Benign Tumors of the Cervical Spine

Alan M. Levine

Stefano Boriani

Most patients who present with cervical spine pain, radiculopathy, or myelopathy are older than 40 years of age and eventually diagnosed with cervical spondylosis. However, a small number of predominantly younger patients are found to have a neoplasm in the cervical region. These neoplasms can be located in the paraspinal soft tissues, in the extraosseous or intraosseous bony portions of the spine, or in the intradural or extradural space with involvement of the neural elements. While the most common paraspinal tumors are soft tissue sarcomas, occasionally benign soft tissue lesions such as lipomas or schwannomas do occur in a paraspinal location. The most common subset of intraosseous bony lesions of the cervical spine in patients older than 40 years of age are metastases to the vertebral bodies, with or without soft tissue extension into the paraspinal region or extradurally into the spinal canal. If radiographs are not obtained initially, associated symptoms may easily be confused with those of cervical spondylosis even in a patient with a history of systemic malignancy. Of the primary bone tumors, benign lesions of the cervical spine are less frequent than malignant lesions (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7), in contrast to the remainder of the spine, where benign tumors are more common than their malignant counterparts (7). As with other benign bony spinal processes, however, these tumors occur predominantly in young patients. The final group of benign tumors of the cervical spine includes those involving the neural elements, which can either be intradural (e.g., meningiomas) or extradural (e.g., neurofibromas, schwannomas, and paragangliomas) (8).

Within this subset of benign spinal lesions, a number of different histologic types can be found, varying widely in their pathologic behavior. These range from minimally destructive and relatively avascular tumors (e.g., osteoid osteoma) to highly destructive and extremely vascular lesions (e.g., osteoblastoma or aneurysmal bone cyst [ABC]). Likewise, these tumors can range from small lesions occurring predominantly in the dorsal elements (2,5,9, 10, 11 and 12) to larger expansile masses within the vertebral body with or without expansion into the pedicles and the dorsal elements (12, 13, 14 and 15). Despite differences in pathology and size, they have many common features and present similar treatment problems resulting from their association with both neural and vascular structures in the neck. They also occur predominantly in patients in the second and third decades of life, further complicating even limited tumor resection in the cervical spine in this age group.

The diagnosis and evaluation of these lesions has changed dramatically in the past 20 years, first with the advent of computed tomography (CT) and more recently with the development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (16). In most series before 1980, major delays in diagnosis and treatment of benign tumors of the cervical spine were common because the only effective radiographic studies were plain x-rays and bone scans (2,9,10,13,17,18). For small lesions hidden in the complex anatomy of the cervical spine, plain radiographs even with multiple views were often insufficient to allow visualization of the lesion. The rapid expansion of imaging modalities including CT scan, MRI (19), single photon emission computed tomography bone scans, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography have made even the smallest lesions visible. More accurate definition of neural, vascular, and soft tissue involvement with noninvasive modalities has resulted in much earlier diagnosis and treatment for patients. Similarly, CT-guided biopsy frequently makes it possible to achieve a definitive histologic diagnosis without the morbidity or risk associated with open biopsy (1,20, 21, 22 and 23). Definitive imaging patterns, such as the characteristic “sclerotic rim and calcified nidus” appearance of an osteoid osteoma on CT or the “fluid-fluid” levels on the MRI of an ABC (20), make it feasible to plan surgery without biopsy, with the definitive diagnosis made intraoperatively by frozen section. The dimensional reconstruction of fine cut CT scans and even three-dimensional (3-D) modeling for surgical planning (24) can dramatically improve the quality of the surgical intervention.

Embolization, both as a definitive modality and as a preoperative adjunct, has decreased the operative morbidity associated with highly vascular lesions (11,25, 26, 27 and 28). Minimally invasive techniques such as percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can also effectively replace surgical excision in some cases (29,30). Advances in anesthesiology and intraoperative monitoring of motor- and sensoryevoked potentials have made it possible to perform surgical excisions of complex benign lesions more safely. Finally, although it may initially seem incongruous to consider treating a benign lesion with either radiation or chemotherapy, selective indications have appeared in the literature. Improvements in delivery techniques have made use of adjuvant treatments possible in the most complex or

recurrent cases (31,32). New technologies such as stereotactic radiosurgery provide alternative methods for treatment of patients whose tumors have either not responded to more conventional treatment or in whom the risks associated with surgical resection are excessive (8).

recurrent cases (31,32). New technologies such as stereotactic radiosurgery provide alternative methods for treatment of patients whose tumors have either not responded to more conventional treatment or in whom the risks associated with surgical resection are excessive (8).

Therefore, to care effectively for patients with benign tumors of the cervical spine, it is important to understand the patterns of presentation as well as the natural history and potential for progression of the various tumor types. Especially in the pediatric population, it is necessary to be able to inform parents of the expected response to treatment and the likelihood of recurrence, which may require additional procedures.

PATIENT POPULATION

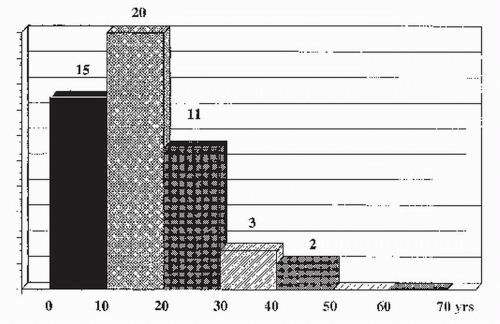

Although each tumor type has a slightly different age range and gender predilection, men are generally affected twice as often as women (6,7,9,26). For patients with ABCs, the male and female incidences are approximately equal (26,33). Both giant cell tumors and hemangiomas, on the other hand, show a slight female predominance and a peak incidence in the third decade (4,34,35). This finding is compatible with the occurrence of giant cell tumors throughout the remainder of the skeleton. Most other primary cervical tumors occur in a population younger than 20 years of age (Fig. 56.1) (7). Interestingly, this demographic profile fits patients with osteoid osteomas, osteoblastomas, ABCs, and osteochondromas most closely. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) (previously referred to as eosinophilic granuloma) may occur in a somewhat younger population (36, 37 and 38) but still with a male predominance.

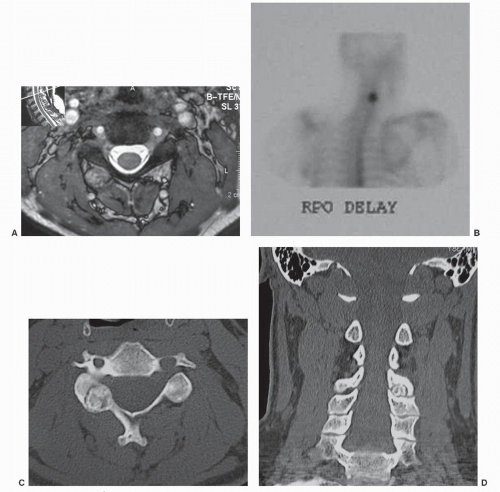

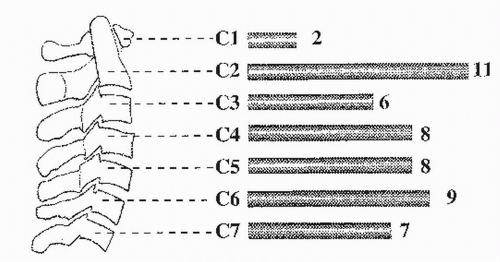

With each of the various histologic types of tumors, there is a relatively random occurrence of lesions within the various segments of the cervical spine. Few lesions occur in C1 (18), but the distribution from C2 to C7 shows slight variation from series to series (Fig. 56.2). Predilection for location within the vertebral elements is relatively specific for each tumor, as is the occurrence in the cervical spine versus the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions. Osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas occur predominantly in the dorsal elements of the spine, especially in the areas of the facet joints and pedicles (Fig 56.3) (3,13). Osteoblastomas and occasionally osteoid osteomas (39) can also arise in the ventral elements of the spine. About 25% of all spinal osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas occur in the cervical region, with predominance in the lumbar region (13,39,40). ABCs occur frequently in the dorsal elements, especially the spinous processes, lamina, and pedicles, and when the vertebral body is involved, the tumor is usually circumferential (5,19,25,26,33,41,42). As in the case of osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas, lumbar involvement is most common, while the cervical spine is the site of origin about half as frequently as the lumbar region. Osteochondromas were thought to be reasonably rare lesions, although two reports (43,44) have suggested that they are slightly more common than previously assumed. They can occur anywhere in the cervical spine and are more often found in males, occurring around the third decade of life.

Figure 56.1. Age distribution of 51 cases of benign tumors of the cervical spine observed at the Rizzoli Institute. |

Figure 56.2. Occurrence in the cervical spine of 51 cases of benign tumors observed at the Rizzoli Institute. |

LCH (previous referred to as eosinophilic granuloma) typically involves the vertebral body and only rarely the pedicles and dorsal elements, even in multifocal and advanced cases. The lumbar and thoracic spines are much more commonly affected than the cervical spine. For uniformity, the nomenclature for this tumor has recently been changed by the World Health Organization. The eponymic terms, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease and Letterer-Siwe disease, have been dropped in favor of the term multicentric bone and systemic involvement. The patterns of vertebral involvement are similar in all forms of the tumor.

Giant cell tumors were the fourth most common benign tumor in the spine in Dahlin and Unni’s series (45), but more than half of those tumors occurred in the sacrum. About 5% of all giant cell tumors occur in the spine with predominant involvement in the vertebral body. Within the mobile spine, a cervical site of origin is as common as a thoracic or lumbar location. Other tumors can also occur in the cervical spine, such as osteoma (46,47), chondromyxoid fibroma (48), or fibrous dysplasia (49), but so infrequently that characterization of the patterns of vertebral involvement are not relevant.

DIAGNOSIS

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The clinical onset of primary benign tumors of the cervical spine is usually nonspecific (6,7,50, 51, 52 and 53) and typically consists of either diffuse or localized neck pain. The pain

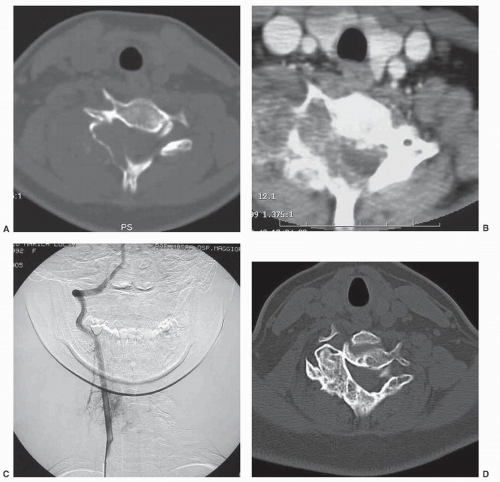

in some cases is constant and in other cases episodic, but usually, it is localized in asymmetric lesions to the involved side of the neck. In osteoid osteomas, the pain is nocturnal in about 50% of patients and is relieved by the use of salicylates in 30% of cases (15,54, 55, 56, 57, 58 and 59). When a tumor, such as an osteoid osteoma or osteoblastoma, encroaches on a neuroforamen, radicular symptoms and signs may be present. Myelopathy from dural sac compression is extremely infrequent, although it can occur with more aggressive tumor types such as giant cell tumor (60), ABC, or osteoblastoma (61,62). On the other hand, most hemangiomas of the spine are asymptomatic. However, when they are symptomatic, the presentation is highly variable and usually associated with muscle spasm (4,54,63, 64 and 65). Tumors that preferentially involve the vertebral body as opposed to the dorsal elements, such as giant cell tumors (60), LCH, and ABCs (19,53), often present with constant pain or neurologic injury (Fig. 56.4), especially when associated

with pathologic fracture and collapse of the vertebral body (53,66). Exophytic tumors may occasionally cause dysphagia due to esophageal compression. As previously mentioned, in a large series of benign cervical tumors (7), the duration of symptoms averaged 19 months but ranged from 1 to 60 months; however, some patients in this series did not benefit from current methods of evaluation. Even so, those patients with LCH and ABCs had relatively short symptomatic periods as a result of the severity of pain complaints. More current series suggest that the average duration of symptoms in the adolescent population with neck pain averages less than 2 months and that neck pain and muscular spasm are the most common presenting symptoms, while torticollis can also occur (7). Presentation with a mass is relatively rare, but patients with osteochondromas and ABCs involving the dorsal elements may exhibit that finding. Even with the advanced imaging, which is now readily available, the duration of time to diagnosis of some small lesions, such as osteoid osteoma, may still be prolonged.

in some cases is constant and in other cases episodic, but usually, it is localized in asymmetric lesions to the involved side of the neck. In osteoid osteomas, the pain is nocturnal in about 50% of patients and is relieved by the use of salicylates in 30% of cases (15,54, 55, 56, 57, 58 and 59). When a tumor, such as an osteoid osteoma or osteoblastoma, encroaches on a neuroforamen, radicular symptoms and signs may be present. Myelopathy from dural sac compression is extremely infrequent, although it can occur with more aggressive tumor types such as giant cell tumor (60), ABC, or osteoblastoma (61,62). On the other hand, most hemangiomas of the spine are asymptomatic. However, when they are symptomatic, the presentation is highly variable and usually associated with muscle spasm (4,54,63, 64 and 65). Tumors that preferentially involve the vertebral body as opposed to the dorsal elements, such as giant cell tumors (60), LCH, and ABCs (19,53), often present with constant pain or neurologic injury (Fig. 56.4), especially when associated

with pathologic fracture and collapse of the vertebral body (53,66). Exophytic tumors may occasionally cause dysphagia due to esophageal compression. As previously mentioned, in a large series of benign cervical tumors (7), the duration of symptoms averaged 19 months but ranged from 1 to 60 months; however, some patients in this series did not benefit from current methods of evaluation. Even so, those patients with LCH and ABCs had relatively short symptomatic periods as a result of the severity of pain complaints. More current series suggest that the average duration of symptoms in the adolescent population with neck pain averages less than 2 months and that neck pain and muscular spasm are the most common presenting symptoms, while torticollis can also occur (7). Presentation with a mass is relatively rare, but patients with osteochondromas and ABCs involving the dorsal elements may exhibit that finding. Even with the advanced imaging, which is now readily available, the duration of time to diagnosis of some small lesions, such as osteoid osteoma, may still be prolonged.

Neurologic signs and symptoms can be characterized as either radicular (relatively frequent) or myelopathic (relatively infrequent). Radicular pain has been reported to occur in 20% to 50% of all patients; however, demonstrable radicular findings, such as changes in reflexes, sensation, muscle strength, muscle atrophy, or paresis, occur in fewer than 20% of cases. In more aggressive tumors, cord compression from either tumor extension or from pathologic fracture of the vertebral body has been reported to occur (27,27,49,60,62,66,67), but it is a more frequent finding in the thoracic spine (4,13,51). Circumferential vertebral involvement, as occurs in hemangiomas (63, 64 and 65) and ABCs (5,12,68), may cause gradual constriction of the neural canal and myelopathy. Likewise, in a patient with multifocal hemangiomas (about one-third of all cases) or in the setting of pregnancy, the prevalence of neurologic deficit is higher.

IMAGING STUDIES

The radiographic evaluation of any spinal lesion, and especially those in the cervical spine, begins with plain radiographs. At least two orthogonal views are necessary (anteroposterior [AP] and lateral). Although plain radiographs may identify the location of the lesion, a bone scan, CT, or MRI will provide further detailed information on the tumoral architecture, as well as the adjacent bony and soft tissue structures (69). PET scans are rarely indicated in the workup of suspected benign cervical tumors. Symptoms that should suggest further studies after an apparently negative plain roentgenogram are dysphagia, persistent nocturnal cervical pain, muscular spasm not relieved by medication, painful torticollis, radiculopathy, sudden occurrence of neurologic symptoms, and extremity pain, which may or may not fit a dermatomal distribution. Any patient with persistent neck pain unresponsive to conservative measures after 1 month in the setting of negative plain radiographs should be considered for a bone scan or MRI, depending on the clinical circumstance.

Plain Radiographs

A standard radiographic series to evaluate the cervical spine for the presence of a tumor should consist of an AP and lateral view. If the physical examination suggests symptoms at the craniocervical junction, an open-mouth view of the odontoid should also be obtained. Likewise, pillar or oblique views can help define a lesion located in the pedicles or facet joints. Because of the complex anatomy of the cervical spine and multiple overlapping structures, the plain radiograph may appear normal in smaller lesions. Despite this limitation, specific tumors may have a typical appearance. For example, exostoses are ossified and lobulated masses (46,47), while hemangiomas have a striated or honeycomb pattern. Osteoblastoma, alternatively, produces enlargement of the vertebral borders and is often associated with granular ossifications, whereas osteoid osteoma (when visible) has a radiolucent nidus with a variable ossified reaction. Fibrous dysplasia causes gross deformation of the bony outline with architectural derangement of cancellous bone and frosted-glass pattern. The later stages of LCH may have the distinctive appearance of vertebra plana. Conversely, ABCs and giant cell tumors appear predominantly as radiolucent areas with variable margins and are often difficult to distinguish on plain radiographs.

Bone Scan

Technetium-99m (99mTc) isotope labeling is of great value in detecting many tumors not visible on standard radiographs. Most benign cervical lesions are evident on bone scan. The only lesion that in its early stages may not exhibit intense activity is LCH, which becomes more evident after collapse of the vertebral body. Activity on99mTc may be faint and visible only on a SPECT scan until pathologic fracture has occurred, resulting in vertebra plana on plain radiograph. The most common benign lesion that can be symptomatic but not readily visible on plain roentgenogram is osteoid osteoma; however, osteoid osteomas are easily detected as a typical “hot spot” on bone scans (see Fig. 56.3B), while osteoblastomas result in larger hyperactive areas. ABC may present as a negative area with a positive border. On the other hand, the specificity of bone scan is minimal as fractures, infections, and osteoarthrosis can provoke increased uptake as well.

Computed Tomography

The CT scan is highly sensitive for early bone destruction and remains unsurpassed for both evaluation of, and planning for, surgical intervention for a benign lesion of the cervical spine. For bony lesions initially detected on either plain radiograph or bone scan, the next step for accurate definition of the lesion is axial CT images as cross-sectional views help to enhance the understanding of the inherently complex anatomy of the cervical spine. CT imaging is the best modality for evaluating cortical lesions and matrix calcification. For small lesions in the cervical spine or for accurate sagittal and coronal 2- or 3-D reconstructions, 2-mm axial slices are necessary through the area of interest. Use of both bone and soft tissue windows allows definition of not only the extent of vertebral involvement but also the presence or absence of a soft tissue mass, as well as an evaluation of vertebral artery, nerve root, or spinal cord involvement. Contrast enhancement can be used for assessment of the tumor margins and its intrinsic vascularity. Some CT images are considered pathognomonic, such as the calcified nidus in osteoid osteoma. Other highly suggestive findings include “polka dot” or “corduroy” patterns typical of hemangioma or the granular ossifications within a lytic area in osteoblastomas (16). CT can also be processed into 3-D models for preoperative planning (24). CT imaging, with or without the additional of myelography, is also of critical importance in patients who have a medical contraindication to MRI.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

For detecting occult lesions not visualized on standard radiographs, MRI has greater sensitivity than bone scan or CT imaging. Compared with normal bone marrow, most tumors demonstrate decreased signal intensity on T1-weighted images and increased signal on T2-weighted

sequences (16,70). MRI is rarely necessary in the initial evaluation of benign lesions of the cervical spine because other studies are more readily available and serve as better screening tools in the initial assessment of these patients. The MRI is a useful tool for completing the evaluation of tumors that may have a major soft tissue mass (giant cell tumor), involvement of the vertebral artery (giant cell tumor, ABC), or compression of adjacent nerve roots or thecal sac. MRI is particularly useful as it allows detailed noninvasive evaluation of soft tissue structures, which once required either angiography or myelography. The interpretation of the MRI must be considered together with other modalities to avoid incorrect diagnosis. For example, on MRI, the nidus of a small osteoid osteoma may remain undetected while the surrounding reactive area can be interpreted as a permeative infiltration into the cancellous bone (see Fig. 56.3A).

sequences (16,70). MRI is rarely necessary in the initial evaluation of benign lesions of the cervical spine because other studies are more readily available and serve as better screening tools in the initial assessment of these patients. The MRI is a useful tool for completing the evaluation of tumors that may have a major soft tissue mass (giant cell tumor), involvement of the vertebral artery (giant cell tumor, ABC), or compression of adjacent nerve roots or thecal sac. MRI is particularly useful as it allows detailed noninvasive evaluation of soft tissue structures, which once required either angiography or myelography. The interpretation of the MRI must be considered together with other modalities to avoid incorrect diagnosis. For example, on MRI, the nidus of a small osteoid osteoma may remain undetected while the surrounding reactive area can be interpreted as a permeative infiltration into the cancellous bone (see Fig. 56.3A).

Angiography

Angiography alone is rarely used as a primary tool to evaluate the vascularity of a lesion or to aid in diagnosis (71) because magnetic resonance angiography or CT angiography are less invasive and easier to obtain. Today, angiography is used primarily for selective vascular studies prior embolization. Embolization can then be performed either as a primary therapeutic modality (see case of an ABC treated with multiple selective embolizations over a 4-year period (Fig. 56.4) or in cases of Boriani et al. (25) giant cell tumors, or hemangiomas) or as a preoperative adjunct to decrease the vascularity and the surgical morbidity of these lesions (27). The shared branches to the tumor and spinal cord make embolization technically more difficult in the cervical spine than in the thoracic or lumbar regions. For the purpose of angiographic studies, the cervical spine should be divided into the upper cervical (C1 to C3) and the lower cervical regions (C4 to C7). A variety of arteries are typically evaluated, including the vertebral, occipital, ascending pharyngeal, thyrocervical, and costocervical arteries, assessing for such characteristics as arteriovenous (A-V) shunting that is more characteristic of malignant tumors. Embolization of benign lesions can be curative for giant cell tumors and aneurysmal bone cysts or palliative as symptoms such as pain may be reduced and tumor growth retarded following treatment. The type of embolization is based on the flow characteristics and the size of the lesion. Gelfoam, polyvinyl alcohol particles, stainless steel coils, n-butyl cyanoacrylate, and onyx (ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide) are the most commonly used substances. Embolization preoperatively should be done within 24 hours of surgery to achieve maximal effect and prevent revascularization of the tumor prior to surgical intervention.

BIOPSY TECHNIQUES

The complications of biopsy of bone and soft tissue lesions are myriad and documented (21,51). Clearly, the hazards are more substantial in malignant tumors than in benign ones irrespective of the location; however, even biopsy of benign lesions can be complicated by seeding of the tumor in the biopsy tract (e.g., giant cell tumor) or by excessive bleeding (e.g., ABC). Therefore, the basic principles of tumor biopsy should be followed strictly and include (a) placing the biopsy tract in line with the incision for definitive treatment, (b) achieving minimal tissue contamination by avoiding dissection of tissue planes, (c) obtaining adequate tissue for diagnosis (and confirming by frozen section that the tissue is viable and satisfactory for diagnosis), (d) obtaining adequate hemostasis to prevent contamination by hematoma, and (e) draining all open biopsy wounds. Following the basic criteria for correct biopsy technique are important in all musculoskeletal biopsies (3,72) but may be more difficult to adhere to in the spine as a result of the limited number of approaches and the proximity to critical neurovascular structures.

Biopsies of benign lesions of the cervical spine vary by the location, size, nature, and definitive therapy of the spinal tumor. Biopsies can be performed via a needle, incisional, or excisional approach. Needle biopsies are either a fine-needle aspiration or a core biopsy. In lesions in which the radiographic picture is characteristic and the lesion is relatively small, an excisional biopsy is safe and efficacious. In a larger lesion that has a soft tissue component for which surgery is being considered, an incisional biopsy followed by a frozen section is recommended. In lesions that have a soft tissue component and may not require surgical treatment or may be part of a larger differential diagnosis, a needle aspiration under CT or ultrasound guidance may provide sufficient pathologic material. This is often true of in the case of LCH or when trying to differentiate infection from tumor (1).

The approach to ventral lesions in the cervical spine is through a lateral entry point with a metal maker placed on the skin and a trajectory constructed to safely reach the lesion (Fig. 56.5). If a larger-bore needle is required, a ventral approach can be used in the upper cervical spine by traversing the thyroid gland. In the lower cervical spine, the needle is introduced just dorsal to the border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle with manual displacement of the carotid sheath ventrally. For lesions in the dorsal aspect of the cervical spine, biopsy using CT guidance greatly reduces the complexity of the procedure. Depth of biopsy and avoidance of both the spinal canal and the vertebral artery can be accomplished in this manner. CT guidance reduces morbidity and frequently makes it possible to reach even small lesions. Even in suspected benign cervical tumors, the preoperative biopsy allows adequate staging of the tumor and thus planning of the surgical reconstruction. The only contraindications to this technique include thrombocytopenia and extremely vascular lesions in which obtaining hemostasis after biopsy may be difficult. In the literature, the reported success rate of needle biopsies of the spine varies considerably from 50% to 90%. This rate is dependent on whether the series included biopsies of all regions of the spine and all tumor subtypes. Ottolenghi et al. (23) in 1964 was the first to report a series of cervical aspiration biopsies with a 79% success rate; later series have reported higher success rates (23). The most common adverse outcome of needle biopsy of the spine is

obtaining a nondiagnostic sample, or nonrepresentative tissue in heterogenous lesions.

obtaining a nondiagnostic sample, or nonrepresentative tissue in heterogenous lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree