Fig. 10.1

RCVS associated with Centella asiatica. Fifty-eight-year-old female presenting 10 days after initial acute thunderclap headache. Symptoms began 48 h after ingestion of a large quantity of Centella asiatica. Neurological deterioration 5 days after DSA prompted MRI (a, b), which shows T2 hyperintensity and restricted diffusion in the splenium of the corpus callosum, consistent with infarction (arrows). MIP time-of-flight MRA (c) performed in the third week after initial ingestion demonstrates extensive multifocal areas of cerebral vasoconstriction (arrowheads). MIP time-of-flight MRA performed 6 weeks after initial ingestion (d) shows resolution of the abnormalities

Treatment involves identification and withdrawal of the vasoactive stimulus, supportive care, and management of ischemic and hemorrhagic complications.

10.4 Differential Diagnosis

An important diagnostic consideration is vasospasm secondary to aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Other differential considerations include central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis, postpartum cerebral angiopathy (PPA), and other causes of reversible vasoconstriction syndrome, such as migrainous angiitis and other drug-induced cerebral vasculopathies. Differentiation between the various diagnostic possibilities is aided by the clinical presentation, relevant personal history, and patient demographics.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Aneurysmal rupture and secondary vasospasm: A difficult diagnostic dilemma may arise when an intracranial aneurysm is identified on angiography, despite the changes being attributable to RCVS. In this situation, the distribution and extent of subarachnoid hemorrhage and the location of cerebral vasospasm are invaluable in ascertaining the diagnosis. In general, subarachnoid hemorrhage is associated with RCVS and basal subarachnoid hemorrhage with aneurysmal rupture. Subarachnoid hemorrhage could be associated with ruptured distal mycotic aneurysm; however, there is usually a history of intravenous drug use or infective endocarditis that predisposes to septic emboli.

CNS vasculitis: This may be primary in etiology, in which the arteritis is confined to the CNS vessels, or secondary, where there is a history of systemic vasculitis, most often systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the latter situation, CNS involvement is unlikely to be the first manifestation of the disease, as there is almost always a history of systemic vasculitis. While the radiological features of primary CNS vasculitis can overlap with RCVS, the clinical onset of CNS vasculitis is more insidious, the headache is chronic and progressive, and there are usually accompanying cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities. Multiple ischemic lesions can be encountered on MRI (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3).

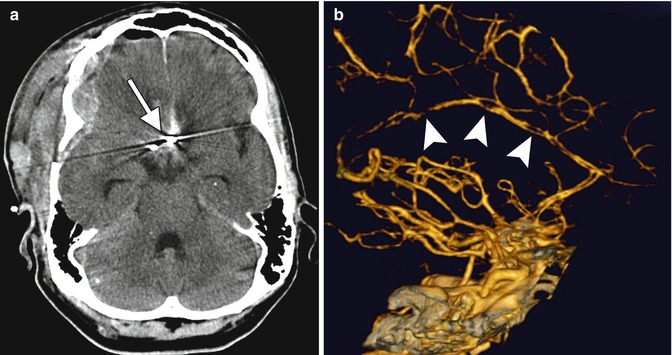

Fig. 10.2

Vasospasm associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Axial CT image (a) shows anterior communicating artery aneurysm clipping and associated hemorrhage from recent rupture (arrow). Lateral 3D CTA (b) shows multiple high-grade stenoses of the anterior cerebral arteries (arrowheads)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree