Illustration of the importance of targeting intervention appropriately

It is also worth considering the use of a discrete, structured program of a trial intervention: working with a family over a period of weeks enables an accurate assessment of the parent’s capacity to change. The Parent–Child Game (e.g., Forehand and McMahon, 1981) is one example of a short-term, focused behavioral intervention for parents with strong-willed young children. It can also assist parenting assessment by providing a baseline measure, a circumscribed short piece of work, and a repeat measure that indicates whether change is possible.

Formulation of parenting

Completing a comprehensive assessment with a family often generates a large amount of complex “data” that can feel overwhelming. The aim of a formulation is to structure and integrate this information and develop a coherent narrative that identifies avenues for intervention.

Box 1 gives an overview of the dimensions that need to be explored when conducting a parenting assessment and formulation.

1 Focus on role of parent

a. capacity to attend to child’s physical, intellectual, social, and emotional needs; capacity to provide a stable and nurturing environment (secure base)

b. age-appropriate understanding and expectations of child, including the capacity to talk with child about parent’s mental illness

c. capacity to initiate or follow, and enjoy child-centered activity (play)

d. capacity to protect child (evidence of risk in wider system).

2 Focus on the impact of mental illness on role of parent

a. sense of responsibility for self, child, and family

b. level of disturbance, instability, and violent tendencies (impulse control)

c. behavior and psychiatric symptoms directly affecting parenting capacity, including alcohol/drug addiction

d. level of paranoia/capacity to form trusting relationships

e. level of insight and capacity to reflect on own experiences and impact on self and relationship with child

f. attitude to social and cultural norms/relationship to society

g. role of mental illness in risk to child and in risk to parent–child relationship.

3 Focus on role of child

a. capacity for self-protection and resilience

b. developmental progress and child’s mental health

c. child’s attachment strategies. Unusual behaviors and characteristics (non-child-like)

d. relationships outside the nuclear family, including extended family, peers, and school

e. involvement in parent’s symptoms or substance misuse

f. parentification/role reversal.

4 Focus on role of other parent and/or current partner

a. commitment to maintaining the family or commitment to relationship with the child

b. capacity to be available/intervene on child’s behalf if and when necessary

c. attitude to mental health of partner

d. personal health and emotional resources

e. ability to communicate and capacity to work together as parents

f. patterns, style, and intensity of relationship conflict.

5 Focus on context and extended family

a. access to relationship with an adult who is committed to providing support and care for child and/or parent

b. degree and patterns of support from extended family and community, directly to children as well as to parent

c. parents’ relationship to own parents and role of grandparents in child’s life

d. environmental stress/life events/psychosocial stressors

c. cultural expectations of family and parenting within extended family and community.

6 Focus on the role of external support

a. attitude to professionals; use of help and clinical interventions

b. ability to identify own needs and seek support from others as appropriate

c. motivation and ability to use help/clinical interventions to improve family functioning and individual well-being

d. availability of appropriate support structure.

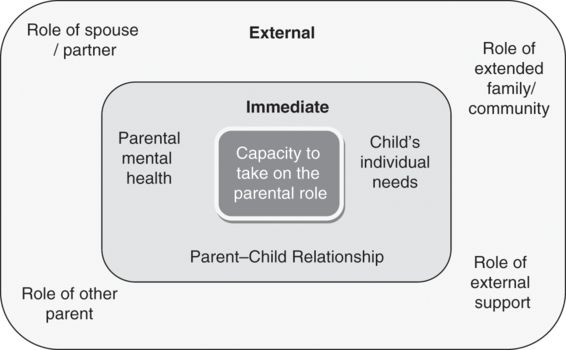

Figure 7.2 highlights the interactive nature of these dimensions – with the parent’s ability to fulfill the parental role dependent on a constellation of factors over and above their experience of symptoms. In many ways this model is similar to that of Nicholson and Henry (2003) presented in Chapter 1 of this volume – but, importantly, our emphasis is on the impact of parental mental health (among other factors) on the ability to perform the parental role specifically. The task here is to develop a functional formulation – that focuses on interpersonal processes rather than on symptoms – in order to guide treatment planning.

Diagrammatic representation of parenting dimensions: factors affecting the capacity to take on the parental role.

A formulation that might result from such an assessment

Jean is a 43-year-old woman who has experienced mental health difficulties since her teenage years. She has been given a diagnosis of psychotic depression but she also experiences periods of extreme anxiety. Jean has a long-standing history of difficulties in close relationships, including those with parents (Box 1, 5c), and her two marriages were characterized by emotional volatility and domestic violence (Box 1, 4f). She has access to some support (involved parents and mental health professionals) but has lost contact with friends and often struggles to maintain trusting relationships (Box 1, 2d), making her formal and informal support network a patchy one.

Jean’s two children have marked individual needs (one is anxious, one is overactive (Box 1, 3b)), posing challenges for Jean. Their behavior acts as a trigger for Jean’s anxiety and low mood. We might hypothesize a “vicious cycle” whereby the children’s emotional responses raise Jean’s levels of arousal and anxiety, making it difficult for her to understand and respond sensitively (and therefore increasing the likelihood of escalation, Box 1, 1a).

While she is committed to meeting her children’s needs, Jean cannot always identify the extent of these needs (Box 1, 1b). She needs help with this and with aiding her children to understand her own mental health problems (Box 1, 2e). There are current gaps in the continuity of her mental healthcare, which may result in her experiencing her own needs as being unmet (Box 1, 6b). This may reinforce her difficulty with trust and with identifying appropriate sources of support and safety within relationships (Box 1, 6d).

In spite of these challenges, Jean has worked hard to try to protect her children from danger and to support them when they feel vulnerable (Box 1, 2a/1d). She has shown some understanding of the potential impact of her own mental illness on the children’s well-being (Box 1, 2e) and a willingness to seek alternative sources of support – from psychiatric services and school-based parenting interventions (Box 1, 6a) to friends and extended family. This suggests that she may be in a position to make use of further services as long as they are appropriately tailored.

For Jean to be able to effectively take on the role of parent, she needs to take care of her own mental health needs (medication, psychotherapy, and wider relational stability) and to better understand her children’s individual needs. Intervention might therefore need to be targeted at a number of levels, providing first for Jean’s own needs and subsequently supporting her in developing an understanding of her children and becoming more responsive to their needs. Importantly, in the interim, this might also involve providing a package of support to the children to ensure that their needs are being consistently met.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree