Chapter 2 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Discuss the phases and purposes of assessment. 2. Discuss the areas of assessment necessary to evaluate communication. 3. Name and define the properties, strengths, and weaknesses of standardized tests. 4. Discuss methods of assessment that are alternatives to standardized testing. 5. Describe data used and guidelines for making assessment decisions. 6. List approaches for facilitating assessment with the child who is hard to assess. 7. Discuss approaches to integrating and interpreting assessment data. The approach to language evaluation presented in this chapter derives from the work of Jon Miller, Peg Rosin, Gary Gill, and others at the Waisman Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This approach has been developed during the last four decades by these clinicians taking a developmental approach to understanding developmental language disorders (DLDs). Some of the material discussed in this chapter has been drawn from published sources (Miller, 1978, 1981, 1996) but much of it derives from their inspirational teaching and our clinical experiences of using this approach with children and their families. We saw in Chapter 1 that there are different ways of conceptualizing DLD: the naturalist approach, which views DLD as an impairment or disease process within the individual that disrupts functioning, and the normative approach, which focuses more on societal expectations and obstacles to meeting those expectations (Tomblin, 2008). Traditionally, clinicians coming from a medical model would adopt a naturalist approach to appraisal, the collection of data from a variety of sources to describe the client’s condition; and diagnosis, the assignment and labelling of the clinical condition by means of the interpretation of standardized tests, case history information, observation, and medical examination, often with some inference about its underlying cause. From a normative perspective, on the other hand, identification of the problem and its cause are less important than understanding how the impairment influences social and behavioral outcomes for the child. As Tomblin (2008) puts it, “the causes of individual differences (environments, genes, etc.) in language development are different from those that cause us to be concerned about some of these individual differences” (p. 95). In practice, we tend to blend the two perspectives together. The goal is to decide whether the child has a significant impairment in language form, content, and/or use, to describe that deficit in some detail relative to the normal developmental sequence of language acquisition, and to determine how this deficit will affect the child’s daily activities (school, family, and social well-being). Issues of cause or the identification of a disease category are less central to the speech-language pathologist’s (SLP’s) mission, though we should bear in mind that we are often the first port of call for concerned parents or teachers. We should therefore be alert to the need to refer the child on for more detailed medical assessment. The SLP almost never comes to assessment conclusions in isolation. The clinician is always working as part of a team, either with the child’s family and/or teacher, or as part of a larger multidisciplinary team. Each member of the team will have expertise and unique insights into the child’s strengths and needs. Putting this information together provides a more holistic picture of the child, his or her skills and deficits, and priorities for intervention and education planning. The SLP will be the expert in eliciting speech, language, and communication profiles, and answering questions about how an individual’s profile may affect learning and social well-being. This information may be gathered in isolation, or by working collaboratively with other members of the team. Whatever the method, it is important to understand the role of the other team members and recognize the value of their expert contributions to understanding the child’s language disorder. Key people contributing to assessment teams are outlined in Box 2-1. 1. What is the problem, if known, in medical terms? What do other professionals (doctor, teacher, other speech-language pathologist) see as this child’s area(s) of deficit? 2. When did the problem begin, or has the child always had it? Was the onset sudden or gradual? 3. Does the problem vary in severity, getting worse at some times or with some people and better with others, or is it always about the same? 4. How does the social environment interact with the child’s problem? Is the child perceived as failing at school or other important social settings? How does the family see the child and react to the difficulties? Many agencies use a standard intake questionnaire to collect some of these data before meeting with the family. Appendix 2-1 gives one example of this kind of questionnaire that is filled out by a parent before the child’s first meeting with the clinician. Appendix 2-1 also contains a request for release of information. Such a request must be signed by the parent and must be sent along whenever clinicians attempt to solicit information about a child from another agency. When developing an assessment plan it is wise to assemble any information available from other agencies where the child may have been a client. Including a form like this one with an intake questionnaire is usually an efficient way to find out whether the child has been seen by other professionals and to get access to the information they collected. Once background data have been reviewed and key remaining questions have been highlighted, a detailed case history will be helpful in refining assessment plans. Techniques for clinical interviewing are beyond the scope of this chapter, though detailed information is available in the work of Shipley and McAfee (2008). These authors suggest that sensitive interviewing requires mutual respect; making sure that the clients understand the purpose of the interview; listening carefully; asking clear, open-ended questions that are not leading or loaded (e.g., a loaded question might be: “you don’t scold him when he makes mistakes do you?”); and answering any questions posed by the family. Above all, the case history should highlight the family’s major concerns. It is important to remember that parents may not always see language as the primary problem, but may be more concerned about the child’s behavior, social skills, or learning and that these concerns may be related to underlying language difficulties. A case history also provides an opportunity to document any pre-, peri- or post-natal risk factors that may affect language development (e.g., drugs and alcohol, illness, hearing loss) and family history of speech, language, or literacy difficulties. The case history should also be used as a vehicle to elicit from parents clear examples of the child’s communicative attempts, what motivates the child to communicate, how the child communicates, with whom the child communicates, and what he or she does when communication fails. Taking a sample of the child’s communication skills in less formal contexts can also be illuminating. The format of the language sample may depend on the clinical context and potential intervention approaches. For example, with a very young child with suspected autism spectrum disorder (ASD), it may be most appropriate to make a video recording of the child and parent playing together. This will allow the clinician to document how synchronous the parent and child are in their communication; as well as recording the child’s use of gesture, eye contact, communication attempts, vocalizations, and preferred play activities. The clinician may also get a sense of how well parents identify communication attempts, how they respond to these attempts, and how they naturally reinforce gesture and vocalizations with language. For more verbal children, recording a conversation between the child and his or her parents and/or clinician can give insight into articulation accuracy and fluency, diversity of vocabulary, utterance length, and grammatical complexity. Software programs such as the Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (Miller & Iglesias, 2008) allow for automatic calculation of a number of language variables that are useful in distinguishing speakers with DLD from their typically developing peers (Heilmann, Miller & Nockerts, 2010). Language samples have other advantages that make them a useful complement to standardized testing. First, they can be readily used with children from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Although standard metrics are not currently available for all language communities, normative data for speakers of Spanish (Bedore, Pena, Gilliam, & Ho, 2010) and African-American English (Oetting et al., 2010) dialects are being developed. Second, even without these normative data, language samples can be a useful way of documenting change, either over time or in response to intervention (Adams & Lloyd, 2005). Finally, as well as documenting articulation, vocabulary, and grammar, language samples provide a unique opportunity to survey pragmatic language skills in more naturalistic contexts. Aspects of pragmatic language such as turn-taking, initiation, topic maintenance, intonation, and reciprocity can be reliably coded and differentiate individuals with autism spectrum disorders from non-ASD peers, independently of structural language deficits (de Villiers et al., 2007; Paul, Orlovski, Marcinko, & Volkmar, 2008). These pragmatic language skills are difficult to assess using standardized tests, but will be important in formulating treatment plans. In summary, a language sample is a key component of the assessment process as it allows the clinician to gauge how the child uses his or her language for conversational exchange, to assess difficult to measure aspects of language, and can give insights into the skills and difficulties experienced by the child’s primary communication partners. Some of these assessments will be carried out by the speech-language pathologist, while others may require referral to other agencies. In most instances, the clinician will want to confirm that the child does not have a hearing loss that may be contributing to language difficulties, so referral to an audiologist may be necessary. In addition, the clinician needs to determine the child’s general developmental level, as this will influence the level at which to begin a communication assessment. The main question to consider is whether the child’s day-to-day functioning is at or near the level we would expect given the child’s age. If the client is a toddler, does the child walk, feed himself or herself, and so on? As a preschooler, does the child engage in pretend play, drawing, some self-dressing, bathing, toileting, and similar activities? As a school-aged child, is he or she placed in the appropriate grade? As an adolescent or young adult, are daily living skills (cooking, independent travel, social activities) age-appropriate? As we discussed in Chapter 1, communication skills are not usually more advanced than other areas of development, so general developmental level provides a reasonable baseline for beginning to assess communicative performance. If further assessment indicates that language and communication skills are out-of-step with other aspects of development, appropriate adjustments in the plan can be made. The most important thing about an assessment plan, though, is that it be planned. We want to get into the habit of reviewing case history and intake data and using them to make decisions about the most appropriate goals and methods for assessment. We should then write out a plan that includes the goal and methods decided upon for each area being assessed, keeping in mind that we may have to deviate from the written plan if our interactions with the child suggests an alternative course of action. A sample of a form for such a written plan is provided in Figure 2-1. Using this approach, we can ensure that we use the client’s time well in the assessment, and that we will come out of it with the most comprehensive and valid information possible. Westby, Stevens, Dominguez, and Oetter (1996) identified four basic reasons for assessing language performance in a child that still motivate our assessment practices today. Each reason involves somewhat different goals and methods. Let’s talk about each of these assessment purposes. Very often in clinical practice, clients are referred for assessment because someone (usually a parent or teacher) is concerned about the child’s development. This kind of referral suggests it is likely that the child’s problem is interfering with daily activities to such an extent that our help is sought. However, many children who attract clinical attention have multiple developmental concerns or a particular pattern of speech, language, and communication concerns that is obvious to non-professionals, even though it might not be the fundamental problem. For instance, children with speech sound disorders are more likely to be referred for clinical services compared to peers with similar levels of language ability who do not have problems with intelligibility (Bishop & Hayiou-Thomas, 2008). In contrast, problems with language comprehension may be “hidden” and unlikely to be noticed unless accompanied by behavioral difficulties (Zhang & Tomblin, 2000). These children with hidden language impairments are at greatly increased risk for academic failure and, in particular, reading comprehension deficits (Nation, Cocksey, Taylor, & Bishop, 2010), and it would therefore be useful to identify these children earlier in development so that we may intervene before academic problems become entrenched (Clarke, Snowling, Truelove, & Hulme, 2010). In addition to its psychometric properties, a good screening measure should tap a broad range of language and communication functions in the most efficient way possible. If, for example, we used the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—IV (PPVT-IV; Dunn & Dunn, 2006) as a screening instrument, we might learn that a child does not score below our cut-off (e.g., the 10th percentile). Does that mean that the child does not have a language disorder? Not necessarily. A child could have a normal receptive vocabulary and still have a great deal of difficulty with expressive language skills or comprehension of complex syntax. On the other hand, we don’t want to spend significant amounts of time testing children on a full language battery before we know whether they need in-depth assessment. The Children’s Communication Checklist—2 US Edition (CCS-US; Bishop, 2006b) is a good example of a screener that samples a range of language and communication skills for children aged 4 to 16 with a minimum investment of time. The Childhood Communication Checklist—2 US (CCC-2US) asks parents and/or caregivers to rate the frequency of both positive and negative communication behaviors, has excellent psychometric properties, and does a good job of identifying children at high risk of language impairment (Bishop & McDonald, 2009). In evaluating the results of our screening, we need to ask whether a child who appears to have a language problem is demonstrating a linguistic difference or disorder. We need to be aware of this issue for any child who comes from a culturally or linguistically different background, such as the child from a family that speaks Spanish in the home or an African-American child whose family uses a non-standard dialect of English. For those children, whose experiences with English may be different from those of children from mainstream backgrounds, our first decision will be whether the child has a bona fide impairment or a communication problem that results primarily from a mismatch between the child’s experience and the expectations of the social environment. We’ll talk in detail about making this decision in Chapter 5. If a child fails a screening measure, this does not, of course, mean he or she definitely has a developmental language disorder. Screening is used only to identify children at risk of DLD. For children who fail screening, a more extensive assessment will be needed to determine whether they meet eligibility criteria under IDEA legislation. This assessment will incorporate a range of techniques that we will discuss throughout this chapter. A final word of caution is warranted when considering screening. In assessing children from the general population for potential language impairment, there is often potential to identify “false-positives,” or children who fail the screening measure but do not in fact have DLD. We need to be careful not to cause undue concern among parents and educators. However, reviews of screening measures have failed to identify a “gold-standard” measure that has been adequately evaluated in a population study. That’s why universal screening for DLD has not been established (Nelson, Nygren, Walker, & Panoscha, 2006). Generally, apart from screening that takes place for all children as they enter kindergarten, clients will come to us for screening because someone has noticed something is not going quite right in the communicative development. Once the initial screening question has been answered and we have determined that a child is eligible for special services, assessment is used to determine the child’s current, or baseline level of functioning. This purpose is distinct from the screening and evaluation functions and requires the use of different strategies and instruments. To determine baseline function, it is crucial to examine all areas of communicative function, as well as areas related to the child’s ability to use language, such as hearing, cognitive skills, and oral-motor abilities. Establishing baseline function involves finding out not only the areas in which the child is experiencing difficulty, but also identifying areas in which the child is functioning relatively well. This assessment should result in a profile of “strength” and “weakness,” such as the one illustrated in Figure 2-2. We must be somewhat cautious in using this profile, because different tests will have different psychometric properties, and will have been standardized on different populations, making it difficult to directly compare outcomes on different tests. Nevertheless, such profiles can be useful in providing a broad picture of language and communication functioning. Establishing baseline function may require that we look at the child’s communicative behavior in several settings (that is, we may want to know more than how the child uses language in an unfamiliar place, such as the diagnostic clinic, and with an unfamiliar person, such as the SLP). Numerous authors have discussed the importance of context in observing communicative behaviour (e.g., Coggins, 1991; Losardo & Notari-Severson, 2001; Oetting & McDonald, 2002; Nelson, 2010; Westby, Stevens, Dominguez, & Oetter, 1996). This suggests that we cannot assume that one sample of behavior, gathered in the relatively strange clinical situation, tells us everything we need to know about the child’s capacities for communicating. Let’s see what this might mean in practice. These decisions involve identifying the areas in which the child is functioning below expectations for developmental level. Identified areas—whether they are the comprehension of syntax or vocabulary; the expression of words, sounds or sentences, or the use of a range of different communicative functions—would then be targeted for intervention. Using the profile in Figure 2-2, the clinician is likely to target the most delayed areas of language first. When these areas of deficit are remediated to the child’s highest level of communicative performance, then the target would be to improve overall language functioning so that it more closely approximates the level of language expected for the child’s chronological age, or general cognitive abilities, whichever reference point is being used. Let’s see how we might implement this model for a child like the one profiled in Figure 2-3. Second, ongoing assessment is necessary to decide when to dismiss a client from intervention. Just as we need to decide ahead of time on our criteria for identifying a child with a language disorder, it is important to decide ahead of time what criterion will be used for dismissal (Roulstone & Enderby, 2010). As with so many other issues in our field, there are no clear mandates for discharging clients from speech-language services. Nelson (1998) suggested posing the following questions to determine whether a client is ready to be discharged from intervention: To answer that last question, it will be necessary to understand what our clients and their families feel about the intervention process. Although a child may not have age-appropriate language skills, there may come a time when therapy sessions interfere with other activities (sports, dating) to the extent that the child would prefer to be discharged from therapy. Other reasons to discontinue intervention have been proposed by Fey (1986) and include: 1. The child has reached all the goals identified in the diagnostic phase of the program and is no longer viewed as having a developmental language disorder. 2. The child has reached a plateau and efforts to modify the intervention program do not achieve more progress. 3. The child is making progress, but this progress cannot be attributed to the intervention program. The answer to the question “what shall we assess?” may seem simple. We assess language. But you will remember from Chapter 1 that there is a bit more to it than that. We want to ensure that our assessments will include measures of language form, content, and use. We will also want to consider these domains of language in at least two different modalities: comprehension and production. In typical development language comprehension and production develop in tandem, but they can sometimes come apart in DLD. We therefore cannot make assumptions about one on the basis of the other. Once we’ve established that the child has language difficulties, we need to assess other aspects of development that may affect language functioning or that may need to be taken into consideration when planning intervention. These collateral areas include, at a minimum, hearing, oral-motor functioning, general cognitive abilities, and social functioning. Let’s consider these assessment challenges in turn. 1. Form (syntax, morphology, phonology): Inflectional marking of words (plural –s; past tense –ed; third person singular –s); basic sentence components such as noun, verb, prepositional, adverbial phrases; sentence types, such as negatives, interrogatives, embedded clauses, and conjoined utterances. Form also includes the ability to produce sounds accurately, the consistency of sound production, and the use of phonological simplication processes. 2. Content (semantics): Knowledge of vocabulary; the ability to express and understand concepts about objects and events; the use and comprehension of semantic relations among these objects and events; understanding of lexical ambiguity and multiple meanings (e.g., that “cold” can refer to temperature, illness, or a personal quality). 3. Use (pragmatics): The range of communicative functions (reasons for talking); the frequency of communication; discourse skills (turn-taking, topic maintenance and change, requests for clarification); the flexibility to modify language for different listeners and social situations; the ability to convey a coherent and informative narrative. Chapman (1978), Miller and Paul (1995), and Milosky and Skarakis-Doyle (2006) discussed the differences between children’s performance on comprehension tasks that are contextualized, in the presence of familiar routines and nonlinguistic cues, and those that are decontextualized. They pointed out that children function quite differently in terms of their comprehension performance in these two settings. For example, a child with DLD may be able to follow a 3-part verbal instruction such as, “put your books away, get your coat, and line up by the door” in the classroom, because they can observe what their peers are doing and follow their actions. That same child may struggle to follow a similar instruction in a standardized test (e.g., “touch the ball, then touch the star before you touch the house”). Standardized tests measure decontextualized language comprehension, and reflect the child’s language abilities under the most challenging circumstances. As an adjunct to formal comprehension testing, it can be useful to assess the child’s responses in more familiar, contextualized situations. Miller and Paul (1995) suggested pairing traditional comprehension assessment with assessment of language comprehension in more naturalistic settings with nonlinguistic supports such as gesture, gaze, and other contextual cues. Comparing performance in these two settings can produce a fuller picture of the child’s understanding. Regardless of the assessment setting, it is always important to remember that comprehension is, as Miller and Paul (1995) put it, a private event, something that happens within the child’s mind. We can only make inferences about the child’s comprehension based on the behavioral responses to our questions and probes. If a child responds as expected, we can infer that he or she has understood the construct we are assessing. If he or she gives an incorrect response, we cannot be sure that they have not understood us; children may fail a comprehension item for many different reasons. For instance, they may have forgotten the verbal instruction, they may not have been paying attention to what we said, they may not be able to hear what is being said, or they may choose not to comply with our assessment. We therefore need to understand the additional demands of different language assessments and choose our measures wisely, so that our inferences about comprehension are as valid as possible. We’ll talk more about this in the “How to assess” section. Unlike assessment of comprehension, assessment of language production gives us direct access to how children express themselves with language. Tests that require children to repeat sentences of increasing length and complexity can be very sensitive markers of language impairment (Conti-Ramsden, Botting, & Faraher, 2001). But just as children perform differently on comprehension tests in different contexts, they may also produce language differently in different contexts. We therefore need to ensure that in addition to our standardized measures, we sample spontaneous speech in naturalistic settings in order to determine functional and ecologically valid targets for intervention. As big as the job of assessing language function may seem, it is not the whole task of conducting an assessment. In addition to analyzing all these aspects of language, a thorough assessment also involves investigating collateral areas that relate to the child’s communicative function. The SLP may not gather all this information single-handedly. In a multidisciplinary team, other professionals may provide some of the necessary data. But even if the evaluation is conceived of as a circumscribed language assessment, it will be necessary to get this information. Upon completing the speech, language, and communication portion of the assessment, the SLP may need to request additional information from other professionals. This can be done by referring the child for further testing (Appendix 2-2). No language assessment is complete without an investigation of the child’s hearing status. Many SLPs screen children for hearing impairment, using small, portable audiometers specifically designed for this purpose. The American-Speech-Language Hearing Association (1997) has set guidelines for this screening. More recently, otoacoustic emissions testing has been introduced as a screening method (Hof, van Dijk, Chenault, & Atenuis, 2005). Children who fail either of these screenings need to be referred for comprehensive audiometric assessment. Assessing the speech-motor system consists of examining facial symmetry; dentition; the structure and function of the lips; tongue, jaw, and velopharynx; and respiratory, phonatory, and resonance functions as they are used for speech. Bukendorf, Gordon, and Goodwyn-Crane (2007) and Shipley and McAfee (2008) provide some guidance in interpreting the oral-facial examination. McCauley and Strand (2008) provide a review of standardized measures for assessing oral-motor functions. Figure 2-4 provides a form that can be used to guide this assessment, derived from Meitus and Weinberg (1983) and Spriestersbach, Morris, and Darley (1991). The form is used by observing each element outlined on the checklist and marking either yes or no for each observation on the form. At the end of each section, a judgement of the adequacy of the structures and functions for speech is made. The overall ratings to be made are: 2. Slight deviation; probably no detrimental effects on speech 3. Moderate deviation; possible effect on speech, especially if other structures are also deviant 4. Extreme deviation; sufficient to interfere with normal production of speech, modification of structure required The face can be examined from a frontal view to determine alignment; spacing of the eyes; proportions of the face; and symmetry of the nares, philtrum, and Cupid’s bow. The clinician can observe whether the lips approximate at rest, whether they retract symmetrically when the client smiles or produces /i/, and whether they contract symmetrically when he or she produces /u/. Details for making these observations are provided in Figure 2-4. Normal appearance and terminology for this examination are given in Figure 2-5. Observing the face in lateral or profile view, the clinician examines the alignment of the facial features again, using the guidelines in Figure 2-4. This observation can be conducted on a client of any age, including an infant. The functional integrity of the facial musculature can be observed by asking the client to raise the eyebrows, to close the eyelids against the resistance of the clinician’s finger holding them open, and to smile and frown. Resting posture of the face can be observed for symmetry. Movement and proportions of the mandible also can be evaluated, as outlined in the form in Figure 2-4. A developmental level of 24 months is necessary for the child to perform these assessments. Even a 2- or 3-year-old child may have difficulty with some of these activities, though. Young children will probably need to imitate these movements rather than produce them on verbal request. Asking the child’s mother or father to imitate the clinician first and then have the child do so may be useful. Suggesting that the child pretend to be a clown making funny faces can help; so can using a mirror so that the child can see the funny faces being made. Face painting may also facilitate this assessment, but check with parents first. When conducting an intraoral examination, surgical gloves must be worn for the safety of the clinician as well as the child. Alignment of the teeth (normal appearance and terminology are given in Figure 2-6) and the occlusion of the mandible can be assessed using the guidelines in Figure 2-4. The eruption, spacing, and orientation of the teeth and the structure and proportion of the tongue also can be observed. Movement of the tongue can be encouraged by using a lollipop and asking the child to lick it as you place it above, below, and on either side of the child’s mouth. Be sure to let the child have the lollipop when you complete the assessment, though! The structure of the hard palate can be examined using a small penlight, noting the features in Figure 2-4 with reference to the model given in Figure 2-7. The clinician should be especially alert for signs of a submucosal cleft of the palate (Figure 2-8) and the presence of a bifid uvula (Figure 2-9). These signs include a whitish appearance of the soft palate and a depression in that area that can be felt on palpating the velum. To palpate the velum, stand behind the child with his or her head resting against you as you move a gloved finger along the midline of the palate from the alveolar ridge to the velum. These findings would indicate the need for further evaluation of the velopharyngeal structures. The function of the velum can be observed by asking the child to sustain /a/ and then to produce short repetitions of /a/-/a/, as indicated in Figure 2-4. Even if the velopharyngeal structures appear normal on inspection, it is wise to assess the child’s ability to use the velopharyngeal port in speech activities. This can be accomplished quite easily with two quick and efficient instruments. The Iowa Pressure Articulation Test (IPAT; Morris, Spreistersbach, & Darley, 1961) was developed to assess speech errors often associated with velopharyngeal insufficiency. This procedure can be used with children at developmental levels as low as 24 to 30 months. The words used for this test are shown in Figure 2-10; the phonemes within these words that are most important for assessing velopharyngeal function are underlined in the box. The clinician merely asks the client to repeat the words and notes whether the underlined segments are produced correctly. If so, a check is placed on the line for each word. If not, the type of error is recorded, using the key at the bottom of the box. If nasal emissions, glottal stops, pharyngeal fricatives, or nasal snorts are heard, the function of the velopharyngeal port is likely to be compromised. In this case, further investigation as to the cause of this problem should be undertaken with medical consultation. Even if no structural defects can be found, a child producing errors indicating velopharyngeal insufficiency will need treatment for these errors, as well as any necessary language programming. The degree of perceived hypernasality of speech and the absence or alteration of “pressure” consonants can be evaluated using procedures included in the Great Ormond Street Speech Assessment (GOS.SP.ASS; Sell, Harding, & Grunwell, 1999), an assessment specifically designed to assess velopharyngeal integrity. The sentence elicitation procedure involves asking the child to repeat sentences with a controlled number of nasal sounds. Sentences introduced by Van De Mark (1979) that can be used for this purpose are given in Box 2-2. The sentences vary in the number of nasal sounds included and can be used to determine whether the nasality of these sounds “spills over” to other words in the sentences. Sentences also include plosive stops that require closure of the palate for successful articulation. Atypical distortions of these consonants can be an indication of velopharyngeal insufficiency. A developmental level of about 36 months is required to perform this task. Errors are transcribed and any qualitatively atypical speech errors should prompt structural examination. If no structural abnormalities are found, speech targets for intervention could include making oral-nasal distinctions and producing plosives in connected speech. Looking at oral-motor performance in nonspeech activities can be helpful in deciding whether poor speech is related to poor tone or voluntary control of the oral musculature. Activities that can be used in this assessment appear in Box 2-3. Most children should be able to imitate most of these movements by a developmental level of 36 months. A comparison of spontaneous and imitative oral-motor movements can be helpful in considering different diagnoses and clinicians should be alert to potential differences. Diadochokinetic activities can be used to observe the rate, pattern, and consistency of production of syllables. The smoothness and accuracy of the syllables produced during diadochokinetic productions can be noted by the clinician on the form in Figure 2-4. In addition, diadochokinetic rates can be tested in preschool children using the procedure by Williams and Stackhouse (2000) presented in Table 2-1. In this procedure the clinician instructs the child to “see how fast you can say these sounds.” After a demonstration and practice producing some syllables rapidly, the child is asked to rapidly repeat single syllables, such as /pΛ//pΛ//pΛ/, syllable sequences /pΛ/ /tΛ/ /kΛ/ or multi-syllabic words such as “buttercup” or “patacake.” For young children, accuracy (the number of phonemes correct) and consistency of productions across repeated items may be more informative measures of competence (Williams & Stackhouse, 2000). For older children, rate is the most frequent measurement of DDK performance (Williams & Stackhouse, 2000), in this case the time taken to produce five repetitions of the target sequence. For older children, Fletcher (1978) provided average repetition rates per second, with standard deviations, for ages 6 through 13 years. These appear in Table 2-1. Table 2-1 The Fletcher Time-by-Count Test of Diadochokinetic Syllable Rate

Assessment

General principles of assessment for suspected developmental language disorder

Case history

Language or communication sample

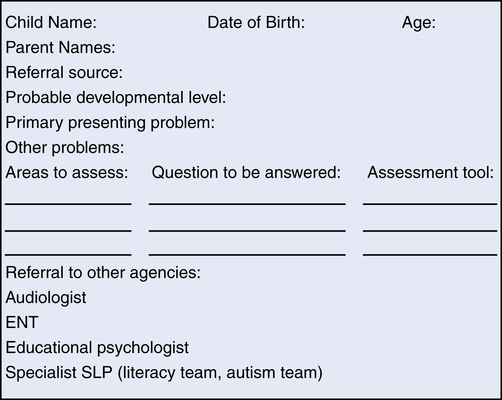

The assessment plan

Why assess?

Screening

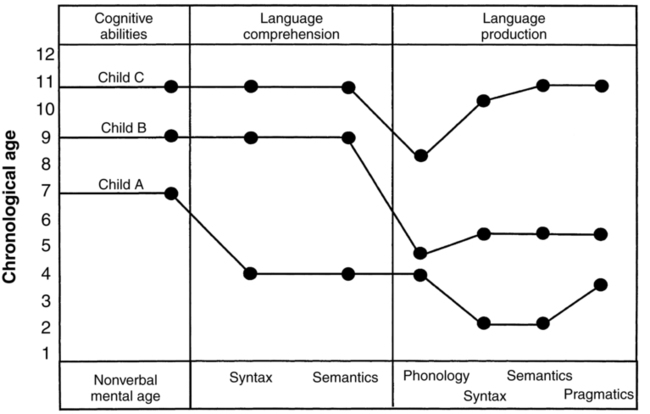

Establishing baseline function

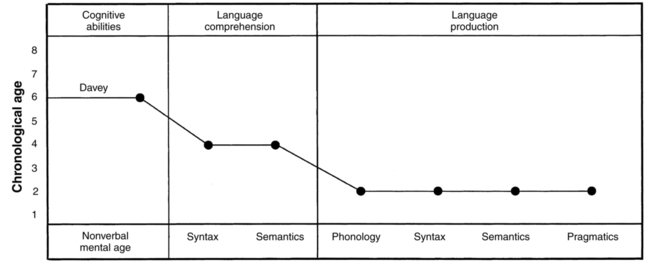

Establishing goals for intervention

Measuring change in intervention

What to assess

Domains of language: form, content, and use

Modalities of language: comprehension and production

Assessing collateral areas

Hearing

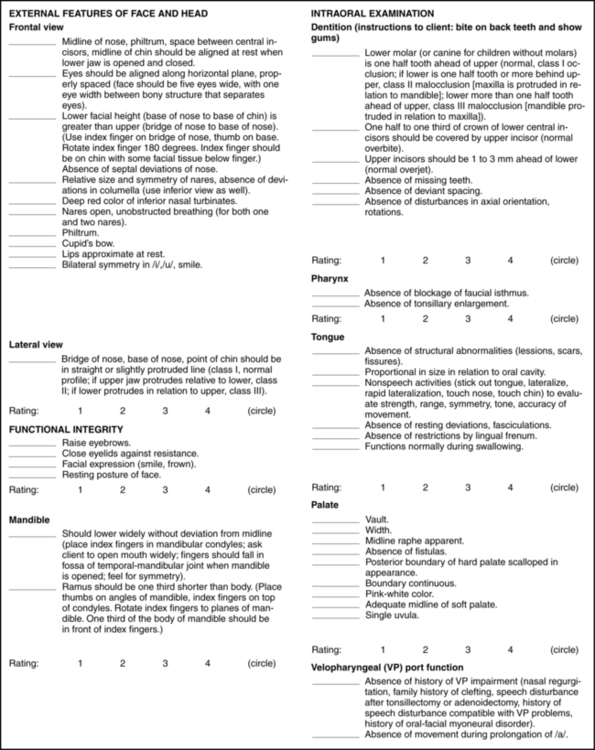

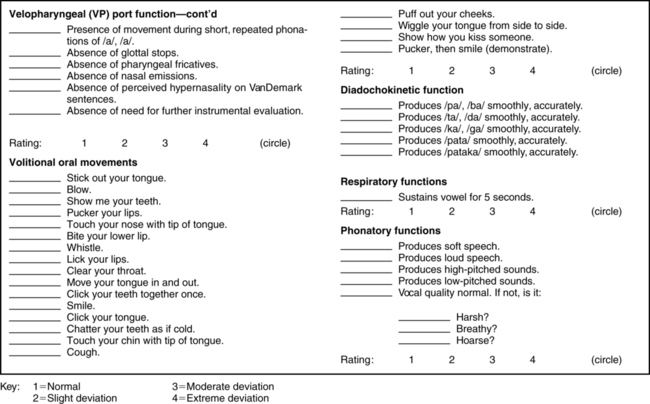

Oral-motor assessment

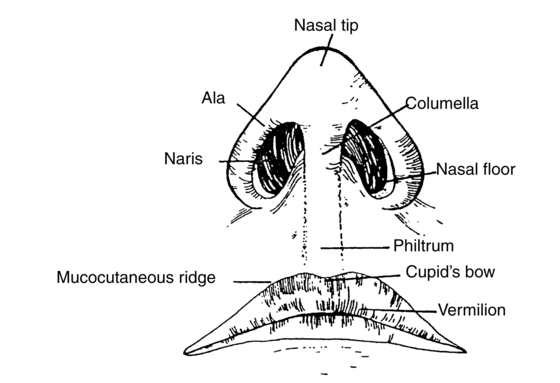

Examination of the external face and head

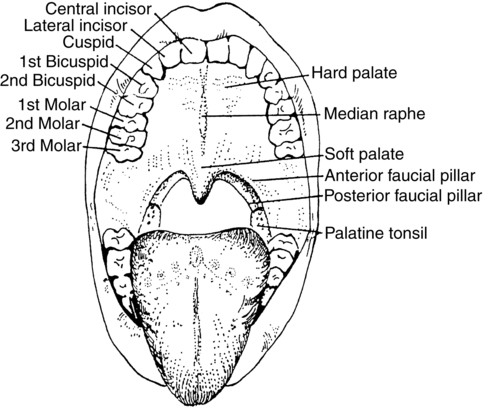

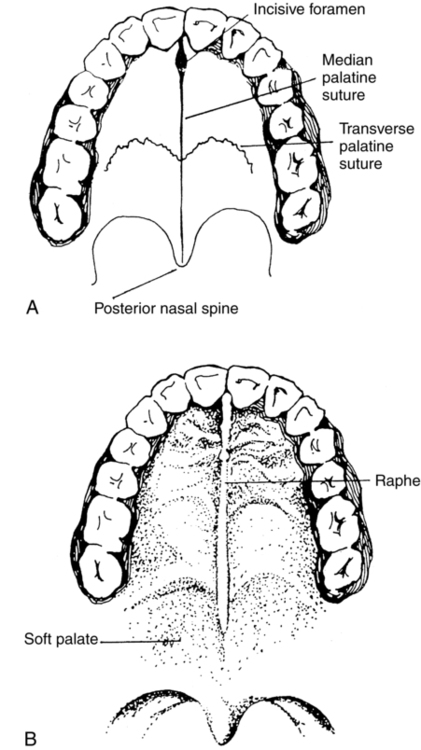

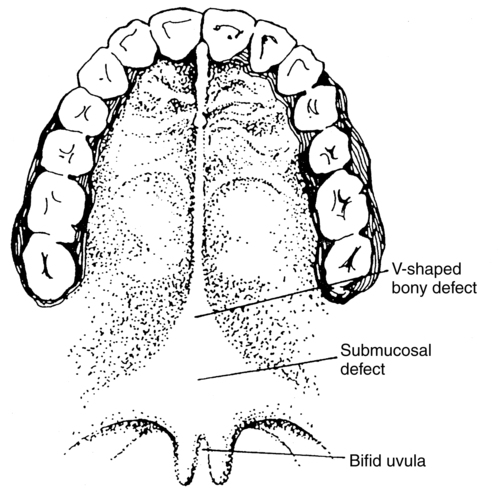

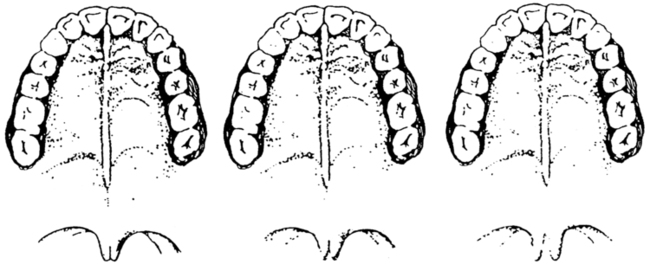

Intraoral examination

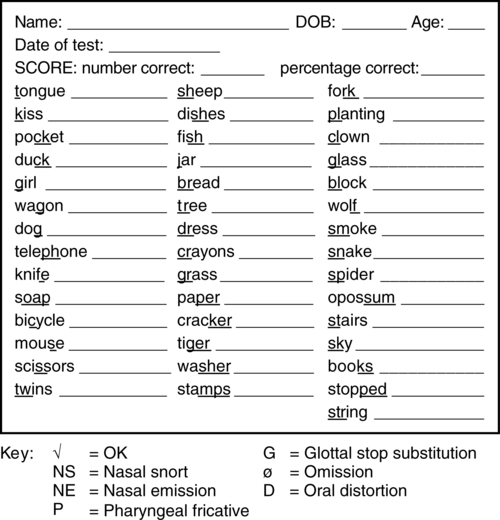

Examination of velopharyngeal function and resonance

Examination of volitional oral movements

Diadochokinetic assessment

Name: _______________________________________________ Date:___________________________________________________________________

B.D.:______________________ Age:_________________ Examiner:____________________________________________________________________

Syllable

Repetitions

#Seconds

Norms By Age (In Seconds)

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

PΛ

20

__________

4.8

4.8

4.2

4.0

3.7

3.6

3.4

3.3

tΛ

20

__________

4.9

4.9

4.4

4.1

3.8

3.6

3.5

3.3

kΛ

20

__________

5.5

5.3

4.8

4.6

4.3

4.Q

3.9

3.7

fΛ

20

__________

5.5

5.4

4.9

4.6

4.2

4.Q

3.7

3.6

lΛ

20

__________

5.2

5.3

4.6

4.5

4.2

3.8

3.7

3.5

STANDARD DEVIATIONS ACROSS SYLLABLES

1.0

1.0

0.7

0.7

0.7

0.6

0.6

0.7

pΛtΛ

15

__________

7.3

7.6

6.2

5.9

5.5

4.8

4.7

4.2

pΛkΛ

15

__________

7.9

7.6

6.2

5.9

5.5

4.8

4.7

4.2

tΛkΛ

15

__________

7.8

8.0

7.2

6.6

6.4

5.5

5.5

5.1

STANDARD DEVIATIONS ACROSS SYLLABLES

2.0

2.0

1.6

1.6

1.6

1.3

1.3

1.3

pΛtΛkΛ

10

__________

10.3

10.0

8.3

7.7

7.1

6.5

6.4

5.7

STANDARD DEVIATIONS ACROSS SYLLABLES

2.8

2.8

2.0

2.0

2.0

1.5

1.5

1.5 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Katie was an 8-year-old girl who had been identified as language/learning disabled by her school learning disabilities specialist and SLP. Her teacher noted that she had a great deal of trouble learning to read and write and that her oral language often seemed disorganized and hard to follow. Although the school personnel did an in-depth assessment, her parents felt they wanted to know more about Katie’s problem and took her to a diagnostic clinic at the state university’s research hospital, about 60 miles from their hometown, for a multidisciplinary assessment. At her first appointment, Katie was given a hearing test, some blood was taken for genetic testing, and extensive cognitive and psychoeducational testing was completed. In the last 2-hour-period of the day, Katie went to the communication disorders section for language testing.

Katie was an 8-year-old girl who had been identified as language/learning disabled by her school learning disabilities specialist and SLP. Her teacher noted that she had a great deal of trouble learning to read and write and that her oral language often seemed disorganized and hard to follow. Although the school personnel did an in-depth assessment, her parents felt they wanted to know more about Katie’s problem and took her to a diagnostic clinic at the state university’s research hospital, about 60 miles from their hometown, for a multidisciplinary assessment. At her first appointment, Katie was given a hearing test, some blood was taken for genetic testing, and extensive cognitive and psychoeducational testing was completed. In the last 2-hour-period of the day, Katie went to the communication disorders section for language testing. Davey is a 6-year-old boy being evaluated for language deficits after failing a kindergarten screening. Comprehensive evaluation indicated that Davey was functioning at age-appropriate levels on measures of nonverbal cognitive ability. His receptive syntax and vocabulary scores were below the 10th percentile for his age, with age-equivalent scores of around 4 years. Expressive language was below the second percentile on all standardized measures. In addition, language sampling showed infrequent expression of communicative intentions and sentences were limited to telegraphic utterances with few grammatical morphemes. Most expressive skills were on the 2-year level. Davey’s parents were initially unconcerned, as they were able to anticipate what he was trying to say and he didn’t seem frustrated by his limited language skills. However, as he was now in school they were increasingly noticing that he was not as talkative as his classmates. Davey’s teacher confirmed this and reported that his limited language often meant he was isolated and did not have as many playmates as the other children.

Davey is a 6-year-old boy being evaluated for language deficits after failing a kindergarten screening. Comprehensive evaluation indicated that Davey was functioning at age-appropriate levels on measures of nonverbal cognitive ability. His receptive syntax and vocabulary scores were below the 10th percentile for his age, with age-equivalent scores of around 4 years. Expressive language was below the second percentile on all standardized measures. In addition, language sampling showed infrequent expression of communicative intentions and sentences were limited to telegraphic utterances with few grammatical morphemes. Most expressive skills were on the 2-year level. Davey’s parents were initially unconcerned, as they were able to anticipate what he was trying to say and he didn’t seem frustrated by his limited language skills. However, as he was now in school they were increasingly noticing that he was not as talkative as his classmates. Davey’s teacher confirmed this and reported that his limited language often meant he was isolated and did not have as many playmates as the other children.