6 CHOREA Figure 6.1 – In the treatment of chorea, nondrug interventions should be considered first as patients are often not bothered by mild chorea and exhibit no functional impairment related to choreiform movements. – Pharmacologic treatment for chorea may worsen other aspects of movement, cognition, or mood. – Chorea may diminish over time, so that the need for treatment is reduced. – Ask about substance abuse. – Always ask about suicidality, particularly given that impulsivity is common. – Always disclose the results of genetic testing in person and with a relative, caregiver, or friend of the patient present. – Prenatal testing (as early as 8–10 weeks) is possible. – Nonpharmacologic approaches are important in addressing functional difficulties and behavioral dysfunction in HD (Table 6.1). Table 6.1 Problem Solution Dysphagia The patient should eat slowly and without distractions. Foods should be of appropriate size and texture. Eating may need to be supervised. All caregivers should know the Heimlich maneuver. Communication Allow the patient enough time to answer questions. Offer cues and prompts to get the patient started. Break down tasks or instructions into small steps. Use visual cues to demonstrate what you are saying. Alphabet boards, yes–no cards, and other devices can be used for patients in more advanced stages. Executive dysfunction Rely on routines. Make lists that help organize tasks. Prompt each activity with external cues. Offer limited choices instead of open-ended questions. Use short sentences with one or two pieces of information. Impulsivity A predictable daily schedule can reduce confusion, fear, and outbursts. It is possible that a behavior is a response to something else that needs your attention (eg, pain). Let the patient know that yelling is not the best way to get your attention. Hurtful and embarrassing statements are generally not intentional. Be sensitive to the patient’s efforts to apologize or show remorse afterward. Do not badger the person after the fact. Try to keep the environment as calm as possible. Speak in a low, soft voice. Keep your hand gestures quiet. Avoid confrontations. Redirect the patient away from the source of anger. Respond diplomatically, acknowledging the patient’s irritability as a symptom of frustration. Source: Adapted from Ref. 3: Rosenblatt A, Ranen NG, Nance MA, Paulsen JS. A Physician’s Guide to the Management of Huntington’s Disease. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Huntington’s Disease Society of America; 1999.

DEFINITIONS

Phenomenology: chorea, athetosis, and ballism generally represent a continuum of involuntary, hyperkinetic movement disorders.

Phenomenology: chorea, athetosis, and ballism generally represent a continuum of involuntary, hyperkinetic movement disorders.

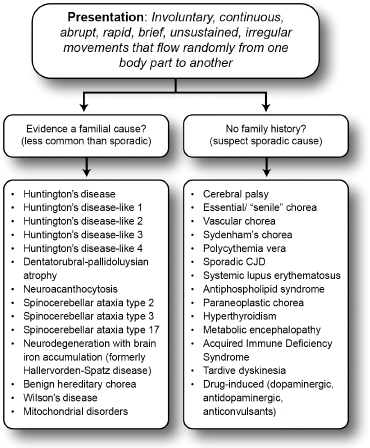

Chorea consists of involuntary, continuous, abrupt, rapid, brief, unsustained, irregular movements that flow randomly from one body part to another.

Chorea consists of involuntary, continuous, abrupt, rapid, brief, unsustained, irregular movements that flow randomly from one body part to another.

Ballism is a form of chorea characterized by forceful, flinging, high-amplitude, coarse movements; ballism and chorea are often interrelated and may occur in the same patient.

Ballism is a form of chorea characterized by forceful, flinging, high-amplitude, coarse movements; ballism and chorea are often interrelated and may occur in the same patient.

Athetosis is a slow form of chorea and consists of writhing movements resembling dystonia. However, unlike in dystonia, the movements are not sustained, patterned, or painful.

Athetosis is a slow form of chorea and consists of writhing movements resembling dystonia. However, unlike in dystonia, the movements are not sustained, patterned, or painful.

Other related disorders that can be confused with chorea, athetosis, or ballism are the following:

Other related disorders that can be confused with chorea, athetosis, or ballism are the following:

Akathisia: a feeling of inner restlessness and anxiety associated with an inability to sit or stand still.

Akathisia: a feeling of inner restlessness and anxiety associated with an inability to sit or stand still.

Restless legs syndrome: a symptom complex of discomfort or unusual sensation in the legs (or arms) that is characteristically relieved by movement of the affected limb(s).

Restless legs syndrome: a symptom complex of discomfort or unusual sensation in the legs (or arms) that is characteristically relieved by movement of the affected limb(s).

CHOREA

Clinical features

Clinical features

Patients can partially/temporarily volitionally suppress chorea.

Patients can partially/temporarily volitionally suppress chorea.

Parakinesia is the act of “camouflaging” some of the choreiform movements by incorporating them into semipurposeful activities.

Parakinesia is the act of “camouflaging” some of the choreiform movements by incorporating them into semipurposeful activities.

The examiner must differentiate chorea from pseudochoreoathetosis (chorea or athetosis secondary to a defect of proprioception).

The examiner must differentiate chorea from pseudochoreoathetosis (chorea or athetosis secondary to a defect of proprioception).

Chorea may be a manifestation of a primary neurologic disorder (eg, Huntington’s disease) or may be secondary to a systemic, toxic, or metabolic disorder.

Chorea may be a manifestation of a primary neurologic disorder (eg, Huntington’s disease) or may be secondary to a systemic, toxic, or metabolic disorder.

Differential diagnosis: see Figure 6.11

Differential diagnosis: see Figure 6.11

Inherited forms of chorea

Inherited forms of chorea

Differential diagnosis of chorea.

Most people develop HD between 30 and 54 years of age, but HD can manifest in individuals as young as 4 years or as old as 80 years of age.

Most people develop HD between 30 and 54 years of age, but HD can manifest in individuals as young as 4 years or as old as 80 years of age.

CAG repeats: normal, 10 to 35; indeterminate, 36 to 39; definite, 40 or more.

CAG repeats: normal, 10 to 35; indeterminate, 36 to 39; definite, 40 or more.

There is a triad of motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms.

There is a triad of motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms.

Motor symptoms: impairment related to involuntary (chorea) and voluntary movements, reduced manual dexterity, dysarthria, dysphagia, gait instability, and falls are common; parkinsonism and dystonia can be seen in patients with an earlier onset of disease.

Motor symptoms: impairment related to involuntary (chorea) and voluntary movements, reduced manual dexterity, dysarthria, dysphagia, gait instability, and falls are common; parkinsonism and dystonia can be seen in patients with an earlier onset of disease.

Cognitive symptoms: initially characterized by loss of speed and flexibility of thinking (executive dysfunction); later, dysfunction becomes more global.

Cognitive symptoms: initially characterized by loss of speed and flexibility of thinking (executive dysfunction); later, dysfunction becomes more global.

Psychiatric symptoms: depression (most common), irritability, agitation, impulsivity, mania, obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety, apathy, and social withdrawal can all emerge in the same patient.

Psychiatric symptoms: depression (most common), irritability, agitation, impulsivity, mania, obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety, apathy, and social withdrawal can all emerge in the same patient.

Diagnosis: based on the clinical presentation, family history, and genetic testing (genetic counseling required for asymptomatic individuals with a family history before genetic testing).

Diagnosis: based on the clinical presentation, family history, and genetic testing (genetic counseling required for asymptomatic individuals with a family history before genetic testing).

Huntington-like syndromes (Table 6.2)3–10

Huntington-like syndromes (Table 6.2)3–10

Inherited “paroxysmal” disorders that can include choreiform movement (see Table 6.3 for clinical overview)11

Inherited “paroxysmal” disorders that can include choreiform movement (see Table 6.3 for clinical overview)11

Helpful Tips for Managing Functional and Behavioral Problems in Patients With Huntington’s Disease

Sporadic forms of chorea

Sporadic forms of chorea

Essential chorea is adult-onset, nonprogressive chorea in a patient without a family history or other symptoms suggestive of HD and without evidence of striatal atrophy. “Senile chorea” is essential chorea with onset after age 60 without dementia or psychiatric disturbance.

Essential chorea is adult-onset, nonprogressive chorea in a patient without a family history or other symptoms suggestive of HD and without evidence of striatal atrophy. “Senile chorea” is essential chorea with onset after age 60 without dementia or psychiatric disturbance.

Infectious chorea has been described as an acute choreiform manifestation of bacterial meningitis, encephalitis, tuberculous meningitis, aseptic meningitis, HIV encephalitis, or toxoplasmosis.

Infectious chorea has been described as an acute choreiform manifestation of bacterial meningitis, encephalitis, tuberculous meningitis, aseptic meningitis, HIV encephalitis, or toxoplasmosis.

Postinfectious/autoimmune chorea12

Postinfectious/autoimmune chorea12

Sydenham disease (St. Vitus’ dance, the eponym sometimes used by patients) is related to infection with group A streptococci, and the chorea may be delayed for 6 months or longer. The distribution is often asymmetric. The chorea can be accompanied by arthritis, carditis, irritability, emotional lability, obsessive–compulsive disorder, or anxiety. Serologic testing reveals elevated titers of anti-streptolysin O (ASO).

Sydenham disease (St. Vitus’ dance, the eponym sometimes used by patients) is related to infection with group A streptococci, and the chorea may be delayed for 6 months or longer. The distribution is often asymmetric. The chorea can be accompanied by arthritis, carditis, irritability, emotional lability, obsessive–compulsive disorder, or anxiety. Serologic testing reveals elevated titers of anti-streptolysin O (ASO).

Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with anti-phospholipid syndrome (characterized by migraine, chorea, and venous and/or arterial thrombosis). The patient tests positive for anti-phospholipid antibodies and anti-cardiolipin antibodies. Other features are spontaneous abortions, arthralgias, Raynaud phenomenon, digital infarctions, transient ischemic attacks, and cardiovascular accidents.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with anti-phospholipid syndrome (characterized by migraine, chorea, and venous and/or arterial thrombosis). The patient tests positive for anti-phospholipid antibodies and anti-cardiolipin antibodies. Other features are spontaneous abortions, arthralgias, Raynaud phenomenon, digital infarctions, transient ischemic attacks, and cardiovascular accidents.

Chorea gravidarum is often associated with a recurrence of systemic lupus erythematosus or with a prior history of Sydenham chorea but can also be associated with other metabolic or systemic disturbances.

Chorea gravidarum is often associated with a recurrence of systemic lupus erythematosus or with a prior history of Sydenham chorea but can also be associated with other metabolic or systemic disturbances.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree