53 Assessment and Avoiding Complications in the Scoliotic Elderly Patient

KEY POINTS

Introduction

Scoliosis — defined as a curvature of the spine in the coronal plane measuring over 10 degrees — can be found in the adult population and can be a significant source of disability, especially in the elderly.1,2 There are three principal forms of scoliotic spinal deformity that can be described: idiopathic, i.e., that whose development can be found during the juvenile or adolescent growing years of life and which persists into adulthood; de novo, which involves the development of a new scoliosis later in life as a result of degenerative changes in the lumbar spine; and osteoporotic scoliosis, a less common form of spine curvature secondary to osteopenic collapse of vertebral bodies.

In the adolescent with scoliosis, the primary focus of treatment is the deformity and concerns of curve progression. In the older patient, it is much more common that pain is the primary complaint.3,4 In the later decades of life, curve progression becomes less and less of a concern, primarily because of the restraint provided by the degenerating and ossifying disc spaces and the arthritic facet joints. Being out of balance, especially in the sagittal plane, adds an element of posturally related fatiguing pain that limits patients’ ability to perform upright activities.5 Older adults are most commonly symptomatic in the lower thoracolumbar or lumbar region, due to the age-related disc degeneration and osteoarthritis associated with the deformity.

Surgery

Elderly patients undergoing surgery for scoliosis face the prospect of increased morbidity and mortality compared with their younger counterparts, primarily because they enter into the surgery much more disabled and with worse health status.6–8 In the preoperative assessment, careful attention should be paid to their cardiac and pulmonary systems, as many patients have become quite sedentary and the stress of surgery may thus become problematic. If patients smoke, they should be encouraged to quit at least a number of weeks before the operation, not only to improve the chances of bone healing but to lessen the likelihood of pulmonary and wound complications, which are already elevated in the elderly population. If there is a suspicion of respiratory compromise, a history of smoking, or planned procedures about the diaphragm, preoperative pulmonary function should be assessed.

Similarly, if elderly patients have a history of cardiac or ischemic disease, they should undergo preoperative stress testing and formal cardiac evaluation. It is recommended that the elderly who have concomitant diagnoses of either hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes be considered for perioperative beta-blockers.9

Elderly patients may have become relatively malnourished and the associated risks of sepsis, wound breakdown, etc., are well established.9 Total parenteral nutrition should be considered in staged surgical treatments, as it has been shown to diminish the rate of nutritional depletion and postoperative infections.

Surgical Techniques

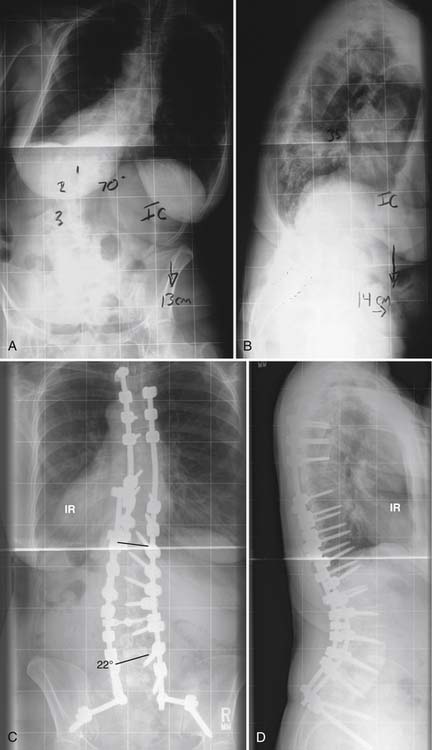

Unlike in the adolescent, where maximal safe correction of the coronal plane curvature is sought, in the elderly, aside from obtaining a solid arthrodesis, much more critical than Cobb angle correction is the obtaining and maintenance of appropriate balance in both the coronal and sagittal planes. A stable and balanced spine is the principal goal of deformity surgery in the elderly, and this often involves accepting less curvature correction. Numerous studies have emphasized that the component of postoperative radiography most closely tied to overall clinical success is the achievement of adequate balance, especially in the sagittal plane. Glassman and other members of the Spine Deformity Study Group, in a review of nearly 300 patients, have suggested that restoration of the normal sagittal balance is the most critical goal for any reconstructive spine surgery.5 A plumbline dropped from C7 should fall in the middle of the sacrum in the coronal plane and within the disc space of the lumbosacral articulation in the lateral view. Older adults have typically developed pronounced disc degeneration and narrowing, which leads to a loss of the normal lumbar lordosis and a forward drift of the sagittal plumbline. Osteopenic compression-type fractures can worsen the sagittal alignment, as can any thoracolumbar kyphosis.10 For these reasons, fusions of primarily lumbar pathology may well need to be extended proximally into the upper thoracic spine.

With the increased use of pedicle-screw fixation and advancing techniques such as vertebral resections, the majority of surgery in the elderly is performed through the posterior approach.11 This would even include access to the anterior column, e.g., the intervertebral discs via posterior or transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF or TLIF, respectively). Interbody support at the lumbosacral junction within at least the lower two spaces, L4-5 and L5-S1, is biomechanically mandatory for successful fusion rates.12–14 Support here lessens the strain seen on the posterior instrumentation and protects to a certain degree against pull-out failure. As a general rule, but especially in the elderly, instrumentation should be used to maintain correction, not obtain correction.

Pedicle screws have become the primary method of fixation in deformity surgery, including the elderly, although their bone quality still remains a concern. Pull-out strength of pedicle screws in patients with normal bone density is typically about 1400 N; however, in patients with osteoporosis, the strength can be as low as 200 N.15 Fixation strength of pedicle screws has been correlated with insertional torque. Hence, it is recommended that, in order to obtain some purchase with the inner cortical wall of the osteopenic pedicle, the largest-sized screw that can comfortably be placed be chosen. This is another reason for careful assessment of preoperative computed tomography with measurement of the inner diameters of the pedicles. In settings of reduced purchase quality, many surgeons treating the elderly may reinforce pedicle screws with adjacent laminar hooks or sublaminar wires. Of note, in the elderly spine, compared with younger adolescent patients treated for scoliosis, the transverse processes are typically quite brittle, and, with few exceptions, are not commonly recommended as points of principal fixation for instrumentation such as hooks.

Fixation into the sacrum is a particular problem as the quality of the bone is probably the poorest here, and the risk of fusion failure (pseudarthrosis) may be one of the highest.16,17 This is another reason why combined anterior and posterior surgery is recommended for long fusions down to the sacrum or the ilium: at a minimum, L4-5 and L5-S1 require strong structural support. In addition, because of the risk of osteopenic fracture of the sacrum when long fusions extend distally, supplemental iliac fixation is highly recommended (Figure 53-1).18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree