS vasculitis (refer to Chaps. 5, 6, and 10); hemorrhagic neoplasm, for which tumoral enhancement may be minimal; and hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic stroke. The imaging interpreter must combine imaging findings with clinical history, including age of the patient, medical comorbidities, and medication use, in order to arrive at the most probable diagnosis. In patients without a clear etiology of the intracranial hemorrhage on initial evaluation, CTA or MRA should be recommended. Furthermore, underlying lesions may not be apparent in the acute phase of hemorrhage, and follow-up imaging in 2–3 months is often warranted (Fig. 31.5).

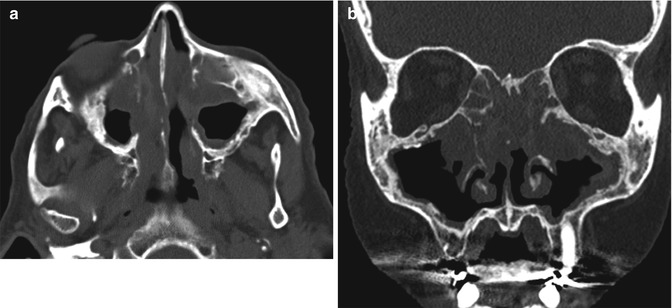

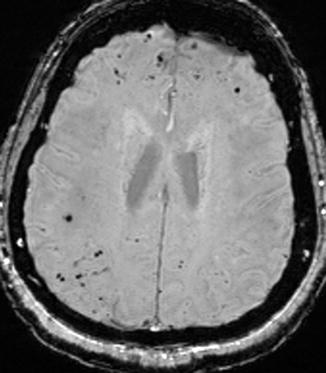

Fig. 31.3

Amyloid angiopathy. Axial SWI image demonstrates numerous subcortical punctate foci of susceptibility effect consistent with foci of chronic microhemorrhage

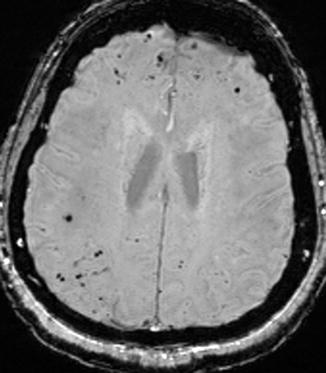

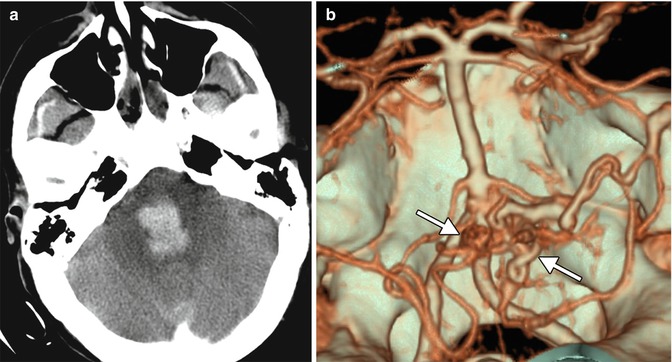

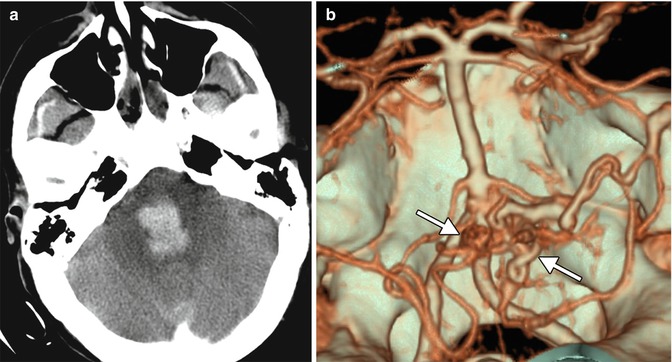

Fig. 31.4

Ruptured arteriovenous malformation. Axial non-contrast CT image (a) shows an acute hematoma within the pons and fourth ventricle. 3D CTA image (b) shows the vascular nidus of an arteriovenous malformation arising from the vertebrobasilar circulation (arrows)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree