Chiari Malformations

16.1 History and Classification

In the early 1890s, Dr. Hans Chiari1 used autopsy specimens to describe four congenital anomalies, later termed the Chiari malformations (▶ Table 16.1). The four traditional varieties of Chiari malformation represent varying degrees of involvement of rhombencephalic derivatives. Three of these (types 1 through 3) have progressively more severe herniation of these structures outside the posterior fossa as their common feature. These three types also have in common a pathogenesis that involves a loss of the free movement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) out of the normal outlet channels of the fourth ventricle. Pathologic differences between Chiari 1 malformations (C1Ms) and Chiari 2 malformations (C2Ms) can be explained with knowledge of the differences in the timing of the development of the vector of force across the foramen magnum.

| Type | Characterized by: |

| Chiari type 1 | Tonsillar herniation > 5 mm inferior to the McRae line No associated brainstem herniation or supratentorial anomalies Hydrocephalus uncommon Syringomyelia common |

| Chiari type 2 | Herniation of the cerebellar vermis, brainstem, and fourth ventricle through the foramen magnum Almost always associated with myelomeningocele and multiple brain anomalies(see box “Findings Associated with Chiari 2 Malformations”)Hydrocephalus and syringomyelia very common |

| Chiari type 3 | Foramen magnum encephalocele containing herniated cerebellar and brain stem tissue |

| Chiari type 4 | Hypoplasia or aplasia of the cerebellum and tentorium cerebelli |

Although a large majority of cases are congenital, acquired C1Ms occur and are not rare. Not considered further in this chapter are the patients who have movement of their cerebellar tonsils into the cervical spine because of an intracranial tumor or other mass, especially within the posterior fossa. Technically, these patients have a C1M, but treatment of the cause of their hindbrain hernia usually allows resolution of their secondary C1M.

Several subclassifications have been developed for patients with hindbrain hernias, which are due to some problem with equilibrating CSF across the craniocervical junction. These classifications are as follows.

16.1.1 Chiari 0

Patients who do not appear to have significant hindbrain hernias, even though the posterior fossa may appear “crowded,” and who have large syringes that resolve with posterior fossa decompression are classified as having Chiari 0 malformation.2 Their condition indicates that they have a fourth ventricular outlet obstruction, and at surgery they frequently do have physical barriers to CSF movement but do not have caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils beyond a point that could be considered pathologic (< 5 mm). These patients are included in the current chapter because their presentation and surgical intervention are the same as those of patients with frank hindbrain herniation.

16.1.2 Chiari 1

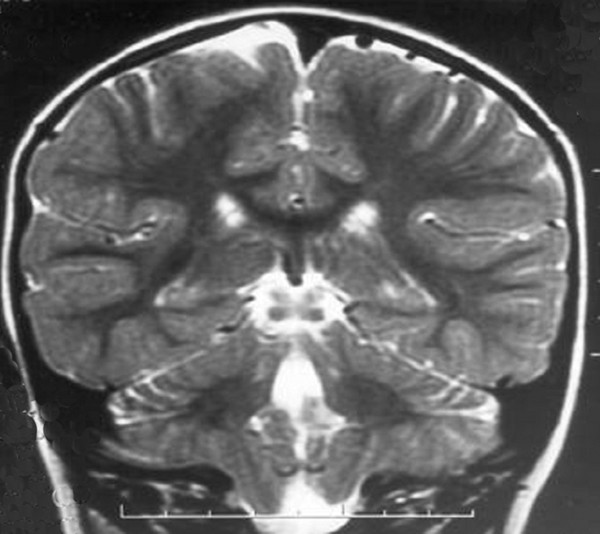

Patients in this common group have caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils more than 5 mm below the foramen magnum (▶ Fig. 16.1). The brainstem is in a normal position. They may or may not have a syrinx. The 5-mm “rule” concerning the definition of the pathologic extent of the caudal migration of the tonsils is arbitrary. Numerous patients have tonsils well below this point and are asymptomatic, especially young infants and children. When followed over time, they frequently remain asymptomatic if their initial evaluation was performed for an unrelated reason. The extent of their caudal migration may progressively decrease with time and become less impressive. This, however, is not certain, and the patient should be followed for the development of symptoms. A host of conditions are associated with the C1M. Many are listed in the box “▶ Reported Associations with Chiari 1 Malformations.”

