INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) are neurodegenerative, progressive, chronic illnesses with an unpredictable clinical course. Compounding this tragedy is that caregivers’ mental and physical well-being suffers, and their activities and social relationships are disrupted, leading them to discontinue home care. This chapter highlights the vital caregiver role, and the costs to and support for home caregivers and those in the process of relocating a patient to an institutional setting. We review the positive and negative effects of caregiving, the psychosocial and physiological outcomes, and variables that mediate the stressors inherent in caregiving.

Of the estimated 5.3 million Americans with ADRD, over 80% are cared for by family members and friends, typically spouses1–3. Most families want to forestall or avert institutionalization of those with ADRD, so the aging US population presents a significant societal challenge.

Who are Family Caregivers?

Caregiving typically falls to women, who provide 72% of care: 29% are adult daughters and 43% are wives4. Nonetheless, both men and women caregivers of persons with dementia (PwDs) devote a similar amount of time to caregiving service and, more importantly, perceive similar levels of stress. Most stress arises from dealing with behavioural problems. This stress is a common precipitant of institutionalization5,6.

Public Policy and Cost Implications of Caregiving

Policy makers recognize that families are the mainstay of caregiving and that such care comes at considerable cost (i.e. home modifications, assistive devices, special food, high utility costs and lost wages7–9). Conservative estimates indicate that family caregivers of PwDs saved the US health care system $350 billion in 200610. With the population ageing, this estimate will increase. Although family caregiving greatly relieves costs to society, it concentrates financial burdens onto caregiving families. Moreover, monetary estimates in no way reflect the human costs of this devastating disease. Indeed, caregiving correlates with other adverse consequences, such as poor health11–13.

CAREGIVER STRESS AND BURDEN AND ITS IMPACT ON CAREGIVER WELL-BEING

The concept of caregiver burden is used as an all-encompassing term referring to the financial, social, physical and emotional effects of caregiving. Numerous studies have examined the burden and stress of caring for a PwD, the effects on mental and physical health, and the use of a variety of interventions to relieve caregiving burden.

Family caregivers of persons with ADRD experience stressors that affect their health and well-being, and precipitate institutionalization of the care recipient. Hence, ‘stress’ has emerged as an important concept, with the words ‘stress’, ‘burden’, and ‘distress’ often used interchangeably. Spouses may be at greatest risk, as they are often elderly themselves14. In a common pattern, the distress and depression caregivers experience precipitates physiological changes and poor health habits, leading to illness15.

Models of Caregiver Stress

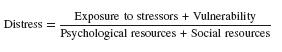

Several theoretical frameworks have guided studies of PwDs, their family caregivers and how interventions affect both16. Stress models, in particular, have guided much of this research, showing that the care recipient’s level of impairment is not a linear predictor of caregiver stress17,18; instead, caregiver stress is moderated by many factors, including the caregiver’s physical health, social support, financial assets, coping abilities and personality. For example, Vitaliano et al.19,20 stratified resources and vulnerability variables of both the caregiver and care recipient, to pinpoint relationships among stressors, resources and burden. Vitaliano considered both psychological and biological markers of distress, and expressed them in a mathematical formula in which the level of caregiver distress (burden) decreases with reduced undesirable variables or increased desirable variables:

Other studies, examining racial differences in caregivers of PwDs, found stress levels to be affected by overarching factors that reflect personal context (e.g. being able to financially provide for their family and getting leisure time away)21.

Stressors Associated with Family Caregiving

The profound cognitive and behavioural changes of ADRD include progressive loss of memory, judgment, the ability to interpret abstraction, and language and motor skills, as well as personality changes. ADRD culminate in an inability to perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as cooking and managing money and, as the disease progresses, more basic activities like bathing and toileting. Researchers disagree on whether the level of a care recipient’s functional or cognitive impairment correlates with caregiver burden22,23. Notably, however, a recent study found caregivers’ quality of life did correlate with the severity of the care recipient’s behavioural disorders and duration of the disease process24.

ADRD has an unpredictable course and pace of decline; the only certainty is that the disease is progressive. As dementia progresses, caregivers must be increasingly vigilant, since a PwD may unexpectedly leave home or injure themselves. In the final stages, patients are often completely dependent on their caregivers, making caring for a PwD eventually an all-consuming job.

Behavioural Impairments in Care Recipients

Most commonly, the reported behavioural changes of ADRD include lethargy, withdrawal, sleep disturbance, restlessness, wandering, aggression, destroying property and verbally disruptive or sexually inappropriate behaviour25–27. The stress of providing 24-hour care mounts when the PwD becomes agitated, stressed or disoriented. Behavioural abnormalities appear in up to 67% of care recipients upon diagnosis28, in 65% of institutionalized persons26, and in 70–90% of persons with advanced dementia29,30. They worsen with disease progression and may be related to fatigue, change, over-stimulation, excessive demands or physical stressors31. Moreover, the care recipient’s behavioural problems are the characteristic that overwhelmingly predicts caregiver distress22,32, making this a strong predictor of institutionalization33.

Other Factors that Influence Caregiver Stress

Caregiving for persons with ADRD entails years of constant demands. Over the disease trajectory, the intensity and/or frequency of a caregiver’s level of distress may vary widely. To understand this variability, investigators try to identify factors associated with differing outcomes. Stress may be influenced by whether the caregiver and recipient reside together, the abruptness of the disease onset, the family relationship, and the caregiver’s coping strategies34,35; also caregiver burden was reportedly more intense for spouses than for adult children32. Positive outcomes, however, are associated with a strong social network and satisfactory support36.

In sum, the relationship between the caregiver’s psychological distress and physical impairment depends on many variables, for instance the care recipient’s behaviours and caregiver vulnerability (e.g. age, gender, neuroticism, pre-existing hypertension, and social support). Nonetheless, the factors contributing to caregiver distress have only recently been delineated well enough to effectively direct interventions or preventative strategies37–40.

Dementia Versus Non-dementia Caregiving

The risk for health problems increases with the physical demands of caregiving, prolonged distress and the biological vulnerability of older caregivers. Research suggests that caring for a PwD is more demanding than caring for physically impaired older adults41. In a review of studies of caregiving in different types of illnesses, Biegel, Sales, and Schulz42 observed different patterns of distress. Distress peaked after the initial diagnosis, but, as time passed, the level of distress fell. This pattern, however, was not observed in family care-givers of persons with a gradual onset, where no relief of distress was observed43.

POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE OUTCOMES OF FAMILY CAREGIVING FOR PERSONS WITH DEMENTIA

It is notable that mounting evidence suggests that some caregivers find satisfaction in the caregiving role and report life satisfaction, emotional uplifts, enhanced self-esteem and self-efficacy, optimism, and growth and meaning44–49. Interviews of 50 caregivers of PwDs found 58% experienced ‘self-fulfilling’ experiences during caregiving, with the same percentage expressing ‘losses and difficulties’50. Positive aspects of caregiving were related to the caregiver’s competence. Brown and colleagues51 found that caregivers who provided instrumental support to friends, relatives or neighbours, or who provided emotional support to their spouses, had lower five-year mortality rates.

IMPACT OF CAREGIVING ON HEALTH OF CAREGIVERS

Despite some inconsistent findings concerning how caring for PwDs affects mental and physical health, most but not all studies find increased psychiatric and physical morbidity52–55. This suggests that inconsistencies are attributed to differences in caregivers’ coping strategies.

Mental Health Outcomes

Caring for an older person with ADRD puts one at risk for extreme psychological distress. A number of studies link stress to factors such as the strain of providing direct care, grief from witnessing the decline of their loved ones, social isolation and role changes. These effects occur with home care, following institutionalization, and during bereavement37,56.

Depression

Depressive symptoms are among the mental health changes most frequently reported by family caregivers of PwDs. A complex interaction of cultural factors57,58, caregiver and receiver characteristics come into play, predicting depression59–61. Moreover, depression among caregivers is associated with the intensity of their reactions to the patients’ memory and behaviour problems62 and to other outcomes such as increased physical and subjective burden63,64, and the use of psychotropic medications22,65.

Predictors of caregiver depression include a younger age of care-giver and care receiver, Caucasian race, Hispanic ethnicity compared to black ethnicity, higher education, activities of daily living dependence, and the recipient’s behavioural abnormalities (particularly aggressive or angry behaviour). Other predictors include low income, spousal status, hours spent caregiving and functional dependence of the caregiver61,66. Depression is greater among females than males6 and appears to increase over time among residential caregivers and decrease over time following institutionalization and bereavement67. Compared to non-caregiving men, male spouse care-givers have higher levels of depression, respiratory symptoms, and poorer health habits, although the groups did not differ on other measures of physical and mental health68.

Anxiety

Several investigators incorporated self-reported measures of anxiety when examining depression among caregivers. Some found that caregivers who presented with symptoms of depression also often reported symptoms of anxiety18,69. Overall, strong evidence suggests caregivers are at risk for psychiatric symptomatology. Yet, caution must be exercised when interpreting the generalizability of these findings, since many samples may be biased towards more distressed caregivers. For example, most caregivers are recruited from chapters of the Alzheimer’s Association, support groups, or through referrals by health professionals; either individuals who have little difficulty with the caregiving role or are so distressed or constrained that they cannot participate in supportive programmes or visit health care professionals, may be under-represented. Additionally, transient psychiatric symptoms may be more common than diagnosable depression. Moreover, caregiver burden does not always predict depressive symptoms, suggesting that the relationship between caregiver burden and caregiver depression is complex66.

Physical Health Outcomes

Most studies examining the physical effects of caregiving used one or more indicators of caregiver health: (i) self-reported health status; (ii) self-reported incidence of illness-related symptoms; (iii) self-reported utilization of health care services; (iv) self-reported medication use; and (v) disease susceptibility. Predictors of poor physical health outcomes for caregivers include being older, a spouse and female22,70. Interestingly, however, in some cases caregiving was also reported to improve physical health. Family caregivers with coronary heart disease (CHD), who experienced emotional uplifts, also showed less severe metabolic signs that predict CHD20,71.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree