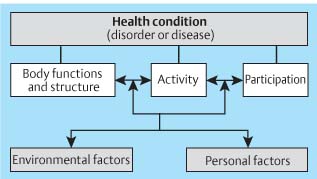

3 Assessment 3.1 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health In different phases and stages of a patient’s rehabilitation, healthcare professionals may take on different roles according to the patient’s needs at that moment: fellow human being, supervisor, guide, informant, professional, helper, or carer. These roles depend on where the patient is in his rehabilitation process and his current needs. Healthcare professionals diagnose, treat and inform, adapt, plan, and structure the rehabilitation together with the patient, taking into perspective the patient’s potential and limitations as a person, as a whole. Multidisciplinary teamwork brings together each profession’s general and specific competencies and role, and the patient has his own competencies. Together, these give insight into the challenges in the rehabilitation process of the individual patient. Possibly, the healthcare professionals’ most important task is to find possibilities and potential—the positive building blocks within the patient and in his network of carers—that may enhance his progress. The patient’s needs are central to the choice of interventions. This chapter discusses • The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) • Physiotherapy assessment • Outcome measures The ICF is a tool used to classify different aspects and factors which influence a person’s life and describe how people live with their health condition. ICF is a classification of health and health-related domains that describe body functions and structures, activities, and participation. The domains are classified from the body, the individual, and societal perspectives. As an individual’s functioning and disability occurs in a particular context, the ICF also includes a list of environmental factors. The ICF is useful to understand and measure health outcomes. Itcan be used in clinical settings, health services, or surveys at the individual or population level. Thus it complements the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition (ICD-10) and looks beyond mortality and disease. By using the ICF, there is also the hope that healthcare professionals will communicate in the same language. The last version of the ICF was published in 2001, and it moved away from being a “consequences of disease” classification (1980 version) to become a “components of health” classification (WHO 2001, Introduction p. 4). The ICF is divided into different sections for body functions, body structures, activities and participation, and environmental factors (ICF 2006, online version) (Table 3.1). • Body function is a classification of the physiologic and psychologic systems of the body • Body structure classifies anatomic parts of the body: organs, extremities, and their components • Impairments are problems of body functions and structures • Activities and participation covers all activities performed by individuals • Limitations are problems the individual may experience in the performance of activities • Participation classifies the involvement in life situations by the individual in relation to health, body functions and structures, activities, and relations • Restrictions are problems that an individual may encounter in the way or level of participation in life situations • Environmental factors make up the physical, social, and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their life As well as these sections, the ICF involves another area that is not classified: • Personal factors are the particular background of an individual’s life and living, and comprises features of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health states, which may be age, sex, experiences, personal beliefs, religion, lifestyle, etc. The interaction between these factors is illustrated in Figure 3.1 (from ICIDH-2 1999). The interaction among these factors is dynamic: interventions at one level have the potential to modify other related elements. ICF may be used to ensure that all aspects of a person’s situation have been evaluated as a basis for his rehabilitation process. Fig. 3.1 The interrelationship between the different factors of the ICF (adapted from: ICF, WHO 2006).

3.1 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

Body functions 1. Mental functions 2. Sensory functions and pain 3. Voice and speech functions 4. Functions of the cardiovascular, hematologic, immunologic, and respiratory systems 5. Functions of the digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems 6. Genitourinary and reproductive functions 7. Neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related function 8. Functions of the skin and related structures |

Body structures 1. Structures of the nervous system 2. The eye, ear, and related structures 3. Structures involved in voice and speech 4. Structures of the cardiovascular, immunologic, and respiratory systems 5. Structures related to the digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems 6. Structures related to the genitourinary and reproductive systems 7. Structures related to movement 8. Skin and related structures |

Activities and participation 1. Learning and applying knowledge 2. General tasks and demands 3. Communication 4. Mobility 5. Self-care 6. Domestic life 7. Interpersonal interactions and relationships 8. Major life areas 9. Community, social, and civic life |

Environmental factors 1. Products and technology 2. Natural environment and man-made changes to environment 3. Support and relationships 4. Attitudes 5. Services, systems, and policies |

3.2 Physiotherapy Assessment

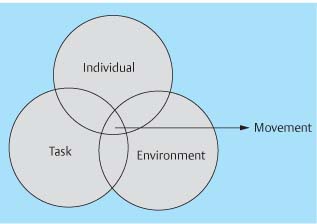

All aspects of motor, sensory, cognitive, and perceptual functions are important for action as illustrated by a model first presented by Shumway-Cook and Woollacott (2001) (Fig. 3.2). The physiotherapist has a specific and important role in the regaining, learning, and maintenance of physical function.

The aim of assessment is to understand the patient’s situation. The therapist has to come to know who he is, how he lives, his networks and family relations, work situation, and his resources, and at the same time analyze his movement function. Assessment is therefore both resource and problem orientated. The aim of physiotherapy is the improvement of physical function to the patient’s full potential to enable him to participate as actively as possible in his life again. The assessment should indicate what functions have been spared in relation to the regaining and learning of activities, postural control and movement, which functions have been damaged or are dysfunctional, and the consequences for the patient. Assessment leads to information which allows the therapist to formulate hypotheses as to cause and effect of the patient’s problems, and evaluating which systems within the central nervous system (CNS) seem to be functional or dysfunctional and then using this as a foundation for treatment interventions. Knowledge of components of movement which are important for balance and extremity function is a basis for both assessment and treatment. The goal of assessment and treatment is to define the patient’s potential and how he can reach optimal function within the limits of available resources.

Evaluating the patient’s potential is an important goal of assessment

Neuropsychologic dysfunction and sensory loss have in many cases been used to decide on the patient’s rehabilitation potential in the acute phase after a stroke. These early symptoms are not a sign of the patient’s real prognosis: perception and cognitive dysfunctions in most cases do improve, as the patient is more oriented to his environment. Thus focus on sensory, perceptual, and cognitive problems alone may lead to a more negative view of the patient’s potential. Things take time; the patient must be allowed time for reflection before reaching conclusions about the prognosis and thereby the level of rehabilitation effort the patient needs/is offered. The role of the physiotherapist is to assess what activities the patient is able to do, how he solves his movement tasks and reaches his goals, and why he moves as he does. This assessment forms the basis for physiotherapy interventions.

Occupational therapist Christine Nilson said the following about Berta Bobath in 1991: “She encouraged my creativity and taught me to see each patient as an individual. She offered problem-solving skills that led so logically to treatment intervention” (Schleichkorn 1992, p. 98). Observational analysis of movement during activity is the most important tool of the assessment, and leads on to appropriate handling of the patient followed by clinical reasoning and treatment interventions.

Fig. 3.2 Illustration of how movement is influenced by factors within the individual himself, his environment, and the goal of his actions.

Handling is both an assessment tool and an intervention, and leads to a response from the patient. During handling the aim is to influence the patient’s ability to move and his response to being moved. His response is important to determine the level of his response and his ability to learn, and evaluation of the response is therefore important for the assessment. In this way, assessment and treatment are interlinked processes and cannot be separated. During assessment, the therapist collects information and starts a process of clinical reasoning to form hypotheses about why the patient moves as he does—hypotheses about the patient’s main problem regarding activity and function. Treatment interventions are started, the results continuously evaluated, and hypotheses are discarded if treatment does not improve the patient’s motor control, and new hypotheses are formulated as the treatment progresses. In general, the assessment follows the following process:

• History

• Functional activity

• Body functions and structures

• Clinical reasoning

• Outcome measures

• Evaluation and documentation

History

This part of the assessment aims at getting to know the patient and view him as a whole in the knowledge that rehabilitation is a process that often takes many years. The patient is assessed in relation to the ICF dimensions—participation, activity, and body functions and structures—both as he previously functioned and how he presently functions. The therapist has in mind the patient’s likely potential, resources, and possible problem areas. It is of essential importance to form a relationship founded on respect and trust, and gain information on social aspects, his roles, medical history, present situation, needs, and wishes. In a team setting, the different members of the team can decide whether they wish to interview the patient and his carer together or separately. Preferably, they should decide on dividing the interview in a way that the patient does not have to tell the same story again and again to the whole team.

