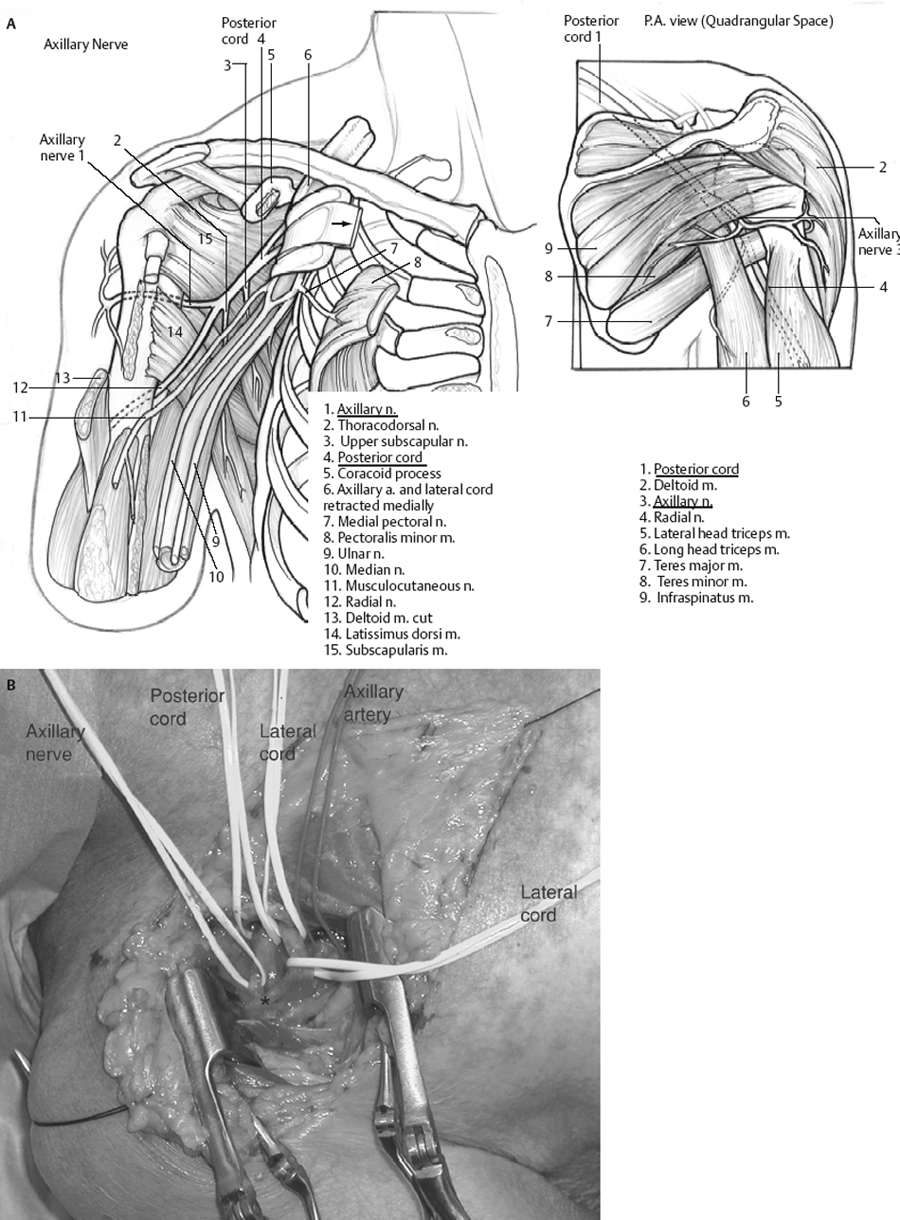

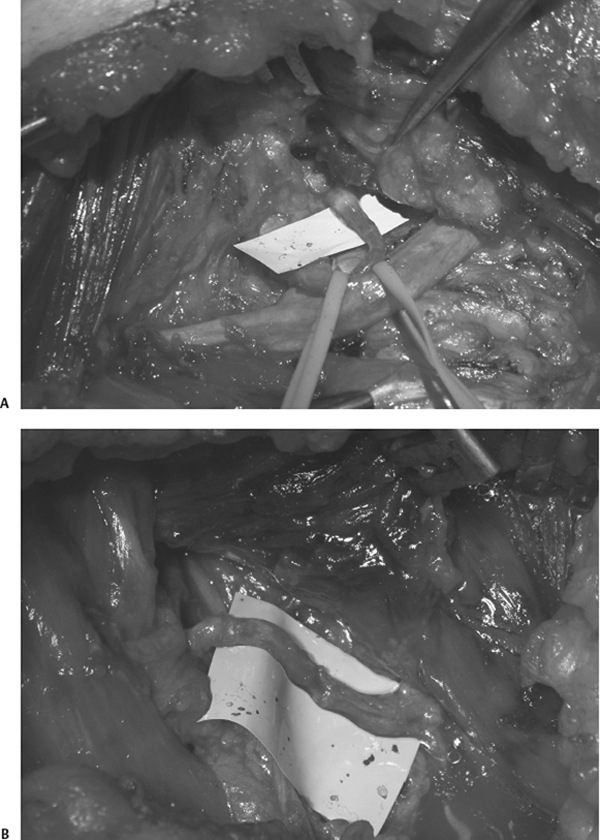

18 Axillary Nerve Injury and Repair A 19-year-old male involved in a motorcycle collision suffered a dislocation and ligamentous injury to his right shoulder requiring surgery. Preoperatively he is unable to abduct the arm at the shoulder (his exam is limited by shoulder pain), and he has severe but incomplete weakness of the triceps, brachioradialis, supinator, wrist and finger extensors, and long thumb abductor. There is sensory loss over the lateral upper arm. Postoperatively, he is able to initiate shoulder abduction and external rotation, and he begins a physical therapy program. An electrodiagnostic study at 3 weeks demonstrates a severe injury involving the posterior cord distribution, with evidence of preservation of radial nerve continuity. After 3 months, the patient has regained significant function in his extensor muscles; however, he continues to have complete deltoid paralysis. He is taken for posterior cord and axillary nerve exploration with intraoperative electrophysiological stimulation. At surgery the posterior cord has a large neuroma-in-continuity, which extends into the proximal axillary nerve. A nerve action potential (NAP) is successfully recorded across the posterior cord neuroma with the distal electrode on the radial nerve, but the NAP from the posterior cord to the axillary nerve is negative. The axillary nerve is sectioned serially until a healthy fascicular pattern is seen. The sural nerve is harvested and four cable nerve graft segments are placed using microsurgical technique. After initial immobilization in a sling for 3 weeks postoperatively, he resumes physical therapy. Posterior cord and axillary nerve injury The axillary nerve originates from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus at the level of the coracoid process and provides the motor innervation to the deltoid and teres minor muscles (Fig. 18–1 A,B). The nerve carries nerve fibers from the C5 and C6 roots. The nerve arises immediately posterior to the coracoid process and conjoined tendon. Following its origin, the continuation of the posterior cord becomes the radial nerve. The axillary nerve then crosses the inferolateral surface of the subscapularis, just medial to the musculotendinous border. It courses along the inferior border of the shoulder capsule and travels through the quadrangular (also known as the quadrilateral) space with the posterior circumflex humeral artery and vein. After passing through the quadrangular space, the nerve divides into anterior and posterior branches. The posterior branch provides innervation to the teres minor, the posterior part of the deltoid muscle, as well as the skin over the lower two thirds of the posterior part of the deltoid muscle and the long head of the triceps brachii. This is done as the posterior branch divides into three terminal branches: the nerve to the teres minor, the superior-lateral cutaneous branch, and the posterior branch to the deltoid. The anterior branch winds around the surgical neck of the humerus, beneath the deltoid, with the posterior humeral circumflex vessels, as far as the anterior border of that muscle, supplying it and giving off a few small cutaneous branches. The anterior branch also provides terminal sensory branches to the shoulder joint. Due to its location of branches deep within the deltoid muscle as well as its origin just next to the shoulder capsule, axillary nerve injury may occur in the course of dissection for anterior shoulder surgery or as a consequence of anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Also, because of its relatively fixed position at the posterior cord and at the deltoid, any downward subluxation of the proximal humerus can result in traction injury to the nerve. Although penetrating injuries of the shoulder may cause traumatic discontinuity of the axillary nerve, the large majority of axillary nerve palsies occur due to stretch injuries caused by blunt trauma or iatrogenesis. The clinical presentation of an axillary nerve injury is characterized by the lack of shoulder abduction greater than 30 degrees, with or without sensory loss of the lower two thirds of the shoulder. Patients do not often complain of decreased external rotation of the shoulder due to weakness in the teres minor because the infraspinatus muscle is dominant in that action. Commonly, patients are involved in blunt trauma and have a constellation of shoulder injuries, including anterior dislocation of the shoulder, humerus fractures, or multiple supraclavicular brachial plexus stretch injuries requiring shoulder immobilization, ultimately masking the lack of deltoid function secondary to axillary nerve injury. This is often discovered later, requiring diagnostic investigation of the deltoid innervation. Iatrogenic axillary nerve injuries are usually caused by extensive retraction of the anterior deltoid muscle during rotator cuff surgery or downward traction of an unstable shoulder or humerus fracture. Figure 18–1 (A) Illustration of the anatomy of the axillary nerve. (B) Cadaver dissection via an anterior infraclavicular approach through the deltopectoral groove, right side. Visible are the musculocutaneous nerve (black star) overlying the radial nerve (white star). (Reproduced with permission from Maniker AH. Operative Exposures in Peripheral Nerve Surgery. New York: Thieme; 2005:53, Fig. 5–8.) Deltoid muscle weakness can also be caused by injuries to neural elements more proximal to the axillary nerve. Injury to the C5 nerve root or spinal nerve, upper trunk, as well as the posterior division and cord can also cause deltoid weakness. In many of these cases patients may have weakness in muscles supplied by the radial nerve, also supplied by the posterior cord. Rotator cuff injury or arthropathies of the glenohumoral joint should also be investigated as possible impediments to active abduction of the shoulder. If severe nontraumatic shoulder pain followed by muscle atrophy and weakness is a significant part of the patient’s presentation, a generalized brachial plexitis (Parsonage-Turner syndrome) may also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Quadrilateral space syndrome, the formation of fibrous bands within the quadrilateral space causing axillary nerve compression, may also present with shoulder pain, but with a more gradual onset and chronic course. Suprascapular nerve injury will result in difficulty initiating arm abduction and external rotation, which should not be confused with axillary nerve injury. In some patients with dislocation or traction injuries involving the shoulder, both suprascapular and axillary nerves may be injured concomitantly. This results in complete loss of shoulder abduction and external rotation. Nevertheless, the clinician should maintain a high index of suspicion if deltoid weakness is temporally associated with shoulder trauma or surgical procedures of the shoulder or axilla. Electromyography (EMG) is very useful in determining if isolated axillary nerve injury is the cause of deltoid weakness, thus differentiating from more proximal neural pathology. Also, EMG may be employed to determine the extent of denervation or reinnervation of the deltoid after injury to guide surgical decision making. Orthopedic evaluation of the shoulder with plain x-rays and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should allow one to exclude joint pathology as a cause for immobility. In the case of penetrating trauma, a computed tomographic (CT) scan of the axilla may be useful in determining the path of the missile or knife as well as the presence of a possible compressive hematoma. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), computed tomographic angiography (CTA), or catheter angiography should be considered in these cases to identify associated vascular injury. Unless clean division of the axillary nerve is suspected, initial conservative management of the injury is recommended. For those patients who continue to have deltoid paralysis on examination and minimal improvement on follow-up EMG after 3 to 4 months from injury, surgical exploration and appropriate repair or neurolysis of the nerve should be performed to improve the patient’s chance for recovery of function. In cases where sharp division of the nerve is suspected, more expedient repair within 72 hours of the injury should be pursued. Surgical exposure of the axillary nerve can be done using a singular anterior infraclavicular approach, or in combination with a posterior approach for better visualization and circumferential repair of the nerve in the quadrilateral space. Adjunctive electrophysiological monitoring should be arranged to measure NAPs to guide the type of repair attempted. In the anterior infraclavicular exposure the patient is positioned supine with the arm slightly abducted to expose the deltopectoral groove and clavicle. An initial curvilinear incision is then made below the clavicle and continued just medial to the deltopectoral groove toward the axilla. The pectoralis major muscle is split in the direction of its fibers close to the deltoid, and the cephalic vein is either retracted or ligated and divided. The pectoralis minor muscle beneath is then divided at the coracoid process, and the lateral cord is identified within the underlying fat.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree