2Vancouver Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Brachial Plexopathy

Brachial Plexus Anatomy

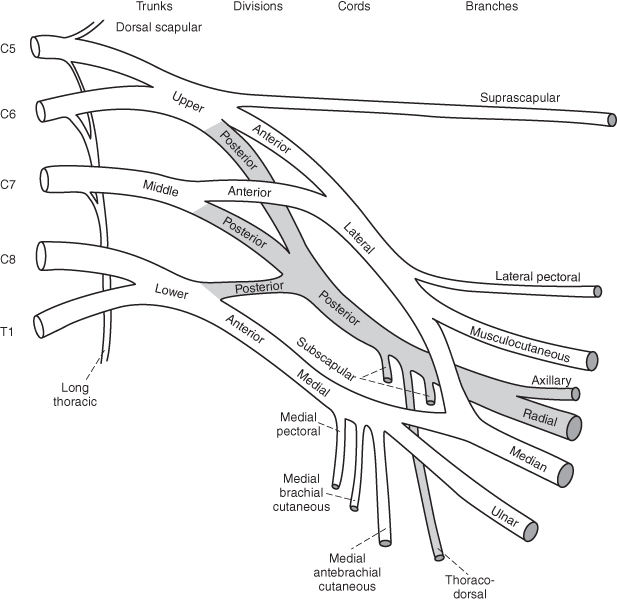

The brachial plexus is a complex network of nerve fibers that supply the upper limb (Figure 28.1). The ventral rami (roots) merge to become the upper (C5, C6), middle (C7), and lower (C8, T1) trunks. The trunks divide into anterior and posterior divisions. The divisions regroup to form the lateral, posterior, and medial cords. The cords form the five major terminal branches of the upper limb: the musculocutaneous, median, ulnar, radial, and axillary nerves.

tips and tricks

tips and tricks

“Run to drink cold beer” is a mnemonic that can be used to remember the basic anatomic organization of the brachial plexus: roots, trunk, divisions, cords, branches.

Figure 28.1. Anatomy of the brachial plexus.

(Reproduced from Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for Surgeons, Vol 3. The Back and Limbs, 2nd edn, New York: Harper & Row, 1969, with permission from Harper & Row.)

Trauma

Traumatic injuries are the most common cause of brachial plexopathy. Motorcycle or automobile accidents, knife or gunshot wounds, iatrogenic injuries, obstetric injury, and other stretch injuries can result in brachial plexopathy.

Rarely, the whole plexus is injured due to severe trauma. The entire arm is paralyzed and muscles undergo rapid atrophy. There is usually complete anesthesia of the arm with sparing of the medial upper arm (T1 innervated). The arm is areflexic.

The upper plexus (C5, C6 fibers) is predominantly affected when the head is pushed forcefully away from the shoulder. The arm may be internally rotated and adducted, the forearm extended and pronated, and the palm facing out and backward in the “porter’s tip” position (Erb’s palsy). Sensation over the deltoid region may be impaired. The biceps and brachioradioalis reflexes are affected.

Lesions to the middle trunk are rare but occasionally occur with trauma, resulting in primarily radial nerve involvement with weakness of the C7 extensors of the forearm, hand, and fingers. The triceps reflex may be depressed. Sensation over the dorsum of the forearm and hand may be reduced.

When the arm and shoulder are pulled upward, the lower plexus (C8, T1 fibers) is stretched. The patient has weakness of the intrinsic hand muscles and wrist/fingers (Déjerine-Klumpke’s palsy); a claw hand deformity may develop. Sensation may be altered over the medial arm and ulnar aspect of the hand. If the first thoracic root is injured, the sympathetic nerve fibers may be involved, resulting in ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome (ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis).

tips and tricks

tips and tricks

- Timing of electrodiagnostic testing (EMG): It is best to delay neurophysiological testing for 10–14 days after an acute nerve injury, to allow time for Wallerian degeneration to occur. Axonal loss results in the loss of amplitude in motor responses and denervation potentials on electromyography (EMG).

- Primarily neuropraxic injuries (which have a better prognosis for earlier recovery) can be distinguished from injuries with axonal loss.

- A plexopathy can be distinguished electrophysiologically from a radiculopathy: sensory responses are affected in plexopathy (a postganglionic injury) but not in radiculopathy, and EMG of the paraspinal muscles may be abnormal in radiculopathy but not in plexopathy.

tips and tricks

tips and tricks

timing of surgical referral

Preganglionic lesions and nerve root avulsion have no potential for spontaneous recovery, so early surgical intervention is warranted to maximize functional recovery. Nerve transfers (neurotization) can be performed to accelerate recovery from preganglionic injuries.

For postganglionic injuries, conservative management for the first 3–5 months will allow any element of neurapraxia to resolve and permit axonal regeneration to occur beyond the point of injury. If there is no evidence of muscle reinnervation at that time, surgical exploration is recommended. Postganglionic neuromas or ruptures may benefit from nerve grafting.

Acute Brachial Plexus Neuropathy

Idiopathic

Idiopathic acute brachial plexus neuropathy (ABN) is caused by an autoimmune-mediated attack on the plexus. Also called brachial neuritis, ABN has a reported annual incidence of 2–3 per 100 000 but is likely underrecognized. Over half of patients with ABN report an antecedent event, which can include infection or immunization.

Patients report acute, severe pain in the cervical, retroscapular region or shoulder, lasting from days to weeks. The acute pain is followed within weeks by rapidly progressive weakness and atrophy of the affected muscles. The distribution of affected muscles is characteristically “patchy.” Phrenic and cranial neuropathies (nerves IX, X, XI, and XII) can occur. Sensory changes are often mild. ABN is typically unilateral, but may be bilateral in 10–30% of cases.

Nerve conduction studies (NCSs)/EMG demonstrate axonal involvement in most cases. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine rules out a surgically remediable cause of radiculopathy, but imaging of the plexus is typically normal. If there is a positive family history, or a history of compressive neuropathies, genetic testing for hereditary neuropathy with predisposition to pressure palsies (HNPP) can be considered. The initial acute pain is often severe and should be aggressively treated; often a combination of anti-inflammatory, neuropathic medication and opiate analgesics is needed. Early implementation of physical therapy to prevent frozen shoulder is important. Current treatment recommendations are given in Box 28.1.

Box 28.1. Current treatment recommendations for acute brachial plexus neuropathy

- Pain management often requires a combination of neuropathic pain medication, an anti-inflammatory, ± an opioid analgesic. Options for neuropathic pain treatment include nortriptyline 10 mg, titrated to 40 mg, or pregabalin 75 mg twice daily titrated to 150 mg twice daily

- Early physical therapy to maintain range of motion

- Consider prednisone 60 mg day for 7 days, followed by tapering dose by 10 mg/day for 5 days, initiated within the first month after symptom onset to improve strength and possibly reduce duration of pain if no contraindications exist

evidence at a glace

A systematic Cochrane Review found only anecdotal evidence on intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), intravenous steroids, and plasmapheresis in the treatment of neuralgic amyotrophy. There is currently no evidence from randomized trials on any form of treatment for neuralgic amyotrophy. A prospective, randomized trial is under way.

Most patients show significant improvement. However, in a large series of 246 patients with ABN, almost a third had chronic pain, and most patients had some persisting functional deficits at 6-year follow-up. The recurrence rate is reported to be between 5 and 26%, with a median time to recurrence of 2 years.

tips and tricks

tips and tricks

The distribution of weakness in acute brachial plexus neuropathy is often patchy. Commonly affected nerves include:

- Suprascapular nerve → supra- and infraspinatous muscles → weak shoulder abduction/external rotation

- Anterior interosseous nerve → inability to do the “OK sign” with the fingers

- Long thoracic nerve → serratous anterior muscle → scapular winging

- Axillary nerve→ deltoid muscle → weak arm abduction

- Phrenic nerve → diaphragm muscle → dyspnea, elevated hemidiaphragm on imaging

Hereditary Brachial Plexus Neuropathy

Hereditary brachial plexus neuropathy (HBPN) is a rare, autosomal dominant condition characterized by recurrent, painful brachial neuropathy. Mutations in the SEPT9 gene on chromosome 17q25 have been identified. Minor dysmorphic features can be seen in some patients, and there is a higher rate of recurrence.

tips and tricks

tips and tricks

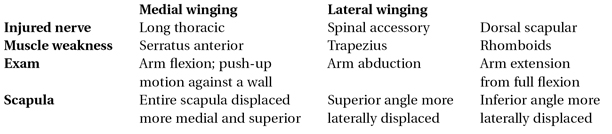

Scapular winging is commonly seen in brachial plexus lesions due to involvement of the long thoracic nerve. However, it also may be seen in trapezius and rhomboid muscle paralysis, and some muscular dystrophies.

Martin RM and Fish DE. Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatment Curr Rev Musculoskel Med 2008;1:1–11 with permission from Humana Press.