Social Aspects

• Marital status, family, and close social network

• Social roles, his needs and wishes

• Housing

• Hobbies and leisure activities

• Work situation

– Profession, type of position/work, tasks

– Unemployed or pensioner? Reasons

Medical History

• Previous level of function

– Physically: vision, hearing, problem areas, use of aids or assistive devises (walking aids, wheelchair, orthopedic shoes, orthotics, and similar), level of activity

– Mental function

– Other diseases

– Medication

• Previous treatments

– Physiotherapy. For what reason? Effect of treatment?

– Other

• Previous contact with the health service

• Present illness or disorder

• Results from medical examinations and tests, e. g., computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), X-rays, neurophysiologic tests

• Any contraindications or any aspects of treatment that may need special attention

• Factors that may exacerbate or improve the patient’s motor control and why—as the patient sees it. The patient is often able to verbalize or express his experience of how different things may influence each other, i. e., stress and tone

• The patient’s perception of his own situation: frustrations, hopes, needs, goals

If the patient is unable to communicate, this information needs to be collected from his carers, who are often able to give good information and insight.

A person who suffers from acute illness or trauma undergoes catastrophic changes in his life, which may last for a short or long time or may even be permanent. The therapist needs to find out where he is in his own rehabilitation process: Is he in shock or have he and his carers started a process of reorientation. Time and information is of the essence and may be the most important intervention besides specific treatment and empathy. It does take time to realize and understand what has happened, and it is not possible to get an overview of the extent or consequences of the lesion for the patient at once.

Functional Activity

This part of the assessment builds on interview, observational analysis, and handling together. The aim is to clarify what the patient is able to do, his degree of independence, and his ability to cooperate and interact.

During the interview the patient is asked what activities of daily living (ADLs), personal hygiene, instrumental ADLs (IADL, e. g., going to the shops), and leisure activities he is able to do which are relevant to the situation now. His ability for activities informs the therapist of:

• General condition and general level and ability of movement

• Communication function

• Functional activity:

– Quantity: What the patient is able to do

– Quality: How the patient moves

– Clinical reasoning process: Why does he move in this way

• Use of aids

If the patient is in an acute phase after a CNS lesion, both his level of activity and his movement control will alter quickly due to spontaneous recovery and increased learning potential. The therapist needs to evaluate the patient’s condition and abilities continuously to adapt and change her interventions appropriately to enhance the patient’s recovery.

General Condition

Observation of the patient’s general condition provides the initial impression of the patient’s status and how he feels:

• General condition and respiration

• Stamina

• Comfort and feeling of security

• Effort

• Ability to relax

• General autonomic function (see p. 156)

Communication

During the interview and observation of the patient’s general condition the therapist forms an impression of the patient’s verbal and symbolic understanding. Does he understand words? Does he understand nonverbal instructions given through the use of gestures?

Functional Activity: What? How? Why?

Berta Bobath said, “See what you see, and not what you think you see” (cited in Schleichkorn 1992, p.48). Observation of the patient’s activity starts when the therapist sees the patient for the first time, and before any form of intervention, such as transferring to a plinth, and before he is asked to change his clothing if appropriate. The patients’ movement repertoire is analyzed through functional activity (Table 3.2). If he has the ability to stand or walk, transfer, and dress and undress in sitting and standing, these functions are analyzed first, as appropriate. The patient is met at the level he functions; if he is unable to do any of the above-mentioned activities, his ability to accept the base of support, to maintain a position and move within it, his ability to be placed are assessed. A general observation informs the therapist of:

• Feeling of security

• Effort

• Time, efficiency, appropriateness

• Posture

• Balance (postural control, righting, and protection)

• Patterns of movement, sequence of activation and alignment

• Selective function of the extremities. Ability to vary and change

• Tone

• Compensatory strategies

• Associated reactions

• Sensation

• Perception: attention to and experience of one’s own body in relation to the environment

• Cognition: attentiveness, understanding, focus, problem-solving abilities, memory, concentration, and insight

• What functional activities is the patient able to perform? Is he sitting passively in a chair or lying in a bed without the ability to move? How does he respond when facilitated or helped? Can he transfer, stand, or walk and how safe is he in those situations?

The analysis is both resource and problem oriented. It is supposed to give answers to what the patient can realistically perform independently, when he needs support, and how he solves his tasks through movement. It is important to discuss with the multidisciplinary team and the patient’s carers to form as full a picture as possible, as well as observing the patient when he is not aware of being observed.

• Interaction with the environment | The patient’s ability to interact with the environment: – The patient moves in relation to the environment. – The environment, people, and objects move in relation to the patient, gives information on the patient’s perceptual and dual task capacity and how automatic his balance is. |

• Transfers | For example in a wheelchair or walking depending on his functional level, weight transference in different postural sets of sitting and standing, in the transfers standing-sitting/chair-bed or other chair/in and out of bed, i. e., his ability to control and vary movement. The key words are postural stability and orientation, eccentric and concentric control. What is he able to do by himself, what does he need help for, and why? The transfers from sitting to supine and vice versa are possibly the most complex and demanding tasks a person performs in his daily life. This transfer requires that we are able to eccentrically grade the movement from sitting to supine through a continuous changing relationship with the base of support, rotational components to align the body to the new base, eccentric work combined with aspects of specific concentric activity to lower the body down. Sitting up from supine requires a selective, graded, varied recruitment of motor activity through rotation to align the body in sitting on the edge of the bed. Both these transfers need the combination of flexion, extension, and rotational components, and a controlled recruitment of motor units for selective eccentric/concentric activation based on postural control from one position to another. The relationships with gravity and the base of support are very different in the postural sets of sitting and supine, and therefore require different muscle activation to achieve and maintain. There is a conflict between the complexity of this task and the expectation from health personnel that the patient should be able to achieve this function as soon as possible for the sake of independence. For most patients, the transfer from sitting to standing, standing and walking is easier than getting in and out of bed. |

• Dressing and undressing | Dressing and undressing require both postural control and righting to enable the patient to weight transfer in sitting or standing and free their arms for function (see Chapter 2, Figs. 2.40–2.43 and 2.54–2.60). For most patients dressing and undressing will also require learning, as many must find new strategies or even wear different clothes to master this task. |

• Personal hygiene | Is the patient able to manage visits to the bathroom by himself? Is he continent, does he participate in washing himself in the morning? Is he used to taking a shower or bath, and can he manage this? Is he able to get out of bed, to sit, or stand for any of these functions? If not, what help does he need? Why? |

• Eating/drinking | Does the patient eat or drink by himself? Does he spill food/drink, why? Sensation in his face may be poor, his motor control around his mouth may be decreased, or there may be perceptual/cognitive dysfunctions. If the patient coughs when he drinks or eats, he may have dysphagia. This is often a problem that is overlooked if the problems are small, but may cause complications for nutrition or for the patient’s lung function and be an important social factor. |

• Perception and cognition (see also Body Function and Structures) | How does the patient interact with his own body and with the environment? Is he able to avoid obstacles; is he attentive to people, furniture, objects? Is he able to vary his movement repertoire in relation to the room and what is in it? If in a wheelchair, how does he relate to it? Can he maneuver it himself, how? How does he problem solve footplates, brakes, and table. If he is able to dress and undress or participate in this activity, is he able to cross his body to undress sleeves, does he find his arms and legs? How does he solve the task? Is he focused, attentive—to what degree? Does he finish what he has started? If the patient has suffered a stroke, how does he take care of his affected arm during these tasks? If the patient has problems understanding or responding, either to verbal information or problem solving a “new” situation, he may have cognitive deficits. The therapist needs to find out if he has organic deficits (vision or hearing) or cognitive problems. His ability to problem solve may be assessed in all practical situations: use of wheelchair or walking aids, during transfers or any other relevant activity. If the patient seems to have perceptual or cognitive deficits, a multidisciplinary assessment is of special importance. Nurses, assistants, carers may inform the team about how the patient problem solves and masters different situations through the day, and about his concentration, attention, moods, insight, self interest and interest in his environment. Neuropsychologists and occupational therapists may assess the patient more specifically, and give advice on how the patient should be helped in daily activities to enhance his perception and cognition. The patient’s perceptual and cognitive function should be assessed and reevaluated over time for appropriate treatment and to evaluate the consequences for the patient’s function and life. |

Use of Aids

Does the patient need aids: a wheelchair, walking aids, other technical or orthopedic aids? Why?

Information from other health professionals working with the patient gives a more complete picture of the patient’s strengths and weaknesses.

Body Functions and Structures

This part of the assessment involves observation, handling, and analysis. Important factors are:

• Quality of movement, movement patterns, stability, and mobility

• Sensation, perception, and learned nonuse

• Pain

• Autonomic function

Observation

This informs on overall functions, both visible and invisible aspects; spatial relationships, perception of one’s own body and its relationship with the environment, other perceptual and problem-solving abilities, concentration, attention, motivation, mood, and orientation as well as sensation and movement ability. Therapists tend to assess the patient in different positions, and because we move between different postures and positions normally, the patient is assessed in relation to dynamic activity. Assessment in supine may give additional information about tone, alignment, and range of movement, if appropriate. If the patient experiences increased problems with hypertonia during the night or in the morning before or as he is getting out of bed, his sleeping patterns and positions need to be assessed specifically.

Handling

During handling the therapist assesses how movement is performed—initiation, recruitment, sequence, alignment—and gains information about muscle activity, stability, and movement within and between key areas. The therapists then forms hypotheses about which key areas seem to be most affected or fixed. Through an invitation to move through handling and facilitation, quality of movement and muscle activity as well as range of movement is assessed further. Assessment is not passive; it is the patient’s ability to recruit activity and move which is important. Through correction of components that seem deviant or malaligned, the therapist again invites the patient to move through handling. Has anything changed, positively or negatively? In this way, the therapist gets an impression of tone distribution, stability, postural control and balance, tempo and selectivity, and the ability to vary and adapt.

Analysis

Movement is analyzed through muscle activity, interplay, alignment, patterns of movement, which may have consequences for the patient’s ability to regain and learn movement. Observation and handling is not performed satisfactorily without the patient being adequately undressed, preferably wearing short trousers (with a bra or sun-top for women). If the patient is unwilling to undress to this level, even if other people are not around and after being given information on the importance of being undressed to allow the therapist to analyze his movement properly, his wishes must be respected.

Assessment of body functions and structures require the therapist to have a good knowledge of normal movement and to be competent to analyze interplay of movement specifically. This part of the assessment is qualitative and resource and problem-oriented. The therapist needs to gain insight into how the patient moves, what he is able to perform, and how movement is being performed. This requires an analysis of body functions and structures in the activity dimension (ICF). Handling allows the formation of hypotheses of which neuromuscular interplay brings the patient to where he is. The musculature changes alignment and moves joints under the influence of gravity. Component analysis is the analysis of neuromuscular activity.

Knowledge of normal movement and prerequisites for balance and movement in normal situations allows the analysis of deviations from normal movement. The patient’s way of moving is analyzed in relation to hypotheses of how he moved before the CNS lesion.

Quality of Movement

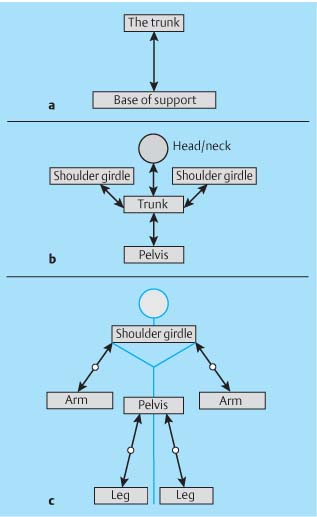

The therapist needs to have a picture in mind of how the patient might have previously moved, and view the deviations in this light. It is complicated to analyze simultaneously both how the patient is moving and the underlying neuromuscular connections and the consequences this may have for the patient’s function. It may be easier to divide this part into phases: What neuromuscular activity does the patient recruit to maintain a posture or to move (Fig. 3.3)?

The following qualities are evaluated in relevant postural sets and activities:

• Midline orientation: Does the patient move in all planes and seem to have a perceptual relationship to his own body and the environment?

• Ability to move to and from the physical base of support is evaluated through observation and handling. Is the patient able to adapt his tone and neuromuscular activity to be where he is, to maintain the postural set, and move through weight transference and righting to another postural set? For example, if the patient is sitting, the therapist may place her hands over his greater trochanters, sense the hips, the position of the pelvis, his ischial tuberosities, and the muscle activity in the area. The patient is facilitated to move in different directions and the therapist observes senses and analyzes the adaptive movements of the related key areas during weight transference in different directions. The therapist observes and handles the feet and the hands to assess their adaptive abilities: to weight transfer on to the feet or the shaping of the hand to different objects; reach, grasp, and let go.

• Interplay and interrelationship between different key areas: The key areas are assessed both individually and to see how they adapt to each other through movement. Neuromuscular activity is analyzed in the specific postural sets the patient adopts and moves within, i. e., the patient’s relationship to gravity and the base of support.

– The interplay between the trunk, head and neck, the pelvic girdle, and the shoulder girdles gives information on the patient’s postural control, especially core stability and his righting ability.

– Is the patient able to maintain postural stability as he moves his extremities (or they are moved for him), or is the patient displaced or dependent on fixation through the arms/legs to maintain balance?

– The interplay between the hands/feet and the proximal key areas informs of postural control, selectivity, patterns of movement, and the ability to vary in relation to the goal (task).

– Is the patient able to support himself using arms and legs and move his trunk in relation to his extremities?

• Patterns of movement, sequence of activation, and biomechanical factors: Joint position and range, rotatory components, alignment inform of which neuromuscular activity the patient has used to get where he is and is currently using. Does the patient recruit anticipatory postural activity to maintain stability for movement? Does this background activity vary with different tasks? Is selectivity present in all parts or are some movement components missing or inadequate?

• Selective control of movement: The individual movement and neuromuscular activity within the key areas. Is there freedom of movement and activity in all planes? Selectivity is controlled activity of one body part based on stability in another. Does the trunk rotate too early or too little during arm movement; is the head free to scan the environment? Is the scapulae free and stable or does it glide too early when the other shoulder girdle is moved during tasks?

• Muscle quality: flexibility, length, and elasticity. Does the musculature exhibit qualities needed for interplay of eccentric and concentric activity? Is compartmentalization maintained (see Chapter 1.1 Systems Control, The Neuromuscular System).

Fig. 3.3a–c

a Observation and analysis of the patient’s line of gravity in relation to the base of support. Where does it fall, and which neuromuscular activity must the patient recruit to be where he is and to move from there? The trunk, head, and neck are central to balance and require coordinated movement in three planes. Analysis of this relationship gives information on:

– Holistic function and balance

– Midline: symmetry/asymmetry

– Weight distribution: active/passive (weight)

b Analysis of the connection and interplay between the central and proximal key areas

– Interplay

– Selectivity

– Variation and change

– Mutual influence

c Analysis of patterns of movement within the extremities and the distal–proximal relationships

– Adaptation to the environment

– Patterns

– Selectivity

– Mutual influence

– Normal, adaptable tone that varies in relation to different postural sets and activity

– Hypotonia: tone that is less than that which would seem appropriate or expected for the activity. Is there an increased sense of weight (limpness or flaccidity, inactivity, weakness) during movement or when moving and handling the patient?

– Hypertonia: more tone than would seem appropriate or expected for the activity. Is there resistance or increased assistance to movement in one direction? Where? Which qualities does this express?

– The presence of associated reactions: when are they expressed? In which situations (see Chapter 1.3, p. 61)? Is it possible to facilitate the patient’s postural control and movement so that the associated reactions are diminished?

– Spasticity (see Chapter 1.3, p. 59) or secondary problems of soft tissue changes?

• Compensatory strategies. Which strategies does the patient employ to solve motor tasks? Appropriate or inappropriate? Is it possible to facilitate the patient to make such strategies to a certain degree superfluous?

• Does the patient respond to facilitation? Is it possible to facilitate the patient to take over and make the movements his own (placing)? If not, why not? Is there resistance to movement, where? Is there islittle or no muscular activation, is the stimulation strong enough? What are the consequences? If the patient does respond, where is the initiation, how is the pattern?

The patient’s response to being handled gives important information about how the patient may be facilitated, if he tolerates the closeness of the therapist and if he interprets the information and demands that she transmits through handling. This requires that the therapist is precise in her handling and facilitation.

Sensation, Perception, and Learned Nonuse

Observational analysis gives the therapist an impression of whether information in integrated in the patient’s CNS or not, and if this information is being used in relation to the patient’s ability to move. Sensory testing may be performed to assess the patient’s conscious awareness of sensory impulses, which is important especially for stereognosis and dexterity of the hand (see Chapter 1.1 Systems Control, Stereognostic Sense). Testing shows how sensory information is transmitted and processed within the CNS. Poor sensation may be due to lesions of the ascending systems directly or due to sensory perception, i. e., association areas. If sensory perception is affected, the CNS does not interpret the information that it receives, which is a problem with sensory integration and not reception. Therefore, results from sensory testing should not be used to decide on a patient’s rehabilitation potential. If appropriate, sensory testing should be performed both before and after a period of intensified sensory stimulation to the most affected body part. Sensory stimulation aims at improving both transmission and the patient’s focus toward the body part that is being treated. An improved focus often implies that the patient’s CNS starts to interpret and integrate sensory information. The therapist should attempt to discriminate whether the sensory problems are organic (sensory pathways) or perceptual, as this is important for therapeutic intervention.

Lesions of the Ascending Systems

It is necessary to have a good sensory perception for discriminative tasks, such as threading a needle. In this case sensory testing may be appropriate. Discrimination requires localization of sensory inputs.

Starting Position

In sitting, the patient should place—or get help in placing—both his hands behind his body with the palms up. In this way he is not able to see what the tester is doing, and tonic influences are often neutralized as the arms are in flexion, adduction, and internal rotation with flexion at the wrists. First the therapist needs to gain a general impression of whether there are differences in superficial sensation between the hands, using her own hand to touch.

Finger Discrimination

Finger gnosis is tested by the therapist touching one finger at a time and asking the patient to name the finger. Recognition of the individual fingers is important for discrimination, and informs the therapist if the fingers have maintained their cortical representation.

• If the patient is aphasic, he may move the same finger on the opposite hand to indicate which one he thinks it is.

• If recognition is weak, but mostly correct, there is some connection to the cortex.

• If there is no recognition, the patient has finger agnosia: the cortical representation of the individual fingers is not aroused.

• The patient may have receptive problems and not understand these instructions, in which case testing like this is inappropriate.

Sensory stimulation may improve this to some level, but the patient’s prognosis for discriminative hand and finger function is poor.

Localization of Touch

Two-point discrimination is performed to test the ability to precisely locate stimuli. The therapist uses two equal and sharp objects (needles or similar) and starts by testing the patient’s index finger, because this finger is most densely packed with sensory receptors. The therapist pricks the patient simultaneously with the two objects. The therapist needs to test for different distances between the two points at different locations on the finger to find where the patient is able to discriminate the two points. The smallest distance for two-point localization is measured for future reference.

Joint Position Sense

The therapist moved the joints of the index finger or the thumb and asks whether the patient can describe the position or copy with the other hand. If he is not able to do so, the therapist may test his wrist and gradually more proximal joints of the arm. It should be noted that this form of testing is very limited:

• Joint position sense depends more on input from active muscles and compression/stretch of skin than joint receptors alone

• Only the patient’s conscious awareness is tested, not how the CNS receives, interprets and integrates the information that it actually receives (see Chapter 1.1 Systems Control, The Somatosensory System), therefore firm conclusions should not be drawn from these results if they are deviant

Conscious awareness of sensory information is more important for hand function than for walking. In people with CNS lesions there is no primary damage to ascending systems at the level of the spinal cord. Sensory impulses are received and integrated to some degree in the spinal cord, and transmitted to the cerebellum and other higher centers. This information may therefore be used for pattern generation and inter-limb coordination through the cerebellum. The patient’s fine tuning of balance will be impaired to some degree if sensory information from the soles of the feet is diminished (Kavounoudias et al. 1998, Meyer et al. 2004).

Perceptual Function

Patients with CNS disorders may exhibit perceptual dysfunctions that cause decreased attention or neglect toward the most affected side. Neglect is obvious in patients who do not turn to the affected side, do not take care of, or dress their most affected extremities, walk or wheel into objects, people, door frames, furniture on the most affected side.

Some patients do not integrate information from the most affected side when they receive information from their less affected side at the same time. The therapist may suspect this form of inattention if the patient has some movement in their most affected arm, but do not attempt to use it. This may be assessed through simultaneous bilateral touch. The prerequisite for performing this test is that the patient does have sensation when the most affected side is tested alone.

Simultaneous Integration

The test is performed in the same testing position as above if possible. The therapist stands behind the patient and touches one arm at a time, asking the patient to say which arm/hand is touched (right or left). At intervals she touches both arms or hands at the same place at the same time. If the patient still only says the less affected side, this implies that information from the most affected side is suppressed, i. e., not integrated. This means that when the patient is in situations that require integration of stimuli from both sides at the same time—in traffic, among people, in many daily situations—he may be in danger of causing damage to himself.

Learned Nonuse

Patients may exhibit sensory problems as a result of inactivity or nonuse. Usually this applies more to the distal body parts, hands, and feet, more than the rest. Learned nonuse may be overcome by stimulating, mobilizing, and facilitating the patient’s activity. If the patient expresses that he can feel his hand or foot better after treatment, this implies that there is a degree of learned nonuse (see Chapter 2, Physiotherapy).

Pain

Pain may limit the patient’s recovery and learning processes and lead to depression, loss of motivation, and social isolation. The patient may experience pain when the arm is being moved for instance during dressing and washing and this may lead to withdrawal from daily activities and treatment and deterioration of functional ability.

Possible Causes

• Increased tone: malalignment and possible fixation of joints in unnatural postures, static activation of muscles and decreased circulation, or sudden pulls (cramps, spasms)

• Trauma: due to poor handling, falls, or instability of joints

• Altered sensory awareness/perception

• Other causes (e. g., disuse over time, swelling, inflammation, degenerative conditions)

The physiotherapist must assess the cause of pain; where the pain is, which situation exacerbates or improves it, and when the patient experiences pain (day, night, during activity, at rest), and thereby get an impression of the causal factors and severity. History and movement analysis (observation and handling) as well as information from other examinations (X-rays, ultrasound, other) and from carers as well as using a visual analogue scale (VAS) may be useful. Pain is always a priority of treatment.

Autonomic Function

A CNS lesion may cause altered autonomic function both locally and more generally. Local changes are present in many patients with CNS dysfunction, and may be caused by dysfunctions in central regulation or as a result of inactivity and immobility. It often manifests itself as a more distal problem, in the hands or feet.

• Altered circulation: the skin color is more bluish, reddish, or pale.

• Changes in temperature follow changes in circulation: the extremity is cold to touch. If the patient has an infection such as vasculitis the area will be warmer and redder.

• Swelling is observed and palpated, and is fairly common in the hand or foot of a patient who has had stroke or has MS. If chronic, it may cause further circulatory-, movement- or pain-related problems. If there is a generalized stiffness and/or swelling in a patient’s leg and/or thigh combined with pain or tenderness, or the pain increases when the foot is dorsiflexed and the big toe extended (Homans sign), the patient has to be examined for possible deep vein thrombosis.

Skin Quality

There may be changes in the skin due to inactivity, immobilization, and decreased circulation. Inactivity may lead to thick and hard skin, and may cause further immobility of the affected area. A hand that is not used becomes drier with increased skin thickness because the dead skin does not rub off during use.

General Symptoms

These are more common in spinal cord injury (SCI), especially complete SCIs. The symptoms may vary in intensity and character:

• Sweating above trauma level

• Increased heart rate

• Headaches

• Increased blood pressure

• Reddened skin

Clinical Relevance

Stroke patients frequently suffer from shoulder or wrist pain, or a combination. In a systematic review by Geurts et al. (2000), both shoulder–hand syndrome (SHS) and post-stroke hand edema are described. Geurts et al. concluded that:

• The shoulder is involved in only half of the cases with painful swelling of the wrist and hand, suggesting a wrist-hand syndrome.

• Hand edema is not lymphedema.

• SHS usually coincides with increased arterial blood flow.

• Trauma causes aseptic joint inflammation in SHS.

• No specific treatment has proved advantageous over any other physical methods for reducing hand edema.

• Oral corticosteroids are the most effective treatment for SHS.

In the author’s experience, careful but persistent mobilization combined with correction of alignment and sensory stimulation may improve this problem.

WHAT? HOW? WHY?

These are the three most important questions in the ongoing assessment of the patient.