The waveform of the BAEP can be recorded in three different montages, through the use of just three electrodes. Peaks I through to V are visible on the ipsilateral recording and II–V on the contralateral recording. Recordings from the two earlobes also allow all five peaks to be seen. The figure usefully illustrates the comparative ease of distinguishing different peaks depending on the montage selected. In practice, all of these can be easily run at the same time. (Reprinted from Aminoff and Josephson [18]; with permission from Elsevier)

Tumors of CN VIII are known by a number of names, acoustic neuroma, vestibular schwannoma, and vestibular neuroma . For the most part, these tumors are derived from Schwann cells on the vestibular branch of CN VIII, so a vestibular schwannoma is possibly the best description [7]. Rarely the same tumor type can occur on the auditory portion of the nerve. These tumors are generally benign and slow growing. Many smaller tumors (or residual tumor after surgery) are treated with radiosurgery as an alternative to open surgery. Because both the vestibular portion and the auditory portion of CN VIII run so closely together for most of their length, monitoring of the BAEP is indicated in any tumor resection of CN VIII if the intent is to preserve hearing. Since posterior fossa craniotomy also places the brainstem at risk, the BAEP is also monitored as a way to detect brainstem ischemia. Bilateral BAEPs should always be recorded when possible. Although it is ideal for the IOM clinician to be able to participate in preoperative planning of these surgeries, in some instances this is not possible. If you can be part of the team preoperatively, it is helpful to know if there is any serviceable hearing left and to what degree. The patient’s facial nerve function can also be documented at this time since facial nerve monitoring will be performed during this type of case as well. In non-hearing preservation surgery, there is of course no need to stimulate the BAEP ipsilaterally, but the bilateral nature of the potential allows for an assessment of the brainstem function even after destruction of the auditory nerve. Microvascular decompressions (MVDs) for a number of conditions also can pose a risk to CN VIII, either directly or through ischemic changes. MVD of CN VIII is indicated in cases where the patient suffers from either disabling tinnitus (auditory portion) or positional vertigo (vestibular portion). BAEP monitoring should also be considered for MVD procedures to relieve trigeminal neuralgia (CN V), hemifacial spasm (CN VII), or glossopharyngeal neuralgia (CN IX) [1, 7–9].

Space-occupying lesions of the fourth ventricle can disrupt brainstem function. Because of its many relay stations within the brainstem (it is called the brainstem auditory evoked potential after all!), the BAEP is a useful monitor of brainstem health. In my practice, the most common reason for performing the BAEP is to assess the brainstem rather than hearing. However, it is important to remember that the brainstem performs a wonderful variety of neural functions and the BAEP only directly assesses a small function of the brainstem [10]. Tumors of the cerebellar pontine angle (CPA tumors) remain the most often indication for BAEP monitoring. Surgery to remove these tumors requires the neuromonitorist to bring their full armamentarium to the case , and that will undoubtedly involve the BAEP as well as EMG monitoring of the lower cranial nerves [11] and motor and sensory evoked potentials.

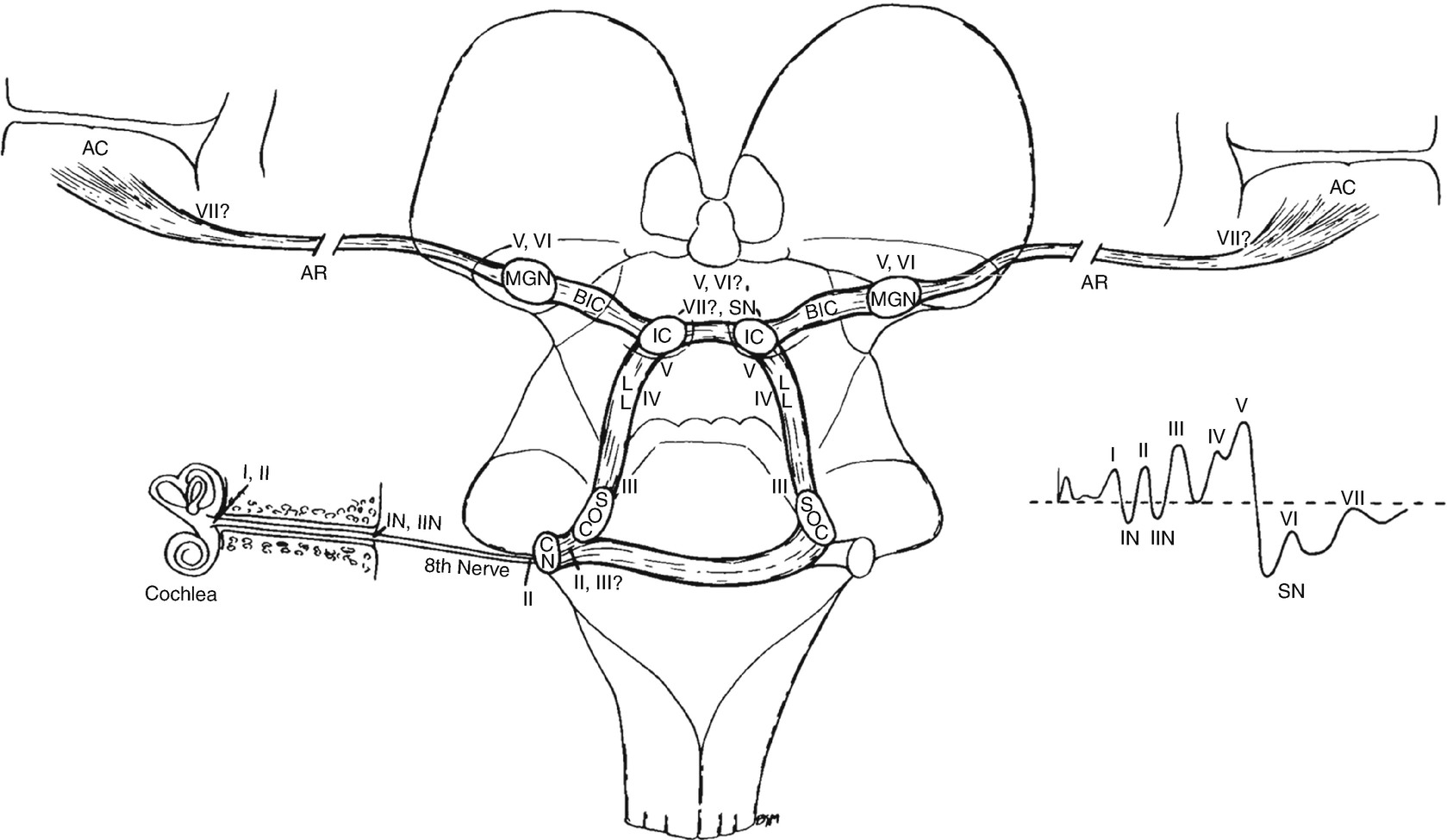

Peaks, Generators, and Blood Supply

The likely generators within the brainstem of auditory evoked potentials. The roman numerals refer to the individual peaks within the potential. CN cochlear nucleus, SOC superior olivary complex, LL lateral lemniscus, IC inferior colliculus, BIC brachium of the inferior colliculus, MGN medial geniculate nucleus, AR auditory radiations leading to AC, auditory cortex. (Reprinted from Aminoff and Josephson [18]; with permission from Elsevier)

Preoperative Considerations

Preoperatively, the neuromonitorist must determine the baseline hearing of the patient. Often audiologists assess this formally before the surgical procedure is planned. An appropriate stimulation level for intraoperative BAEPs can then be determined. Preoperative BAEPs may be helpful if there is time to obtain one. This is one of the easier evoked potentials to perform on an awake patient. Very few people find the process uncomfortable [3, 15]. Gathering these data before the surgery may give insight into any apparent abnormalities in the operative baseline and help distinguish between preexisting pathology and a technical issue. The size of the ear canal and whether it is occluded with earwax should also be determined prior to surgery. The presence of wax in the ear canal results in a conductive hearing deficit and will impact the monitoring data. If determined during the preoperative visit, the patient can be asked to clean their ears prior to surgery. If not discovered until the patient is seen in holding, then an ENT consult should be considered for wax removal prior to surgery or you may remove it yourself or ask the surgeon. The anesthetic regiment has little to no effect on the potential and it is the most robust to anesthesia and other systemic factors, and so any concerns or discussions with the anesthesia members of the team are more likely to focus on modalities other than the BAEP [8]. In the operating room, stimulation is usually provided through ear inserts, placed into the ear canal and connected to the electromechanical stimulator through relatively rigid tubing of a known length, and hence time-delay. The neuromonitorist in the operating room must therefore determine an acceptable location to place the stimulators that will allow them to move with the patient but out of the way of the surgeons. In practice I find affixing them to the Mayfield clamp the most reliable way of performing this important step of setup. Replacing the ear inserts if they fall out during a case can be difficult and is not going to win you much appreciation from the rest of the team.

Stimulation Clicks

Like most evoked potentials, the BAEP is a time-locked (and averaged) response to a given stimulus. In this case, the stimulus is a broadband click, generated by an electromechanical transducer. In the outpatient setting, the stimuli are pure tones of known frequency and are usually generated in the earpieces of headphones. The objective of the outpatient, clinical BAEP is to diagnose specific hearing deficits, while in the OR, the objective is to preserve gross hearing. This is the reason broadband clicks are used over pure tones in the OR. Since the large headphones are impractical in the operating room, they are replaced with small transducers and the click is delivered to foam ear inserts through stiff rubber tubing. The length of the tubing is known and therefore imparts a fixed and known delay between the electrical pulse that generates the click, which triggers the recording system, and the delivery of the click to the ear [15]. In most cases, this is a 1-ms delay. The tubing is stiff to allow for reliable delivery of the stimulus to the ear. Care must be taken that the tubing is not pierced which will reduce the amplitude of the delivered click or clamped or kinked which may prevent delivery of the click altogether [16]. It is always worth checking this tubing after positioning of the patient but before the drapes are placed. Once the inserts are placed sealing the ear canal with bone wax and placing waterproof adhesive tape over the ear will prevent fluid from entering. Each click is generated by the movement of a membrane in the transducer either toward or away from the eardrum. The direction of movement is controlled by simply changing the electrical current driving the transducer. Since the space between the membrane and the eardrum is enclosed and air cannot readily escape, movement of the membrane toward the eardrum condenses the air in that space. This type of click is therefore known as a condensation click. Similarly, movement of the membrane away from the eardrum will reduce the air pressure (making it more rarefied) and so is known as a rarefaction click. In practice, both types of click sound the same on a behavioral level. Some individuals show a better response to one form of the click or another, and in those instances the optimal form should of course be used. However, for many people, there is no difference in their response (at least meaning that good, monitorable signals can be obtained from either polarity), and so the choice is left to the person running the case . It has been noted that condensation clicks can enhance peak V while rarefaction clicks may enhance peak I. There is one further option available on most modern IOM and EP machines, and that is to alternate the clicks. Alternating clicks can sometimes improve the amplitude and discrimination of the peaks (see below) and it also removes or reduces the artifact substantially. The removal (or reduction) of the artifact has its supporters as well as its detractors. As ever, the artifact serves to confirm that a stimulus pulse has been applied, although in the BAEP it is possible to get an artifact with the ear tubes out of the ear since it is the electromechanical movement that generates the artifact. However, in general, the amplitude of the artifact will be an indicator of the amplitude of the stimulation (at least the electrical trigger to the electromechanical transducer).

Parameters

There are, with all evoked potentials, a number of parameters that can be varied for the BAEP. For the BAEP, these parameters are stimulation rate, stimulation amplitude, and the polarity of the clicks as discussed above. The stimulation amplitude, measured in decibels (dB), determines the size of the evoked potential recorded. This is not a linear response, however, as stimulation below the hearing threshold will not result in any response. Above that level increases in the amplitude will give an increase in the amplitude of the response. Conductive hearing deficits have a similar effect on the recorded responses as reducing stimulation intensity. Stimulation rate has a profound effect on the amplitude of the response. As ever with IOM, there is a desire for real-time recording and interpretation, and the BAEP can be recorded adequately with stimulation rates between 5 and 50 pulses per second (pps). So why do many groups tend to work toward the lower end of the spectrum? Especially as each patient is their own control and so there is no need to conform to laboratory standards. There is an optimum frequency that compromises between speed and quality of response. Above 10 pps, the response tends to lose amplitude so most clinicians work around the 10 pps range, avoiding of course exact multiples of the local line frequency. In the outpatient setting it is usual practice to stimulate one ear at a time, and consequently the other ear has white noise played into it to ensure that only one ear is tested at a time. During surgery both ears are tested at the same time (interleaved stimulation) and so there is no need to apply masking, white noise stimulation.

Recording

The recording settings for the BAEP in the operating room are similar to those in the outpatient clinics. The high-pass filter is typically set at 30 Hz but can be increased to 100 Hz if required to reduce line noise. The low-pass filter is set at 2 kHz or a similar frequency, depending on individual machine specifications. The small size of the cortically recorded responses dictates that the larger number of responses needs to be accumulated to typically obtain reliable and repeatable records. It is not uncommon to need 1000–3000 averages to obtain a quality signal.

However, with some optimization of the stimulus, environment, and recording conditions, it is possible to need less than 200 averages in some cases. There is considerable value in trying to use the fewest averages possible to get good responses [16].

Montages

The generators of the short-latency BAEP (see above) are all deep within the brain, and so in general the recording montage is actually relatively unimportant in IOM. Since the electrodes (hopefully) do not move during a case and the patient serves as their own control, there is some latitude in montage selection for IOM, but not in outpatient clinical practice [15]. Probably the most usual configuration is using three electrodes: the two ear lobes (A1 and A2) and the vertex (Cz). Since the generators of the peaks are all distant to these recording sites, it is obvious that the exact locations are not overly important. If I am only recording the BAEP, I do not measure the vertex, but am happy to locate that electrode by “eyeball” and to move it to accommodate surgical considerations . A common alternative to the ear lobe is to use the mastoid. In these instances, the recording montage is configured A1-Cz and A2-Cz. It is always worth displaying both the ipsilateral and contralateral derivations because of the bilateral projections within the pathway . Peak I will only be visible from ipsilateral recording (often termed Ai, i for ipsilateral and therefore Ac with the c for contralateral). In contrast, peak V is most clearly visible within the IV/V complex from the contralateral recordings.

Troubleshooting the BAEP

Within the field of IOM, the BAEP is probably the most robust signal that is recorded. Anesthesia has little to no effect on the waveforms, and temperature variations within the normal physiological range have no effect on the latencies, although cold irrigation may increase latencies for a brief period of time . Variations in blood pressure have little effect on the BAEP as well [8]. The aspects of surgery have significant effects on the BAEP though. As with most IOM signals, monopolar cautery prevents the recording of the signal and can in some instances lead to a short-term saturation of the amplifiers. Bipolar cautery can be used during recordings at times but will often lead to interference on the recordings. It is less common that amplifier saturation will occur with bipolar cautery, but it should always be considered a possibility if there is a sudden disappearance of the waveform [17]. With many of the surgical procedures for which the BAEP is warranted , there is a considerable amount of bone drilling to be performed. Interference from the high-speed drill is a result of the vibration of the bones within the skull including the bones associated with hearing and less so from any electrical interference if an electrical drill is used. For an accurate BAEP, the drilling must have ceased as the vibration may result in disappearance of all waves of the BAEP. It is important that this information is communicated to the rest of the team before the procedure commences. A further potential issue that occurs during bone drilling is the large amount of irrigation that can be used. This fluid can easily find its way into the ear and even through routes that seem highly unlikely. Fluid in the ear canal will result in an attenuation of the amplitude and increase in latency of peak I. The best solution for this problem is to prevent it from happening by trying to ensure that the ear canals are watertight before draping. As mentioned previously, care must be taken that the tubing between the ear inserts and transducers is patent and not kinked . The transducers do have some mass and will tend to pull down and so should be fixed to something that should move with the patient such as the head holder.

Interpretation and Alarm Criteria

The BAEP within the operating room has a number of measured and useful parameters. Both latency and amplitude are used as alarm criteria, but the alarm criteria will be specific for any given surgery . However some principles can be used as discussed below. The first parameter to be considered is the latency of peak I. This should be 1 ms, but the addition of ear inserts and tubing will normally add a further 1 ms to the latency for a total of 2 ms. Some IONM machines automatically include the 1 ms tube delay in the recordings, so as always check your machine. There may be delays to this peak at the commencement of the case, but these should not increase during the case. The amplitude of peak I is also measured and providing the stimulation does not change, should not change. A change may indicate a movement of the ear insert, kink in the tube or damage to the nerve. The latencies between peaks I and III and I and V (and therefore III and V) are all used as interpretive parameters. Because the peaks occur in a serial fashion for any given delay between peaks I and III, there should be the same delay between peaks I and V and no further delay added between peaks III and V. Although peak V is most easily identified in the contralateral recording (Ac-Cz), once it is identified there, it is usually identifiable ipsilaterally (Ai-Cz). This makes the latency identification relatively easy. If the peaks are identified at baseline, most modern IOM software will be able to track automatically the latencies throughout a case and alert the user when a threshold change in latency is reached. Similarly the amplitudes of peaks I, III, and V can also be tracked automatically if the peaks are identified appropriately at the commencement of the case [1]. Changes in both absolute latencies as well as changes in interpeak latencies are monitored. Conductive hearing loss or technical issues involving the stimulus not reaching the auditory nerve can cause changes in absolute latencies with no change in interpeak latencies. Intraoperative variability of interpeak latencies suggests sensorineural hearing damage or brainstem injury. A change in the interpeak latency from III to V and an absolute latency change of wave V are most concerning for brainstem ischemia as discussed below. The same principles apply to the BAEP as to most other evoked potentials in the operating room. A decrease in amplitude tends to indicate that less signal is getting through and an increase in latency indicates a slowing of the conduction velocity [1, 8]. There are a number of caveats to this general statement of course. For instance, a small increase in the conduction delay for the fastest fibers may result in a small increase in latency and a decrease in amplitude. However, the amplitude change may be a result of cancelation of some of the signals due to collision of waves, especially where more than one nucleus generates/contributes to a particular wave. Typically warning criteria are based upon the latencies of individual peaks and the interpeak latencies. An increase in the latency of peak V is considered the alarm for tumor dissection. There is very little “normal” trial to trial variability in the latencies of the peaks in the BAEP. Changes in the interpeak intervals can therefore be used to help identify the origin of the changes [8]. An isolated increase in the absolute latency of peak III in the absence of a change in peak I will lead to an increase in the I–III latency. If there is no change in the III–V latency, there will however remain an increase in the absolute latency of peak V. For this reason, it is therefore very important to keep track of not just the absolute latencies but also the interpeak intervals. The question then arises as to whether the absolute or relative latencies are the best parameters to monitor . However, as the brief example illustrates, using one or the other is not the best use of our resources and we do need to keep both in mind. Modern machines, especially if you can use a large monitor, allow for the display of tables of latencies and interpeak latencies (these are useful not just for BAEPs but other potentials). Such tables are, I find, the easiest way to track changes in these latencies and distinguish whether a change in the latency of peak V is solely due to changes in the latency of peak III. An alternative scenario, and one which is not uncommon in the case of large posterior fossa tumors, especially in the pediatric population, is that there is a global increase in the latencies. This is manifested as an increase in both the I–III latency and the III–V latency. Consequently, both peaks III and V are delayed, and the I–V interpeak latency is also increased. In these situations, the only change that might reach a critical level may be the absolute latency of peak V. However, it is wrong to therefore assume that there is a focal site of damage/injury along the III–V pathway. More likely there is a global change going on, possibly related to changes in blood flow or retraction/compression. Amplitude decreases are likely to be nonconsecutive in nature, meaning that a 25% change in peak I amplitude will not give the same change in peaks III and V. Monitoring the amplitude of all of the peaks is therefore still required and any change of more than 25% should be reported and discussed with the rest of the surgical team. Changes greater than 50% are worrisome. However complete absence of peak V has been reported in some individuals who do not experience hearing loss upon awakening, although some authors believe that they may be at higher risk of hearing loss subsequently. If peak I is absent , then all subsequent peaks will be absent. For this peripheral peak I use the more usual 10% change in latency and 50% decrease in amplitude criteria if the surgery is around this nerve. If brainstem function is mostly at risk , data trends not yet reaching significance should always be discussed with the surgical team.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree