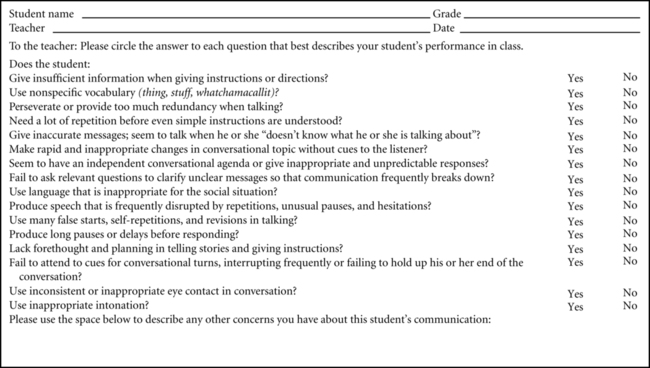

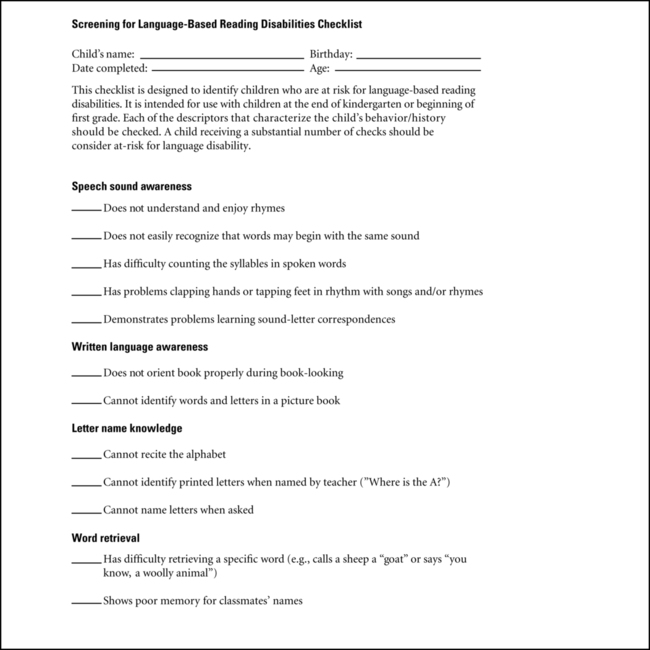

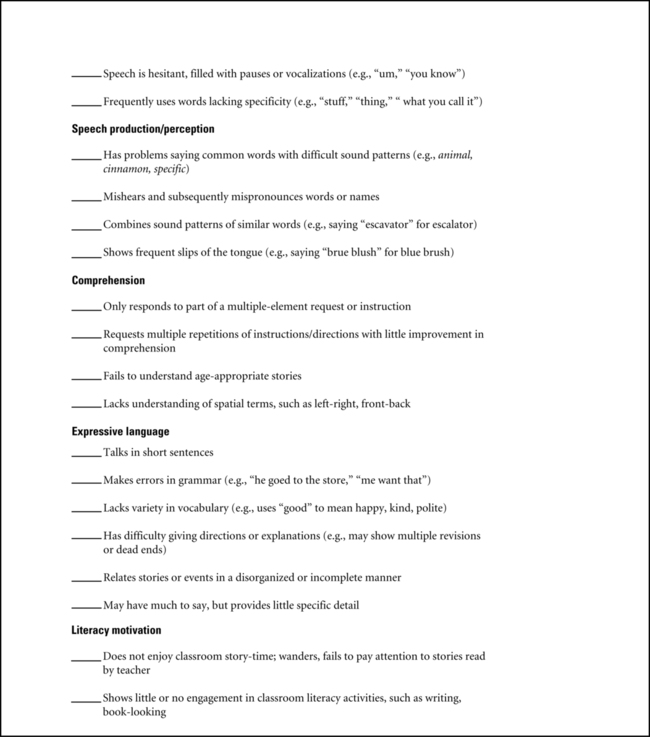

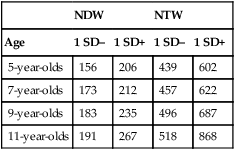

Chapter 11 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Describe how families participate in educational planning for school-aged children. 2. Discuss the role of responsiveness to intervention (RTI) in identifying students for communication assessment. 3. Define and describe methods for screening at the elementary school level. 4. Discuss methods of referral and case-finding. 5. Discuss the uses of standardized tests at the elementary school level. 6. Describe nonstandardized assessment methods for students in elementary grades. 7. Carry out language analysis procedures for conversation and narratives. 8. Use dynamic and curriculum-based assessment methods. 9. Apply concepts discussed to assessment of students with severe disabilities. When we, as speech-language pathologists (SLPs), assess students like Nick and Maria, we want to bear in mind the issues we discussed in Chapter 10 about the need to look not only at basic oral language skills but also at the specialized abilities that contribute to success in the classroom in general and in reading in particular. In this chapter, we’ll talk about assessment issues for students who are beyond the developing language phase, with skills above Brown’s stage V. We will focus on children who have mastered the basic vocabulary, sentence structures, and functions of their language but have trouble progressing beyond these basic skills to higher levels of language performance. This chapter and Chapter 12 focus specifically on clients whose developmental levels are commensurate with those of students in the elementary grades. We will be talking about the communicative skills needed for the elementary school years, from kindergarten through fifth or sixth grade when typical children are between 5 and 12 years of age. Of course, some children at these chronological age levels who are served in schools function at lower levels. Particularly with the push toward inclusion of students with disabilities embodied in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), clinicians find students in elementary schools who function at the developing, emerging, or even prelinguistic stages of communication. When these students are included in the caseload of a school SLP, assessment and intervention strategies appropriate for their level of functioning are needed. Information on assessment and intervention strategies for students at these levels of development can be found in Section II. Although the stage of development we’re considering in these chapters usually takes place when children are between 5 and 12 years of age, we may encounter some clients with language-learning disabilities in middle school or even high school who function at this elementary grade level. For these students and for their younger counterparts, the assessment and intervention information presented in this chapter and Chapter 12 is germane. Let’s call this phase of language development the “language for learning” period (L4L for short). The L4L stage is when many of the oral language bases for school success, including the knowledge of special classroom-discourse rules, decontextualized language, metalinguistic and phonological awareness, and literacy skills that we talked about in Chapter 10 must be acquired in order for the student to meet the demands of the curriculum. Although IDEA legislation mandates that families be involved in the assessment and intervention process for students with special educational needs, this ideal is not always fully met in practice. Parents may not know that their child has been having difficulty until they are told a referral has been made. Because the assessment often takes place at school, the parent may not have an opportunity to observe it and contribute a family perspective. Clinicians particularly committed to curriculum-based assessment (e.g., Jenkins, Graff, & Miglioretti, 2009; Nelson & Van Meter, 2002; Nelson, 2010) may feel that the teacher has more relevant information to contribute about the student’s needs than the family does. However, the principles of family-centered practice are just as relevant for children in the L4L stage as they are for younger clients. These principles remind us that families need to be involved in each stage of the assessment process, from referral to remedial planning. This means contacting parents as soon as a referral is made, discussing the referral, and learning whether the family shares the referring person’s perceptions about the student. A telephone conference can often be beneficial at this stage, using the same communication strategies as those outlined in Chapter 7 for parent contacts. Parental permission for the assessment must be obtained, and parents should be invited to attend any assessment sessions they wish. Parents should be kept informed periodically of the progress of the assessment, if it stretches over a period of time, and should be invited to attend a meeting when the assessment is complete to discuss the evaluation with the team and to provide input in the development of an Individual Educational Plan (IEP). One way children make their way to the school SLP is through screenings. These are often conducted upon entrance into the school system for the first time, or at particular grade levels. This sometimes includes screening for hearing, as well. Some school systems use mass screenings in which all children beginning kindergarten are screened during a few designated periods by professionals or paraprofessionals using short standardized instruments, such as the Fluharty Preschool Speech and Language Screening Test—2nd Edition (Fluharty, 2000), the Joliet 3-Minute Speech and Language Screen—Revised (Kinzler & Johnson, 1993), or Developmental Indicators for the Assessment of Learning—3rd Edition (Mardell & Goldenberg, 1998). Some districts use locally developed, informal methods. Other local educational agencies (LEAs) set aside the first week or two of kindergarten for individual screenings. Each new student meets with a teacher or team for a somewhat more intensive screening. These screenings have several possible outcomes. A recommendation to wait a year before entering kindergarten may be given, to let the child mature. Alternatively, students may be placed in a developmental kindergarten program for some preschool-level instruction with the expectation that they will enter regular kindergarten the next year. Screening also can lead to a referral for an assessment in greater depth in one area, such as communication, or by a multidisciplinary team. SLPs often participate in these screenings and may identify children who will join their caseload as a result. Finally, some schools use a responsiveness to intervention (RTI) approach to identify children with difficulties (see Chapters 3 and 10 for details). Whether the SLP participates directly in screenings or not, it is our responsibility to interpret screening information and contribute to decisions about which children need further assessment. Many school districts use informal, locally developed methods for screening, particularly for mass kindergarten screenings. Although this practice is widespread, it is not, we would argue, advisable. A screening instrument should have well-documented psychometric properties, because that is the best way to ensure its fairness. Some critics of kindergarten screening have argued that early identification through screening is unfair to minorities, culturally and linguistically different (CLD) children, and those from low-income families (Braddock & McPartland, 1990; Pavri & Fowler, 2001). Although many of these arguments may apply to standardized as well as informal procedures, the issue of unfairness is much more pronounced when screening is done using intuitive or subjective criteria. Using nationally standardized norms, norms developed and tested locally with a relatively large normative sample, or measures that provide evidence of reliability and validity and include children from a range of ethnic and economic backgrounds helps us to guarantee that screening procedures are as fair as we can make them. One example is presented by Massa, Gomes, Tartter, Wolfson, & Halperin (2008), who used the Observational Rating Scale from the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-3 (Semel et al., 1995) completed by parents and teachers to screen 7- to 10-year-old children for difficulties in listening, speaking, reading and writing in a culturally diverse urban setting. Results revealed that the general questions posed on this measure (such as “Does you child have trouble with spoken directions?’) showed reliability and validity for both parent and teacher responses in identifying language disorders in this population. In addition to demonstrated reliability and validity and a large and representative norming sample, a screening test should have some additional properties. It should cover a relatively wide range of language behaviors, provide clear scoring with pass/fail criteria, have adequate sensitivity and specificity to accurately identify a large majority of children who have language difficulties, and take a short amount of time (Justice, Invernizzi, & Meier, 2002; Sturner et al., 1994). The only way to find out whether a test meets these standards is to read the manual carefully. We need to look at the norming sample to see whether it contains children such as those on whom we will be using the test. We need to review the items to evaluate their comprehensiveness. We need to look at the scores and statistics provided to determine whether the test is valid and reliable, provides adequate sensitivity and specificity (see Chapter 2), and gives a usable pass/fail standard. We need to try it a few times to see whether it is efficient to use. When we find a test that meets these standards, we can feel confident that our screening will be fair, efficient, and accurate. Some instruments that have been developed for screening communicative skills in school-age children are listed in Appendix 11-1. Still, the availability of psychometrically sound instruments is a problem. Sturner et al. (1994) found in their review of 51 standardized screening instruments that only six provided adequate validity data. Only nine were found to be adequately brief and comprehensive. Justice, et al. (2002) report that none of the six early literacy screening instruments they examined contained all essential features. Spaulding, Plante, and Farinella (2006) reported that information on test sensitivity and specificity, which would help clinicians decide how accurately the test identifies children with language disorders, was available for only 20% of the language tests they evaluated, and acceptable accuracy (80% or better) was reported for only 12%. These findings underline the importance of being critical consumers in selecting commercial tests and screening instruments. Just because a test is published does not mean it has adequate psychometric properties. We need to review the tests we use carefully to ensure they are fair, efficient, and effective. Moreover, we should argue for careful consideration of psychometric properties in the selection of any screening instruments our schools use. This can help to ensure that we provide assessment services in a fair and appropriate way. Another way to optimize the efficacy of teacher referrals, particularly in schools or grade levels where RTI is not being used, is to provide teachers with specific criteria or checklists to use. We can distribute these checklists to classroom teachers and ask them to fill out one for each student in the class who seems to be having difficulty or about whom they have some concern. Damico and Oller (1980) found that encouraging teachers to use pragmatic criteria for referral, rather than criteria based on syntactic and morphological errors, resulted in more accurate referrals. Damico (1985) developed a Clinical Discourse Analysis Worksheet to analyze a speech sample of students with language-learning disorders (LLDs). This worksheet can be modified and used as a pragmatically oriented checklist to be given to teachers as a basis for referring students. One such modification appears in Figure 11-1. Any student for whom a teacher answers “yes” to several (more than four, say) of these questions could be a candidate for assessment in greater depth. Once we identify these students, of course, we can assess them in a variety of areas, including but not limited to pragmatics. Pragmatic criteria for referral, though, seem to be a valid way to identify which students are having problems with the linguistic demands of the classroom. Bishop (2003) developed the Children’s Communication Checklist—2 (CCC-2), in order to identify students with specific language disorders and to differentiate problems in language form from those in the area of pragmatics. Botting (2004) showed that the CCC-2 is sensitive to children with a variety of communication impairments. The CCC-2 can also serve as tool to help teachers make referrals for students with communication difficulties (Appendix 11-2). The Pragmatic Language Skills Inventory (Gilliam & Miller, 2006) is also a useful tool. Additional suggestions for using checklists to identify children in primary grades who may be at risk for literacy problems come from Catts (1997) and Justice et al. (2002). A checklist based on their suggestions is shown in Figure 11-2, which can be used to help first-grade teachers identify students who may have LLD, and can be used as part of the monitoring system for tracking progress of children in RTI classrooms. In addition to identifying students with language disorders within the general education population who may not have been previously identified, SLPs in RTI settings also play a role in monitoring progress across the RTI Tiers. As we’ve seen, in RTI settings, students will be provided with scientifically based literacy instruction in general education at Tier I, and those who experience significant difficulties will receive more intensive, small group instruction at Tier II. Monitoring of progress within these tiers may include commercial reading assessments (Mellard, McKnight, & Woods, 2009), benchmark measures such as the Phonological Awareness and Literacy Screening (PALS; Invernizzi & Meier, 2002) to evaluate classroom performance as a whole on specific high-priority reading targets (Justice, 2006), or curriculum-based methods such as the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS; Kaminski & Good, 1998) to evaluate performance on specific indicators of progress within the curriculum. Benchmark measures will usually be administered several times during the school year to track progress of the class as a whole and identify students who fail to achieve predetermined standards. Curriculum-based assessments are typically used more frequently, as often as weekly, to identify children who are not acquiring the specific skills being presented in the curriculum. According to Justice (2006), the benchmark measures differ from curriculum-based measures in that benchmark measures can be used to identify goals for future instruction, such as increasing the number of letter-sound associations known. This level of monitoring is analogous to what SLPs do when we assess children’s current level of performance in oral language, and use the information collected to plan an intervention program. Curriculum-based assessments, on the other hand, are often timed and are designed to be quick (“How many letters can a child name in 1 minute?”). Instead of translating directly into instructional goals, these measures are used to track progress over time, and to show that particular children have a slower rate of growth than their peers. They are similar to the probes an SLP might present within an ongoing intervention program to learn whether or not the child is progressing. Figure 11-3 shows an example of curriculum-based assessment; here, progress monitoring of the number of words read from a standard word list in a first grade classroom shows that Students 10, 11, and 12 are making much slower gains on this measure over the course of the Fall term than their peers. It is this slowed rate of growth that would lead to placement for these children in a Tier II group. Additional information and materials for progress monitoring are available at the National Center on Student Progress Monitoring Web site: www.rti4success.org/chart/progressMonitoring/progressmonitoringtoolschart.htm#. Once Tier II intervention is initiated, progress would be monitored just as it was in Tier I, using both benchmark and curriculum-based methods. Tier II intervention itself is, in a way, a kind of dynamic assessment (see Chapter 2), in which we provide some diagnostic teaching to determine whether it is sufficient to overcome a child’s difficulty. If so, the child may move back into Tier I and be monitored there. Occasional “doses” of Tier II intervention may be sufficient to allow some children to develop proficient reading skills. School-based clinicians will probably find that some standardized testing is needed in the L4L stage. The reason can be summed up in one word: eligibility. Many states require that a student perform below a designated level on some standardized measure to qualify for special educational services, including the services of the SLP. States have differing criteria for eligibility for various kinds of speech-language services, but most include a requirement for some standardized testing. Moore-Brown and Montgomery (2005), for example, give examples of the variety of eligibility criteria used in various states within the United States. These include levels of performance on standardized tests, severity ratings, general indicators of delay, and results of the RTI process. At least one-third of the states reviewed require some form of standardized testing to establish eligibility. When a student has been referred by a teacher or identified as having language deficits as a result of a screening, a first step is often to establish the student’s eligibility for services by means of standardized testing. Appendix 11-2 provides a sample of standardized tests developed for students in the L4L period. If a pragmatically oriented checklist has been used as a referral tool, the clinician may not have much sense of what the student’s performance in language form and content might be. To begin to get such a sense, a short conversational interaction, such as the one we talked about for assessing intelligibility for children with developing language in Chapter 8, can be used. By talking to the student informally for a brief time (say 5 minutes), an SLP can break the ice and give both participants a chance to get to know each other a little. The SLP also can get a feel for what the child’s linguistic abilities and disabilities might be. This brief conversational sample can help point us toward the assessment instruments that will help establish the student’s eligibility for services. Comprehensive batteries are commonly used in the assessment of students with LLD. Most states allow children to qualify for services if they score below a certain level on some subtests of a standardized battery or if they score below criterion on one subtest of a similar area on two standardized batteries. In these cases, batteries that look at a broad spectrum of abilities will be most useful in identifying students, like many of our clients with LLD, who perform adequately in some aspects of language but have difficulty in a few areas that are interfering with their achievement in school. Some examples of test batteries that can be used in this way include Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—4 (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003; which also contains a checklist for assessing pragmatics), Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999b), Test of Language Development—3—Primary and Intermediate (Newcomer & Hammill, 1997), and the Utah Test of Language Development—4 (Mecham, 2003). These batteries can sample a range of oral language abilities, in the hope of identifying specific areas in which students are having problems that will qualify them for services, as well as pointing out areas of strength. As we saw in Chapter 10, students with LLD commonly have pragmatic deficits, and some have their primary deficits in this area. Standardized tests of pragmatics, then, can be useful for establishing eligibility. As we discussed earlier, using a standardized test to assess pragmatic function is something like using a sound-level meter to assess the quality of a symphony. Since pragmatic function is the ability to use language appropriately in real conversation, its assessment in a formal setting is bound to be somewhat limited and artificial. Tests of pragmatics may not be a necessary part of the assessment battery for children at earlier language levels, who will have plenty of deficits in form and content. Still, these tests can be useful for documenting deficits at the L4L stage, when children have outgrown some of the more obvious form and content problems. Standardized tests of pragmatics in students with LLD most likely will be used to establish eligibility for services. Some students with LLD, as well as high-functioning students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) will not score low enough on tests of language form and content to qualify for communication intervention. Using a test of pragmatics with these clients may provide information that substantiates our informal assessment of their deficits in pragmatic areas. In other words, we can use standardized tests of pragmatics for the basic purpose for which all standardized tests were designed: to show that a child is different from other children. A few examples of standardized tests in this area include the Test of Pragmatic Language (Phelps-Terasaki & Phelps-Gunn, 1992), the Communication Abilities Diagnostic Test (Johnston & Johnston, 1999), and Test of Language Competence Expanded Edition (Wiig & Secord, 1989). Recently, Young, Diehl, Morris, Hyman, and Bennetto (2005) showed that the Test of Pragmatic Language was helpful in identifying pragmatic deficits in students with autism spectrum disorder. Reichow et al. (2008) showed how subtests of the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (Woolfolk, 1999) can also be used in this way. The Children’s Communication Checklist 2, (Baird, 2003), too, has been shown to be useful for this purpose. A third type of standardized test also can help assess students that the clinician believes need help with oral language foundations for the classroom. These tests look specifically at learning-related language skills. Some examples of these kinds of tests are the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (Wagner, Torgenson, & Rashotte, 1999), the Language Processing Test—3 (Richard & Hanner, 2005), the Test of Awareness of Language Segments (Sawyer, 1987), the Test of Early Written Language—2 (Herron, Hresko, & Peak, 1996), the Test of Relational Concepts-Revised (Edmonston & Thane, 1999), the Test of Word Finding in Discourse (German, 1991), and the Word Test—2—Revised (Huisingh, Bowers, LoGuidice, & Orman, 2004). These tests specifically tap the language skills that are likely to be less developed in students with LLD. Tests such as these are likely to show that a student with LLD is significantly different from peers in areas of language skills that influence academic performance and can be used to help establish eligibility for services. Most students with LLD who function at the L4L stage do not make a large number of phonological errors. Some distort a few sounds or retain one or two phonological simplification processes. When this is the case, procedures discussed for the developing language stage can be used to assess these problems. If obvious phonological errors are not evident, though, we may want to know how phonologically “robust” the child’s system is. As we’ve discussed, researchers such as Catts (1986); Dollaghan and Campbell (1998); and Graf Estes, Evans, and Else-Quest (2007) have shown that children with LLD often have trouble with phonologically demanding tasks, such as producing complex, unfamiliar words and phrases, even when their conversational speech is not full of errors. Such vulnerability may indicate problems with phonological awareness as well, as Webster and Plante (1992) suggested. Phonological awareness, as we’ve seen, is important for literacy acquisition. So part of the oral language assessment of a child with or at risk for LLD, particularly a child in the primary grades or one who is reading on a primary-grade level, should include some index of these higher level phonological skills that serve as the foundation for learning to read. There are several ways to approach this assessment. The first is to look at production skills in phonologically demanding contexts. Hodson’s (1986) Multisyllabic Screening Protocol section of the Assessment of Phonological Processes—Revised can be used to measure this aspect of phonological skill. Many standardized tests of phonological awareness also contain subtests that use non-word repetition tasks, since these have been shown to be markers of language impairment (Dollaghan & Campbell, 1998; Graf-Estes et al., 2007), and provide standardized scores. The Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (Wagner, Torgeson, & Rashotte, 2000) and the Children’s Test of Nonword Repetition (Gathercole & Baddeley, 1996) are two examples. Appendix 11-3 presents a list of standardized tests of phonological awareness, indicating which contain non-word repetition subtests. A second way to look at higher level phonological skills in students with LLD is to examine phonological awareness directly. There are a variety of tests of phonological awareness currently on the market. Appendix 11-3 profiles some of these. The pitfall in using these tests is that they can take a good deal of time to deliver a small amount of information (i.e., whether or not the child is at risk for literacy difficulty) that might be inferred as easily from a shorter assessment, information derived from the RTI process, or curriculum-based assessment. A third approach to assessing higher-level phonological impairments was suggested by the work of Catts, Fey, Zhang, and Tomblin (2002); Powell, Stainthorp, Stuart, Garwood, and Quinlan, (2007); and Swank (1994), who advocate assessment of rapid automatized naming (RAN). Bowers and Grieg (2003), Brizzolara et al. (2006), and Wolf et al. (2002) have reviewed evidence showing that RAN, like phonological awareness, is also highly correlated with reading ability. In RAN tasks students are asked to name common objects presented in a series as rapidly as they can. Children also can be asked to produce overlearned series such as days of the week or months of the year. Performance on tasks such as these has been shown to discriminate between good and poor readers. Some standardized tests, such as the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—4 (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003), contain sub-tests that tap this ability. Despite the importance of identifying risk for reading failure, and the known strong associations among non-word repetition, RAN, phonological awareness, and reading, the main goal of this assessment must always be kept in mind. That goal is to identify children in early primary grades who are at risk for reading failure and to provide early, preventive intervention to give them an opportunity to avert this failure. For older students already known to have reading deficits, phonological assessment is less important, and evaluation of other areas of oral language needed to support reading should be our focus. And even for younger children, shorter, informal methods of identifying risk, such as the checklists like the one in Figure 11-2 or suggested by Justice (2006), or simply working with kindergarten and first-grade teachers in monitoring processes like RTI to quickly identify children who are having trouble with standard classroom phonological awareness activities, as Justice and Kaderavek (2004) have suggested, may be just as effective. And when we think about intervening for these problems, Catts (1999a) has reminded us that the aim of these interventions is to teach children to read and spell, not to develop phonological awareness as a “splinter skill.” Once basic phoneme segmentation, sound blending, and letter-sound correspondence have been mastered, we should move on to building other aspects of oral language skill to support reading development, such as vocabulary, fluency, text comprehension, and literate language production, rather than continuing to teach more and more advanced phonological awareness skills. One way is for the clinician to observe in the student’s class and note the kinds of spatial, temporal, logical, and directive vocabulary the teacher uses. These can form the basis for a criterion-referenced vocabulary assessment, in which the student is asked to follow directions containing these words, one target word per direction. For example, suppose the teacher typically tells the students, “Write your name in the upper right-hand corner of the paper, write the date below your name, and number your paper to 20 down the left side.” The clinician might assess the student’s understanding of the vocabulary in these directions by isolating each potential problem word and testing its comprehension in a game-like format, such as the one in Box 11-1. Any words the student has trouble comprehending that are common in the teacher’s instructional language could be targeted as part of the intervention program. Alternatively, the teacher could be made aware of the student’s difficulty, and consultation suggestions could be made to encourage the use of visual cues along with instructions, additional time for the student to process the instruction, and paraphrasing the instruction to give the student an extra chance to understand it. We should remember when working with students with LLD that it is not only the technical, content vocabulary of the texts that might cause these students difficulty. More common spatial terms (above, north); temporal terms (after, following); and connectives (however, consequently) also may cause problems. Nelson (2010) suggests having students read aloud from classroom texts and identifying words they mispronounce as potential sources of vocabulary assessment. Many of the words we’ll want to assess are not easily depicted, though. In such cases, we might ask students to paraphrase a sentence containing the word, or offer several choices and have the student select the best meaning (Nelson, 2010; Ukrainetz, 2007). Alternatively, we could try to get the student to act out or indicate the meaning of the word in some nonverbal way. We might, for example, ask the student to “Show me orbit” with two tennis balls or to “Show me division” with some raisins. For more general assessment, language batteries that include subtests of words that are often difficult for students with LLD can be used. The Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—4 (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003) and the Detroit Tests of Learning Aptitude–Fourth Edition (Hammill, 1998) are two examples. When students score below the normal range on these subtests, an item analysis can be done as an informal assessment of the specific vocabulary items that are hard for the student to understand. For some of the spatial, temporal, and connective words we are concerned about, we can ask the student to act out several versions of the same sentence that differ only by words in the category being tested. Examples of such sentences for informal assessment are given in Box 11-2. Receptive vocabulary is larger than expressive vocabulary in people of all ages. Some students may be able to glean the meaning of an unknown word from its context but would not be able to use the same word appropriately without a more elaborated understanding of it. We talked in Chapter 8 about the complicated relationship between receptive and expressive vocabulary, and the fact that we may want to examine each aspect of word knowledge somewhat independently. In looking at expressive vocabulary skills in the L4L stage, we generally focus two basic components: lexical diversity and word retrieval. The ability to use a flexible, precise vocabulary contributes a great deal to the efficiency of our communication. The Type-Token Ratio (TTR; Templin, 1957) is a measure that has been used traditionally to assess lexical diversity. It involves counting the total number of words (tokens) in a 50-utterance speech sample and dividing this number into the number of different words (types) in the sample. Owen and Leonard (2002) showed that children with SLI did not generally differ from same-age peers on this measure. Watkins, Kelly, Harbers, and Hollis (1995) compared the ability of the TTR as opposed to the Number of Different Words (NDW) and number of total words (NTW) in a speech sample to differentiate children with normal and impaired language development. They found that in speech samples of various sizes, the NDW and NTW measures were more sensitive estimates of children’s lexical diversity than the TTR. Klee (1992), as well as Tilstra & McMaster (2007), reported that both NDW and NTW increased significantly with age and both differentiated children with normal and impaired language. NDW and NTW produced in a conversational speech sample may, then, be the best means we have available to evaluate children’s lexical diversity. These measures can be calculated automatically by computer-assisted speech sample analyses programs such as the Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) (Miller & Chapman, 2006). Leadholm and Miller (1992) presented data on NDW and NTW in the 100-utterance conversational speech samples of typical school-age children in the Madison, Wisconsin, Reference Data Base. These data are summarized in Table 11-1. If NDW and NTW measures are collected from conversational samples of clients’ speech and the values computed fall below the normal ranges given in Table 11-1 (provided clients are from a population similar to that of the Reference Data Base), a deficit in lexical diversity could be diagnosed. Intervention could focus on increasing expressive vocabulary by focusing on words necessary for success in the curriculum. Heilmann, Miller, and Nockerts (2010) also discussed methods of investigating vocabulary diversity in narrative language samples. Table 11-1 Normal range = (±1 standard deviation from group mean). NDW = number of different words; NTW = number of total words. Adapted from Leadholm, B., & Miller, J. (1992). Language sample analysis: The Wisconsin guide. Madison, WI:Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. Another aspect of expressive vocabulary that is important to assess in the L4L stage is word retrieval. As we discussed in Chapter 10, word-finding difficulties are very common in students with LLD. One clue to the presence of a word-retrieval problem would be a much higher score on a receptive vocabulary test, such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—IV (Dunn & Dunn, 2006), than on an expressive vocabulary test, such as the Expressive Vocabulary Test—2 (Williams, 2007). Another would be a teacher report of word-finding problems on one of our referral checklists, like the one in Figure 11-1. We also might hear some word-finding problems in our short conversational interaction, with which we began the assessment session. If we think word retrieval might be a problem, we generally want to establish the fact of the difficulty with a standardized test or a portion of a test that investigates word finding specifically. It is a good idea to document a word-retrieval problem by means of a score on a norm-referenced assessment, rather than making a subjective judgment. Several tests listed in Appendix 11-2, including the Test of Word Finding in Discourse (German, 1991), assess word-retrieval skill. Several others, including the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—4 (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003), the Test of Semantic Skills—Primary (Bowers, LoGiudice, Orman, & Huisingh, 2002), and the Language Processing Test—Revised (Richard & Hanner, 1995), also have subtests that assess word finding, on which item analyses can be done for criterion-referenced assessment. If a word-finding deficit is identified, we want to try to teach some word-finding strategies as part of our intervention program. Chapter 12 will present suggestions for such strategies. Brackenbury and Pye (2005) discuss the importance of looking beyond vocabulary when assessing semantic skills. Several other aspects of semantic development that can be considered for assessment are discussed below. The ability to acquire new words quickly, with limited meanings, from very abbreviated exposure, is one of the ways in which children’s vocabularies are able to grow so rapidly. Often called quick incidental learning (QUIL), or fast-mapping, this capacity has been shown to be less well developed in children with language disorders (Dollaghan, 1987; Eyer et al., 2002). Many studies of QUIL use nonsense words to determine a child’s ability to learn a new word from naturalistic interactions, and this ability is often considered a good way to assess a child’s intrinsic language skill, especially in children who are not native speakers of English or who may have impoverished language experience (Branckenbury & Pye, 2005). One way to assess QUIL clinically is to use the Diagnostic Evaluation of Language Variation (DELV; Seymour, Roeper, & de Villiers, 2005), which contains a QUIL subtest. Suppose we do our complex sentence analysis of a speech sample (which we’ll discuss in the next section) and find very little use of any syntactically complex forms. We can then look at the sample for evidence of presyntactic expression of semantic relations between propositions. In normal development, children first express these relations by merely juxtaposing two clauses (“Mommy here, Daddy gone”). Later they conjoin with nonspecific conjunctions, primarily and. Students with LLD may show this kind of immature attempt at relating ideas. The kinds of relations we would expect to see emerging (Lahey, 1988) include the following: 1. Temporal (“Eat dinner and go to sleep.”) 2. Causal (“Go to store and buy shoes.”) 3. Conditional (“Eat dinner, go outside.”) 4. Epistemic (“I think draw pink.”) 5. Notice-perception (“Show me how do a somersault.”) 6. Specification (“I have a dog and it’s brown.”) 7. Adversative (“The girls sit here and the boys sit there.”) We’ve talked before about the need to assess syntax and morphology in the receptive and expressive modalities, and why it’s important: the fact that children frequently produce sentence forms even when they fail to perform correctly on comprehension tests of these same forms in settings where nonlinguistic cues have been removed (Chapman, 1978; Miller & Paul, 1995). And there’s an additional reason: as Scott (2009) shows, children with LLD are often delayed in understanding the kinds of complex sentences found in school reading materials. Identifying and remediating these delays are an excellent way for SLPs to support literacy development in students with LLD. When we help children learn to understand these sentences in oral form, this understanding will support their reading comprehension. So assessing and treating receptive syntactic difficulties in oral formats is an excellent way for the SLP to make a contribution to children’s developing literacy. We’ve also talked about the importance of assessing comprehension strategies. Paul (2000b) discussed the fact that children with LLD are likely to persist much longer than normally speaking peers in using several types of these strategies, particularly when confronted with complex sentences. Some of the difficulties that students with LLD have in understanding complex language can be traced to this protracted reliance on information other than that contained in the syntax of the sentence. Students at this stage may need to be taught how to get beyond their dependence on these processing shortcuts and to extract the appropriate information from syntactic forms. Sentences particularly vulnerable to this type of misinterpretation by students with LLD include passives (“A student is seen by a teacher” misinterpreted as “student sees teacher”); sentences with relative clauses embedded in the center between the subject noun phrase and the main verb (“The boy who hit the girl ran away” misinterpreted as “girl ran away”); and sentences that certain adverbial conjunctions (“Before you eat your dessert, turn off the TV” misinterpreted as “eat dessert then turn off TV”). The general strategy for assessing syntactic and morphological comprehension we discussed in Chapter 8 will differ somewhat for children in the L4L period, because standardized tests may not identify all the comprehension deficits that can give students problems in the classroom. So we’ll give you a version of the general strategy for assessing grammatical comprehension that can be used in the L4L stage: 1. Use a standardized test of receptive syntax and morphology to determine deficits in this area. If the student performs below the normal range, use criterion-referenced decontextualized procedures, such as judgment tasks, to probe forms that appear to be causing trouble on the standardized measure. Look for use of comprehension strategies in responses to these tasks. If the student scores within the normal range but teacher referral indicates problems in classroom comprehension, observe teacher language in the classroom and textbook language (as outlined in the vocabulary section earlier in the chapter). Identify syntactic structures that may be causing difficulty. Some likely candidates include complex sentences with adverbial conjunctions (because, so, after, although, unless, etc.); sentences with relative clauses; passive sentences; and other sentences with unusual word order, such as pseudoclefts (“The one who lost the wallet was Maria”) (Eisenberg, 2007; Wallach & Miller, 1988). Probe comprehension of these structures with criterion-referenced, decontextualized procedures, such as judgment tasks (see Miller & Paul, 1995, for suggestions). Again, look for operation of strategies. 2. If the client performs poorly on the decontextualized criterion-referenced assessments, test the same forms in a contextualized format, providing familiar scripts and nonlinguistic contexts; facial, gestural, and intonational cues; language closely tied to objects in the immediate environment; and expected instructions. 3. If the child does better in this contextualized format, uses typical strategies, or both, then compare performance on comprehension to production. Target forms and structures the child comprehends well but does not produce as initial targets for a production approach. Target structures the child does not comprehend well for focused stimulation or verbal script approaches to work on comprehension and production in tandem. 4. If the child does not do better in the contextualized format and does not use strategies, provide structured input with complexity controlled, using more hybrid and clinician-directed activities for both comprehension and production. In Chapter 2, we talked about several basic means for evaluating comprehension in decontextualized settings. These included picture pointing, behavioral compliance, object manipulation, and judgment. We’ve talked already in Chapter 8 about ways of using some of these methods. These methods will continue to be appropriate for use with students with LLD. In the L4L period, we can add judgment tasks to our repertoire, since school-age children are developmentally ready to make judgments of grammaticality. Judgment tasks are very convenient for assessment, because they don’t require picturing or acting out linguistic stimuli. We can simply present a set of sentences and ask the client to judge whether they are in some sense “OK.” We can use judgment tasks in a variety of ways to assess several areas of language competence. For the moment, though, let’s look at two ways that are well-suited to assessing syntactic comprehension: judgment of semantic acceptability and judgment of appropriate interpretation. This method involves presenting a series of sentences and having the student tell whether each is “OK” or “silly.” Alternatively, we can tell the student that we have two people, one who always says normal things and the other who always says ridiculous things. The “OK” picture can be of an ordinary-looking chap, such as the one in Figure 11-4. The “silly” picture can be a clownlike, silly person, as in Figure 11-5. We can display the pictures and give examples of OK and silly things each might say. We can then ask the student to point to the picture of the character who would say each sentence. We would then read the student a list of sentences that require him or her to understand a sentence type in order to decide whether a sentence is OK or silly. Passive sentences, for example, like those listed in Box 11-3, can be probed this way. A second way to use judgment tasks to assess comprehension in the L4L stage is to offer students two interpretations of a sentence and ask them to decide which is correct; alternatively we can offer one interpretation and ask students to judge whether it is correct. If we are assessing understanding of sentences with adverbial clauses, for example, we can say, “The boy brushed his teeth after he ate his sandwich.” We can then mime the two actions in correct order (eat sandwich, brush teeth) and ask, “Did I do it right?” We can then present other similar sentences and offer both correct and incorrect interpretations for the student to judge. Table 11-2 presents an example of this type of assessment for center-embedded relative clause sentences. Table 11-2 If students respond incorrectly to these decontextualized comprehension activities, we can look for the use of strategies in their responses. The two types most likely to be used in the L4L period are probable-event or probable-order-of-event strategies and word-order or order-of-mention strategies. Evans and MacWhinney (1999) found evidence for the use of both these strategies in school-aged children with language impairments. Probable-event and probable-order-of-event strategies involve interpreting sentences to mean what we usually expect to happen. This strategy is similar to that used by preschoolers to interpret passive sentences. Preschoolers may correctly interpret “The dog was fed by the boy,” for example. They can do this not because they understand passive sentences, but because they rely more on their knowledge of how things usually happen (boys usually feed dogs, rather than vice versa) than on syntactic form. Some students with LLD may continue to use this strategy, even though normally developing children move beyond it by 4 or 5 years of age. Students with LLD also may misunderstand a sentence such as, “Before you wash your hair, dry your face” for the same reason. Ordinarily we would wash our hair before drying our face, but this sentence tells the listener to do something out of the ordinary. The student with LLD may mistakenly depend more on knowledge of the order in which things usually happen than on linguistic form. If a student seems to be having trouble with sentences with adverbial clauses, we can assess use of this strategy by giving several sentences that contain unusual orders of events and have the student act them out. For passives, we can use the assessment in Box 11-3 and note whether the student does more poorly on the improbable-event sentences than the probable-event ones. If so, the probable-event strategy can be seen to operate. The second kind of strategy we are likely to find in children with LLD is the word-order or order-of-mention strategy. Evans and MacWhinney (1999) and Paul (1990) reported that children with expressive language disorders are especially likely to use this strategy. Normally speaking children move beyond it by about age 7, but students with LLD may still use it into adolescence. We can see this strategy operating in assessments such as those in Table 11-2 and Box 11-3. Students with LLD may consistently misinterpret these sentences. For passives, they may interpret the first noun as the agent of the action, rather than the object, as the passive sentence form requires. “A hot dog is cooked by a girl,” for example, will be understood as “hot dog cooks girl.” For center-embedded relatives, the last noun-verb-noun sequence may be interpreted as the agent-action-object message of the sentence. So, for instance, “The cow that bit the goat was called Sadie” will be interpreted as “the goat was called Sadie.” We’ll talk about some techniques for providing intervention for these difficulties in the next chapter.

Assessing students’ language for learning

Child and family in the assessment process

Identifying students for communication assessment

Screening

RTI, referral, and case finding

Monitoring progress in RTI

Evaluation for special educational needs

Using standardized tests in the L4L stage

Criterion-referenced assessment and behavioral observation in the L4L stage

Phonology

Semantics

Receptive vocabulary

Instructional vocabulary

Textbook vocabulary

Expressive vocabulary

Lexical diversity

NDW

NTW

Age

1 SD–

1 SD+

1 SD–

1 SD+

5-year-olds

156

206

439

602

7-year-olds

173

212

457

622

9-year-olds

183

235

496

687

11-year-olds

191

267

518

868

Word retrieval

Other semantic skills

Quick incidental learning (fast mapping)

Semantic relations between clauses

Syntax and morphology

A strategy for assessing receptive syntax and morphology

Criterion-referenced methods for assessing receptive syntax and morphology

Decontextualized methods

Judgment of semantic acceptability

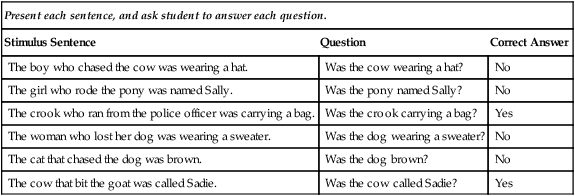

Judgment of appropriate interpretation

Present each sentence, and ask student to answer each question.

Stimulus Sentence

Question

Correct Answer

The boy who chased the cow was wearing a hat.

Was the cow wearing a hat?

No

The girl who rode the pony was named Sally.

Was the pony named Sally?

No

The crook who ran from the police officer was carrying a bag.

Was the crook carrying a bag?

Yes

The woman who lost her dog was wearing a sweater.

Was the dog wearing a sweater?

No

The cat that chased the dog was brown.

Was the dog brown?

No

The cow that bit the goat was called Sadie.

Was the cow called Sadie?

Yes

Assessing use of comprehension strategies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Assessing students’ language for learning

Maria had been doing well in second grade until her bike accident. While riding without a helmet one day, she was struck by a car. She spent 3 days in a coma, and when she first emerged from it, she didn’t speak at all. After several weeks in the hospital, where she received physical, occupational, and speech therapy, she was able to go home. She spent several months out of school, receiving home tutoring and more therapy. She returned to school the next year, by which time she had recovered her speech but still had some problems with her gait and fine motor skills. She continued to see the occupational and physical therapists but was thought to be doing all right with her language. She seemed quiet and never caused any trouble. On the playground, she kept to herself and didn’t get involved in what the other children were doing. She was meek and somewhat shy, but always eager to please the teacher. She seemed to have regressed somewhat in her reading, which was above grade level before the accident, but she managed to follow the simple, repetitive material used in the reading program in her second-grade class, which she was repeating because she’d missed so much time the previous year. When she spoke, her sentences were short, but that seemed to be more because of her shyness than anything else. When she got to third grade, though, she suddenly ran into trouble. She couldn’t follow directions. She couldn’t seem to answer the questions the teacher posed for class discussion. She was unable to read the books used for social studies and science. She began to withdraw, sometimes going for days without saying a word. She complained of stomach aches and often asked to spend time in the nurse’s office. The nurse called her family to discuss the problem. They said that Maria had started saying she was “dumb” and didn’t want to go to school because she was too “stupid.” They reported being very upset to find her crying in bed on school nights. The school nurse suggested to Maria’s teacher that Maria be referred for an evaluation of special educational needs.

Maria had been doing well in second grade until her bike accident. While riding without a helmet one day, she was struck by a car. She spent 3 days in a coma, and when she first emerged from it, she didn’t speak at all. After several weeks in the hospital, where she received physical, occupational, and speech therapy, she was able to go home. She spent several months out of school, receiving home tutoring and more therapy. She returned to school the next year, by which time she had recovered her speech but still had some problems with her gait and fine motor skills. She continued to see the occupational and physical therapists but was thought to be doing all right with her language. She seemed quiet and never caused any trouble. On the playground, she kept to herself and didn’t get involved in what the other children were doing. She was meek and somewhat shy, but always eager to please the teacher. She seemed to have regressed somewhat in her reading, which was above grade level before the accident, but she managed to follow the simple, repetitive material used in the reading program in her second-grade class, which she was repeating because she’d missed so much time the previous year. When she spoke, her sentences were short, but that seemed to be more because of her shyness than anything else. When she got to third grade, though, she suddenly ran into trouble. She couldn’t follow directions. She couldn’t seem to answer the questions the teacher posed for class discussion. She was unable to read the books used for social studies and science. She began to withdraw, sometimes going for days without saying a word. She complained of stomach aches and often asked to spend time in the nurse’s office. The nurse called her family to discuss the problem. They said that Maria had started saying she was “dumb” and didn’t want to go to school because she was too “stupid.” They reported being very upset to find her crying in bed on school nights. The school nurse suggested to Maria’s teacher that Maria be referred for an evaluation of special educational needs.