Fig. 16.1 Coronal magnetic resonance image demonstrating a Chiari 1 malformation. Note the asymmetry of the descended cerebellar tonsils.

Reported Associations with Chiari 1 Malformations

Klippel-Feil anomaly

Odontoid retroflexion

Growth hormone deficiency

Neurofibromatosis

Pierre Robin syndrome

Costello syndrome

Caudal regression syndrome

Hemihypertrophy

Lipomyelomeningocele

Crouzon syndrome

Apert syndrome

Multisutural craniosynostosis

Paget disease

Craniometaphyseal dysplasia

Rickets

Acromegaly

16.1.3 Chiari 1.5

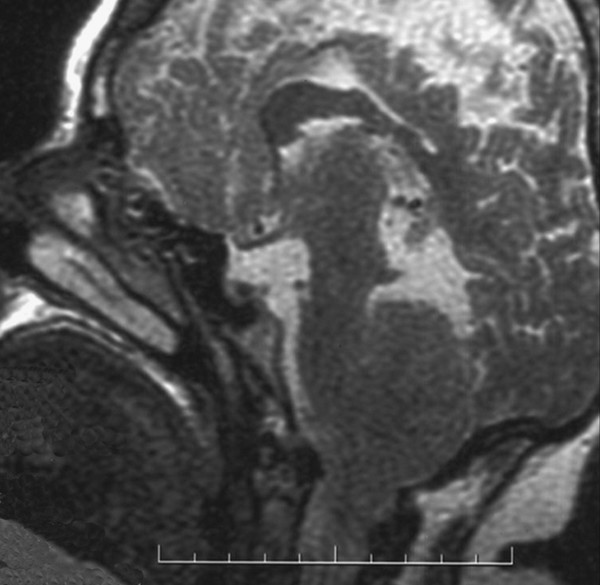

Although somewhat confusing, this term is applied to patients who bridge the gap between C1M and C2M. They have characteristics of both groups and are best considered separately. Their malformations are unassociated with neural tube defects, and caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils is similar to that in patients with C1M. However, their brainstem and fourth ventricle are low, like those in patients with C2M (▶ Fig. 16.2). In our series of patients without a neural tube defect and a hindbrain hernia, 17% had significant caudal displacement of the brainstem.3 Based on our series, these patients appear to have a greater chance of developing syringomyelia.

Fig. 16.2 Sagittal magnetic resonance image illustrating tonsillar ectopia and caudal descent of the brainstem (i.e., the Chiari 1.5 malformation). Note the extensive syringomyelia with a skip region at C1–C2.

16.1.4 Chiari 2

This lesion occurs in patients with neural tube defects (myelomeningoceles and encephaloceles). It consists of caudal migration of the cerebellar vermis rather than of the cerebellar tonsils, brainstem, and fourth ventricle (▶ Fig. 16.3). Syringomyelia is common, as are a host of additional findings (see box “▶ Findings Associated with Chiari 2 Malformations”).

Fig. 16.3 Vermian herniation in the Chiari 2 malformation as demonstrated on a sagittal magnetic resonance image.

Findings Associated with Chiari 2 Malformations

Skull

Craniolacunia

Scalloping of the petrous bones

Foreshortening of the internal acoustic meatus

Enlarged foramen magnum

Small posterior fossa

Notching of the opisthion

Scalloping of the frontal bone (lemon sign)

Cranioschisis

Clival concavity

Inferiorly displaced inion

Midline occipital keel

Assimilation of the atlas

Spine

Enlarged cervical canal

Scalloping of the odontoid process

Incomplete posterior arch of C1

Klippel-Feil deformity

Basilar invagination

Ventricle/cistern

Hydrocephalus

Asymmetry of the lateral ventricles

Lateral pointing of the frontal horns

Colpocephaly

Shark tooth deformity of the third ventricle

Commissure of Meynert

Small fourth ventricle that is flat and elongated

Extraventricular location of the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle

Absence of the inferior medullary velum

Absence or cyst of the foramen of Magendie

Enlarged cerebellar and pontine cisterns

Meninges

Widened, heart-shaped, low-lying, hypoplastic, venous lake–engorged tentorium cerebelli

Vertical straight sinus

Confluence of sinuses near opisthion

Falx cerebri/cerebelli hypoplasia/aplasia

Thickening of the leptomeninges at the foramen magnum

Arachnoid cysts of the cervical canal

Thickening of the cephalic dentate ligaments

Spinal cord

Split-cord malformation

Syringomyelia

Exophytic syringes

Shortened and caudally displaced cervical spinal cord

Reduced neuronal counts in the cervical cord

Reduction in myelinization of the corticospinal tracts

Telencephalon

Complete or partial agenesis of the corpus callosum and/or septum pellucidum

Polygyria

Chinese lettering (interdigitation of the parieto-occipital lobes)

Agenesis of the olfactory tract and bulb

Agenesis of the cingulate gyrus

Prominence of the head of the caudate nucleus

Heterotopias

Diencephalon

Enlarged massa intermedia

Anterior displacement of the massa intermedia

Elevation of the hypothalamus

Elongation of the habenular commissure and pineal gland

Mesencephalon

Elongation of the midbrain with a shortened tectum

Tectal beaking (fusion of the superior and inferior colliculi)

Stenotic, stretched, forked, or kinked cerebral aqueduct

Metencephalon

Small cerebellum that may tower superior to the tentorium cerebelli

Vermian herniation through the foramen magnum

Cranial nerves that traverse the cerebellar folia and that may be dysplastic

Curvature (inversion) of the cerebellum with resultant “kissing” of the left and right sides (banana sign) anterior to the brainstem

Cerebellar heterotopias

Dysplastic deep gray matter

Elongation of the pons with indentation of its ventral surface

Caudal displacement of the basivertebral arteries

Dysplastic pontine basal nuclei

Dysplastic tegmental and cranial nerve nuclei of the pons

Myelencephalon

Elongation and flattening of the medulla producing a “trumpet-like” structure

Protuberance (medullary kink, hump, spur, buckle) caudal to the gracile and cuneate tubercles

Cephalically located pyramidal decussation

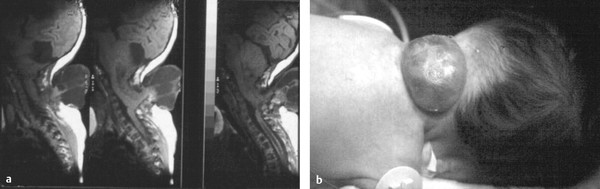

16.1.5 Chiari 3

The Chiari 3 malformation is a rare and extreme form of hindbrain hernia. It is found in fewer than 1% of all patients in this category. Patients have a high cervical sac containing significant portions of the cerebellum and/or brainstem. There are frequently other associated anomalies, similar to those in patients with C2M (▶ Fig. 16.4). Hydrocephalus is common, and severe neurologic and developmental problems are usually present. Treatment consists of ensuring that skin covers the lesions and that tethering is not an issue. This malformation will not be considered further because of its rarity and the limited role that neurosurgery plays in its care.

Fig. 16.4 (a) Sagittal magnetic resonance images and clinical image of a type 3 Chiari malformation, (b) with hindbrain herniation through an upper cervical spina bifida.

16.1.6 Chiari 4

Patients with type 4 Chiari malformation have cerebellar hypoplasia or aplasia. This is not a form of hindbrain hernia. Therefore, inclusion in a discussion of hindbrain hernias is questionable, and this malformation will not be considered further.

16.2 Signs and Symptoms

16.2.1 Chiari 1 Malformations

Patients with a C1M may present with a variety of symptoms and signs ranging from headache to severe myelopathy and brainstem compromise (see box “▶ Clinical Presentation of a Chiari 1 Malformation”). The most common presenting symptom is pain (60 to 70%),4 usually occipital or upper cervical in location and often induced or exacerbated by Valsalva maneuvers such as coughing, laughing, and sneezing. In infants and children who are unable to communicate verbally, headaches may be manifested simply by irritability or grabbing at the neck.5 As many as half of the patients with a Valsalva-induced headache will be found to have a C1M as the cause. If the headache is not Valsalva-induced and if the pain is farther away from the craniocervical junction, it is less likely that a hindbrain hernia is the cause. Adolescents who have a symptom complex with vague frontal or vertex headaches, no syrinx, a normal neurologic examination, and a descent of the tonsils of 5 mm or more is very unlikely to improve symptomatically if a Chiari decompression is performed. This should be contrasted with the 6-month-old child who cries and then reaches for the posterior cervical region, grimaces, and arches the spine. In this case, the original neck pain is relieved postoperatively.

Clinical Presentation of a Chiari 1 Malformation

Symptoms

Occipitocervical headaches/dysesthesia

Nonradicular pain in the back, shoulders, and limbs

Motor and sensory symptoms

Clumsiness

Dysphagia

Dysarthria

Cerebellar syndrome

Truncal and appendicular ataxia

Brainstem syndrome

Respiratory irregularities

Nystagmus

Lower cranial nerve dysfunction, including otologic disturbances

Recurrent aspiration

Hypertension (rare)

Glossal atrophy

Facial sensory loss

Trigeminal or glossopharyngeal neuralgia

Spinal cord syndrome

Motor and sensory losses, especially in the hands

Hyporeflexia

Hyperreflexia

Babinski response

Other signs

Oscillopsia

Esotropia

Sinus bradycardia

Progressive scoliosis

Hoarseness

Hiccups

Urinary incontinence

Drop attacks

Scoliosis

Another major symptom complex includes scoliosis. Scoliosis associated with syringomyelia may sometimes be differentiated from idiopathic scoliosis by a left thoracic curve, abnormal abdominal reflexes, or diffuse nondermatomal pain in the flank or back. Any neurologic abnormality, uncharacteristic pain, or other worrisome change in a patient with scoliosis should alert the clinician to the possibility of a syrinx caused by a C1M.

Other unique symptom complexes may be grouped according to the anatomical area affected: brainstem and cranial nerves, spinal cord, and cerebellum.

Symptom complexes that localize to the brainstem include tongue atrophy, downbeat nystagmus (indicative of medullary dysfunction), and extraocular muscle changes (even an isolated sixth nerve palsy or paresis). Lower cranial nerve dysfunction may occur in 15 to 25% of patients, with gagging, sleep apnea, and difficulty swallowing.6–8 Oropharyngeal dysfunction is common and can manifest as poor feeding, failure to thrive, recurrent aspiration pneumonia, and dysphagia.9 Vocal cord paralysis with stridor or hoarseness is rarely present and is similar to the symptoms of patients with C2M.

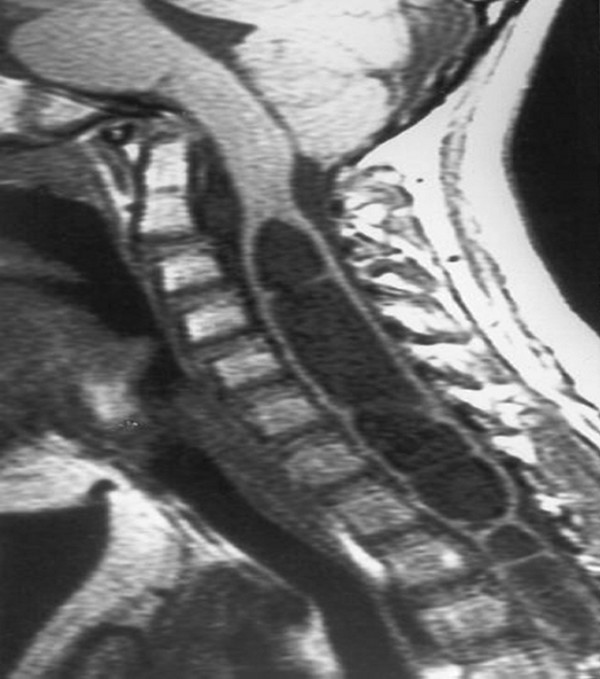

Spinal cord dysfunction is the result of direct cord compression or a syrinx (▶ Fig. 16.5, ▶ Fig. 16.6, and ▶ Fig. 16.7). Older adolescents may describe the classic suspended, dissociated sensory loss, but this will rarely be a spontaneous complaint. The loss of pain and temperature sensation with preservation of light touch and proprioception, when present, will appear over the trunk or hands. This occurs as the crossing fibers are damaged by the progressive enlargement of the intramedullary process. The mechanism of causation of scoliosis is not fully understood. It can be argued that the asymmetric weakness of the paravertebral musculature causes a postural imbalance that manifests as scoliosis.

Fig. 16.5 Sagittal magnetic resonance image of a patient with Chiari 1 malformation and a huge syringomyelia. Note the septa (haustra) within the syrinx.

Fig. 16.6 T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance image of a patient with Chiari 1 malformation. Note the tonsillar level of C2 and the small cervical syrinx.

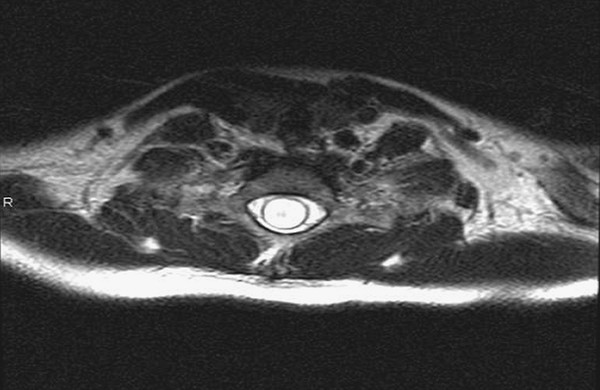

Fig. 16.7 Axial magnetic resonance image through the cervical portion of a holocord syrinx in a young girl. Note the extremely thin nature of the spinal cord. This patient surprisingly had very little symptomatology and presented with scoliosis.

Interestingly, cerebellar dysfunction as a presentation is rare. Cerebellar signs, other than nystagmus, are also rare. There is no apparent neurologic localization for the cerebellar tonsils, despite the presence of gliosis and ischemia commonly seen at operation.

16.2.2 Chiari 2 Malformations

Symptoms of C2M occur characteristically within age groups. As many as one-third of neonates and infants with myelomeningocele may present with serious life-threatening apnea, inspiratory stridor, dysphagia, and bradycardia. The apnea is frequently associated with breath-holding spells. The dysphagia may be so severe that there is a failure to thrive. When these symptoms are present at birth, the situation is grave and implies hypoplasia or aplasia of the appropriate medullary nuclei. If present at birth, the symptoms are generally not reversible. It is more common that medullary symptoms begin within the first few months of life. They may be associated with opisthotonos. When these symptoms develop, normalization of the intracranial pressure with shunt insertion or revision is necessary for active support of the infant.

With regard to the inspiratory wheezing so characteristic of this situation, the “crowing” sound tends to fluctuate with time, increasing with anxiety and diminishing with sleep. When the sound is present while the patient is at rest, the situation is critical and warrants urgent attention.

Older children most commonly display symptoms and signs of spinal cord compromise, with lower motor neuron problems in the arms and upper motor signs and symptoms in the legs. Hyperreflexia in the legs of a patient with myelomeningocele generally requires investigation.

As in patients with C1M, cerebellar signs (other then nystagmus) are uncommon and very rarely a reason for clinical presentation. The box “▶ Clinical Presentation of the Chiari 2 Malformation” summarizes the clinical presentation of patients with C2M.

Clinical Presentation of the Chiari 2 Malformation

Newborns

Usually asymptomatic

Infants

Signs of brainstem compression

Stridor secondary to vocal cord paralysis

Central and obstructive apnea

Aspiration secondary to dysphagia with potential pneumonia

Failure to thrive secondary to dysphagia

Breath-holding spells with possible loss of consciousness

Hypotonia and quadriparesis

Irritability

Opisthotonos

Older children and young adults

Spinal, cerebellar, and ophthalmologic signs

Occipitocervical pain

Hand weakness and loss of muscle bulk

Myelopathy

Ataxia

Strabismus

Nystagmus

Defects of pursuit movements and convergence

Defects of optokinetic movements

Scoliosis

Dysarthria

Neurologic emergency

Usually younger than 2 years, commonly by 3 months of age

Progressive neck pain

Apnea

Dysphagia

Stridor

Opisthotonos

Nystagmus

Progressive brainstem dysfunction

16.3 Diagnostic Studies

16.3.1 Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Chiari 1 Malformations

C1M consists of significant herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. Reasonable criteria for this diagnosis include herniation of one or both tonsils at least 5 mm below the foramen magnum accompanied by other C1M features, such as syringomyelia.10 The tonsillar tip may be pointed, carrying further pathologic significance, or be blunt and rounded, causing less concern. The foramen magnum will appear crowded, with a lack of CSF surrounding the tonsils on T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. In addition, accurate diagnostic guidelines should include the absence of an intracranial mass lesion or hydrocephalus. The liberal use of MR imaging over the last 20 years has greatly facilitated the diagnosis of C1M and increased its apparent incidence. The true incidence of C1M is not known. However, in 7,400 brain dissections, Friede11 found 2 cases plus 46 additional examples of “chronic tonsillar herniation,” which may include many patients who are now classified as having a C1M.

In an early review of 800 MR imaging examinations, one study12 noted that “normal” or “asymptomatic” patients might have tonsils that extend 3 mm below the foramen magnum. The tonsillar herniation was much more likely to be pathologic when it exceeded 5 mm. Similarly, Barkovich et al13 studied 200 normal patients and 25 patients with a “firm” diagnosis of C1M. A distance of 2 mm below the foramen magnum was considered the lowest extent of the tonsils in normal patients (specificity of 98.5%, including three false-positive results, and sensitivity of 100%). A distance of 3 mm below the foramen magnum was considered the lowest extent in normal patients (sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 99.5%). An additional study has documented ascent of the tonsils with increasing age.14

From these studies, it is clear that the practicing pediatric neurosurgeon will see frequent exceptions to the measurements listed above. These studies are useful in screening patients, but the symptom complexes must be analyzed together with the radiologic findings. Patients imaged early in life for unrelated reasons and asymptomatic for Chiari symptomatology may have very impressive MR images. Observing numerous patients in this category who are without symptoms or a syrinx has led us to advocate a conservative approach to intervention. However, operative intervention should be considered for patients with a large syrinx and unimpressive hindbrain herniation and no other cause for the syrinx.

Other associated radiologic anomalies occur infrequently; they most commonly include atlanto-occipital assimilation, basilar invagination, and fused cervical vertebrae. These findings are important to know before surgical positioning.

The combination of hydrocephalus and a C1M is a special subject and is covered later in this chapter. It must be excluded before a family is advised on a course of action.

Chiari 2 Malformations

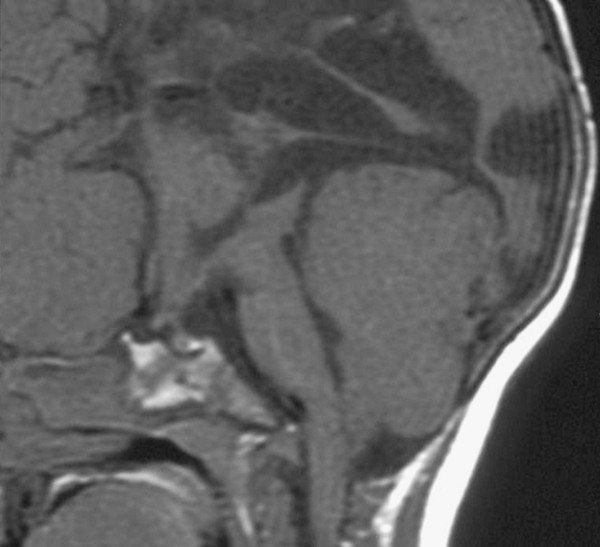

Patients with a C2M are characterized by (1) elongation and caudal displacement of the cerebellar vermis and brainstem structures, (2) the presence of a myelomeningocele or encephalocele in virtually all cases, and (3) hydrocephalus in the majority of cases. Syringomyelia is also commonly seen in this situation (40 to 95%), especially in the lower cervical cord. Other anomalies associated with C2M (see box “▶ Findings Associated with Chiari 2 Malformations”) comprise a set of cranial and spinal malformations. None of these findings is in itself pathognomonic for a hindbrain hernia, but their coexistence is suggestive of a C2M (▶ Fig. 16.8 and ▶ Fig. 16.9). Studies that might be performed in addition to computed tomography (CT) and MR imaging include sleep studies to evaluate for sleep apnea, swallowing studies to demonstrate cricopharyngeal achalasia, and laryngoscopy to verify movement of the vocal cords.

Fig. 16.8 Magnetic resonance image of a Chiari 2 malformation. Note the dysplasia of the corpus callosum, large massa intermedia, flattened pons and medulla, vermian herniation and upward herniation of the cerebellum, tectal beaking, and caudal descent of the confluence of the sinuses.