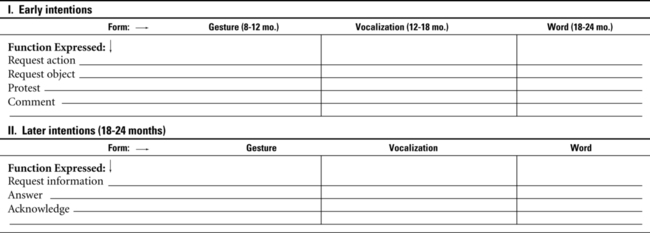

Chapter 7 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Discuss the principles of family-centered practice for toddlers. 2. Describe the communication skills of typical toddlers. 3. Discuss methods of screening, evaluation, and assessment for emerging language. 4. Describe strategies for using assessment information in treatment planning at the emerging language stage. 5. List appropriate goals, procedures, and contexts for treatment of children at the emerging language stage. 6. Discuss the issues relevant to communication programming for older, severely impaired clients with emerging language. 7. List assessment and treatment issues for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Remember that when we discuss children at this beginning language level we mean children whose developmental level is 18 to 36 months. Some toddlers who do not talk, particularly those identified as at-risk during infancy, will not yet function at this developmental level. Using the general developmental assessment tools outlined in this chapter, a toddler’s developmental level can be described. When developmental assessment indicates that a child is functioning below a 12- to 18-month level, even if he or she is chronologically older, management should continue to follow the guidelines given in Chapter 6. Only when general developmental level reaches 18 months or so should the direct communication intervention that is discussed in this chapter be considered. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) 2004 provides for the development of programs for infants and toddlers with disabilities, as we saw in Chapter 6. One of the intents of this law is to affect both primary and secondary prevention by allowing children with disabilities to be identified as early as possible and to receive prompt intervention. Evaluations of early intervention efforts, such as Camilli et al. (2010); Guralnick (1997); McLean and Cripe’s (1997); the National Research Council (2001); and Reynolds, Want, and Wahlberg’s (2003) comprehensive reviews, have concluded that early intervention is effective, often resulting in faster gains than those seen in normal development, so the justification for intervening in these cases is quite compelling. The law’s impact on clinical practice for speech-language pathologists (SLPs), then, is that more and more children younger than 3 are being identified and referred for communication evaluation, assessment, and intervention. SLPs employed in a variety of settings—in hospitals, schools, nonprofit agencies, and private practice—will be seeing this birth-to-3 population. In recent years, several screening instruments have been developed and refined to help clinicians make a general determination about whether further evaluation for communication is needed. Two parent-report measures, which focus primarily on vocabulary size, have been prominent. The MacArthur-Bates Communication Development Inventory (CDI) (Fenson et al., 2007) has been shown in a variety of studies (e.g., Girolametto, Wiiigs, Smyth, Weitzman, & Pearce, 2001; Heilmann, Weismer, Evans, & Hollar, 2005; Lyytinen, Eklund, & Lyytinen, 2003; Weismer & Evans, 2002) to be effective in identifying toddlers with low language skills, and to be valid for both English- and Spanish-speaking toddlers (Marchman & Martinez-Sussman, 2002). The Language Development Survey (LDS; Rescorla, 1989) has also been shown to be valid, reliable, sensitive, and specific for this purpose (Klee, Pearce, & Carson, 2000; Rescorla & Achenbach, 2002; Rescorla & Alley, 2001). Rescorla et al. (2005) showed, too, that rankings on the LDS and CDI were highly correlated, suggesting they are equally valid screening tools. Klee et al. (2000) also reported that the number of false positive results decreased when questions about ear infections and whether parents were concerned about the child’s language development were added to the LDS criterion of less than a 50-word expressive vocabulary or no word combinations for 24-month-olds. Although there are no current mandates for universal screening for toddlers for language delay, these instruments can be given to parents who have concerns about their children’s language development, as a first step toward deciding whether further evaluation is needed. Clinicians can also distribute these instruments to local pediatricians. In fact, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening for toddlers to detect autism spectrum disorder (ASD), although the brief checklists used for this purpose are likely to detect children with language disorders, as well. The SLP can work with pediatricians’ offices to review these screeners to decide whether any referrals to birth-to-3 services should be made. For toddlers who have delays in cognition, motor, social, and other areas besides language, evaluation is clearly warranted. But not all would agree that an otherwise typical child of 18 to 36 months who fails to begin talking or who talks very little is evidencing significant delay. Many professionals both in and outside the field of language pathology would hesitate to label a child with no other difficulties outside of speech development as “language disordered” before the third or even the fourth birthday (Rescorla & Lee, 2001), for just the reasons mentioned earlier—that many children who are slow to start talking eventually catch up. Providing intervention at the 18- to 36-month level for such children would not be cost-effective. Early intervention, although known to be effective when necessary, is expensive. It is wise to conserve such resources for children who really need them. So who needs them? Ellis and Thal (2008), Whitehurst and Fischel (1994), and Paul (1996, 1997a) have argued that, for children in the 18- to 36-month age range, the decision to intervene should be based on an accumulation of risk factors. They suggested that children with cognitive deficits, hearing impairments or chronic middle ear disease, social or preverbal communicative problems, dysfunctional families, risks associated with their birth histories, or family history of language and reading problems (Bishop, Price, Dale, & Plomin, 2003; Lyytinen, Poikkeus, Laakso, Eklund, & Lyytinen, 2001; Zubrick et al., 2007) should receive highest priority for intervention. Brady, Marquis, Fleming, and McLean (2004); Campbell et al., (2003); McCathren, Yoder, and Warren (1999); Olswang, Rodriguez, and Timler (1998); and Paul and Roth (2011) suggested that additional factors, listed in Box 7-1, also be considered. In light of these suggestions, a detailed case history and comprehensive direct assessment of all these areas are important for any toddler referred for failure to begin talking. When a toddler with slow language development shows significant risk factors, intervention is clearly warranted. The goal of that intervention is secondary prevention—minimizing the effects of the delay on the acquisition of language. There are a variety of standardized instruments that can be used to evaluate toddlers for eligibility for birth to 3 services. Generally, regulations require that children show impairments in at least two areas in order to be eligible for services; whether expressive and receptive language constitute two separate areas varies from state to state. Clinicians will need to be familiar with the guidelines for their particular locality. However, informed clinician opinion is always part of the evaluation process, so test scores alone will not be adequate to establish eligibility. Because more than one area of deficit is typically required for eligibility, instruments that sample several areas of development are often used for this purpose. Some procedures that can be part of this evaluation are listed in Box 7-2. For toddlers without other known risk factors who are simply slow to start talking, deciding whether to intervene is more difficult. Intervention for this group may accomplish facilitation, hastening development that would eventually happen on its own, rather than induction. Children who have learning disabilities often have histories of delayed language development (Butler & Silliman, 2002; Catts, 1997; Catts & Kamhi, 1986; Maxwell & Wallach, 1984; Steele, 2004; Tallal, 2003; Weiner, 1985). Even late talkers who perform within the normal range in language and literacy measures by age 5 or 6 (Paul & Fountain, 1999) begin to show deficits in literacy skills later in development (Rescorla, 2002), and there is a risk that these will persist into adolescence (Rescorla, 2009; Snowling, Adams, Bishop, & Stothard, 2001; Snowling & Bishop, 2000). Early language intervention may serve a secondary preventive function, then, helping to minimize later effects on learning even when the more basic oral language problems resolve. In addition, Robertson and Weismer (1999), for example, showed that intervention for late talkers not only increased their language skills but resulted in improvements in social skills and reductions in parental stress, so there may be other important secondary effects of supplying early intervention to these children. Paul (2000b) has argued that perhaps the best approach for late talkers without additional risk factors is to provide parent training in language facilitation techniques, rather than direct intervention. Girolametto, Pearce, and Weitzman (1996) and Peterson, Carta, and Greenwood (2005) showed that parents of late talkers could be trained to produce positive effects on the amount of child speech, the size of child vocabulary, and the number of multiword combinations. Hadden and Fowler (2000) discussed the importance of developing active coordination among agencies serving young children with disabilities in order to smooth their transition from early intervention to preschool programs. SLPs can play an important role in developing these interagency relationships. Prendeville and Ross-Allen (2002) outlined a variety of ways SLPs can be effective members of transition teams. These include the following: • Providing families with information and support to participate in transition planning • Setting aside time to work with team members from both early intervention and preschool service providers to prepare a timely transition plan • Sharing information about adaptations, accommodations, resources, and developmentally appropriate activities with preschool staff • Actively helping preschool staff prepare the necessary services and supports to promote successful preschool placement Like children at the prelinguistic stage of development, children with emerging language still function primarily in the context of the family. Practice for this developmental level, too, must be family-centered in order to succeed. Many of the same principles we discussed for infants apply to our work with toddlers. ASHA (2008) Guidelines for early intervention practice emphasize the need for family-centered practice in this area. Dempsey and Keen (2008); Dinnebeil and Hale (2003); Dunst, Boyd, Trivette, and Hamby (2002); and Polmanteer and Turbiville (2000) discuss some of the considerations that are primary in working with families in early intervention. These include the following: • Spending time with the family to learn about their vision for the child and discussing what parents would like to see their child do as a result of intervention • Finding out what families expect from the program at the outset and discussing expectations in order to come to a consensus about what is reasonable to expect • Including the family’s assessment of the child in the assessment report; writing the report in the words used by the family • Including multiple ways for families to be involved in the child’s program; providing choices and options • Working together with families to choose natural environments as a source of learning opportunities • Reviewing progress with families to make sure new skills are used consistently across natural environments • Identifying important people with whom the child needs to practice communication skills • Working with families to find ways to use children’s interests to involve them in everyday learning opportunities • Providing families with opportunities to be involved in both direct work with their child and acquiring new knowledge and skills for interacting with their child • Enabling parents to decide on the correct balance for their family What do we mean by “normal language development” in toddlers? Considerable research in recent years has allowed us to flesh out the picture of what constitutes normal language skills in very young children, so that we can determine when development is falling behind. Paul and Shiffer (1991) and Wetherby, Cain, Yonclas, and Walker (1988) reported that children at about 18 months of age produced an average of two communicative acts per minute in interactive samples. The functions of these acts are usually to request objects or actions, to establish joint attention, or to engage in social interaction (Hulit & Howard, 2002; Wetherby et al., 2004). During the second year of life, many of these intentions are expressed not with words, but with gestures (Capone & McGregor, 2004) and vocalizations (Oller, 2000). By 24 months, children produce an average of five to seven communicative acts per minute (Chapman, 2000). The majority of these communicative acts consist of words or word combinations, although some nonverbal acts are still used. Between 18 and 24 months of age, then, children significantly increase their frequency of communication, both verbally and nonverbally, and move toward more frequent verbal expressions of intent. Luinge et al. (2006) and Nelson (1973) showed that most middle-class toddlers were combining words into simple two-word sentences by 18 to 24 months; Roulstone, Loader, Northstone, and Beveridge (2002) reported that 78% of typically developing 25-month-olds were using multiword utterances. Luinge et al. (2006) reported that 98% of 24- to 36-month-olds produced two-word sentences, 90% produced three-word sentences, and 84% produced four-word sentences at this age. Grove and Dockrell (2000) reviewed literature that demonstrates that there are predictable patterns in the ways words are first combined, with stable word orders that follow patterns in the adult language, and that the meanings expressed by children in their first “telegraphic” sentences conform to a small set of semantic relations. Stoel-Gammon (1987, 2002) indicated that normally developing 24-month-olds produced at least 10 different consonants and were 70% correct in their consonant productions. Luinge et al. (2006) reported that over 75% of 24- to 36-month-olds are more than 50% intelligible. Speech samples of these toddlers included a variety of syllable shapes, including consonant-vowel (CV) and CVC, in virtually every child, and two-syllable words in the majority; the most frequent two-syllable form was the CVCV reduplicated syllable. McLeod, van Doorn, and Reed (2001) also showed that 2-year-olds are beginning to produce consonant clusters, although they may not always be correct relative to adult targets. Detailing changes in expressive vocabulary size in the second and third years of life has been the focus of much recent research (e.g., Dale, 2005; Rescorla & Achenbach, 2002). Fenson et al. (2007) reported that average expressive vocabulary size at 18 months is about 110 words. Dale, Bates, Reznick, and Morisset (1989) have shown that, by 20 months, average productive lexicon size reaches 168 words. By 24 months, Fenson et al. found mean vocabulary size to be 312 words, and at 30 months, 546 words. Stoel-Gammon (1991) pointed out that there is a great deal of variability in lexicon size in young children, but that this variability decreases dramatically during the third year of life. At 18 months, the variability in vocabulary size is larger than the mean, so that more than 16% of children still have very few words at this age. However, by 24 months the average variation in vocabulary size is only half as large as the mean and 84% of children at this age have vocabularies larger than 150 words. At 30 months the standard deviation in vocabulary size is only 18% of the average lexicon size. This means that 84% of children at this age have vocabularies larger than 450 words. The degree to which a small expressive vocabulary represents a significant deficit increases drastically between 18 and 30 months of age. Traditional wisdom has been that comprehension precedes production. Receptive vocabulary size is always larger than the size of the productive lexicon; this is true even for adults. For example, if you read the sentence, “Her proclivity for using long sentences in lectures drove her students to distraction,” you would no doubt comprehend the word proclivity. But if you were asked to come up with a synonym for tendency you might not be so likely to produce proclivity. The child’s comprehension of a first word is usually about 3 months ahead of the production of a first word, and comprehension of 50 different words usually occurs about 5 months before the productive lexicon reaches this size (Benedict, 1979). In terms of sentences, though, comprehension is probably not so far ahead of production. Chapman (1978) argued that children in the 18- to 24-month age range probably understand only two to three words out of each sentence they hear (that is, about the same number of words per sentence that they are producing in their own speech). Luinge et al. (2006) found that over 90% of 12- to 24-month-olds understand two-word sentences and names for some body parts, but it is not until 24 to 36 months of age that the majority of children understand three-word sentences. The appearance of more sophisticated comprehension skills that they often achieve is related to their ability to use nonlinguistic information to supplement their knowledge of language. These comprehension strategies allow the child to combine cues from gestures, facial expressions, and the way they know things usually happen with their understanding of words. The result is that children can appear to comprehend a long sentence such as, “Why don’t you go close that door for me?” by combining their knowledge of the meaning of close and door with their understanding that adults usually ask children to do things (Paul, 2000a; Shatz & Gelman, 1973; Thal & Flores, 2001). The information presented here can help to guide us in determining whether a toddler is significantly behind in communicative skills. In some ways, this research may lead us to intervene more quickly than we might have earlier. The demonstration that children as young as 24 months communicate frequently, have large vocabularies, and are accurate in their phonological productions the great majority of the time may emphasize and make more obvious the deficits seen in children with slow communicative growth. In addition, Thal and Clancy (2001) show that the interaction between biological development and environmental input plays an important role in language acquisition, so that providing high-quality input can have significant effects on early development. Still, we want to use caution and remember the large variations seen in normal development. In this chapter we’ll look at some procedures that can be used to assess the various areas of communicative development in children with emerging language: symbolic play and gestural behavior, intentional communication, comprehension, phonology, and expressive language. We’ll then look at some guidelines for integrating these assessment data into the processes of deciding when and how to intervene with children at this developmental level. An alternative form of assessment used for children younger than 3 is the transdisciplinary approach (ASHA, 2008; Kritzinger, Louw, & Rossetti, 2001; Linder, 1993; Rossetti, 2001), sometimes called “arena assessment.” Transdisciplinary or arena assessments involve the child’s interacting with just one adult, a “facilitator,” who performs some formal and informal assessments. The other members of the team, including the SLP, observe the facilitator’s interaction with the client. They may ask the facilitator to present certain tasks to the child, and they take notes on their observations of the child’s behavior in the situation, but they do not interact directly with the client. This approach is useful for looking at very young children who may have difficulty responding to a changing parade of unfamiliar adult faces. Many of the assessment techniques we discuss in this section can be incorporated into transdisciplinary evaluation by having the SLP go over them with the facilitator before the client is seen and then by having the facilitator include them with his or her interactions with the child. For example, the SLP might ask the facilitator to do a play assessment or a communicative intention assessment (both of which are described in this chapter). The SLP could teach the procedures to the facilitator, gather the necessary materials, and explain the purpose of the assessment. During the interaction with the client, the SLP would observe and score the client’s responses on a prepared worksheet and also would note any other relevant behaviors the client displays. Transdisciplinary assessment is generally used to decide whether a young child is eligible for early intervention services. Once eligibility for speech and language services has been established, the clinician can do more in-depth criterion-referenced assessments during the course of the intervention program if additional information is needed to establish baseline function and choose intervention goals. Before deciding that a toddler has a communication problem, we want to be sure that the child has achieved a general developmental level consistent with the use of symbolic communication. This is a controversial area. Traditional Piagetian thinking on the relation between language and cognitive development held that children could not be expected to use symbolic language until they had achieved certain cognitive milestones, such as the understanding of object permanence, tool use, or symbolic play. A great deal of research on the relations between cognitive and language development (e.g., Tomasello, 2002; Witt, 1998) has suggested, though, that such simple prerequisite relations are not typically found in normal development. Thal (1991) explained that most researchers in this area do not believe that there is a general relationship between language and cognition. Instead there are what researchers call local homologies. Local homologies are specific relationships that occur at certain points in development. For example, Bates, Bretherton, Snyder, Shore, and Volterra (1980) have shown that in the single-word period, there is a strong relationship between the use of words as labels and the ability to demonstrate functional play, or to use objects in play for their conventional purposes, such as putting a toy telephone up to the ear. A little later, when children begin to combine words, this relationship decreases in strength. However, a relationship emerges between the ability to combine words and the ability to produce sequences of gestures in play, such as going through the series of motions to feed and bathe a doll. Later, this relationship, too, declines. Current thinking about these findings (e.g., Casby, 2003a; Crais, Watson, & Baranek, 2009; Watt, Wetherby, & Shumway, 2006) suggests that although particular cognitive skills are not necessarily prerequisites for language development in general, certain behaviors that can be observed in a child’s play and gestural behavior tend to go along with particular communicative developments. Brady et al. (2004) and McCathren et al. (1999) for example, showed that prelinguistic children with developmental disabilities who used symbolic play behaviors were likelier than those who did not to increase their rate of communication in an intervention program. If early symbolic behaviors are present, this would suggest that the language skill that normally appears along with them should be within the child’s zone of proximal development and that it should be teachable. If the play and gestural skills are absent, as well as the language, then we might attempt to elicit both the play and language skills in tandem, since their development seems to be parallel and they may reinforce or complement each other. Play assessment provides a specifically nonlinguistic comparison against which to gauge a child’s language performance. Play can be used as a context for examining cognitive skills often assessed in more traditional intellectual assessments (Dykeman, 2008; Linder, 1993). It can also be observed to gain insight into particular aspects of the child’s conceptual and imaginative abilities. The point of play assessment, and more generally of cognitive assessment at the 18- to 36-month level, is not to decide whether the child has the “prerequisite” cognitive skills for learning language. Language learning is more complicated than that. The main thing we have learned about the connection between language and cognition is that we cannot specify what their relationship is, except perhaps for very small segments of time, and even then there is no clear chicken or egg. The point of these assessments is to sketch a fuller picture of the equipment the child is bringing to the task of learning to talk. Knowing what play abilities the child has helps to decide, not so much the language skills the child is ready to learn, but the activities, materials, and contexts that will be most appropriate to encourage that learning and the conceptual referents on which it might focus. Play also is the most natural context for language learning. Knowing the level of play behavior that the child is able to use can help the clinician structure play sessions that will maximize the child’s participation and opportunities for learning. A variety of methods are available for assessing level of play skills in children at the 18- to 36-month developmental level. Several of these were outlined in Chapter 2. Any of these assessments can serve to identify the child’s play skills to determine how they can be put in the service of language acquisition. An additional assessment tool specifically designed for the toddler developmental level is the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales-Developmental Profile (Wetherby & Prizant, 2003). This procedure analyzes samples of interactive play behavior and allows the clinician to score both symbolic and combinatory play, in order to provide a general level of symbolic development that is relatively independent of language. It has been shown to be reliable and valid for identifying children with developmental delays in the emerging language period (Wetherby, Allen, Cleary, Kublin, & Goldstein, 2002). Another method is Carpenter’s (1987) Play Scale. This scale was designed to assess symbolic behavior in nonverbal children who don’t “talk out” their play, so that symbolic skills must be inferred from their interactions with objects. As such, the scale is useful both for nonspeaking toddlers and for older children at the emerging-language stage. To use this scale, a parent is asked to play with the child by engaging in four play scenes with appropriate props: a tea party, a farm, and scenes involving transportation and nurturing. Parents are asked to follow the child’s lead in interacting with each set of toys for just 8 minutes. Parents are advised to respond to the child in a natural way, but to let the child play without continually talking or giving directions. Parents are asked not to touch the toys unless invited to by the child and not to give suggestions for play. They are given specific prompts to provide only when the child will not touch or play spontaneously with a set of toys. A detailed description of this assessment can be found in Carpenter (1987). A sample of behaviors examined by this assessment and the ages at which they are mastered by more than 90% of children with normal development appear in Table 7-1. TABLE 7-1 *Play behaviors for which three examples were produced by more than 90% of children at given age in a play session in which children interacted with parent during four play scenes for 8 min each. Play scenes: tea party (dolls, table, chairs, eating and cooking utensils); farm animals; nurture (dolls, crib, toy comb, brush, bottle, telephone, hat); transportation (garage, cars, trucks, boats). Adapted from Carpenter, R. (1987). Play scale. In L. Olswang, C. Stoel-Gammon, T. Coggins, & R. Carpenter (Eds.), Assessing prelinguistic and early linguistic behaviors in developmentally young children (pp. 44-77). Seattle: University of Washington Press. McCune (1995) also provided a detailed method of analyzing play behavior. Using her system, the child is given a standard set of toys including a toy telephone, dolls, a toy bed and covers, a toy tub, a tea set, combs and brushes, a toy iron and ironing board, toy cars, toy foods, and similar items. The child is then invited to play with the objects along with a familiar adult. Criteria for analyzing the behaviors observed are ordered hierarchically; they are summarized in Table 7-2. The highest level of play the child exhibits spontaneously can be taken as the child’s current level of symbolic behavior. Once this has been established, an emerging level of symbolic play also can be identified by having the clinician model the next level of symbolic play. If the child imitates this model, emergence into the next level of symbolic behavior can be inferred. The types of symbolic behavior that the child can attain in assessments such as these can be used as contexts in which language intervention takes place. In addition, higher levels of play behavior can be modeled by the clinician and parents in informal interactions with the child. These models can help the client evolve toward more advanced modes of symbolic thinking that will, in time, provide even richer contexts for language acquisition. TABLE 7-2 Guidelines for Play Assessment Adapted from McCune, L. (1995). A normative study of representational play at the transition to language. Developmental Psychology, 31 (2), 206; Nicolich, L. (1977). Beyond sensorimotor intelligence: Assessment of symbolic maturity through analysis of pretend play. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 23, 89-99. Use of gestures is an additional aspect of symbolic behavior. Several studies have shown that gestures are highly related to language in early development (Bates & Dick, 2002; Crais, Watson, & Baranek, 2009; Goldin-Meadow & Butcher, 2003). Goldin-Meadow and Butcher (2003) discuss the fact that young children often rely on gestures to express meanings when they are still very limited in their verbal abilities, and that word-gesture combinations often lead the way to multiword speech. Evans, Alibali, and McNeil (2001) showed that children with language disorders, too, use gestures to express meaning that is beyond their linguistic capacity. Moreover, Goodwyn, Acredolo, and Brown (2000) showed that children whose parents used word-gesture combinations in interactions when they were infants outperformed control groups on language measures when they were toddlers. Both Capone and McGregor (2004) and Crais et al. (2009) showed that, for children with a variety of communication disorders, early use of gestures tends to predict language development. Gesture use, then, may be an important prognostic indicator for children with delayed language. Capone and McGregor (2004) discussed the types of gestures that can be assessed and the general sequence of gestural development (Table 7-3). Crais et al. (2009) showed that typically developing children as young as 9 to 12 months already express a range of communicative intentions through gesture, including protesting, making requests, seeking attention, initiating social games and initiating joint attention. TABLE 7-3 Gestures and Gestural Development in the Prelinguistic and Emerging Language Stages Adapted from Capone, N., & McGregor, K. (2004). Gesture development: A review for clinical and research practices. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47, 173-187. Two assessment instruments provide information on gesture production. The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (Fenson et al., 2007) includes questions for parents on child gesture production. The Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales (Wetherby and Prizant, 2003) also has a scale for observing gestures during a play interaction. Assessment of gestural use also can take place in the context of play assessment (Crais et al., 2009). Notations can be made when gestures appear, using a form like the one in Figure 7-1. Crais et al. (2009) provide guidance on interpreting the assessment of gesture. These are summarized in Table 7-4. Table 7-4 Gestural Behaviors Important in the Identification of Developmental Disorders Adapted from Crais, E., Watson, L., & Baranek, G. (2009). Use of gesture development in profiling children”s prelinguistic communication skills. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 95-108. A variety of scales are commercially available for assessing a range of communicative skills in children younger than 3. These measures can be used to provide a broad picture of communicative functioning and to decide whether, in general, it is commensurate with the child’s current functioning in other areas. Many of the general developmental assessments outlined in Box 7-2 provide a scale or subtest of language ability or contain some items that tap language skills. The Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment (Linder, 1993), for example, provides opportunities for observing social-emotional, cognitive, communicative, and sensorimotor skills in a play context. It is particularly useful for clinicians working within transdisciplinary assessment settings. However, it is often useful to look at language and communication skills more specifically in a child in the emerging language stage who is suspected of a delay in language development. In this way we can avoid confounding the child’s nonverbal abilities with any deficits in communication that might exist. This is particularly useful for toddlers suspected of having specific communication deficits rather than more general developmental delays. Here’s one strategy for assessing a child with emerging language: 1. Obtain general developmental level from assessment by a psychologist or developmentalist, using one of the general scales outlined in Box 7-2, or by a transdisciplinary team using Transdisciplinary Play-Based Assessment (TPBA). 2. If developmental level is near to or greater than 18 months, use the developmental level to guide a more in-depth comparison of language and nonlinguistic skills. First administer a play assessment (or use data from the TPBA to evaluate play behavior) as a nonverbal index of cognitive development. This index can be used to decide whether the child with emerging language appears to be at or near the level of symbolic development that would ordinarily accompany symbolic communication. 3. Assess language and communication and compare them to nonverbal abilities. If nonverbal symbolic and communicative abilities are both very low, then intervention may focus on providing play contexts that can elicit early symbolic behaviors while providing simple language input around the emerging levels of play. If, on the other hand, symbolic play is more advanced but communication and language are found to be at lower levels, more focused language elicitation techniques in appropriate play contexts may be used. There are two approaches to accomplishing the communication portion of this assessment. One is to use a formal assessment instrument. Appendix 7-1 lists instruments available either commercially or in the research literature. Some, such as the Language Development Survey (Rescorla, 1989) and the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (Fenson et al., 2007), use a parent-report format. Others use direct assessment or a combination of direct observation and parent report. The Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales—Developmental Profile (Wetherby & Prizant, 2003) provides an example of one form of direct assessment, and also has parent-report components. The instrument can be used with children who function at the emerging language stage but are as old as 6 years in chronological age. It also has been demonstrated to be valid with children from mainstream (Eadie et al., 2010) as well as culturally different backgrounds (Roberts, Medley, Swartzfager, & Neebe, 1997). Some additional assessment procedures appropriate for this developmental level can be found in Preschool Functional Communication Inventory (Olswang, 1996), Interdisciplinary Clinical Assessment of Young Children With Developmental Disabilities (Guralnick, 2000), Alternative Approaches to Assessing Young Children (Losardo & Notari-Syverson, 2001), and the Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System for Infants and Children (Bricker, Capt, & Pretti-Frontczak, 2002). All these sources include dynamic, criterion-referenced procedures that use developmentally appropriate approaches for evaluating young children. A second method of assessing communication involves using informal methods to examine communicative functioning in several domains independently. This strategy, advocated by Crais et al. (2009) and Paul (1991b), has the advantage of integrating assessment and intervention activities and allowing more detailed intervention planning. This is possible because, instead of a general level of communication, the procedure allows several areas of communicative behavior to be examined separately and a level of development established in each. In this way, a profile of communication and related abilities can be derived, and specific intervention targets in nonverbal communication, expressive language, receptive language, and phonology can be readily identified. Paul (1991b) outlined informal procedures for profiling early communicative skills. Many areas assessed in this procedure are very similar to those examined in the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales (Wetherby & Prizant, 2003). This procedure is described in some detail here, not as an endorsement, but to give the student clinician a detailed idea of what is involved in informal assessment of the various areas of communication at this developmental level. There are several ways in which communication typically changes over the course of the second and third years of life. One way is that it becomes more verbal, with nonverbal means of communication gradually giving way to more conventional verbal forms. Another way is that attempts increase in frequency, with rates of communication more than doubling over the 18- to 24-month period. A third way is that the range of intentions the child is trying to express broadens. The result of all these changes is that by the third birthday, the normally developing toddler is more like an adult speaker than like his or her 1-year-old counterpart. Paul and Shiffer (1991), Pharr, Ratner, and Rescorla (2000), and Rescorla and Mirren (1998) showed that late-talking toddlers generally show lower rates of communication, vocalization, initiation, and joint attention, even nonverbally, than their typical peers. To assess communicative function in this age range, we need to observe the child playing with some interesting toys and a familiar adult. Casby (2003b) and Westby (1998b) emphasize the importance of providing low-structure interactions in which toys are accessible and the adult follows the child’s lead. This encourages the child to call the adult’s attention to himself and his actions and prevents an over-representation of request acts. The same toys used in the play assessment can be used here. In fact, if the play assessment is videorecorded, it can be viewed again as a sample of communicative behavior. Because the rate of communication is generally quite low at this developmental level, though, it also is possible to observe communicative behavior without recording but by simply watching a client interact with a parent. After some practice, most clinicians can learn to score communicative behavior in real time (Coggins & Carpenter, 1981), so long as this is the only behavior they are trying to observe. If play assessment also is to be done from a real-time observation, it will have to be done in a separate session, even if the same materials and participants are involved. There are a variety of schemes for summarizing the communicative functions typically seen in normally developing toddlers (see Chapman, 1981; Paul & Shiffer, 1991; and Wetherby et al., 1988, for review). Perhaps the most accessible system, though, is the one outlined by Bates (1976) and elaborated by Coggins and Carpenter (1981). Bates divided early communication into two basic functions: proto-imperatives and proto-declaratives. Proto-imperatives are used to get an adult to do or not do something. They include the following: Requests for objects: Solicitation of an item, usually out of reach, in which the child persists with the request until he or she gets a satisfactory response. Requests for action: Solicitation of the initiation of routine games or attempts to get a movable object to begin movement or reinitiate movement that has stopped. Rejections or protests: The expression of disapproval of a speaker’s utterance or action. Proto-declaratives are preverbal attempts to get an adult to focus on an object or event by such acts as showing off or showing or pointing out objects, pictures, and so on, for the purpose of establishing social interaction or joint attention. By far the most frequent proto-declarative function seen in normally developing toddlers (Paul & Shiffer, 1991) is the comment, which is used to point out objects or actions for the purpose of establishing joint attention. Comments are very important in the development of mature language because they establish the framework for the topic-comment structure of adult conversation. Social-interactive intentions, such as showing off or calling attention to self, can also be included in this category. Both proto-imperative and proto-declarative intentions appear in normally developing toddlers between 8 and 18 months of age. Beyond these earliest appearing intentions, several new communicative functions appear for the first time at about 18 to 24 months in normally developing children. These new intentions are evidence of more advanced levels of communicative behavior. They have what Chapman (1981, 2000) called discourse functions; that is, they refer to previous speech acts rather than objects or events in the world. They indicate that the child has now incorporated some of the basic rules of conversation into a communicative repertoire, such as the conversational obligation to respond to speech. These discourse functions include the following: Requests for information: Using language to learn about the world. At the earliest stages, the requesting information function can take the form of requests for the names of things (“Whazzat?”). Later, they may include a wh- word, a rising intonation contour, or both. Acknowledgments: Providing notice that the previous utterance was received. In young children this is often accomplished verbally by imitating part of the previous utterance or nonverbally by mimicking the interlocutor’s intonation pattern. Head nods also can communicate this intention. Answers: Responding to a request for information with a semantically appropriate remark. These more advanced intentions, then, are evidence of a higher level of communicative function than the use of the earlier set alone. All seven of the communicative functions we’ve discussed are listed on the Communication Intention Worksheet in Figure 7-2.

Assessment and intervention for emerging language

Issues in early assessment and intervention

Screening and eligibility for services

Transition planning

Family-centered practice

Communicative skills in normally speaking toddlers

Assessment of communicative skills in children with emerging language

Multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary assessment

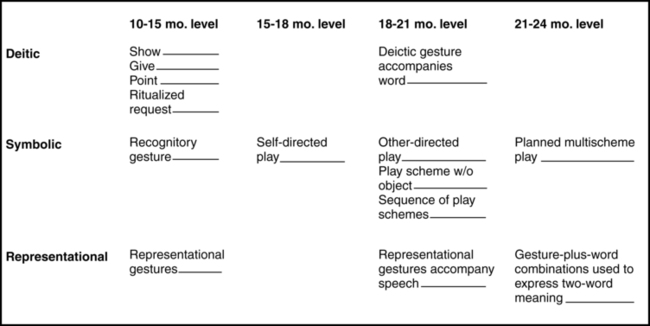

Play and gesture assessment

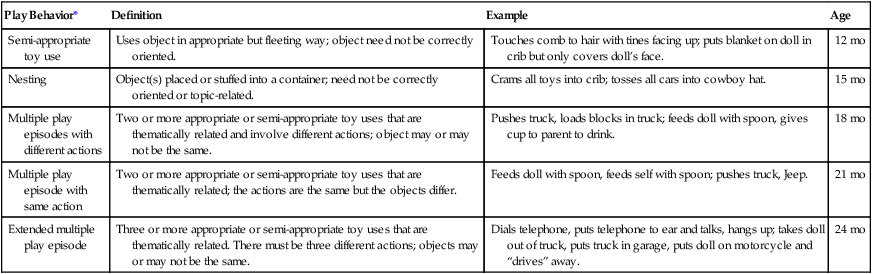

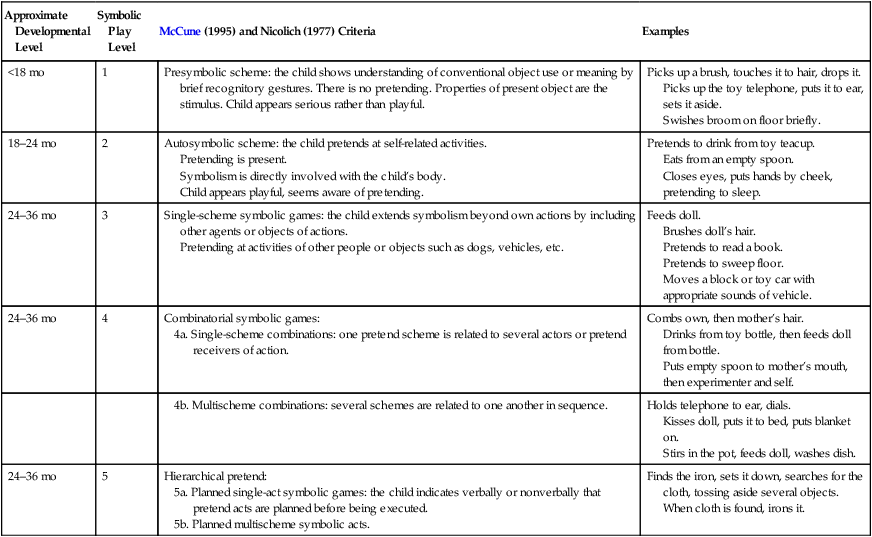

Assessing play

Play Behavior*

Definition

Example

Age

Semi-appropriate toy use

Uses object in appropriate but fleeting way; object need not be correctly oriented.

Touches comb to hair with tines facing up; puts blanket on doll in crib but only covers doll’s face.

12 mo

Nesting

Object(s) placed or stuffed into a container; need not be correctly oriented or topic-related.

Crams all toys into crib; tosses all cars into cowboy hat.

15 mo

Multiple play episodes with different actions

Two or more appropriate or semi-appropriate toy uses that are thematically related and involve different actions; object may or may not be the same.

Pushes truck, loads blocks in truck; feeds doll with spoon, gives cup to parent to drink.

18 mo

Multiple play episode with same action

Two or more appropriate or semi-appropriate toy uses that are thematically related; the actions are the same but the objects differ.

Feeds doll with spoon, feeds self with spoon; pushes truck, Jeep.

21 mo

Extended multiple play episode

Three or more appropriate or semi-appropriate toy uses that are thematically related. There must be three different actions; objects may or may not be the same.

Dials telephone, puts telephone to ear and talks, hangs up; takes doll out of truck, puts truck in garage, puts doll on motorcycle and “drives” away.

24 mo

Approximate Developmental Level

Symbolic Play Level

McCune (1995) and Nicolich (1977) Criteria

Examples

<18 mo

1

Presymbolic scheme: the child shows understanding of conventional object use or meaning by brief recognitory gestures. There is no pretending. Properties of present object are the stimulus. Child appears serious rather than playful.

Picks up a brush, touches it to hair, drops it.

Picks up the toy telephone, puts it to ear, sets it aside.

Swishes broom on floor briefly.

18–24 mo

2

Autosymbolic scheme: the child pretends at self-related activities.

Pretending is present.

Symbolism is directly involved with the child’s body.

Child appears playful, seems aware of pretending.

Pretends to drink from toy teacup.

Eats from an empty spoon.

Closes eyes, puts hands by cheek, pretending to sleep.

24–36 mo

3

Single-scheme symbolic games: the child extends symbolism beyond own actions by including other agents or objects of actions.

Pretending at activities of other people or objects such as dogs, vehicles, etc.

Feeds doll.

Brushes doll’s hair.

Pretends to read a book.

Pretends to sweep floor.

Moves a block or toy car with appropriate sounds of vehicle.

24–36 mo

4

Combinatorial symbolic games:

Combs own, then mother’s hair.

Drinks from toy bottle, then feeds doll from bottle.

Puts empty spoon to mother’s mouth, then experimenter and self.

Holds telephone to ear, dials.

Kisses doll, puts it to bed, puts blanket on.

Stirs in the pot, feeds doll, washes dish.

24–36 mo

5

Hierarchical pretend:

Finds the iron, sets it down, searches for the cloth, tossing aside several objects. When cloth is found, irons it.

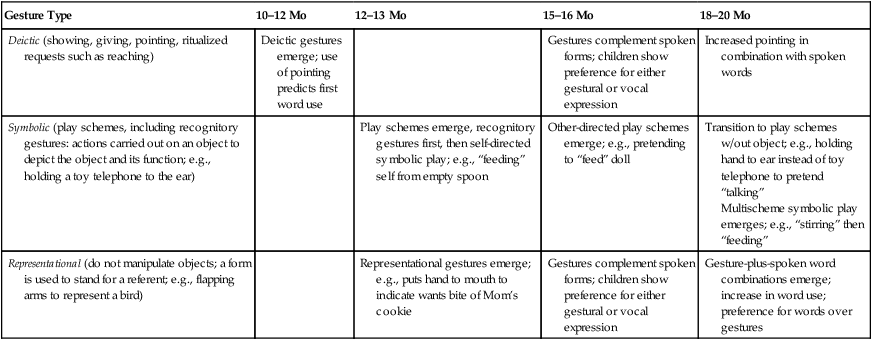

Assessing gesture

Gesture Type

10–12 Mo

12–13 Mo

15–16 Mo

18–20 Mo

Deictic (showing, giving, pointing, ritualized requests such as reaching)

Deictic gestures emerge; use of pointing predicts first word use

Gestures complement spoken forms; children show preference for either gestural or vocal expression

Increased pointing in combination with spoken words

Symbolic (play schemes, including recognitory gestures: actions carried out on an object to depict the object and its function; e.g., holding a toy telephone to the ear)

Play schemes emerge, recognitory gestures first, then self-directed symbolic play; e.g., “feeding” self from empty spoon

Other-directed play schemes emerge; e.g., pretending to “feed” doll

Transition to play schemes w/out object; e.g., holding hand to ear instead of toy telephone to pretend “talking”

Multischeme symbolic play emerges; e.g., “stirring” then “feeding”

Representational (do not manipulate objects; a form is used to stand for a referent; e.g., flapping arms to represent a bird)

Representational gestures emerge; e.g., puts hand to mouth to indicate wants bite of Mom’s cookie

Gestures complement spoken forms; children show preference for either gestural or vocal expression

Gesture-plus-spoken word combinations emerge; increase in word use; preference for words over gestures

Gestural Factor

Consequence

Frequency

Toddlers with a variety of disabilities use fewer gestures than typical peers.

Type

Onset of pointing predicts language development; children with ASD and Down syndrome are frequently late to acquire pointing.

Communicative function

Limited variety of gestures (particularly for the purpose of joint attention and social interaction functions) in toddlers 18–24 months is associated with later diagnosis of autism and other developmental disabilities.

Coordination of gesture with gaze and vocalization

By 15 months, typically developing toddlers combine gestures with gaze and/or vocalization. Lack of this coordination is associated with language delay and/or ASD.

Transition from contact to distal gestures

Failure to acquire gestures to indicate objects at a distance is associated with developmental disorders; it is frequently seen in ASD.

Transition to words

By 16 months, typical toddlers use words and gestures to name objects, by 20 months words predominate as names for objects. Children who persist in using gestures to label objects after 20 months may evidence language delay.

Communication assessment

Assessing communicative intention

Range of communicative functions

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Assessment and intervention for emerging language

Joey had been a difficult baby. He’d cry inconsolably for hours on end, and the only way his parents could calm him was to put him in his car seat and drive around. Even at 6 months, when most babies have outgrown their colicky stage, Joey continued to be extremely irritable and unable to find comfort in his parents’ cuddling and attention. He sat up at only 4 months, walked at 11 months, and at that time began to take an interest in objects that bounced or sprang. He spent long periods playing with rubber bands. He was quiet, too, and didn’t seem to babble as much as his parents’ friends’ babies. When he was 18 months old, he said a few phrases, usually echoes of what he’d heard before, such as “Go, dog, go,” or “I’m lovin’ it” He didn’t seem to be learning a lot of new words, though, and he didn’t seem to listen when people talked to him or even turn when they called his name. Still, he was very good at letting people know what he wanted. He would take adults’ hands and lead them to things. It didn’t seem to matter much who the adult was, though. Once he got what he wanted, he was content to play with it alone for long periods. Everyone told his parents there was nothing to worry about; Joey was just a “late bloomer.” When he had his second birthday, Joey’s mother took him to the pediatrician for a checkup. The doctor asked about Joey’s speech, and his mother reported that he said a few things. She commented that Joey’s brother Bobby had talked a blue streak when he was 2 and said she remembered taking him to an amusement park for his second birthday present. She recalled that he’d known the names of all the animals on the merry-go-round and had labeled each one as it went past. She knew that all children were different, but maybe Joey really was slow in his speech. She expressed her concern to the doctor. Her pediatrician recommended that Joey have his hearing tested. When the test came back within normal limits, the pediatrician reassured her that Joey would probably grow out of his slow start in speech.

Joey had been a difficult baby. He’d cry inconsolably for hours on end, and the only way his parents could calm him was to put him in his car seat and drive around. Even at 6 months, when most babies have outgrown their colicky stage, Joey continued to be extremely irritable and unable to find comfort in his parents’ cuddling and attention. He sat up at only 4 months, walked at 11 months, and at that time began to take an interest in objects that bounced or sprang. He spent long periods playing with rubber bands. He was quiet, too, and didn’t seem to babble as much as his parents’ friends’ babies. When he was 18 months old, he said a few phrases, usually echoes of what he’d heard before, such as “Go, dog, go,” or “I’m lovin’ it” He didn’t seem to be learning a lot of new words, though, and he didn’t seem to listen when people talked to him or even turn when they called his name. Still, he was very good at letting people know what he wanted. He would take adults’ hands and lead them to things. It didn’t seem to matter much who the adult was, though. Once he got what he wanted, he was content to play with it alone for long periods. Everyone told his parents there was nothing to worry about; Joey was just a “late bloomer.” When he had his second birthday, Joey’s mother took him to the pediatrician for a checkup. The doctor asked about Joey’s speech, and his mother reported that he said a few things. She commented that Joey’s brother Bobby had talked a blue streak when he was 2 and said she remembered taking him to an amusement park for his second birthday present. She recalled that he’d known the names of all the animals on the merry-go-round and had labeled each one as it went past. She knew that all children were different, but maybe Joey really was slow in his speech. She expressed her concern to the doctor. Her pediatrician recommended that Joey have his hearing tested. When the test came back within normal limits, the pediatrician reassured her that Joey would probably grow out of his slow start in speech.