The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) suggests the terms

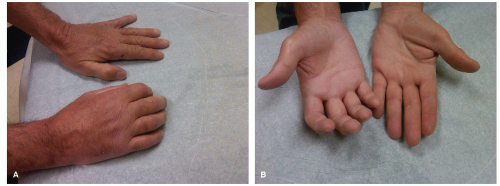

complex regional pain syndrome type I (CRPS type I) for reflex sympathetic dystrophy and CRPS type II for causalgia. The sole differentiating criterion between CRPS type I and type II is the presence of a known nerve injury in CRPS type II. CRPS type I usually follows an initiating noxious event, is not limited to the distribution of a single nerve, and is apparently disproportionate to the inciting event. At some point, there is associated edema, changes in skin blood flow, abnormal sudomotor activity in the region of the pain, allodynia, or hyperalgesia. CRPS type I is associated with a variety of precipitating factors (

Table 51.1); trauma is the most common precipitating event (

Fig. 51.1A and B).

I. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Various hypotheses include peripheral mechanisms, central mechanisms, or psychogenic factors.

A. Peripheral mechanisms do not address the spread of pain beyond a dermatomal terri tory and pain occurring in patients without nerve injury. They are of four types.

1. After an inciting event, a subset of C-polymodal nociceptors develop sensitivity to sympathetic stimulation and thus may be stimulated by noradrenalin. An alternative explanation is that noradrenalin may act indirectly through the release of prostaglandins that stimulate the nociceptors.

2. Sympathetic efferents cause abnormal activation of peripheral nociceptors.

3. Aberrant nerve sprouts generated at the site of injury develop into neuromas.

4. Artificial synapses form at the site of nerve injury and allow “ephaptic” transmission between sympathetic efferent and sensory afferent fibers.

B. Central mechanisms are of two types.

1. Self-sustaining loops of abnormal interneuronal firing in the dorsal horn, after being propagated by a peripheral irritative focus, give rise to ascending projections of pain and descending sympathetic hyperactivity.

2. Long-term sensitization or “wind-up” of wide-dynamic-range neurons in the spinal cord resulting from ongoing nociceptive stimulation from the periphery. The sensitized wide-dynamic-range neurons then respond to activity in large diameter A-mechanoreceptors that are activated by light touch. The pain threshold is reduced and previously subthreshold stimuli are then perceived as painful.

C. Psychogenic factors. A major issue in the diagnosis and management of CRPS is the lack of properly controlled comparison studies of placebo with sympathetic blockade. Furthermore, a fair number of patients with neuropathic pain improve with injec tions of placebo. In some patients, symptoms may be conversion-somatization of an underlying psychiatric condition, because these patients seem to respond to cognitive psychotherapy.