3 Clinical Features of Brain Tumors

Pathophysiology of Symptoms and Signs

Symptoms and signs are caused by a variety of mechanisms, many of which may be active in a given patient. It is the combination of these mechanisms that produce the clinical syndromes observed in patients.1,2

HERNIATION SYNDROMES

There are five common herniation syndromes.

Uncal herniation

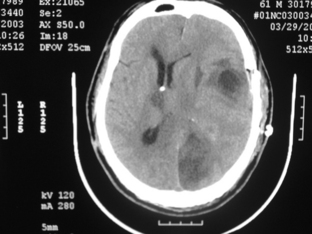

occurs when a mass lesion causes the uncus of the temporal lobe to herniate through the tentorium cerebelli. The key clinical sign of uncal herniation is ipsilateral oculomotor nerve palsy with a fixed and dilated pupil due to compression by the medial temporal lobe. Typically, a contralateral hemiparesis is also seen, but a false localizing sign of uncal herniation is an ipsilateral hemiparesis due to displacement of the brainstem to the opposite side causing compression of the contralateral cerebral peduncle against the tentorium (Kernohan notch). Additionally, unilateral or bilateral posterior cerebral artery occlusion can occur at the tentorial notch, leading to a homonymous hemianopsia or cortical blindness (Fig. 3-1).

Upward brainstem herniation

is seen in patients with posterior fossa tumors, where the superior surface of the vermis and midbrain are pushed upward, compressing the dorsal mesencephalon and cerebral aqueduct. Dorsal midbrain compression leads to impairment of vertical eye movements and a reduced level of consciousness.2,3

Factors Determining Symptoms and Signs

There are several biological factors intrinsic to the tumor itself that affect the clinical manifestations of the disease (Table 3-1). The general location of the tumor, supratentorial vs. infratentorial, or cortical vs. subcortical, will affect the presentation. If the tumor is extraaxial, it will compress the underlying brain tissue instead of destroying it as a parenchymal tumor might. The rapidity of growth will determine how soon a tumor will manifest; slow-growing tumors are insidious. Discrete tumors usually present with focal localizing symptoms as compared to diffusely infiltrative ones. The size of the tumor can affect symptoms in that even large tumors in relatively silent areas of the brain may be asymptomatic, whereas small tumors in other areas, for instance the brainstem, will present early. Some tumors can cause non-neurological symptoms, such as pituitary tumors via secretions.

TABLE 3-1 Factors Determining the Signs and Symptoms of Brain Tumors

Neurologic Symptoms and Signs

Regardless of tumor location, patients can have generalized and/or lateralizing symptoms. Generalized symptoms are non-localizing and can include headache, seizures, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, mental status changes, and visual obscurations. Focal symptoms reflect the intracranial location of the tumor and include seizures, hemiparesis, diplopia, aphasia, vertigo, incoordination, sensory abnormalities, and dysphagia (Table 3-2). Finally, there are false localizing signs, which are caused by raised intracranial pressure and which may include diplopia, tinnitus, and hearing or visual loss. These signs may suggest focal neurologic dysfunction, but actually reflect a generalized increase in intracranial pressure.

TABLE 3-2 Focal Signs and Symptoms of Brain Tumors (adapted from DeAngelis50)

GENERALIZED SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

Headache

Headache is a very common symptom leading to neurologic referral, and when associated with a normal neurologic examination, is rarely due to a brain tumor. Intracranial neoplasms account for a small percentage (less than 10%) of patients with headache, but headache occurs in about 50% of patients with brain tumors,4,5 and in some studies the prevalence has been shown to be as high as 60% to 70%.6,7 However, most of these patients have accompanying neurologic signs. Headache is the sole presenting complaint in only 8% of patients with brain tumors.6,8 A new-onset headache of sufficient severity that the patient seeks medical assistance, in an adult without a prior history of headache, requires a full investigation including neuroimaging.

Headache related to brain tumor is a result of raised intracranial pressure causing stimulation of pain-sensitive structures in the cranial vault (Table 3-3).9,10 The pain-sensitive intracranial structures include the pachymeninges and all vascular structures in the brain; the brain parenchyma itself is insensitive to pain. Headaches occur due to involvement of the meninges and vessels by direct tumor invasion, inflammation or edema resulting from the tumor, or traction or pressure on the pain-sensitive structures by the tumor. Headache in brain tumor patients can be nonspecific, or may resemble tension-type headache, migraine, or a “classic tumor headache,” which occurs in the morning and improves spontaneously over the course of the day. Tumor headache may get progressively severe over time; this is often related to an increase in the surrounding edema rather than the actual size of the tumor.4,5

TABLE 3-3 Factors Contributing to Headache in Patients with Brain Tumor

The most common headache in brain tumor patients is similar to tension-type headache, and is characterized as a dull ache or pressure-like pain.4,6 These headaches are usually bifrontal and are often worse on the side ipsilateral to the tumor. Nausea or vomiting may be associated, and usually indicate generalized elevation of intracranial pressure. However, headaches that mimic classical migraine can also occur in patients with brain tumors. They are seen predominantly in patients with a history of migraine who then develop a brain tumor. These headaches may be associated with nausea and vomiting which, in these cases, do not necessarily indicate raised intracranial pressure.4 In some patients, a brain tumor can present as the worst headache of their life; this may be associated with intratumoral hemorrhage which is accompanied by neck stiffness, vomiting, mental status changes, and focal signs such as hemiparesis. More often, however, these severe headaches are not due to a bleed. In other cases, compression of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve or involvement of the nerve by tumor results in the typical pain of trigeminal neuralgia. Also, Gasserian ganglion involvement may cause neuralgia-type pain in the V2-3 distribution. Rarely, occipital neuralgia has been reported.11,12 Some authors have demonstrated that there is a tendency for pulsatile pain with meningioma.6 This may be related to the increased vasculature of meningiomas and innervation of the blood vessels by the trigeminal nerve.

The most common headache site in brain tumor patients is frontal, and is usually bilateral.4 This is seen commonly with supratentorial tumors or with diffuse elevation of intracranial pressure. Occipital headaches, with or without neck pain, are seen in infratentorial tumors or when there is base of skull involvement by tumor, but tumors in these locations may also give rise to frontal pain. Thus, headache has poor localizing value. However, lateralization of the tumor can be reliable when the patient complains of headache on one side of the head or the other.

Headache caused by raised intracranial pressure is distinctive in its severity, its association with nausea and vomiting, and its resistance to common analgesics.4 There may be associated papilledema, which is usually seen in children or young adults with raised intracranial pressure. Paroxysmal headaches can be seen in association with tumors of the third ventricle or pedunculated tumors intermittently obstructing CSF flow; occasionally, they are precipitated by changes in position. Rarely, Brunn syndrome can develop, which is characterized by attacks of sudden and severe headache, vomiting, and vertigo, triggered by head movement.13 Episodic headaches may also be indicative of plateau waves. These occur in patients with elevation of baseline intracranial pressure (which may be asymptomatic) and episodic symptoms, including headaches, that are triggered by a change in body position. The act of assuming the upright posture triggers a marked increase in intracranial pressure due to loss of autoregulation. The brisk rise in intracranial pressure usually resolves on its own; however, it causes transient symptoms while the pressure is elevated, typically to a level exceeding systolic blood pressure. Generally, these symptoms last five to ten minutes and resolve spontaneously. In addition to headache, common symptoms that occur with plateau waves include visual loss or obscurations, lightheadedness, loss of tone in the legs and even loss of consciousness. These symptoms are often confused with seizures, but a careful history makes the diagnosis clear. Exacerbation of headache may also occur with changes in intracranial pressure, such as with coughing, sneezing, performing Valsalva maneuver, exertion, or sexual activity; however, these exacerbations are uncommon in brain tumor patients.14

Headaches occur more commonly with infratentorial than supratentorial tumors.5,7,8 Dural-based tumors may present with headache. Subdural hematoma from dural metastases can also give rise to headache. Often, patients with supratentorial tumors without raised intracranial pressure do not have headaches despite large tumor size, and if they do have headaches, the pain is likely to be intermittent and less severe than with infratentorial tumors.4 Young patients are also more likely to suffer from headaches than older patients, possibly because age-related atrophy allows better compensation for the growing mass.

Patients with a preexisting history of headache are predisposed to develop secondary headaches in the presence of brain tumors.4,6 They are likely to suffer from headaches even when controlled for raised intracranial pressure. A change in quality, severity, and location of a pre-existing headache should be considered ominous and always warrants an evaluation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree