INTRODUCTION

Memory loss and dementia are nearly universal concerns in the age-ing sector of our population1. In practice, differentiating the normal age changes from those of early Alzheimer’s disease can be daunting. Advances in clinical diagnostics and laboratory imaging methodolo-gies facilitate this process2; however, there remains no definitive diagnostic biological test for Alzheimer’s disease or for other related neurodegenerative conditions. Ultimately, the diagnosis of a cogni-tive disorder rests on an informed clinical examination. A thorough neurobehavioural examination and more detailed neuropsychologi-cal assessment, when indicated, allow the clinician to determine the integrity of various mental processes. Using this information, diag-nostic inferences can be made regarding the presence or absence of brain disease and the potential confounding influences of depression, anxiety and other medical factors. The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of the cognitive domains assessed by a stan-dard neuropsychological evaluation with focused consideration of the domains specifically affected by normal brain ageing, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease and geriatric depression.

PRINCIPAL COGNITIVE DOMAINS IN THE GERIATRIC EVALUATION

When patients present with memory or other cognitive complaints, objective verification of the nature and extent of these problems and the determination of their functional impact are goals of the neuropsychological evaluation. To ascertain this, the evaluation will assess eight major areas of cognitive function along with aspects of mood and personality. The basic areas assessed or ‘cognitive domains’ include: (i) general orientation and alertness, (ii) attention/concentration, (iii) intellect, (iv) memory, (v) language, (vi) executive functions, (vii) visuoperception/spatial judgement, and (viii) sensorimotor control. A brief discussion of each of these domains and the tests commonly used to measure each are described in the sections that follow. More detailed discussion of the range of instruments available to clinicians can be found in other sources3.

General Orientation

Orientation is a particularly important function that can be disrupted by a number of medical (e.g. delirium), psychiatric (e.g. depression) and neurological disorders4. In assessing general personal awareness, the neuropsychologist will establish the patient’s ability to orient to time (e.g. year, date, time of day), place (e.g. current location), personal information (e.g. name, age) and situation (e.g. why they are having a doctor’s appointment). Commonly, the examining clin-ician may use mental status tests in which orientation screening is included, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)5 or more detailed batteries, such as the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale6 and the comprehensive memory battery of the Wechsler Memory Scale7. Targeted, well-validated measures of orientation, such as the Temporal Orientation Test (TOT)8, are often selected and preferred by neuropsychologists over mental status screening tests, in order to streamline the evaluation and allow comprehensive evaluation of domains only cursorily measured in a screening metric.

Attentional Functions

The components of attention tapped within the neuropsychological examination include visual and auditory: (i) simple attention span, (ii) selective attention, (iii) vigilance or sustained attention, (iv) divided attention and (v) alternating attention9. There are a number of well-validated tests from which to choose when assessing attention and concentration, some of which are now computerized.

Simple attention span, the number of units held in immediate mem-ory, is commonly assessed by tests such as the Digit Span subtest from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III (WAIS-III)10 or the Spatial Span test of the Wechsler Memory Scale III7. Selectiveatten-tionrequires the ability to respond to relevant stimuli while simul-taneously inhibiting response to irrelevant, distracting stimuli, such as in speeded target identification tasks (e.g. Symbol Search of the WAIS-III) or the Ruff 2 and 7 Selective Attention Test10,11). Vigilancerequires that stimuli be attended to over a period of time, commonly assessed by computerized continuous performance tests (CPTs), such as the Test of Variables of Attention (T.O.V.A.)12. Dividedattentionrequires response to multiple competing tasks that occur simulta-neously, such as tasks involving the simultaneous performance of both verbal repetition and visual search tasks. Alternatingattentionrequires an individual to shift between tasks, such as the Trails B task, which requires switching between number and letters. It should be noted that tests of attention are easily influenced by a number of factors.

Failure on any single attentional test, or any neuropsychological test for that matter, can occur for a myriad of reasons. Consequently, it is important to consider confounds (e.g. sensory or motor limi-tations) and factors that may modify performance (e.g. educational experience) before drawing conclusions regarding impairments. Typ-ically a neuropsychologist will look for consistency of performance across at least two tests measuring the same cognitive function before drawing an inference of compromised function.

Intelligence

Intelligence is a multifaceted construct that examines capacities of reasoning, problem solving, creative thought and abstraction, measured both verbally and non-verbally. Significant impairments in this domain result in compromised function, a defining feature of dementia. The tests most commonly used for the purpose of assess-ing intelligence are those of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV (WAIS-IV)13 (and its predecessors, WAIS-III and the WAIS-R), due to the well-established psychometric properties (reliability, validity and clinical utility) and extensive normative information for a broad age range (age 16–89). The WAIS tests also afford a comprehensive survey of a number of complex cognitive processes, including calculation, verbal and non-verbal abstraction, fund of knowledge, comprehension, reasoning and problem solving, spatial judgement, and sensorimotor integration. In situations where administration of an entire intelligence battery may be impractical, shorter versions are available (e.g. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, WASI14). Alternatively, the neuropsychologist may sample specific areas of concern. Subtests of the WAIS, such as Block Design and Similarities, are sensitive indicators of brain disease and are often selected to quickly assess non-verbal and verbal abstraction, respectively.

Learning and Memory

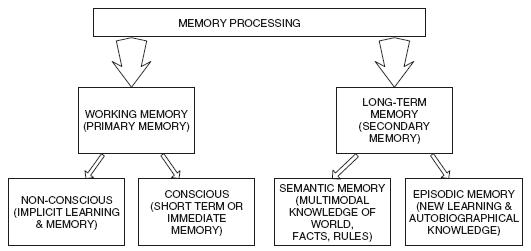

A considerable portion of the neuropsychological evaluation is gen-erally devoted to the in-depth characterization of the different com-ponents involved in the learning and retention of new information as depicted in Figure 62.1. The pattern of deficit across these varying learning and memory processes can suggest one medical condition over another. In a standard neuropsychological evaluation of demen-tia there will be measures of semanticmemory, the recall of well-learned facts and world knowledge, and episodicmemory,the rich person-specific memory that records all new occurring daily events. Tests of semantic memory include category or semantic fluency tests, which require the patient to generate items to a category or group items that are related to one another along specific dimensions (living vs. non-living; instruments vs. tools). Other tests tap recall of world knowledge and are built into larger memory batteries7.

Episodic memory and its component processes of encoding, storing and retrieving new information are determined using tests aimed at verbal and visual learning and memory functions. Acquisition of new information over multiple trials examines the efficacy of encoding whereas assessment of memory retention over short intervals (less than 3 minutes) and extended delay periods (30+minutes) allow inferences regarding consolidation. Recognition memory allows determinations of the integrity of retrieval when cueing is provided.

Tests commonly used to assess memory are summarized in Table 62.1 and include comprehensive batteries such as the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-III)7. Targeted verbal learning and memory measures include the California Verbal Learning Test II15, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised16 andthe ReyAuditory Verbal Learning Test (Rey AVLT)17. Complementary visual memory tests include the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised18 and the Benton Visual Retention Test19. An entire listing of all available memory tests is beyond the scope of this review. However, a summary of commonly used metrics in current practice is presented in Table 62.1, and the reader is referred to other comprehensive sources3.

Figure 62.1 Neuropsychological conceptualization of learning and memory organization. Conscious aspects of working memory that require immediate, short-term processing of information and processes of semantic and episodic memory are typically assessed in the geriatric evalu-ation. Non-conscious learning and memory (e.g. motor memory, habits) are not typically assessed directly in the clinical neuropsychological examination

Table 62.1 Domains and common tests used to measure memory

| Domain | Common tests |

| Orientation | Temporal Orientation Test8 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination5 | |

| Mattis Dementia Rating Scale II6 | |

| Wechsler Memory Scale III7 | |

| Attention | Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III10 |

| Cancellation Tests (Ruff 2&7 test)11 | |

| Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA)12 | |

| Intellect and premorbid function | Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) |

| WAIS-R, WAIS-III, WAIS-IV10,13,31 | |

| Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI)14 | |

| Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) | |

| Memory | Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS): WMS-R, WMS III, WMS-IV7,13,69 |

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test17 | |

| California Verbal Learning Test-II15 | |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised16 | |

| Rey Osterrith Complex Figure Test30 | |

| Brief Visuospatial Memory Test18 | |

| Benton Visual Retention Test – 5th Edition70 | |

| Language | Multilingual Aphasia Examination (MAE)21 |

| Boston Naming Test 2 (BNT2)20 Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination – Third Ed (BDAE-3)20 | |

| Executive function | Wisconsin Card Sort Test (WCST)71 |

| Halstead Category Test72 | |

| Stroop Color-Word Test23 | |

| Trail Making Test A and B | |

| Tests of Verbal and Design Fluency21,73 | |

| Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS)22 | |

| Visuospatial/perceptual | Judgment of Line Orientation Test28 |

| Benton Facial Recogniton Test28 | |

| Hooper Visual Organization Test32 | |

| Clock Drawing Test20 | |

| Sensorimotor | Finger Tapping Test/Finger Oscillation |

| Reitan Battery – Grip Strength | |

| Grooved Pegboard | |

| Purdue Pegboard | |

| Reitan Battery – Tactile Performance Test |

Language

Verbal communication in day-to-day life relies on the individual’s ability to express and comprehend oral and written speech. Formal neuropsychological evaluation focuses on spoken and written expressive language and on comprehension or ‘receptive’ language abilities. The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Exam20 and the Multilin-gual Aphasia Exam21 are two comprehensive batteries of language function commonly used. Administered in their entirety, each aphasia battery takes approximately 30–60 minutes to administer. Unless language disorder is the referral issue, more focused brief testing of specific functions is frequently a preferred approach. Expressive language will be assessed with fluency measures, such as the Controlled Oral Word Association Task (generating words beginning with a specified letter, e.g. ‘R’), and with tests of ‘semantic fluency’ in which participants provide examples to a given category (e.g. sports). The Boston Naming Test, a visual naming procedure, is used to formally assess word-finding difficulty. Impairments in aural and written comprehension, if not detected during the interview, are often assessed with subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, including Comprehension, Vocabulary, Similarities or Information (see section on Intelligence).

Executive Functions

Executive functions, commonly referred to as higher order cognitive functions, comprise a number of supervisory processes that provide some control over many fundamental cognitive abilities and in the organization of general behaviour. The basic components of execu-tive function include planning and organization abilities, monitoring and inhibition of responses, set shifting and cognitive flexibility, and verbal or non-verbal abstract reasoning. Attention and concentration processes, discussed previously, are also subsumed under the broad category of executive control; however, typically, these very specific functions are assessed separately.

There are a number of neuropsychological measures used to tap executive disorders. Comprehensive, all-in-one batteries of executive abilities include the Delis-Kaplan battery, which examines flexible behaviour, problem solving, judgement, personality and abstraction22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree