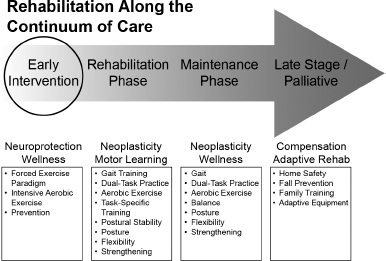

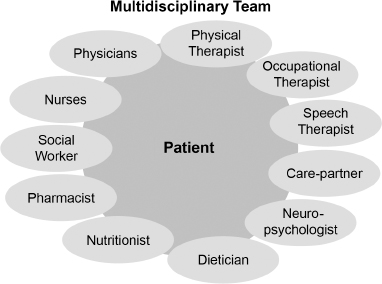

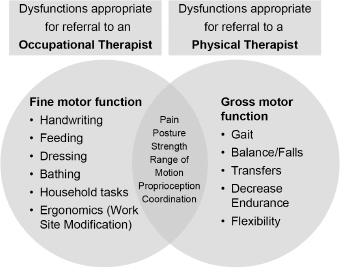

17 PHYSICAL AND OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY Patients with movement disorders can develop motor, cognitive, and behavioral impairments that can lead to a loss of functional ability and independence in activities of daily living and result in decreased quality of life. Physical and occupational therapy can help to prevent and treat these symptoms, and to rehabilitate patients in order to restore maximum movement, functional mobility, and participation in work, family, and society. The aim of therapy is to maximize independence and quality of life at the time of the diagnosis and throughout the course of the disorder. This chapter is designed to focus on the role of physical and occupational therapists in the care and management of patients with movement disorders. We first discuss the emerging role of exercise in the management of Parkinson’s disease (PD). We subsequently discuss the roles of physical and occupational therapists as part of a multidisciplinary team. Finally, we discuss the specific issue of falls in people with movement disorders. Movement disorders are grouped together on the basis of the similarity of the clinical presentation. Many movement disorders represent progressive, multisystem neurodegenerative processes that can result in increased disability over time. A few important conceptual points are relevant to the clinical care of patients: Exercise is an important part of healthy living for everyone, regardless of the presence of any movement disorder. Regular exercise is a vital component to maintain balance, mobility, and activities of daily living in people with movement disorders. Upon diagnosis, people with movements disorders have already reduced their overall level of physical activity and often have withdrawn from recreational and leisure activities despite minimal reports of disability. Individuals with PD show a significant decline in their levels of physical activity in the first year after their diagnosis. Inactivity can accelerate the degenerative process and result in multiple preventable secondary impairments. Figure 17.1 Animal models have shown that physical activity may directly impact the neurodegenerative process, likely mediated by brain neurotrophic factors and neuroplasticity. Potential mechanisms include angiogenesis, synaptogenesis, reduced oxidative stress, decreased inflammation, and improved mitochondrial function. Vigorous aerobic exercise has been associated with a reduced risk for developing PD and improved cognitive function. This type of exercise has been shown to increase the volume of gray matter in the brain, and to improve functional connectivity and cortical activation related to cognition. There is also emerging evidence that exercise can improve corticomotor excitability in people with PD.9–12 With the potential benefit of neuroplasticity and neuroprotection, exercise is an important part in the medical management in people with PD (Figure 17.1). The management of movement disorders is best approached with a patient-centered multidisciplinary team (Figure 17.2 and Table 17.1). Physical therapists and occupational therapists have different areas of expertise (Figure 17.3), and a physician referring a patient to one of these specialists should be familiar with the domains of expertise of each.23,24 THE ROLE OF THE PHYSICAL THERAPIST. Postural instability and dysfunction of gait and balance are common symptoms in many movement disorders. The goal of physical therapy is to partner with patients to develop exercises and strategies that maintain or increase activity levels, decrease rigidity and bradykinesia, optimize gait, improve balance and motor coordination, and develop an individualized exercise program to prevent secondary impairments (Figures 17.4 and 17.5; Table 17.2). WHEN TO REFER TO A PHYSICAL THERAPIST. Upon diagnosis, referral to a physical therapist for an early intervention exercise program is vital in the management of most people with movements disorders. The benefits of early referral include the following: Figure 17.2 Table 17.1 Function or Problem to Be Addressed Specialist Dexterity, gait, balance Physical and occupational therapists, physiatrists Swallow function, dysarthria, hypophonia Speech and swallow clinicians, laryngologists, gastroenterologists Cognitive decline Neurologists, geriatricians, neuropsychologists, pharmacists, occupational therapists Mood disorders Neurologists, primary care physicians, clinical psychologists, sex therapists, psychiatrists Figure 17.3 Figure 17.4 Figure 17.5 Table 17.2 Deficit Treatment Physical capacity Cardiovascular endurance training Rigidity (axial extension and rotation) Range of motion and flexibility exercises Weakness (trunk and lower extremity extensors) Resistance and functional strength training Postural instability (anticipatory and reactive postural responses) Balance training (see Figure 17.4), postural adjustment exercises, cognitive strategies training Gait dysfunction (bradykinesia, freezing, festination) Whole-body activation Retraining in acceleration and large-amplitude functional movement Treadmill training Adaptive stepping techniques • Visual cues (ie, stepping over an object or caregiver’s foot, inverted cane, using a laser pointer to create a dot on floor as a target; see Figure 17.5) • Auditory cues (ie, metronome, counting aloud, walking with music) • Internal cues (for patients with mild disability who are able to concentrate on step-by-step activity rather than continuous gait). Patients can stop/pause to regroup/reset and start again with one good step. Declining ability to perform activities of daily living Exercises to improve bed mobility and transfer Exercises to improve performance in leisure and recreational activity

Forms of parkinsonism such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), multiple systems atrophy (MSA), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (CBDG) result in relatively rapid rates of decline.1–4

Forms of parkinsonism such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), multiple systems atrophy (MSA), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (CBDG) result in relatively rapid rates of decline.1–4

Idiopathic PD usually has a relatively slower rate of progression, but disabling deficits that are unresponsive to medication will develop over time in a majority of patients.5

Idiopathic PD usually has a relatively slower rate of progression, but disabling deficits that are unresponsive to medication will develop over time in a majority of patients.5

THE ROLE OF EXERCISE IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Evidence-Based Benefits of Exercise in People With Parkinson’s Disease

Improved physical function

Improved physical function

Improved quality of life

Improved quality of life

Increased strength

Increased strength

Improved balance

Improved balance

Increased walking speed and stride length

Increased walking speed and stride length

Increased flexibility and posture

Increased flexibility and posture

Potential Motor and Nonmotor Targets of Exercise

Prevention of cardiovascular complications

Prevention of cardiovascular complications

Reduced risk for osteoporosis

Reduced risk for osteoporosis

Improved cognitive function

Improved cognitive function

Prevention of depression

Prevention of depression

Improved sleep

Improved sleep

Decreased constipation

Decreased constipation

Decreased fatigue

Decreased fatigue

Improved functional motor performance

Improved functional motor performance

Improved drug efficacy

Improved drug efficacy

Optimization of the dopaminergic system

Optimization of the dopaminergic system

Summary of the rehabilitation approach across the continuum of Parkinson’s disease.

Disease Modification

Ingredients to Promote Neuroplasticity and Neuroprotection

Exercises based on motor learning

Exercises based on motor learning

High level of repetition

High level of repetition

Task-specific training

Task-specific training

“Forced” aerobic exercise

“Forced” aerobic exercise

“Forced-use” exercise

“Forced-use” exercise

Complexity: dual tasking

Complexity: dual tasking

Evidence-Based Approach to Exercise for Parkinson’s Disease

Progressive aerobic training

Progressive aerobic training

Treadmill training

Treadmill training

Pole walking

Pole walking

High-effort, whole-body, large-amplitude movements (eg, Lee Silverman Voice Therapy–BIG [LSVT-BIG])

High-effort, whole-body, large-amplitude movements (eg, Lee Silverman Voice Therapy–BIG [LSVT-BIG])

Spinal flexibility

Spinal flexibility

Agility (coordination and balance training)

Agility (coordination and balance training)

Augmentation of proprioceptive feedback

Augmentation of proprioceptive feedback

Kinesthetic awareness training

Kinesthetic awareness training

High-effort rate or strength training

High-effort rate or strength training

Dual-task training

Dual-task training

Dancing, tai chi, music, boxing12–22

Dancing, tai chi, music, boxing12–22

PHYSICAL THERAPY AND OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY IN A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT

Differentiating the Roles of the Physical Therapist and the Occupational Therapist

The multidisciplinary team providers.

Members of the Management Team and Their Respective Roles

Establish baseline physical functional status with the use of standardized outcome tools

Establish baseline physical functional status with the use of standardized outcome tools

Develop an individualized exercise program

Develop an individualized exercise program

Identify motor dysfunction as well as impairments that can be addressed through exercise and behavioral modification

Identify motor dysfunction as well as impairments that can be addressed through exercise and behavioral modification

Develop effective gait and balance strategies, which is more easily done before significant disease progression ensues

Develop effective gait and balance strategies, which is more easily done before significant disease progression ensues

Differentiating the roles of the physical therapist and occupational therapist.

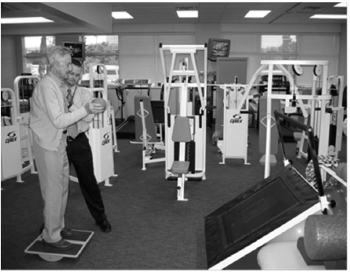

Example of balance training. The patient is standing on a “wobble board.” The upper extremities are occupied with a task to mimic the multitasking necessary in many activities of daily living.

Educate patients and care partners about the disease process and its motor and nonmotor consequences

Educate patients and care partners about the disease process and its motor and nonmotor consequences

Reduce the risk for and fear of falling

Reduce the risk for and fear of falling

Example of a stepping exercise. A patient with gait freezing develops a motor program of stepping by using visual cues.

Physical Therapy Interventions

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neupsy Key

Fastest Neupsy Insight Engine