Chapter 123 Bone Graft Harvesting

Bone Graft Specifications

Autograft

Autografts are commonly used in spine surgery, and they remain the gold standard for fusion. An ideal autograft should include strong cortical bone for structural support and cancellous bone for more rapid incorporation and fusion.1 Revascularization of cancellous bone is completed within several weeks, whereas the same process takes several months, or longer, for cortical bone.2,3 Autografts commonly are used in conjunction with spinal instrumentation, but can also be used for dorsal onlay fusions without instrumentation. A significant advantage of autologous bone is that there is no risk of disease transmission.

Allograft

Allografts are commercially prepared and typically are obtained from cadaver bone. They are characterized by delayed vascularization and incorporation, which is believed to be due to antigenic recognition by the host. Allografts are appropriate in a variety of clinical situations.4,5 They are most commonly used for ventral cervical interbody fusions, where single-level allografts generally lead to solid arthrodesis, similar to the fusion rate with autograft.6 However, they incorporate relatively slowly,7 and, if used for multilevel fusions, are associated with a pseudarthrosis rate of 63% to 70%.7,8 Fibular allografts are preferred for cervical corpectomy, because the harvesting of a fibular autograft is associated with significant morbidity, including pedal edema, ankle pain, and the risk for peroneal nerve injury.5

Bone Graft Substitutes

Nonbiologic materials such as hydroxyapatite,9,10 ceramic, and polymethylmethacrylate11 also have been used, either in conjunction with, or in lieu of, of bone graft materials. They have the advantage of being able to be manufactured in a variety of sizes, shapes, and quantities. Polymethylmethacrylate is an inert substance that is rarely used, except in cases where life expectancy is severely limited, as in providing structural support in a patient with metastatic disease to the spine and a very short survival.

Bone Graft Types

Local Bone

Bone that is removed during surgical decompression commonly is used in spinal fusions. It consists of both cancellous and cortical components. It can be morselized manually with a rongeur or can be placed in a bone mill to provide a more consistent substrate for grafting.12 The quality of local bone generally is perceived as being not as good as iliac bone grafts because of its cortical content.

Iliac Crest

The most commonly used donor site is the iliac crest. The iliac crest is a readily available source of cancellous bone, which provides rapid incorporation. Its disadvantages include donor site pain, which is a common complaint13; limited volume, which can be a concern for procedures requiring a copious amount of bone; and limited utility for procedures requiring a large piece of structural bone for reconstruction.

Ventral Iliac Crest Grafts

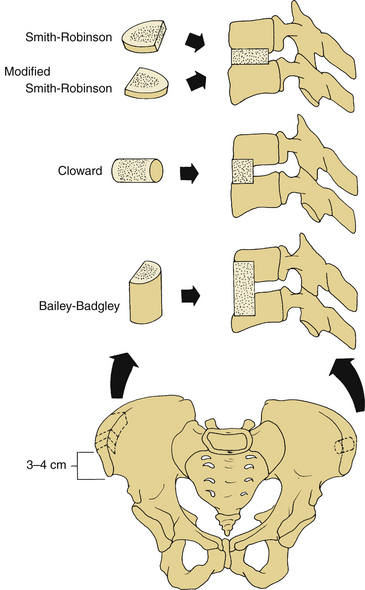

Ventral iliac crest grafts commonly are used to provide bone for various types of ventral cervical fusions (Fig. 123-1). The incision should be just caudal to the crest, to minimize discomfort that would be caused if the incision lay directly over the graft site, and should be placed approximately 3 to 4 cm lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to minimize the risk of inadvertent injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. This nerve lies lateral to the ASIS in 90% of patients; in 10% it lies medial to the ASIS. When harvesting a tricortical graft for anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, an incision 6 to 8 cm long and a subperiosteal dissection of both the inner and outer wall of the ilium are performed. The iliac crest also can serve as a source of structural graft for cervical corpectomy and can provide an 8- to 10-cm length of tricortical strut graft.14–17 Dissection of the iliacus muscle from the inner wall of the crest should be minimized to reduce the risk of hematoma formation and to reduce the risk of postoperative pain. The fascia should be closed meticulously to prevent a herniation of the pelvic contents.18,19

Dorsal Iliac Crest Grafts

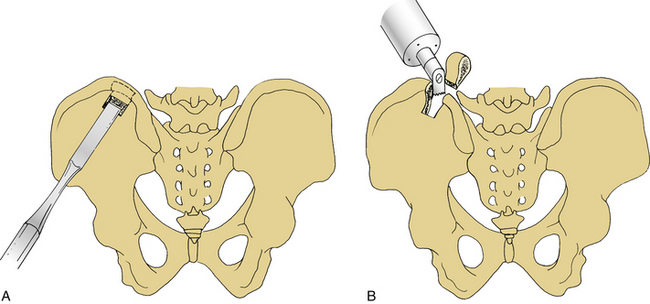

The dorsal iliac crest is predominantly used to obtain large quantities of dorsal onlay graft material for dorsolateral lumbar fusions. More bone is available from the dorsal iliac crest than from the ventral crest.20 Bone graft may be obtained through the midline lumbar skin incision used to perform the concomitant decompression or through a separate lateral skin incision over the iliac crest. The midline skin incision usually is used to obtain dorsal iliac graft. The optimal site for the underlying fascial incision is 6 to 8 cm lateral to the midline. If the fascial incision is placed lateral to this point, injury to the cluneal nerves may occur, which can result in numbness or pain over the buttocks. This is more likely if a large graft is required. Laterally, the sacroiliac ligaments and joints must be avoided. Care should be taken to minimize the depth of the osteotomy to avoid the sciatic notch where the superior gluteal artery and nerve could be injured. Injury to these structures is unlikely if the dissection is performed subperiosteally. Cancellous bone can be harvested with a gouge, which is helpful in removing strips of cancellous bone (Figs. 123-2 and 123-3).

Fibula

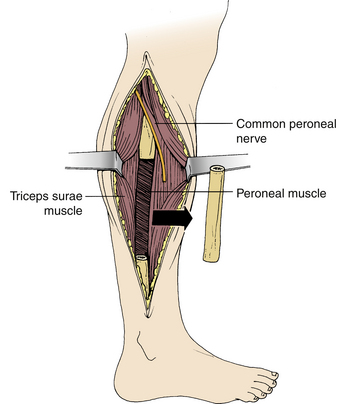

The fibula has the advantages of providing strength and length, and being relatively easily harvested. Its disadvantages include a slow rate of incorporation and harvest site complications. A fibular strut graft should be harvested from the middle third of the fibular shaft through a long skin incision on the lateral side of the leg, extending through the lateral intermuscular septum, preserving the periosteum (Fig. 123-4). During fibula graft harvesting, the peroneal nerve must be protected. Distally, the fibula should be harvested no more than 10 cm proximal to the ankle joint to minimize the risk of injury to the ankle syndesmosis, which is important for the stability of the ankle joint. The peroneal muscles should also be preserved. The middle third of the fibula should be osteotomized using an oscillating saw rather than an osteotome, which could cause fracture of the graft (Fig. 123-5). After fibula harvest, a few days of compressive leg wrapping with elevation of the leg will minimize swelling and discomfort.

FIGURE 123-5 Fibula graft harvesting. The midportion of the fibula is removed with an oscillating saw.

Care must be exercised when harvesting a long segment of fibula to avoid proximal extension of the graft to the region of the neck of the fibula, where the common peroneal nerve is in jeopardy of injury. Injury to this nerve may result in pain and weakness in the foot and ankle.21

Tibia

The subcutaneous ventromedial aspect of the tibia historically has been a site used occasionally for bone grafting. Currently, it is rarely used, because other, more suitable, autogenous or allograft alternatives exist. The potential morbidity associated with tibial grafts is significant, with tibial fracture being its main disadvantage. The tibia must be protected for several months to prevent fracture.22

Rib

Rib can be easily harvested, especially during thoracic spine operations. It is, however, a weak, poorly vascularized graft. Biomechanically it is inferior to the fibula. If taken with its artery, it is suitable for use as a vascularized strut graft.23–25 It is used almost exclusively with thoracic or thoracolumbar fusions.

Complications of Graft Harvesting

Graft harvesting complications are common, and pain from a bone graft harvest site sometimes is more severe than the pain from the actual surgical procedure.18,26–33 Although the complications usually are minor, a review of 1244 cases from multiple series demonstrated that their occurrence is about 20%, whereas only a 0.2% complication rate was reported at the neck incision site.34

Chronic Pain

Graft donor site pain is nearly universal in the early postoperative period13 but may be persistent in up to one third of patients35,36 and may continue throughout the first 3 months postoperatively in up to 15% of patients.29 One study reported that donor site pain was present for more than 10 years following surgery in more than one third of patients.36 The reason for this chronic pain is not well understood, but it often is associated with the patient’s overall pain syndrome. In addition, there are specific reasons for chronic donor site pain, including sacroiliac joint disruption, hernia through the graft site, fracture at the graft donor site (predominantly on the ventral ilium), and heterotopic bone formation.37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree