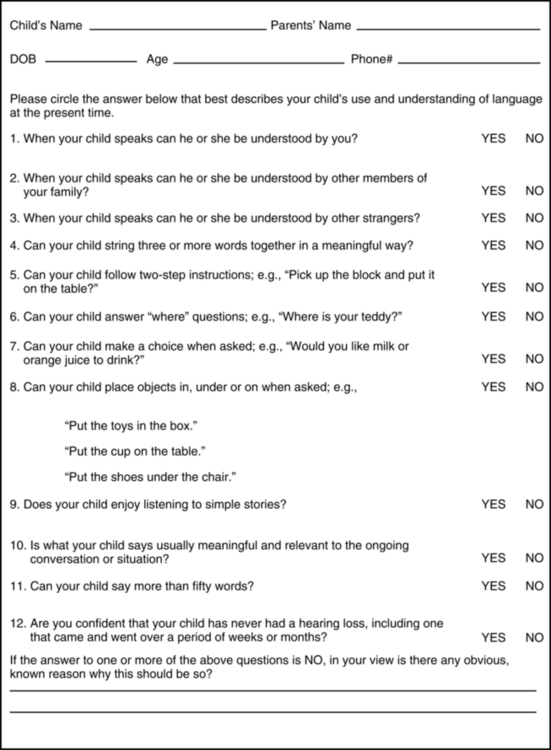

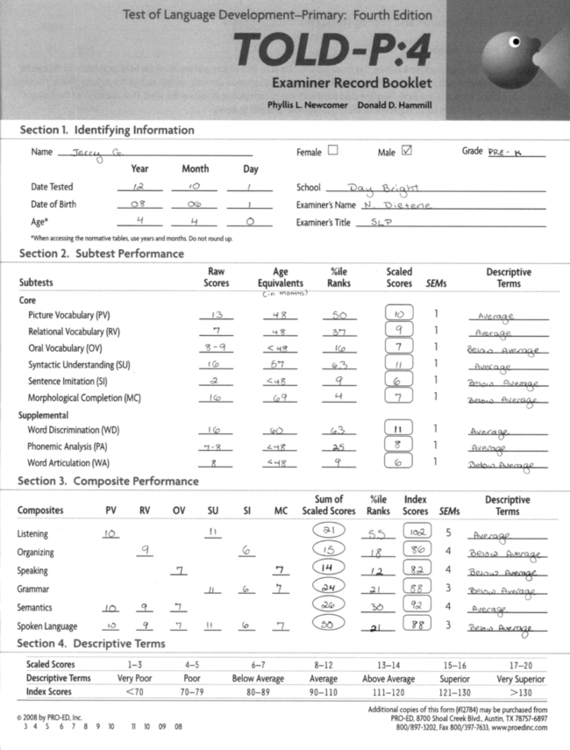

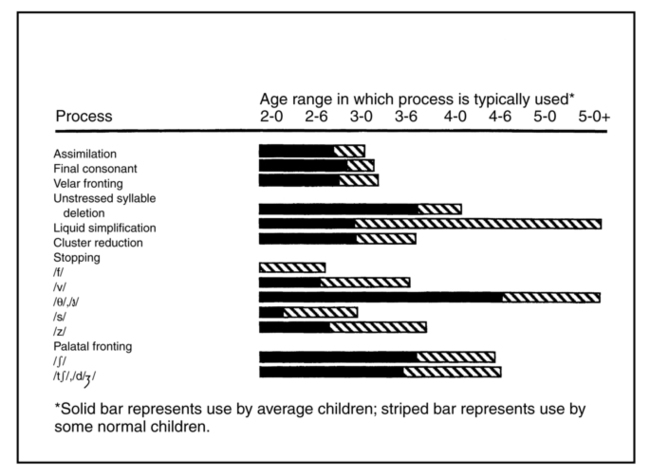

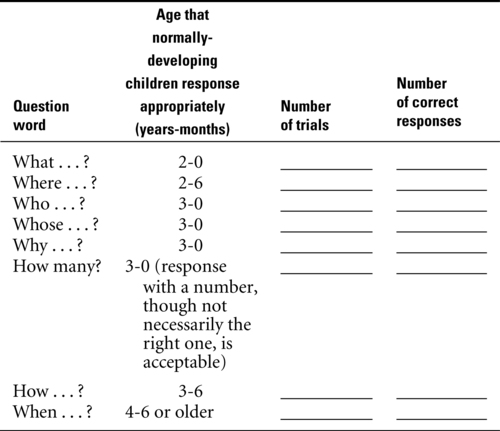

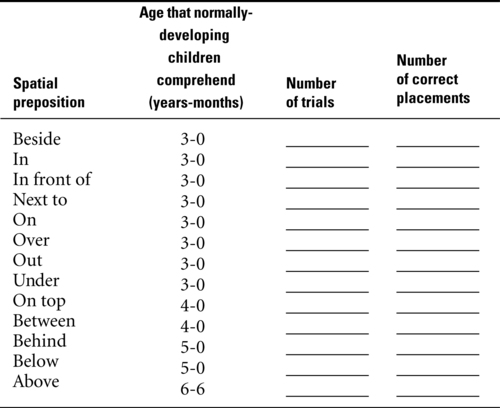

Chapter 8 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Describe family-centered assessment procedures appropriate for preschool clients. 2. List areas outside of communication abilities that are necessary to assess in young children. 3. Discuss issues and methods for screening for communication disorders in preschool children. 4. Discuss the uses and abuses of standardized tests for communication assessment during the preschool period. 5. Describe a range of criterion-referenced and observational methods for assessing speech and language development. 6. Analyze samples of communication including conversation and narration. 7. Discuss the application of assessment methods for children at early stages of language development to older students with severe communication disorders. • They have expressive vocabularies larger than 50 words. • They have begun combining words into sentences. • They have not yet acquired all the basic sentence structures of the language. For children who are of preschool age but have expressive vocabularies smaller than 50 words or are not yet combining words, more appropriate assessment and remedial strategies can be found in Chapter 7, which deals with the emerging language period when first words are beginning to appear and a few two-word combinations may be used. Children who are functioning at the emerging-language level, even if they are of preschool age or older, benefit most from procedures aimed at this early phase of language development. The period we’ll call the “developing language” stage is the one that occurs when normally speaking children are between 2 or 3 and 5 years of age. Another way to describe this period is to say that it refers to language levels in Brown’s stages II through V. That is, children with developing language have mean lengths of utterance (MLU) of more than two but generally not much more than five morphemes. These children are in the most explosive stage of language development, the period in which they move from telegraphic utterances to the mastery of basic sentence structures. For children with typical development, this process begins around 2 years of age and proceeds rapidly during the preschool period. For children with disorders of language learning, though, the process is more protracted. They may be a good deal older than 2 when they start it, and they may be well into school age before they complete it. When we discuss language assessment and intervention at the developing language level here and in Chapter 9, we are referring to those children whose language functions in the period between Brown’s stages II and V. The children themselves, though, may be chronologically older than preschool age. The principles of this and the following chapter can be applied to children of any age who have started combining words but have yet to develop the full set of forms for expressing their intentions. Family-centered practice means more than merely complying with these legal requirements, though. In addition, it means that we rely on parents as an important source of information about the child. We discussed interviewing parents on developmental and history information in Chapter 2. Standardized interview formats, such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales II (Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005), can be used to help establish general developmental level. Questionnaires about general and medical history can be used to gather information from parents as well. But family-centered practice also means that, from the first encounter with the family, we convey to them a sense of “being in this together,” a desire and intention to address the family’s concerns about the child and to respect the family’s point of view. As discussed in Chapters 6 and 7, family involvement does not necessarily mean that the family must be evaluated along with the child. This is often both off-putting and threatening to families. It does mean that we need to seek the family’s perspective on the child’s strengths and weaknesses, identify the family’s concerns for the child, and find out what priorities the family has for the skills the child needs to learn to function most effectively. Let’s take Jerry as an example. Suppose the family takes Jerry to the preschool assessment center of the local educational agency. The parents talk with the assessment team leader and the SLP there about Mrs. Hamilton’s recommendation. They express some dismay that Jerry seems to be having so much trouble, since they haven’t experienced difficulties with him at home. They say Mrs. Hamilton thinks he is bright, but now they wonder whether he might be retarded. Their main concern is helping Jerry get along better in school and avoid any problems when he reaches kindergarten. They don’t want him labeled a “troublemaker.” How would we use a family-centered approach to assessment to deal with these concerns and use them to structure the assessment plan? First, we should try to assure parents that our evaluation reflects the “real” child. Assessment should be completed over a period of time in a variety of contexts, using naturalistic activities (Rini & Hindenlang, 2007). We want to ensure that the family is confident the team truly has a sense of who their child is. Second, we want to gather extensive information about the child from family members, so that they are assured that their perspective on the child is being included in the appraisal. Whether we used structured measures, like the Vineland or more informal interviews, we want to acknowledge that parents have the broadest and deepest knowledge about their child, and that we hope to draw on that knowledge as we conduct the evaluation. Third, all of the parents’ anxieties should be addressed. If the parents are worried that Jerry might have intellectual disability (ID), even if the assessment team does not believe this is very likely, his cognitive and adaptive skills ought to be assessed. Referral can be made for a psychological evaluation to assess cognitive level. Alternatively, the speech-language clinician might ask the family whether they would be comfortable with her doing an informal cognitive assessment based on play behavior. She might assure the parents that if the child performs within the normal range on this measure, further assessment might not be necessary, but if she has any concerns at all about cognitive functioning, a referral for testing in greater depth can be made. The speech-language clinician also can offer to use the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales II (Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005) to assess adaptive behavior, since a child must function below the normal range in both cognitive and adaptive areas to qualify for a diagnosis of ID. In any case, a family-centered approach requires that we take the parents’ concerns seriously and incorporate them into the assessment plan. Family-centered assessment, then, does not mean assessing families, trying to identify their weaknesses. Instead it means including families in the process of deciding why, what, and how to assess each child. Moreover, it means taking the family’s concerns seriously and treating parents as a valid and reliable source of information about the child. It also means respecting the parents’ decisions about their child, even when we disagree with them. While it is always appropriate to try to resolve disagreements through compromise and courteous persuasion, we will not always succeed. When we do not, family-centered clinicians defer to the family’s judgment and try to maintain a relationship with the family that will make them feel welcome to come back another time, when the child’s problems, or their feelings about them, change. Bruce, DiVenere, and Bergeron (1998); Dunst, Trivette, and Deal (1988); and Rini and Hindenlang (2007) provided additional discussion on family-centered practice. When we talked about assessment in Chapter 2, we discussed the importance of assessing every client referred for a speech or language disorder in the areas of hearing and speech-motor ability. This principle, of course, holds true for the child with developing language. Audiometric screening and, if necessary, full evaluation should be conducted, even if hearing problems have never been mentioned in the child’s medical history. Similarly, any child in the developing language phase who has difficulty talking should receive a thorough speech-motor assessment, following the guidelines given in Chapter 2. Some language clinicians, particularly those in private practice settings, function independently in their assessment activities, making referrals to other professionals for information on collateral areas outside their own field of expertise. The majority of clinicians who do assessment in school, hospital, or nonprofit agency settings, though, usually conduct their assessments as part of a multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary team, as we discussed in Chapter 2. It could be, though, that information on collateral areas of particular interest will not be within the expertise of anyone else on the team. When this is the case, a referral to an outside agency may be necessary. Alternatively, the clinician might decide to do some informal evaluation in these areas to get a sense of how they relate to the child’s language functioning. We’ve talked before about the dangers of requiring that certain cognitive skills be present before language skills are taught. If we see a child of preschool age who is unable to accomplish any object permanence tasks, for example, we do not want to conclude that the child cannot learn language. We know such simple prerequisite relationships do not capture the complexity of the interactions of cognitive and linguistic development (Johnston, 1994; Mainela-Arnold, Evans, & Alibali, 2006; Nelson, 2000; Whitmire, 2000a). Still, we do need to know something about the child’s general level of development, to help both in planning appropriate contexts and materials for intervention and in deciding on appropriate language goals. If, for example, a 7-year-old with a developmental delay is found to have a general developmental level of 15 to 18 months, we would want to focus on acquisition of single symbols, and stimulating language growth, using the goals and approaches advocated for children with emerging language (see Chapter 7) for some time. If, on the other hand, another developmentally delayed 7-year-old had a general developmental level of 30 to 36 months, we would focus more on approaches appropriate for children with developing language (that is, we would move more quickly from single words to two-word combinations and on to three- and four-word sentences and might consider more focused, clinician-delivered intervention). The point is that knowing something about general developmental level does not necessarily dictate what language skills are targeted, but it may influence the context, pace, and intensity of the intervention. Many standardized instruments are commercially available for screening purposes with preschool populations. A sampling of these is presented in Appendices 8-1 and 8-2. One example is the General Language Screen (Stott, Merricks, Bolton, & Goodyer, 2002), a parent-report screening measure for 3-year-olds that appears in Figure 8-1. Luinge, Post, Wit, and Goorhuis-Brouwer (2006) provide another example of a screening instrument designed to identify language delays in children 12 to 72 months old. Chiat and Roy (2007) suggest using a modified word repetition test, similar to but simpler than the non-word repetition measures used with school-aged children, to identify risk for language impairment in preschoolers. Choosing which instrument to use should not be based on random factors, such as what happens to be on the shelf or what was advertised in a recent catalog. As clinicians, we have a responsibility to review all testing instruments and to choose those that are the most efficient and fair. For screening, that means that we want a test that is short and psychometrically sound. Reasonable levels of sensitivity and specificity have been reported for some preschool language screeners, including the Early Language Milestone Scale—2 (Coplan, 1993), the Language Development Survey (Klee, Pearce, & Carson, 2000; Rescorla, 1989), the Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestone Scale (Clark, Jorgensen, & Blondeau, 1995), the Levett-Muir Language Screening Test (Levett & Muir, 1983), the Screening Kit of Language Development (Bliss & Allen, 1984), the Fluharty Preschool Speech and Language Screening Test (Allen & Bliss, 1987), the Language Use Inventory (O’Neill, 2007), the Sentence Repetition Screening Test (Sturner, Funk, & Green, 1996), and the Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test—Preschool: Second Edition (Dawson et al., 2004; Greenslade, Plante, & Vance, 2009). When we look for a screening measure, we should examine test manuals for information on sensitivity and specificity, as well as other psychometric properties (see Chapter 2). It is important to know the properties of the tests we use and to choose tests with properties that are the best match for the assessment question that we are trying to answer. In practice, this means we have an obligation to read the statistical sections of the manuals of all the tests we use and to base decisions about their use not only on their efficiency and attractiveness, but also on how well their measurement properties stack up. There ARE such things as bad tests: tests that are poorly constructed and do not give enough psychometric information for us to decide whether they test fairly and accurately. But there are very few tests that are so good that they are right for every situation. Clinicians need to match tests to their needs on the basis, at least to some extent, of the tests’ statistical properties. There’s one other consideration when doing screening: a child’s level of risk. When deciding whether to provide a more extensive evaluation, it is wise to factor risk into the decision. Harrison and McLeod (2010), after reviewing the literature on risk and studying a nationally representative sample of 4- to 5-year-old children, reported that boys were at greater risk for language impairment than girls, as were children with hearing impairments, and those with difficult temperaments. Family history of speech, language, reading, or learning problems also increased risk (Barry, Yasin, & Bishop, 2007). Knowing these risk factors can help to determine which children who may not fail screening, but simply score toward the low end, could benefit from additional evaluation in universal screening situations, or which children should get high priority for screening in others. In addition to the risk factors for language delay identified by Barry et al. (2007) and Harrison and McLeod (2010), we also need to think about risk for reading problems in preschoolers with oral language delays. Serry, Rose, and Liamputtong (2008) discuss the role the SLP can play in identifying preschoolers at risk for reading failure on the basis of their oral language difficulties. Both Flax et al. (2009) and Serry et al. (2008) suggest that, in addition to phonological processing delays, receptive language disabilities are key risk factors for the emergence of reading problems in preschoolers. These findings suggest that preschool children for whom teachers report delays in phonological awareness skills (such as identifying words that start/end with the same sound or rhymes) or in general comprehension are good candidates for screening and perhaps more in-depth assessment to reduce the risk of reading failure by shoring up weak phonological and language skills during the preschool years. Everything we just discussed about choosing screening instruments for children with developing language applies to choosing more in-depth standardized tests as well. Remember that the thing standardized tests do best is to show whether a child is significantly different from children in their norming samples, so every standardized test we use has a screening component. That means that when we choose a standardized instrument, we need to be sure that it provides us with some more information than we got from the initial screening test. If the standardized test only tells us again that the child is different from other children in general language skills, we have wasted our time and the child’s in giving it. Let’s look at what information is provided by standardized tests available for assessment of this stage of language development and see how they might enhance our evaluation of the client with developing language. A sample of standardized tests designed for use with children in the developing language phase is given in Appendices 8-3 and 8-4. Let’s take Jerry as our example again. Suppose Jerry, after failing a screening measure given by the SLP, is given the Test of Language Development—4 Primary (TOLD-4:P; Newcomer & Hammill, 2008) to explore his profile of language skills across a range of components of language. This test provides a standardized measure of several areas of expressive and receptive language and allows us to construct a profile such as the one in Figure 8-2, which displays Jerry’s scores on the TOLD-P:4. The profile tells us that Jerry is performing adequately in several areas of receptive language, but that his expressive skills, and particularly his articulation, are low for his age. This profile suggests that we need to focus on expressive areas of language development, including the area of phonology. Another strategy for obtaining similar information would be to choose several tests, each of which focuses on one area. For example, we might select the Test of Auditory Comprehension of Language—3 (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999a) to look at receptive vocabulary and syntax, the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation—Second Edition (GFTA-2; Goldman & Fristoe, 2000) to examine single-word pronunciation, the Expressive Vocabulary Test—2 (Williams, 2007) to investigate productive semantics, and the Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test—Third Edition (Dawson, Stout, & Eyer, 2003; Perona, Plant, & Vance, 2005) to explore expressive sentence structures. We could use the results from this test battery, too, to construct a profile that outlines strengths and weaknesses in language skills. For one thing, they are designed to sample a variety of behaviors within a domain so that they can get a valid comparison across children. That means there won’t be many examples of any particular structure. The Test of Auditory Comprehension of Language—3 (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999a), for example, has only one item that tests comprehension of plural forms. If Jerry fails that item, would you target plural forms as part of your remedial program? It’s hard to say. It’s possible that he really doesn’t understand the meaning of the plural marker, but there might be other reasons why a child might fail that item. Maybe he wasn’t paying very close attention at that moment. Maybe he didn’t know the words in the sentence. Before deciding to target plurals, we would want to see more of a pattern of performance. A standardized test is not designed to provide that kind of information. Here’s another reason that standardized tests don’t give us all the information we need for remedial planning. Take the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulatio—Second Edition (Goldman & Fristoe, 2000) or the Patterned Elicitation of Syntax Test (Young & Perachio, 1993). These measures will be very effective for showing us whether Jerry is different from other children in articulating single words and imitating grammatical sentences, respectively. However, research shows that although children’s scores on standardized and naturalistic language procedures are related, children do not make the same errors on both types of assessment, so we cannot identify forms for remediation from the standard test items (Morrison & Shriberg, 1992; Prutting, Gallagher, & Mulac, 1975; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1980). Moreover some children do better on tests than on naturalistic measures (Condouris, Mayer, & Tager-Flusberg, 2003), suggesting that the tests may not be fully tapping their difficulties in real life communication. Standardized tests, particularly those designed to measure expressive skills, tend to use elicited production formats. Standardized tests of expressive syntax usually require children to imitate sentences spoken by the examiner. Standardized tests of articulation require children to produce single words in response to pictures. Both these formats tend to elicit performance that is substantially different from the performance of the same children in spontaneous speech. Not only do children produce different frequencies of errors in these imitation and citation formats, they make different kinds of errors, too. So knowing the errors Jerry makes on one of these measures doesn’t tell us what errors he will make when he actually tries to talk to someone. It’s the errors that children make when they actually talk that we need to address in intervention, so we need to know what those are. Standardized tests do not necessarily give us this information. Criterion-referenced measures, such as language sampling, are much more valid and effective for gathering information on the errors children make in real communicative situations. A clinically useful approach to analysis of a child’s speech production is to start out just talking with the child for 5 to 10 minutes to get a sense of general intelligibility. Gordon-Brannan (1994) and Morris, Wilcox, and Schooling (1995) discussed issues in assessing intelligibility. Morris et al. advocate using the Preschool Speech Intelligibility Measure (PSIM), which consists of having children repeat a list of words. The child’s productions are recorded and listeners are asked to judge which word a child says on each trial from a group of similar sounding words (e.g., warm, store, swarm, for, horn, corn, door, torn, born, floor, storm, and form). This measure can be very useful for documenting changes in intelligibility over the course of an intervention program. As a more informal measure, it is useful for making an initial determination about whether intelligibility is impaired. The clinician can also rate intelligibility in a short conversation by estimating the proportion of intelligible words. Gordon-Brannan and Weiss (2006) advocate collecting a conversational sample and counting 200 consecutive words within the sample. The clinician then listens to this portion of the sample again, counts the number of unintelligible words, and divides by the number of words in the sample. This figure is then subtracted from 100 to get a percentage of unintelligible words. Beltyukova, Stone, and Ellis (2008) report that this method shows high reliability and discriminatory power. Gordon-Brannan & Weiss (2006) and Coplan and Gleason (1988) provide guidelines for judging when children in the developing language period show a lower level of intelligibility than would be expected for their age. These are summarized in Table 8-1. The Children’s Speech Intelligibility Measure (Wilcox & Morris, 1990) is another method available. Coplan and Gleason have shown that children whose intelligibility is below age expectations are at increased risk for the presence of a range of developmental disorders, not just speech delay. In fact, 46% of the children in their study who were identified on the basis of failing an intelligibility screen turned out to have developmental difficulties beyond speech and language, so identifying poor intelligibility in a preschooler should lead to a more intensive assessment of the child’s abilities in a range of areas of development. Table 8-1 Expected Relations between Age and Intelligibility in Typically Speaking Children Adapted from Gordon-Brannan, G., & Weiss, C. (2006). Clinical management of articulatory and phonic disorders. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins. If the short speech sample indicates that a client is hard to understand, the next step in our clinical procedure would be to do an articulation test. We also might do an articulation test if the child is intelligible but makes more articulation errors than we would expect on the basis of developmental level. Although, as Morrison and Shriberg (1992) showed, articulation tests do not always identify the pronunciation errors children will make in spontaneous conversation, they do reliably show whether a child is significantly different from other children. Articulation tests are relatively quick and easy to administer and score. As such, they are sensible approaches to the problem of deciding whether speech sound production is an area that needs to be addressed in an intervention program. An articulation test can be given to decide whether more information is needed about the child’s phonology. If the child scores within the normal range on the articulation test and intelligibility in conversation appears adequate, further assessment of speech sound production is not likely to be necessary. If a child scores below the normal range on an articulation test or conversational speech is judged hard to understand, we will want to examine the nature of the child’s speech sound difficulties. Shriberg (2010) has proposed a classification system for speech sound disorders without known cause in children. For most children in the developing language period, speech delay, which is identified in children 3 to 9 years old who show a pattern of sound deletions and/or substitutions, is the appropriate category label. Although most of these children will eventually develop typical speech, they are at increased risk for literacy delays (Hesketh, 2004; Leitao & Fletcher, 2004), as well as social difficulties, like those Jerry’s teacher pointed out. For these reasons, intervention is warranted, both to improve speech intelligibility and to help the child develop awareness of sounds so that risk for reading problems is reduced (Gillon, 2005a; Kirk & Gillon, 2007). Although speech delays are defined by the presence of sound omissions and substitutions, often these errors occur not in isolation, but in patterns. For example, a child may have trouble producing closed consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) syllables, regardless of the particular sound that comes at the end of the word. These patterns, which are often referred to as phonological processes (Prezas & Hodson, 2010), can sometimes be treated more efficiently than treating each individual sound error separately. For this reason, many clinicians will not only identify the individual omissions and substitutions a child makes, but will look for these kinds of patterns, as well. How would we accomplish this? One way is to look not only at the child’s responses to an articulation test, but to examine errors in spontaneous speech, as well. This approach allows us to analyze the child’s production at two levels (Williams, 2001): independent analysis, which describes what the child produces, regardless of whether it is correct by adult standards, and relational analysis, which compares the child’s production to adult targets and looks for error patterns. When we assessed speech sound production in the emerging language stage, we used primarily independent analyses. Let’s look at examples of the most common approaches to each of these types of analysis for children in the developing language period. Suppose, for example, that Jerry never produces a /z/ in the appropriate context. We might be tempted to try to teach him “how” to say /z/, perhaps using isolated sound drills and nonsense words. But suppose further that we find /z/ does appear in his phonetic inventory. Perhaps he uses it in one or two words where /d/ is required. Clearly, then, he knows “how” to say /z/. What we need to teach him is not how to say it but, as Shriberg (1987) has argued, when to say it. In this case, an approach to intervention focusing on whole words and meaningful contrasts, is appropriate. If /z/ never appeared at all in the phonetic inventory, then Jerry really does need to learn “how” to say the /z/ sound and an approach that focuses on motor production may be more appropriate. Shriberg (1993) has grouped consonants by their normal order of acquisition. He divided the 24 consonant phonemes of English into three groups: the early eight (those that are used first in development), the middle eight (the group that appears next), and the late eight (the group that appears latest in normal acquisition). Shriberg’s assignment of consonants to these groups is given in Box 8-1. This scheme can be useful in deciding where in the process of acquiring sounds a client is, based on the phonetic inventory. If the inventory contains only sounds from the earliest group, some articulatory and motor training work may be necessary to elicit later-developing sounds. If the inventory contains sounds from both the early and middle groups, more emphasis might be placed on getting the client to produce these sounds in their correct contexts. If sounds from all three groups are present but speech still contains many errors, then, we would want to concentrate on getting the child to use the sounds he or she already has in appropriate contexts. If middle and later sounds are present, but many early sounds are missing, we might conclude that this child is showing atypical speech sound development and might look for speech-motor or other organic bases of the disorder. Phonetic inventories are easy to collect from continuous speech samples, by simply listening to a recording of the sample and writing down or checking off the first appearance of each consonant the client uses. They can be very helpful in deciding which sounds are in the inventory and need not be approached with motor training or articulatory procedures. They also can help identify sounds that are truly absent, suggesting that the child needs to learn “how” to say them. Looking at the distribution of sounds and comparing them with Shriberg’s (1993) scheme also can be helpful in deciding whether speech sound acquisition is delayed or proceeding along a deviant course. Williams (2001) also suggested conducting a distributional analysis of the phonetic inventory to determine in what word positions (initial, medial, final) the child’s sounds appear. The relational analysis is used to determine not what sounds the child can say, but what differences exist between the child’s production and adult target forms. Articulation tests give us this information about individual sounds in individual words. But since the 1970s, speech researchers and clinicians have been interested in describing not just individual errors in child speech, but also the patterns or rules that govern these errors. One particular approach to analysis of error patterns has been productive in this research: the use of phonological simplification processes to describe sound changes. Simplification processes have been described in detail by many authors, including Ball and Kent (1999); Bauman-Waengler (2004); Bernthal and Bankson (2004); Creaghead, Newman, and Secord (1989); Gordon-Brannan and Weiss (2006); Grunwell (1987); Hodson and Paden (1991); Ingram (1976); and Shriberg and Kwiatkowski (1980). Detailed definitions and discussion can be found in these writings. For our purposes, let’s just say that simplification processes are a way of describing sound changes that appear to be rule-governed attempts, which apply across a class of sounds or syllable structures, to make pronunciation easier. One example of a phonological simplification process is unstressed syllable deletion. It applies across the class of words containing more than two syllables and results in productions in which the least stressed syllable is dropped (mato for tomato). Velar fronting is another example. It applies across all sounds produced in the velar position (in English /g/, /k/, and / There are many ways to conduct process analysis. Some methods resemble articulation testing. These elicit single words or single sentences from children and apply phonological analysis procedures, analyzing errors according to the type of simplification process used. The Clinical Assessment of Articulation and Phonology (Secord & Donohue, 2000), the Bankson-Bernthal Test of Phonology (Bankson & Bernthal, 1990), the Computerized Articulation and Phonology Evaluation System (Masterson & Bernhardt, 2001), and the Hodson Assessment of Phonological Patterns—Third Edition (Hodson, 2004) are some examples. Other approaches provide guidelines for reanalyzing data gathered from an articulation test by means of phonological analysis procedures. Khan and Lewis (2002) have developed one such procedure. Masterson, Bernhardt, and Hofheinz, (2005) showed that single word measures such as these provide sufficient and representative information for phonological evaluation. A brief conversational sample is a useful adjunct to single word testing, as a check on the representativeness of the single-word sample. Several procedures are available in the literature for organizing this analysis. Bauman-Waengler (2004); Grunwell (1987); Ingram (1981); Lund and Duchan (1993); Owens (2004); Shipley and McAfee (2004); Shriberg and Kwiatkowski (1980); and Williams (2001) provided guidelines for approaches to phonological analysis of continuous speech. Andrews and Fey (1986) suggested procedures for applying Hodson’s analysis scheme for single words to spontaneous speech. These samples can be relatively short; Shriberg and Kwiatkowski (1980) suggest 100 different words produced in spontaneous speech is enough. This would generally involve about 10 to 15 minutes of continuous speech on the part of the child. Since many children with phonological disorders are difficult to understand, Shriberg and Kwiatkowski suggested that instead of using an open-ended conversational format for eliciting the speech sample, as we did when we got our initial general measure of intelligibility, we use a more structured task. We can give the child a complex picture with lots of different items in it to describe, such as the pages found in a “big” Richard Scary book. These kinds of stimuli elicit a sample in which the referents are known and the gloss of the child’s speech is much easier to determine. Whether you use a conversational or picture description format to elicit your sample, you can reanalyze the same sample later for syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, and phonological information. So here’s how a clinician might proceed: 1. Give the child a complex picture book, and ask him or her to tell about some of the things in the picture. Or ask the child to engage in conversation around common play materials with the parent. 3. While the child is talking, quickly get down the gloss and phonemic transcription of the first 100 different words. (Have a piece of paper already labeled with two columns [gloss, phonemic transcription] and 100 numbered rows, or use the forms provided by Shriberg and Kwiatkowski [1980].) 4. Later, check the recording for any glosses or transcriptions you aren’t sure about. You also can collect your phonetic inventory during the same pass through the recording. Save the recording for later analyses of other language areas. 1. Final consonant deletion (leaving off the last sound in a CVC word, such as saying /da/ for dog). 2. Velar fronting (pronouncing /k/, /g/, and /ŋ/ as /t/, /d/, and /n/, respectively, such as saying /tʌb/ for cub). 3. Stopping (pronouncing fricatives as the corresponding stops, such as saying /to/ for sew). 4. Palatal fronting (producing palatal sounds in the alveolar position, such as saying /su/ for shoe). 5. Liquid simplification (substituting another sound for one of the liquids [/l/ and /r/], such as saying /wawi pap/ for lollipop). 6. Assimilation (making two sounds in a word more alike, such as saying /dadi/ for doggy). 7. Cluster reduction (dropping one or more sounds from a cluster or making substitutions within the cluster, such as saying /pe/ for play). 8. Unstressed syllable deletion (leaving off the least stressed syllable in a multisyllablic word, such as saying /næ næ / for banana). This analysis can tell us (1) which sounds are subject to simplification in which words; (2) what patterns of errors appear across sounds; (3) whether processes are fading out at the typical time in the typical order (Figure 8-3 provides information on the typical developmental sequence of phonological processes). (4) whether atypical processes appear (that is, whether a large number of errors cannot be assigned to any of the common patterns listed above); and (5) how consistent the use of each process is for each sound; that is, whether the child uses the process in every context or only in some. For example, does the child always substitute stops for fricatives, or only some of the time? With the information provided by this analysis, we can begin to formulate an appropriate intervention program for a child with speech delay. Williams, McLeod, and McCauley (2010) present detailed discussions of the various methods available for remediating speech sound disorders in children. Shriberg and Austin (1998) reported that 30% to 40% of children with language disorders also have speech problems. Furthermore, 15% to 20% of children with speech delays have concomitant problems in vocabulary, grammar, or both. This suggests that we must be careful not to let the child’s unintelligibility blind us to possible language components of the disorder. Every child who presents with speech sound delay should receive a thorough language assessment, to identify any areas of linguistic disorder that might not be obvious because the child’s speech is so hard to understand. The term phonological processing refers to a child’s ability to perceive, store, retrieve, and manipulate sounds for language (Serry, Rose, & Liamputton, 2009). (It’s important to keep this term separate from the term phonological processes, which refers to the rule-governed simplifications that are common in young children’s speech.) Phonological processing includes phonological awareness (skills such as the ability to detect rhymes, number of syllables, and first/last sounds in words), rapid automatic naming (such as saying the days of the week quickly), and phonological memory (seen in the ability to repeat unfamiliar nonsense words). These phonological processing abilities grow during the preschool period, and are well-known to be related to learning to read and spell (Anthony et al., 2007; Gillon, 2004; Serry et al., 2008). The implication for SLPs is that these abilities are another aspect of phonological development to consider in assessment, so that if we detect weaknesses in these areas, we can build some phonological processing activities into the child’s program, as a means of preventing later difficulties in learning to read (Gillon, 2005a). For younger preschoolers, under the age of 4, informal assessment of the ability to recognize and produce rhymes—by asking children to find two pictures out of three whose names rhyme or to complete rhymes such as “You like dogs and he likes _____(frogs)”—can alert the clinician to deficits in these earliest-emerging phonological processing abilities. For 4- to 5-year-olds, informal assessment of the ability to provide a word with the same first sound as a given word (“Can you think of a word that starts with the same sound as dog?”), to count syllables in words (Can you clap for each part in the word hippopotamus?) can help determine whether more in-depth assessment of phonological processing is indicated. Schuele, Skibbe, and Rao (2007) provide additional guidance on assessing phonological processing. Appendix 11-3 has more information on standard instruments for phonological process assessment. Finally, Shriberg et al. (2009) have developed a non-word repetition test appropriate for children as young as 3 years that can also be useful in identifying difficulties in phonological processing. Here’s the bottom line: children with speech and/or language delays as preschoolers are at risk for reading failure in school, and deficits in phonological processing increase this risk. For this reason, some assessment of phonological processing for preschoolers with speech and/or language delays can identify children at highest risk for difficulty in learning to read and can guide the clinician to include activities to promote phonological processing into the speech/language intervention program. There is some evidence that doing so will help to lessen later reading problems in these children (Gillon, 2005a; Justice, 2006; Skibbe et al., 2008). • Receptive vocabulary (by responding to words by picture pointing) • Expressive vocabulary (by naming pictures or defining words) • Receptive syntax and morphology (by pointing to one of several pictures, including contrasting foils that depict a sentence spoken by the examiner [Point to: “The boys are here.”]) • Expressive syntax and morphology (by imitating sentences or filling in blanks with words containing grammatical morphemes [“I have a dress; you have two . . .”]) Generally speaking, the size of receptive vocabulary is larger than that of expressive vocabulary in children, and children can commonly recognize a pictured item by name, even though they may not be able to come up with the label for the same item in a confrontation naming task. The conventional wisdom is that if a child can produce a word, he or she must understand what it means. This is not entirely true, though. Research on children’s word-learning strategies (Bloom, 2001; Dollaghan, 1985; Rice, Buhr, & Nemeth, 1990) suggests that preschoolers can pick up some notion of a word’s meaning from very brief exposure, but that the meaning will be quite limited until the child acquires additional experience with the word. Researchers call this strategy “fast mapping” (Carey, 1978). What it implies for us as clinicians is that children’s understanding of word meaning, even when they produce the word themselves, may be more limited than the adult’s understanding of the meaning of the same word. The result is that it is difficult, with children in the developing language phase, to make a clear differentiation between the knowledge required to understand a word and the knowledge required to use it. It is not entirely true to say that “comprehension precedes production,” because a word may very well be produced even when comprehension of the word is very limited, by adult standards. This implies that clinicians should handle receptive and expressive vocabulary knowledge in an integrated way. What does this mean in practice? It implies that we should not worry too much about assessing vocabulary separately in each modality and then treating each modality separately. If a child does poorly on a receptive vocabulary test, such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test IV (Dunn & Dunn, 2006), the logical next step in assessment is to use criterion-referenced methods to look at what words the child has difficulty understanding. But there would not seem to be a need to teach these words receptively first, before trying to get a child to say them. Since children normally say words with only limited knowledge of their meaning, production can be targeted from the beginning of the intervention program. In short, we would recommend a strategy, following Lahey (1988), of focusing on comprehension during assessment but on production during intervention. There are two exceptions. First, for children with very limited speech sound production, words should be selected for production that the child can pronounce or at least approximate. Schwartz and Leonard (1982) showed that children in the early stages of speech sound acquisition are selective about words that they try to produce, attempting only those that have at least a beginning sound that is already in their repertoire. For clients who are still in this very early stage of speech development, then, pronounceability should be a consideration in choosing words that we are trying to get the child to say. Intervention for vocabulary might focus on receptive skills while work is going on to increase the child’s speech sound repertoire. The second exception has to do with word retrieval. It may be that a child has a normal receptive vocabulary size on a standardized test but uses very few words in spontaneous speech or does very poorly on a naming test such as the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test—Revised (Brownell, 2000). We may suspect that the problem is the inability to recall words when needed for production rather than lack of knowledge of the words. Word-retrieval skills are often assessed in test batteries for learning-disabled children of school age, since word retrieval problems commonly coexist with reading deficits (Brackenbury & Pye, 2005; Wolf, Bally, & Morris, 1986). Retrieval is not typically included in the assessment of the child with developing language. However, if word retrieval appears to be a problem—because of a large decrement on an expressive vocabulary test when compared with the score on a receptive measure, or because the child seems to have trouble recalling words in spontaneous conversation—intervention should focus more sharply on helping the child to recall and produce the words he or she already knows, in addition to increasing vocabulary size. First, assess receptive vocabulary skills with a standardized instrument. • If the child scores below the normal range, do criterion-referenced assessment of word classes that are important in the child’s communicative environment. Target words identified in this assessment, using both receptive and expressive intervention activities, with the emphasis on production. Control for pronounceability with children in the early stages of speech acquisition. • If the child scores within the normal range on the receptive vocabulary test, but history or parent or teacher report indicates concern about word use, assess expressive vocabulary with a standardized naming test. Watch for signs of word-finding problems, such as circumlocutions, overly general labels (thingy), or inability to name items responded to correctly on the receptive test. If there is evidence of a retrieval problem, focus intervention on practicing the recall and production of already known words, providing strategies such as using phonetic and semantic cues for retrieval (see details in Chapter 12). Standardized measures of vocabulary typically tell us whether a child’s ability to recognize and produce the names of items pictured in the test is similar to that of other children. Sometimes we want to know what a child knows about a particular category of words. We may need this information because this set of words is important for the child’s success in preschool. Colors or spatial terms (in, on, under, beside, in front, behind, next to, and so on) needed for following directions might be examples. Perhaps the child needs a set of word meanings for getting along better in social situations. One example of this might be the child with autism who uses a lot of echolalia when answering questions. We might want to know whether this child comprehends the meaning of the question words, since research on echolalia (Prizant & Duchan, 1981) suggests that children with autism often use echoing as a response when they don’t know a more appropriate way to answer a question. Another example is verbs, which are known to be especially difficult for children with language disorders (Windfuhr, Faragher, & Conti-Ramsden, 2002), and are not frequently assessed on standardized tests. These kinds of word classes are reasonable targets for criterion-referenced assessment. Suppose we (or the client’s parents or teachers) identify a set of words that are important for a child who scored low on a vocabulary test to know. We can look at knowledge of these words by using a nonstandardized assessment protocol. A variety of games and informal procedures can be used to probe children’s knowledge of word meanings. For example, the understanding of question words can be assessed. James (1990) provided an order of acquisition of the understanding of question words. This order is given in Figure 8-4. One means of assessing the comprehension of these question words is to read the child a short, simple story and ask questions about it during the reading (for example, if reading Chicken Little, the clinician might read the first page, where Chicken Little tries to tell her friends the sky was falling, then ask, “What was falling?”). We would use this procedure to avoid testing memory rather than the question words of interest. The clinician can choose questions so that each question word is used at least three times. Using a checklist such as the one in Figure 8-5, the clinician can record the child’s responses to each trial of each of the question words used in the procedure. This alerts the clinician to the question words the child can answer appropriately and identifies the question words the child has trouble answering accurately. These may be targeted for the intervention program. Here’s another example: the “hiding game.” This procedure can be used to assess understanding of spatial prepositions. Normative data come from Boehm (1989). In the hiding game the clinician arranges two identical cups on the floor or table so that one is inverted and one is right side up. The clinician gives the client a raisin to hide from a somewhat backward puppet. The catch is that the child must hide the raisin in the place the clinician indicates. The clinician then tells the child to hide the raisin in locations such as in, on, under, beside, or next to a cup or between the cups. The child hides the raisin and the puppet then “looks” for it in the place the clinician said to put it. If the puppet finds the raisin where the clinician said it should go, the puppet wins the raisin. However, this puppet is a picky eater and does not like raisins, so he always offers the treat to the client. The game continues until each spatial preposition has been tested three times. Using a checklist such as the one in Figure 8-5, the clinician can assess the level of the child’s understanding of spatial terms and identify those that the child has trouble comprehending. These might be included as intervention targets. These are just two ideas. Clinicians can come up with a variety of “games” and activities such as these to get more information about a child’s comprehension of certain classes of words. Miller and Paul (1995) provided additional ideas. The point is this: when a child scores poorly on a standardized measure of receptive vocabulary, specific content categories can be probed with informal techniques when necessary. This kind of assessment allows us to evaluate a client’s understanding of meanings that are important in his or her communicative interactions. These meanings can, if found to be problematic, be included as targets of intervention. Unlike vocabulary, syntax and morphology need to be carefully assessed in each of the receptive and expressive modalities. The reason is this: children commonly produce sentence forms, such as agent-action-object constructions, even when they fail to perform correctly on comprehension tests of these same forms in settings where nonlinguistic cues have been removed (Chapman, 1978; Paul, 2000c). Knowing that a child produces a sentence type does not necessarily mean that the child fully comprehends the same sentence if it is spoken to him in a decontextualized format. We do need, then, to be careful about assessing comprehension and production of syntactic forms separately. Some writers (Lund & Duchan, 1993; Rees & Shulman, 1978) have raised the question of whether the difference between contextualized and decontextualized comprehension invalidates the use of standardized tests in this area. In real communicative situations, they argue, it is rarely necessary to get all the information needed for a response from the words and sentences. Many other cues are available, including knowledge of what usually happens in situations (often called “scripts” or “event knowledge”); facial, intonational, and gestural cues; and objects and events in the immediate environment that provide nonlinguistic support, to name a few. Most children can take advantage of all these additional cues to assist their understanding of the words and sentences they hear. But if these cues are removed, a child is likely to do more poorly. This is as true for normally developing preschoolers as it is for children with language problems (Naito & Kikuo, 2004; Paul, Fisher, & Cohen, 1988). Of course, most of our standardized and many of our nonstandardized methods of assessing receptive syntax and morphology use decontextualized settings. Children typically perform more poorly on these than they would if the same forms were used in a more normal communicative context. Is this a bad thing? As you might guess, the answer would be, “It depends.” It depends on how we interpret the results of the decontextualized assessments and whether we include some contextualized assessments for contrasting information. We can look at the decontextualized results as a window onto how much linguistic comprehension a child displays and as a way to identify linguistic forms than can cause problems when few other cues are available. This information is very useful for contrasting with performance on production tasks. It can help us determine whether the child can demonstrate linguistic comprehension for forms he or she is not using at all in speech; whether linguistic comprehension and production are about on par; or whether, as normally developing children do in some stages of development (Chapman & Miller, 1975), the child is producing some forms that he or she does not comprehend in decontextualized formats. Knowing how comprehension contrasts with production can help us to decide whether to focus strictly on production skills in the intervention program or whether activities that foster both comprehension and production—such as focused stimulation and verbal script approaches (see Chapters 3 and 9 for details)—might be more appropriate. In this way, looking at comprehension skills in decontextualized formats can be useful. Contrasting this performance not only with production but also with performance in more contextualized activities also can be very informative. Lord (1985) advocated this approach for looking at comprehension skills in children with autism. We believe it can be helpful for evaluating receptive skills in any child at a developing language level who has trouble with decontextualized comprehension. Here’s why: if a child can take advantage of the nonlinguistic cues in the environment, he or she is in a good position to benefit from intervention activities, such as child-centered approaches, that provide enriched language carefully matched to the nonlinguistic context. Child-centered activities would be an important component of intervention for such a child. But suppose a client does no better on a contextualized assessment than on a standardized test. Some research (Paul, 1990; Paul, Fisher, & Cohen, 1988) on children with autism and specific language disorders suggests that these children are not as efficient as normally developing preschoolers at integrating information from linguistic and nonlinguistic sources. For clients such as these, approaches that make use of naturalistic nonlinguistic context may provide too complex a mix of cues. These clients may need to have the input scaled down, with very clear, simple connections made between the forms being taught and their meanings. For these clients a less naturalistic, more structured form of input may be needed to increase receptive skills. 1. Use a standardized test of receptive syntax and morphology to determine whether deficits exist in this area. 2. If the client performs below the normal range, use criterion-referenced decontextualized procedures to probe forms that appear to be causing trouble. 3. If the client performs poorly on the criterion-referenced assessments, test the same forms in a contextualized format, providing familiar scripts and nonlinguistic contexts; facial, gestural, and intonational cues; language closely tied to objects in the immediate environment; and expected instructions. a. If the child does better in the contextualized format, compare performance on comprehension to production. Target forms and structures that the child comprehends well but does not produce as initial targets for a production approach. Target structures that the child does not comprehend well for child-centered, focused stimulation, or verbal script approaches to work on comprehension and production simultaneously. b. If the child does not do better in the contextualized format, provide more-structured, less-complex input using more hybrid and clinician-directed activities for both comprehension and production.

Assessment of developing language

Family-centered assessment

Assessing collateral areas

Screening for language disorders in the period of developing language

Using standardized tests in assessing developing language

Criterion-referenced assessment and behavioral observation for children with developing language

Assessing speech sound production

Age (MO)

Percent Intelligible Words

24

50

36

80

48

100

Independent analysis: phonetic inventory

Relational analysis: errors and error patterns

/) and results in the production of each one as the corresponding sound produced with the same manner, nasality, and voicing in the alveolar position (/d/, /t/, and /n/, respectively).

/) and results in the production of each one as the corresponding sound produced with the same manner, nasality, and voicing in the alveolar position (/d/, /t/, and /n/, respectively).

Assessing phonological processing: preventing reading failure

Criterion-referenced language assessment

Vocabulary

Guidelines for vocabulary assessment and intervention

Methods of criterion-referenced vocabulary assessment

Syntax and morphology

Receptive syntax and morphology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Jerry was the third child in the family, so when he was a little slower than his sisters to get started talking, no one thought much about it. But when he entered preschool at age 4, his teacher, Mrs. Hamilton, noticed that his speech seemed immature. He made mistakes that other 4-year-olds in the class didn’t make, such as leaving out the little words and endings in sentences. He’d say, “Me a big boy,” and “I want two cracker.” He seemed not to know the words for many things other children could name, and he often used vague or idiosyncratic labels to refer to common objects. He called a pineapple a “spiky,” for example. Some of his words were hard to understand, too. He made some errors, such as saying /fΛm/ for thumb, that were like those made by lots of 4-year-olds, but he also left out sounds and parts of words in ways that weren’t typical of children his age. He said “mato” for tomato and /bΛ/ for bug. All these errors combined made his speech difficult to understand at times. Mrs. Hamilton noticed that when Jerry had trouble making himself understood, he often became angry, sometimes hitting or pushing the child who did not get his message.

Jerry was the third child in the family, so when he was a little slower than his sisters to get started talking, no one thought much about it. But when he entered preschool at age 4, his teacher, Mrs. Hamilton, noticed that his speech seemed immature. He made mistakes that other 4-year-olds in the class didn’t make, such as leaving out the little words and endings in sentences. He’d say, “Me a big boy,” and “I want two cracker.” He seemed not to know the words for many things other children could name, and he often used vague or idiosyncratic labels to refer to common objects. He called a pineapple a “spiky,” for example. Some of his words were hard to understand, too. He made some errors, such as saying /fΛm/ for thumb, that were like those made by lots of 4-year-olds, but he also left out sounds and parts of words in ways that weren’t typical of children his age. He said “mato” for tomato and /bΛ/ for bug. All these errors combined made his speech difficult to understand at times. Mrs. Hamilton noticed that when Jerry had trouble making himself understood, he often became angry, sometimes hitting or pushing the child who did not get his message. / /k/ /g/ /f/ /v/ /t∫/ /dʒ/

/ /k/ /g/ /f/ /v/ /t∫/ /dʒ/