Fig. 4.1

RCVS in the setting of marijuana use. The patient presented with acute thunderclap headache after smoking cannabis. Coronal MIP MRA (a) performed 24 h after symptom onset demonstrates multifocal areas of posterior circulation cerebral vasoconstriction (arrows). Coronal MIP MRA of the vertebrobasilar system performed 4 months later (b) shows resolution of changes

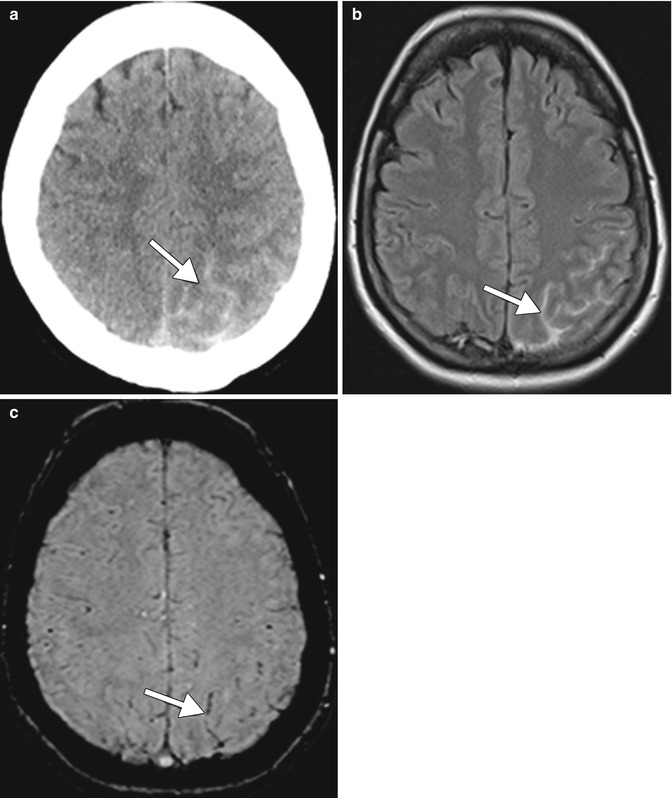

Fig. 4.2

Hemorrhagic stroke due to marijuana. Axial CT on admission (a) with corresponding axial FLAIR MRI (b) and axial susceptibility-weighted image (SWI) (c) reveals left parietal subarachnoid hemorrhage (arrows). The acute subarachnoid hemorrhage is more conspicuous on the FLAIR image than the SWI

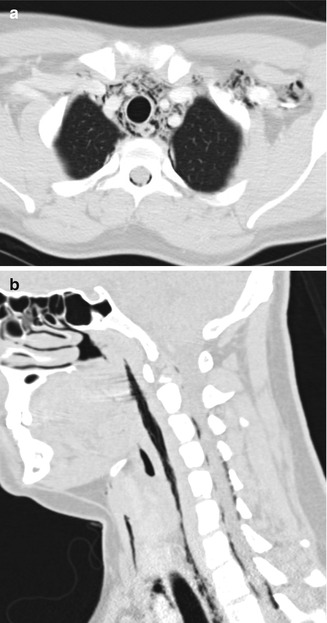

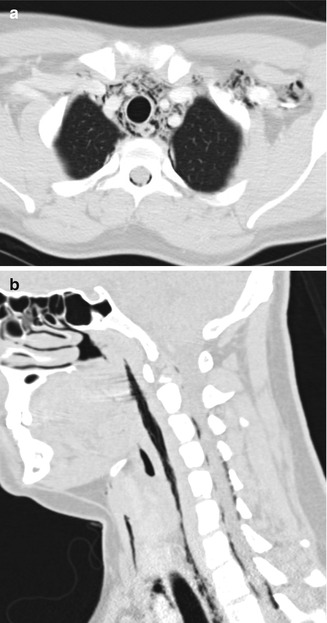

Smoking of marijuana using devices such as a narrow outlet bong can result in barotrauma associated with repeated deep inspiration with airflow resistance that is equivalent to performing Müller’s maneuver. Successive inhalation through high resistance can result in extreme negative intrathoracic pressure, which causes a transmural pressure gradient inducing barotrauma and release of extra-respiratory air. Air can enter multiple compartments, including the epidural space of the spine, deep neck spaces, subcutaneous tissues, and mediastinum, which can be readily depicted on CT (Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3

Barotrauma due to marijuana smoking. Axial (a) and sagittal (b) CT image show extensive air attenuation within the spinal canal, deep spaces of the neck, and upper mediastinum (Courtesy of Alaa Jaly, Chris Coutinho, and Sachin Mathur)

4.4 Differential Diagnosis

An important diagnostic consideration for cannabis-induced RCVS is vasospasm secondary to aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Other differential considerations include other drug-induced cerebral vasculopathy and other causes of reversible vasoconstriction syndrome such as migrainous angiitis and central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis. Differentiation between the various diagnostic possibilities is aided by the clinical presentation, relevant personal history, and patient demographics.

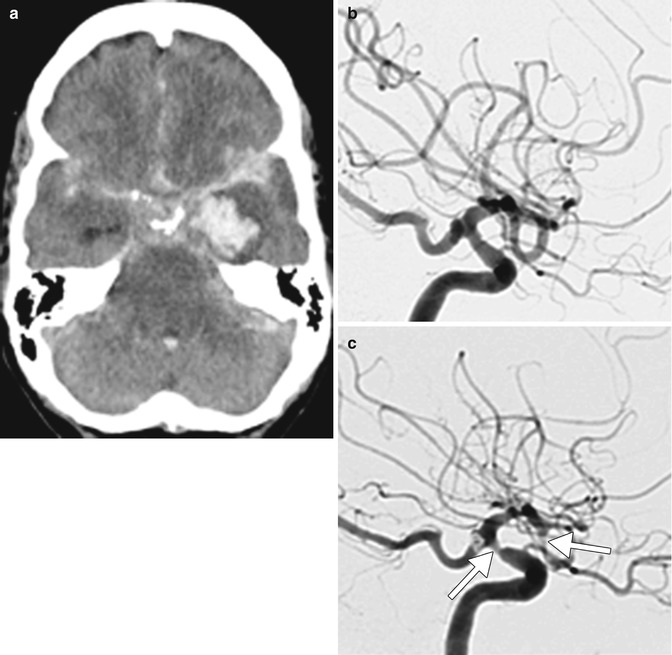

Aneurysmal rupture and secondary vasospasm: A difficult diagnostic dilemma may arise when an intracranial aneurysm is identified on angiography, despite the changes being attributable to RCVS. In this situation, the distribution and extent of subarachnoid blood and the location of cerebral vasospasm is invaluable in ascertaining the diagnosis (Fig. 4.4). In general, cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage is associated with RCVS and basal subarachnoid hemorrhage with aneurysmal rupture. Cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage could be associated with ruptured distal mycotic aneurysm; however, there is usually a history of intravenous drug use or infective endocarditis that predisposes to septic emboli.

Fig. 4.4

Aneurysmal intracranial hemorrhage. Non-contrast axial CT on admission (a) reveals subarachnoid, intraventricular, and left temporal intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Lateral DSA (b) performed on the day of admission reveals the normal large cerebral vascular caliber and 4 mm right posterior communicating artery aneurysm. Lateral DSA (c) performed for neurological deterioration 10 days later shows marked new focal stenoses of the internal carotid artery and proximal middle cerebral arteries (arrows)

Other drug–induced RCVS: A wide range of compounds have been associated with the drug-induced form of RCVS. These include phenylpropanolamine, pseudoephedrine, ergotamine tartrate, methylergonovine, bromocriptine, lisuride, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), sumatriptan, isometheptene, cocaine (refer to Chap. 5), amphetamine derivatives (refer to Chap. 6), lysergic acid diethylamide, tacrolimus (FK-506), cyclophosphamide, erythropoietin, intravenous immune globulin (IVIg), interferon alpha, nicotine patches, red blood cell transfusions, licorice (refer to Chap. 9), and oral contraceptives. The radiological features are identical to other causes of RCVS, and the history is invaluable in identifying the offending agent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree