CHAPTER 76 CLINICAL SPECTRUM: DEFINITION AND NATURAL PROGRESSION

Once a neurological illness common in the Western and developed world, multiple sclerosis (MS) is now being increasingly reported from most parts of the world, including tropical countries. Marked by ambulatory disabilities caused at a relatively early age, MS is complicated by unpredictability of attacks and progression. We discuss the definition, clinical features, and natural progression of MS in this chapter. The major inputs for natural progression in this chapter are courtesy of the natural history database at the London Multiple Sclerosis Clinic, London Health Sciences Center, University of Western Ontario, London Ontario, Canada, with over 26,000 patient-years of studies.

CLINICAL PHENOTYPES OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

There are no specific clinical or paraclinical markers for MS. Among the many classifications that have been proposed, we chose for the purpose of this chapter the phenomenological classification initially suggested by McAlpine,1 later reviewed by an international survey,2 although there was no unanimity of opinion:

The terms relapsing progressive or progressive relapsing are self-explanatory, but are unnecessary additions to the phenotypes, and hence are best avoided.3–5

An acute attack or exacerbation or relapse, as defined by Schumacher and colleagues,6 is a focal disturbance of function, affecting a white matter tract, and lasting for more than 24 hours. Typically, an acute exacerbation tends to progress over a period of a few days, reaching a maximum in less than 1 week, and then slowly resolving. Complete recovery from an attack is common early in the disease.

The mean annual frequency of relapses has been shown to be between 0.4 and 1.1 relapses per patient per year.7–12 The average attack rate in the first year was found to be 1.5 to 2.3 relapses per patient per year, falling with age and duration13 of disease. The relapse frequency starts to decrease by the second year of the disease.14 The interval between two relapses can be a minimum of 1 month (as defined by Schumacher6) to more than 35 years. A typical relapse lasts for about 6 weeks. Recovery starts by the second week in most patients. The earlier a relapse starts to recover, the better is the total recovery.14

A pseudo-relapse is acute-onset worsening of preexisting symptoms or signs or reappearance of symptoms or signs in the same location as a prior attack, with lesser or equal severity. The usual causes are physiological, primarily fever, urinary tract infection, or vaccination. Table 76-1 compares true and pseudo-relapses.

TABLE 76-1 True Relapses Versus Pseudo-relapses

| Parameter | True Relapses | Pseudo-relapses |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Acute/subacute | Acute more likely |

| Duration | Weeks likely | Days rather than weeks |

| Previous deficit | Not necessary | Likely |

| Fever associated | Not likely | Usually |

Courtesy of Paty DW, Ebers GC: Multiple Sclerosis. Contemporary Neurology Series (50). Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1997.

Relapses and their associations or precipitating factors have been studied by many. Relapses have been claimed15 but unproved to be more common in warmer months. Large studies have not documented significant reduction in the relapse rates during pregnancy, but the overall relapse rate is higher in the first 6 months postpartum, especially during the first 3 months.16–21 Relapse rates are not influenced by breastfeeding.19

In some instances, relapses have been associated temporally with immunization.22 Large studies failed to confirm increased relapse risk after immunization in the MS population.23 However, in clinical practice, postimmunization relapses have been documented.

On the other hand, infections have been found in most studies to be temporally associated with increased relapse rates in the postinfectious phase,24–26 and it is a common observation that MS patients present typically 3 to 4 weeks after an infection, with a true or pseudo-relapse. Relapse rates were not increased postsurgically or postanesthesia in most studies.27,28 Stress and life adversities have been claimed to be associated with increased relapse risk, but this is difficult to assess objectively.29–31 There are no data to support the notion that physical trauma can precipitate relapses or “unmask” dormant MS that otherwise would have remained silent.15,27,28,32

A small number of patients complain of deterioration in functional capacity in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Slight temperature elevation during this phase may be responsible,33 and tiredness and fatigue may worsen preexisting deficits.

Although the above categories encompass most clinical presentations of MS, individual variations are very common. There may be attacks in PPMS, and sometimes SPMS may begin after one single attack, labeled single attack progressive MS.34

Benign MS: This subcategory of RRMS tends to be common in women with a younger age of onset who had sensory symptoms as the presenting feature. An Expanded Disability Scale Score (EDSS) score of less than 3 for more than 10 years of MS diagnosis was considered as benign in a study by Redekop and Paty,35 and they found 24% of the 536 patients studied in British Columbia belonged to this category. Freedom from either attacks or progression for decades can be considered to be typical of benign MS. It is most easily recognized in hindsight.

Acute malignant MS:14 Some patients often have a polysymptomatic onset and progress rapidly to severe disability, death, or both within months (very rare) or a few years (uncommon). Even this most malignant clinical course cannot be reliably predicted at onset. The distinction between acute malignant MS and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis can be difficult. New lesions manifest clinically or on MRI and progression beyond 2 months are features more consistent with a diagnosis of MS than acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In addition, in the adult, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is much less common than MS, so that most patients with the acute malignant progression will turn out to have MS.

Opticospinal MS (Devic’s disease, neuromyelitis optica):14 Reported very frequently from the orient, opticospinal MS predominantly involves attacks and progressive worsening in the optic and spinal systems. This variant is characterized by an earlier age of onset, early progression, minimal or no recovery of neurodeficit after an attack, and poor prognosis.

Lennon and associates36 from the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, studied 102 North American and 12 Japanese patients with neuromyelitis optica against controls, including MS, optic neuritis, myelopathies, and other conditions, for the presence of neuromyelitis optica IgG antibodies. They claim that this is a specific marker autoantibody for neuromyelitis optica, distinguishing the latter from MS. Based on the prevalence of this marker, the group also comments that Asian opticospinal MS is the same entity as neuromyelitis optica.

Progressive and chronic cerebellar MS have both been believed to be variants of PPMS.

Childhood MS is rare (less than 4% of cases). Youngest cases reported include 10-month-old, 24-month-old, and 4-year-old children. This variant is further more frequent in females (3:1). Vertigo is a frequent presenting feature. Most patients will have a remitting sensory onset. Deterioration is slower, and the youngest patients have the best prognosis for disability. About 82% of childhood MS patients have positive oligoclonal banding in the cerebrospinal fluid. In an excellent review of childhood MS, Banwell37 writes that the onset of progression in MS beginning before the age of 16 years is later as compared to adult-onset MS, by an average of 15 years.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

The common presenting symptoms in MS are summarized in Table 76-2.

TABLE 76-2 Common Presenting Multiple Sclerosis Symptoms

Consciousness and Cognition

Cognitive and psychiatric changes in MS have traditionally been underemphasized. Studies have demonstrated that minor deficits in cognition are quite common (up to 70%), even in early MS (up to 50%).38–40 Dementia can be an accompaniment of severe disabling MS of long-term duration. Lesions seen in the corpus callosum on the MRI scan are also well correlated with cognitive defects. Periventricular lesions and the width of the third ventricle are described to be the most frequent MRI correlates with cognitive deficits.41

Euphoria is commonly a manifestation of subtle or obvious cognitive change.42 Focal cortical deficits such as aphasia, apraxia, and agnosias have been reported uncommonly. The most frequent cognitive abnormalities in MS are subtle defects in abstraction and memory,43–46 attention, and word finding.47 These are usually associated with emotional lability and decreased speed of information processing.45,46

Traditional tests for dementia designed for use in neuronal degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease are not sensitive to the changes seen in MS.47 The most sensitive bedside measures for cognitive defects in MS have been tests such as the repetition of seven numbers forward or backward, serial 7s or 3s, and visual recognition tests.48,49 Verbal working memory is specially susceptible to impairment in MS.50

Mood disorders are frequent in patients with MS. An association may exist between MS and bipolar disorder.51–53 A survey in the University of British Columbia Multiple Sclerosis clinic shows that 38% of patients with MS have been depressed or could have bipolar disorder.52 Other forms of psychosis are rare but can be seen. Some patients develop hypomanic behavior with steroid therapy, commonly used to treat relapses.

Sleep Disturbances

Studies have shown that patients with MS are more likely than control subjects to have sleep disturbances.54 The sleep problems may be due to nocturnal spasms. They may also be a major contributor to fatigue that is so common in MS. Overall, patients with MS have poor sleep efficiency with frequent awakening. Periodic leg movements are also frequent and may contribute to the sleep disturbances.55 Incontinence and other bladder symptoms like nocturia may further deteriorate sleep quality and duration. Narcotic symptoms are common.56

Fatigue

Fatigue, a frequent and disabling feature of MS,57,58 is considered a state of exhaustion distinct from depressed mood or physical weakness.59

Seizures

Convulsive seizures occur in about 2% of MS patients. One half of the seizures are probably due to the MS lesion itself, and the other one half are due to chance association. Seizures in MS are usually easily controlled with anticonvulsants. Patients with seizures tend to have more subcortical or temporal lobe lesions or both than do control MS patients without seizures.60

Headache

Headache is a frequent complaint in MS.61 Occasionally, acute headache occurs in the pseudotumor, acute-onset type of relapse. One type of headache seen sometimes in MS is hemicranial and may be associated with an acute pontine lesion.62 Most patients with MS who have headache probably have tension headache due to muscle spasm in the neck and the scalp muscles or have migraine or are depressed.14 Pain on eye movement due to optic neuritis may also be responsible for headache.63

Cranial Nerve Involvement in Multiple Sclerosis

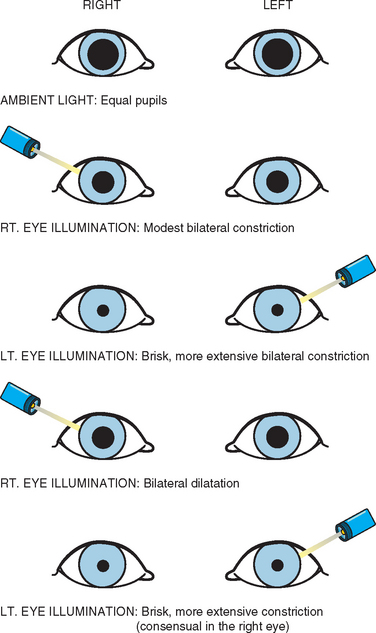

Pupillary Defects

Most of these defects are related to the afferent pupillary defect (or Marcus Gunn pupil) (Fig. 76-1). Fixed dilated pupils associated with or independent of other elements of a third nerve palsy are extremely rare. Central Horner’s syndrome is occasionally seen.64

Loss of Vision

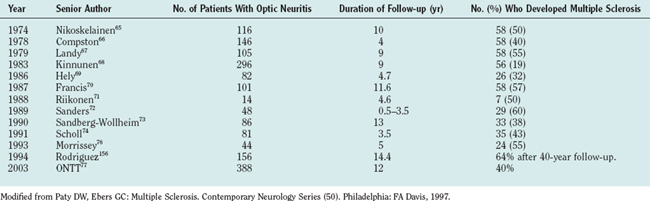

Acute loss of vision due to optic neuritis is a common feature of MS and is mostly unilateral. This is also a common clinical presenting feature. About 50% to 70% patients with optic neuritis proceed to develop MS in future; Table 76-3 shows major trials documenting this.

Optic neuritis may be retrobulbar, chiasmal, or even retrochiasmal. Many patients recover functionally normal vision after optic neuritis, even in the face of severe residual optic atrophy.78,79 Visual field deficits in MS tend to be central, but occasionally a clinician can encounter paracentral or peripheral scotomata or quadrantanopic or hemianopic defects. Homonymous hemianopias can occur in MS but are unusual; when seen, they should raise the possibility of coexistent tumor or vascular disease. Fortunately, legal blindness in MS is unusual (less than 5%).80

Many patients experience a dimming, blurring, or obscuring of vision associated with exercise and heat. Uhthoff first described this symptom.81 The transient appearance or worsening of neurodeficits (most typically, visual impairment, but any functional system can be involved) on exposure to any form of heat (atmospheric, hot shower, exercise, fever, or even hot food or drinks) is known as Uhthoff’s phenomenon, and is a very common accompaniment to relapses.

Pain is usually seen as an accompaniment to acute optic neuritis82 and may be due to traction of the origins of the superior and medial recti on the optic nerve sheath. Besides the blurring of vision and central scotoma, relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), color blindness, and sometimes Pulfrich phenomenon are clinical signs found in most MS patients. The Pulfrich phenomenon83 is a subjective correlate of conduction delay in one optic nerve. A pendulum oscillating in front of a normal individual will appear to traverse an ellipse if a neutral density filter or a piece of dark glass is placed over one eye. A patient with unilateral optic neuritis may see this illusion without a filter: the disease delays conduction just as does the filter.

Anosmia may be found on examination in many MS patients,84 although this may not be voluntarily reported by the patient.

Unilateral or bilateral loss of taste is infrequent. Paty and Ebers have observed this in several patients, and this was the presenting complaint in one patient. This symptom always remitted,14 in their observation.

Ocular Motility Disorders in Multiple Sclerosis

The most common in this group is nystagmus.85–88 The frequency of occurrence of nystagmus in MS has been reported to be between 28.3% and 63%. Nystagmus in MS may be acquired pendular, gaze evoked, rebound, torsional, periodic alternating, or another type. Optokinetic nystagmus is never impaired in isolation.14 The most common is the nystagmus that accompanies internuclear ophthalmoplegias.

In many MS patients, inappropriate initiation of saccadic eye movements during fixation or change in gaze position results in saccadic intrusions (square wave jerks, saccadic pulse, and double saccadic pulses) and saccadic oscillations (macro-square wave jerks, macrosaccadic oscillations, and ocular flutter).89 A square wave jerk consists of a small amplitude conjugate saccade away from fixation followed by a saccade back to fixation after a latency delay of about 200 milliseconds.

Oculomotor nerve pareses are uncommon presentations of MS but are known, and Paty and Ebers14 reported it as an initial presentation in two cases.

Paresis of fourth cranial nerve as an isolated feature is rare.14

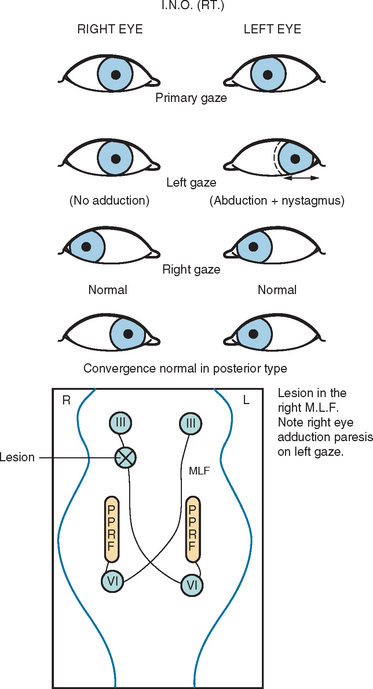

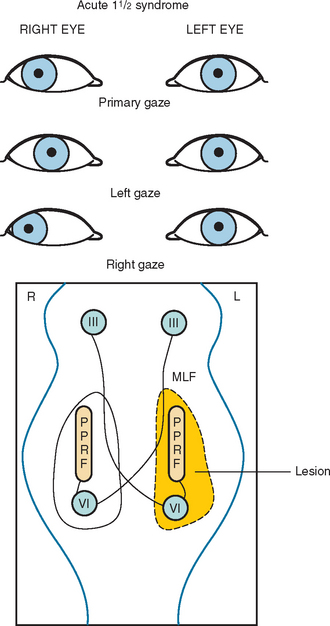

Another common abnormality of eye movements in MS is internuclear ophthalmoplegia, bilateral (most frequent) or unilateral.14 Internuclear ophthalmoplegia manifests as partial or complete paresis of adduction on the side of lesion, with ataxic nystagmus in the other (abducting) eye (Fig. 76-2). Skew deviation and vertical nystagmus (upbeat on gaze up or downbeat on gaze down) may also occur. Bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegias are associated with vertical nystagmus in one or both directions. One-and-a-half syndrome (Fig. 76-3) and wall eyed bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia (Fig. 76-4) have been reported often in the MS literature. Lateral gaze pareses are also a common manifestation of MS. Visual suppression of the vestibulo-ocular reflex is often abnormal.

Trigeminal Motor and Sensory Symptoms

Facial sensory loss can occur in as many as 10% of MS patients.14 This can be a presenting feature as in a relapse or a lingering transient symptom. Trismus has also been reported.90 Trigeminal neuralgia is discussed later in the section on pain.

Facial Palsy

The acute development of a peripheral facial nerve paresis is an uncommon but recognized feature of MS.14 It occurs in less than 4% of patients and almost always recovers spontaneously and completely. Recovery from an MS-associated facial palsy is usually not associated with autonomic abnormalities such as crocodile tears; however, aberrant reinnervation, myokymia, and the phenomenon of intrafacial synkinesis are all commonly seen. Acute facial palsies are accompanied by other brainstem findings such as a sixth nerve palsy, lateral gaze palsy, or deafness. Paty and Ebers have seen one case with remitting bilateral facial myokymia that was disabling because the patient could not open his eyes. The symptom responded to carbamazepine therapy.

Deafness

Central lesions resulting in impaired hearing commonly occur, but persistent complete deafness is unusual in the absence of another etiology.91

Vertigo

This is a relatively common symptom. As many as 50% of patients have intermittent episodes of vertigo. In a review of initial symptoms in MS by Paty and Ebers,14 it was found that onset with vertigo as a symptom favored a long-term, more benign outcome.

Dysphagia

Mild dysphagia is common.14 It usually coexists with dysarthria, often in the setting of pseudobulbar palsy. Dysphagia is usually due to desynchronization of the swallowing mechanism.

Dysarthria

Cerebellar dysarthria is a common component of relapses but is usually late to occur in the progressive phase.14 There is intention tremor of the voice, which can be demonstrated by having the patient sustain a vowel sound for 10 to 15 seconds. The variation in the intensity and sometimes pitch of the sound is easily heard; the frequency is usually 5 to 7Hz, similar to other cerebellar tremors. Patients may show elements of combined cerebellar and pseudobulbar (spastic) dysarthria. Some patients have only spastic speech. Pseudobulbar dysarthria is caused by spastic vocal cords, which result in a high-pitch, low-volume speech, in which consonants are slurred. These patients do not have the oscillating tremor or the explosive variability associated with cerebellar speech. Some patients with MS develop dysarthria after several minutes of sustained speech. This effort-induced symptom tends to recover after a few minutes of rest.

Breathing Disturbance

Rarely, MS patients have a peculiar air hunger, usually associated with severe fatigue. Serious respiratory problems other than pneumonia and bronchitis are uncommon. Howard and colleagues92 described 19 patients who developed respiratory complications an average of 5.9 years after onset. Of these, 12 required mechanical ventilatory support, and 5 recovered. Six patients died after an average of 17.7 months.

Motor and Sensory Findings

Sensory loss is the most frequent of all neurological findings in MS.14 It is present in 90% of patients at some time during the clinical course. The distribution of sensory loss between upper and lower extremities can vary. Isolated transient facial numbness is frequently seen. Unremitting unilateral facial numbness is more likely due to isolated trigeminal neuropathy. It is also unusual for a sensory segmental level of pain or temperature loss to persist, even in advanced cases. However, during acute exacerbations, a sensory level can be seen in 10% to 15% of patients. When persistent abnormalities in touch, pain, and temperature sensation do occur, the pattern of loss is likely to be a patchy one. In contrast, posterior column or discriminatory sensation testing can be very useful. From 85% to 95% of patients with MS have an abnormality in posterior column sensation at some time during their clinical course. The sensation loss is often prominent in the lower extremities, but bilateral predominant upper extremity impairment is common.

The useless hand syndrome (Table 76-4) is a particularly interesting sensory manifestation that is usually seen in patients with predominant upper extremity proprioceptive loss.93 Even though the useless hand syndrome can occur in other disorders, it is highly characteristic of MS. It is common to see young adults with MS develop lack of discriminatory sensation in one upper extremity to the extent that the extremity becomes functionally useless despite normal crude sensation, motor, and cerebellar function. The useless hand syndrome in MS usually resolves spontaneously, although it can be extremely disabling while present. It usually begins with either tingling or lack of fine sensory discrimination in the fingers. The patient notices an inability to recognize objects in the pocket or purse. The patient can then develop impairment of hand function because of the inability to distinguish various subtleties in tactile sensation and lack of feedback control of movement.

TABLE 76-4 Useless Hand Syndrome Characteristics

Lhermitte’s Symptom

This is the occurrence of tingling and “electric current-like” sensation in the arms, down the back, into the legs, or in all the three areas, associated with forward flexion of the neck.14,94,95 This symptom occurs in 3% of patients at the onset of the disease and probably occurs in 30% to 40% of patients overall at some time during the clinical course. It is most frequently associated with MS, although it is not specific to this disease. Symptoms are usually precipitated by forward flexion of the neck but can also be brought on by forward flexion of the spine or even other minor movements. This symptom may sometimes occur spontaneously. In unusual circumstances, Lhermitte’s symptom can be disabling in the absence of other significant neurological deficits, usually because of its frequency, duration, or intensity. Such disabling symptoms usually respond somewhat to gabapentin, carbamazepine, or benzodiazepine therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree