Introduction

This monograph describes broadly the health services for epilepsy in Canada. A brief overview of the Canadian health care system provides the basis for a portrayal of services covered, challenges to epilepsy care in Canada, and specific epilepsy health care services by province.

A depiction of the Canadian geography is pertinent as this is directly relevant to health care delivery. Canada spans an area of approximately 10 million km2, of which a substantial proportion is north of 60th parallel and in the arctic regions. Approximately 31 million people inhabit ten provinces and three territories, with a population density of 3.1 residents per km2, one of the lowest in the American Continent. The boundaries of the vast Canadian expanse comprise the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans. Two thirds of the population (20 million) live in metropolitan areas, most of which are located in proximity to the southern national border. The large northern areas encompassing the Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavik have only 100,000 inhabitants.7 It is readily apparent that geography poses a gargantuan challenge to equal access to health care services.

The Canadian Health Care System

The Canadian Health Care system rests on the principles enshrined in the Canada Health Act, whose tenets are equity and solidarity. Its objective is to ensure that all eligible Canadian residents have reasonable access to insured health services on a prepaid basis, without direct charges at the point of service. Canada’s National Health Insurance Program consists of 13 interlocking provincial and territorial health insurance plans, all of which share certain common features and basic standards of coverage. The roles and responsibilities for Canada’s health care system are shared between the federal and provincial-territorial governments. The latter are responsible for the management, organization, and delivery of health services for their residents. Essentially, each province or territory has a list of insured services covered by the national insurance program. These comprise the great majority of medically necessary physician and hospital services. There is interprovincial reciprocity of services with the exception of the province of Quebec. Physicians can refer anywhere in Canada if services are not available locally or if they are justified by complexity. There is variable coverage of medication, eye care, dental care, and allied health care services. In general, medications are not covered except in special populations, such as the elderly, disabled or unemployed, and registered natives and Inuits. Each province has a medication list whose contents vary by province. Restricted use is specified if other drugs fail. A special application is required for unlisted drugs. In jurisdictions that have drug coverage, a copayment by the patient is required. This is widely variable, ranging from the prescription cost up to a maximum yearly of $850 CDN, and then a portion of the excess in some provinces. This coverage may take income into account. A few groups have complete coverage without copayment, including children. All consults to specialists require referral by general practitioners or family doctors, and some allied health care services also require referrals.

Access to Health Care

Statistics Canada carries out national surveys that evaluate access to health care.6 In 2003, 20% of the general population reported some difficulty accessing specialized care and 15% had some difficulty accessing diagnostic tests. The main barriers to access were long wait times for service, reported by approximately 60% of those patients who identified any type of difficulty. The health access survey also assessed the effect of waiting for specialized care. The main effect of waiting was worry or stress (60% of individuals), whereas only 20% reported worsening of health status as a result of waiting. Interestingly, people with epilepsy in rural areas report fewer barriers to health care than those in urban areas.9 This somewhat counterintuitive finding may have two possible explanations. Epilepsy care in rural areas occurs mostly through family physicians and emergency rooms, which are more readily accessible than urban specialists with long waiting lists. Alternatively, more complex patients requiring multiple levels of health care, which are often less accessible, may migrate to urban settings. Population surveys in Canada have also shown that patients with epilepsy have a higher use of specialists, nursing, and allied health services than patients with other common chronic conditions.9

According to Statistics Canada and the Canadian Institute of Health Information, the ratio of population per hospital in Canada is approximately 31,000, and there is approximately one hospital per 9,260 km2.2 The latter varies substantially among regions and provinces, from a low of 3,000 km2 per hospital in Ontario to a high of 450,000 km2 per hospital in the northern territories. In general, populated provinces have more and busier hospitals that are often nearly fully occupied, whereas provinces and territories with few inhabitants have fewer hospitals per area, distributed over vast and remote geographic regions, and with more challenging access.

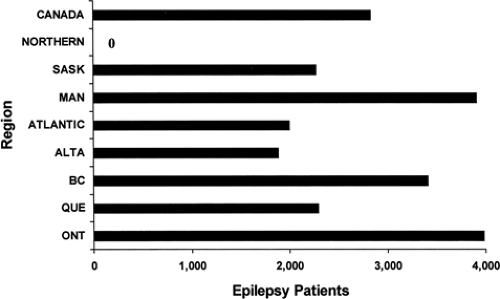

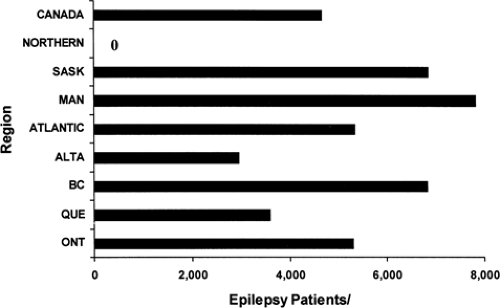

According to a 1996 survey of specialist manpower, the mean distance from a general practitioner to a neurologist was 102 km, and it was 135 km for a neurosurgeon. This is highly variable among regions. In 2002, there were 694 neurologists in Canada, resulting in a ratio of 44,700 people per neurologist. This also is highly variable among regions, ranging from zero neurologists in the three vast northern territories to 218 in Ontario, and resulting in the following population-to-neurologist ratios: British Columbia, 43,000; Alberta, 43,200; Saskatchewan/Manitoba, 74,700; Ontario, 50,100; Quebec, 33,400; and Maritime Provinces, 61,000.1 In most provinces the ratio has decreased over time (e.g., more neurologists per population), with the exception of Saskatchewan and Manitoba, where the number of neurologists has actually decreased over the last few years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree