Calcification of the Ligamentum Flavum of the Cervical Spine

Sueo Nakama

Yuichi Hoshino

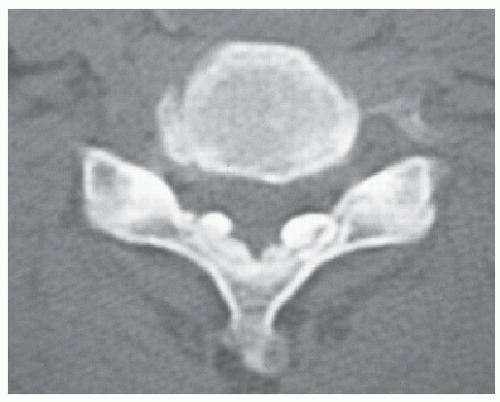

The ligamentum flavum (LF), composed predominantly of yellow elastic fibers, exists in the posterior part of the spinal canal and connects neighboring laminae and articular processes. Calcium crystal deposition rarely occurs in the spinal ligament, and the spinal cord is compressed from the posterior by the characteristic pathologic conditions, such as ossification of the LF (OLF) or calcification of the LF (CLF) (Fig. 65.1).

Radiologically, CLF in the thoracolumbar spine was first described by Polgár (1) in 1929. CLF of the cervical spine was first described in the late 1970s (2). From a review of the literature, the majority of cases with CLF causing myelopathy and/or radiculopathy have been described in Japan, with scattered cases in other countries (3). This fact raises the possibility that this condition has been underrecognized or treated inappropriately outside Japan.

COMPOSED OF CALCIUM PYROPHOSPHATE DIHYDRATE AND THE SPINAL LIGAMENT

From x-ray microanalysis and x-ray diffraction analysis of crystals in patients with CLF, calcified deposits are mainly composed of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) and/or hydroxyapatite (HAP) (4, 5 and 6). The most common calcium-containing crystals in joint disorders are CPPD and HAP, and CPPD deposition often presents as a pseudogout attack. CPPD deposition disease was first recognized as a clinical entity by McCarty et al. (7). Kawano et al. (4) demonstrated the presence of two patterns of crystal deposition in the LF—nodular and linear deposition—and they suggested that the calcification might be induced by CPPD deposits, as seen in cases of pseudogout. They concluded that CPPD crystal deposition disease and so-called calcification of the LF are the same disease and that HAP crystals are transformed from CPPD. Thus, it is widely accepted that CLF results from CPPD crystal deposition. Tumoral calcinosis is a rare condition characterized by the rapid development of large, multilobulated calcific masses in the juxta-articular regions of the extremities in young subjects. Tumoral calcinosis occurs outside the LF as well. However, the relation between tumoral calcinosis and CPPD crystal deposition disease is obscure.

HISTOPATHOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Macroscopically, in nodular deposits, a chalky white substance and a rough granular paste-like consistency is present in the central part of the deposits (Fig. 65.2).

The ultrastructure of the calcified nodules of the cervical LF has been studied. Kubota et al. (8) observed extracellular plasma membrane-invested matrix vesicles and thick wall-bound matrix giant bodies with or without mineralized deposits. They concluded that the mineralization process of the calcified nodules in the LF implies that matrix vesicles and matrix giant bodies acquire mineralized precipitates; subsequently, some gather in clusters. Calcified deposits may spread to collagen and elastic fibers contiguous with the calcified vesicles and bodies, and some eventually coalesce to form a calcified nodule. Hijioka et al. (9) demonstrated that HAP crystal deposition occurs around the growing capillaries on the dural side of the LF, and they concluded that HAP crystal deposition occurs in the healing process of the minor traumatic ligament. Thus, degenerated elastic fibers play an important role in calcium deposition (5).

CLF is relatively common in the middle and lower cervical spine but extremely rare in the upper cervical region. This clinical fact suggests that there exist local factors promoting or preventing LF calcification. However, little is known about the differences in the ultrastructure and cellular alterations of the LF between the different spinal levels, even in the cervical spine. We found direct evidence for the apoptosis of ligament cells in the LF, and apoptosis was more apparent in the upper than in the lower cervical spine (10). The spaces around the normal fibroblasts were filled with thick collagen fibrils, but the collagen fibrils disappeared around the apoptotic bodies and thin fibrils were formed. The difference in the level of apoptosis may correlate with the ultrastructural difference of the LF. Our data will aid further investigations seeking to clarify the mechanism of various pathologic conditions in the human LF.

Alterations in the LF matrix, elastic fiber breakdown, and an increase in the amount of collagen may accelerate the formation of calcified deposits. Repetitive microtrauma (9), hypertrophy of the LF (11), and many other factors have been reported as the pathogenesis of CLF; however, the precise mechanism of calcification is still unknown.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Based on case reports, elderly females appear to exhibit a higher susceptibility to CLF. Characteristic clinical findings in CLF are not always present. The most common presentation is subacute myelopathy due to spinal cord compression. The most prominent presenting symptoms are subjective disorders of sensation in the upper limbs, clumsiness, and difficulty in walking, that is, cervical myelopathy. Neck pain and/or nerve root pain with low-grade fever have been reported and ascribed to a flare of inflammation at the calcified sites (12). Objective neurologic abnormalities include motor loss, sensory loss, and pyramidal tract findings predominantly of the upper limbs. Examination of the spine showed no abnormality in most cases. Laboratory tests have been of little assistance.

IMAGING

CLF is more common in the middle and lower cervical spine and cervicothoracic junction. Although calcified deposits can be seen in plain radiographs (Fig. 65.3), CT examination is the key procedure in making a diagnosis of CLF (Figs. 65.1, 65.4, 65.5 and 65.6). The calcification usually appears as an oval-shaped lesion located in the paramedian area of the posterior part of the spinal canal (Figs. 65.1, 65.4, and 65.5). If OLF occurs in the cervical spine, diagnostic confusion may arise between OLF and CLF. OLF merely extends medially from the capsule of the articular process and shows continuity with the bony laminae (Fig. 65.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree