Congenital Intraspinal Cysts

Congenital cystic lesions of the spine are rare entities in children. These developmental lesions are often slow-growing and can present in childhood or early adulthood with a range of symptoms related to nerve root or spinal cord compression. The lesions are readily identified on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. Although they are often identified as isolated lesions, many congenital cysts are associated with various forms of spinal dysraphism and vertebral column abnormalities.

Arachnoid cysts are benign arachnoid diverticula filled with spinal fluid that can occur along the entire neuraxis. Spinal arachnoid cysts occur less frequently than intracranial arachnoid cysts. Little has been reported on the incidence of spinal arachnoid cysts in the general population. A review of children undergoing routine MR imaging of the brain found that intracranial arachnoid cysts were present in 2.6% of the children, but it is presumed that spinal arachnoid cysts occur much less frequently.1 In a retrospective review, 25% of arachnoid cysts that required surgical intervention were intraspinal.2

Neurenteric cysts are endodermal inclusion cysts of the spinal canal. Numerous names have been given to this entity in the literature, and all of them describe cystic structures of endodermal origin. Frequently used names in the literature include neurenteric cyst, archenteric cyst, intestionoma, enterogenous cyst, dorsal enteric fistula, and neurenteric canal remnant.3 For the purposes of this chapter, the term neurenteric cyst will be used.

Spinal dermoid and epidermoid cysts are congenital tumors thought to arise from abnormal rests of ectodermal cells. These lesions can occur in the intraspinal or intracranial space. In a large series published by Lunardi et al, spinal dermoid and epidermoid tumors represented 2.2% of all surgically resected primary spinal tumors.4 The lesions commonly present in early childhood and account for 17% of all primary spinal tumors diagnosed within the first year of life.4 Dermoid tumors are more common in the spine, whereas epidermoid tumors are more commonly cranial in location.

28.1 Arachnoid Cysts

Although intracranial arachnoid cysts are more prevalent in males, a similar distribution has not been found for spinal arachnoid cysts. Spinal arachnoid cysts have on rare occasion been found to be familial.5–7 These lesions have also been reported to be associated with genetic conditions, including hereditary distichiasis, neurocutaneous melanosis,8 and Noonan syndrome.9 Spinal arachnoid cysts are also prevalent in patients with spinal dysraphism, most frequently presenting in those with open neural tube defects or split-cord malformations.10

Arachnoid cysts have been reported in the extradural and intradural space. Rare cases of intramedullary arachnoid cysts have also been reported.11,12 The majority of these cysts are solitary and located within the thoracic spine, although cases of multiple spinal arachnoid cysts have been reported.13 Arachnoid cysts, unlike neurenteric cysts, are more likely to be located dorsal to the spinal cord.

The mechanism that leads to the development of a spinal arachnoid cyst is not entirely known. There are likely multiple causes for these lesions. Intradural arachnoid cysts have been postulated to arise from congenital diverticula of the arachnoid. Extradural arachnoid cysts are thought to arise from the herniation of arachnoid through a weakness in the spinal dura.14 Perret et al suggested that spinal arachnoid cysts are derived from an expansion of the septum posticum, an arachnoid partition dividing the posterior spinal subarachnoid space.15 This theory is supported by the frequent reports of congenital intradural and extradural arachnoid cysts found dorsal to the spinal cord.

Some spinal arachnoid cysts likely arise secondary to inflammation, trauma, or subarachnoid scarring.16–18 Spinal arachnoid cysts in children with myelomengingocele have been postulated to result from extensive subarachnoid scarring and alterations in the flow of spinal fluid, and they may be acquired lesions.10

A number of theories have been proposed to account for the growth and progression of spinal arachnoid cysts. The most common theory states that a ball valve mechanism exists between the cyst and subarachnoid space, allowing the one-way flow of spinal fluid into the arachnoid cyst.19,20 Other investigators have postulated that an osmotic gradient exists between the cyst and extracystic space, or that there is fluid hypersecretion by the cells lining the cyst wall.21

The symptoms related to spinal arachnoid cysts can be nonspecific and subtle. Symptoms are usually the result of compression on the spinal cord or spinal nerve roots. About 50% of children with arachnoid cysts present with pain.23,24 Children often report back pain or radicular arm, thoracic, or leg pain. Other common symptoms include motor weakness, gait instability, sensory disturbances, and urinary incontinence or retention. Symptoms are often aggravated by upright positioning, coughing, and straining as fluid is forced into the arachnoid cyst or intraspinal pressures fluctuate. Children may also present with unexplained scoliosis or kyphosis.24 Physical examination often reveals evidence of a myelopathy or radiculopathy, depending on the location and level of the lesion. Children may also have point tenderness of the midline spine or palpable evidence of scoliosis.

Plain radiographs of the spine may be entirely normal or show subtle evidence of an arachnoid cyst. The presence of kyphoscoliosis may be apparent on radiographs. There may be nonspecific findings of an underlying mass, including scalloping of the vertebral body, thinning of the pedicles, and widening of the interpedicular distance. Computed tomography (CT) after myelography can show evidence of cord compression and the flow of contrast around or into an arachnoid cyst, but this study has largely been supplanted by MR imaging as the diagnostic test of choice.25

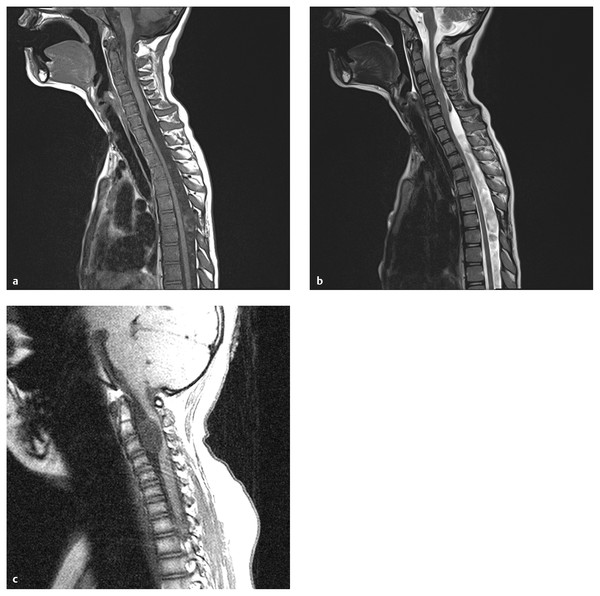

MR imaging reveals a cystic structure with fluid that is isointense to spinal fluid on T1- and T2-weighted images25,26 (▶ Fig. 28.1). Occasionally, increased protein in the cyst will cause a T1-weighted signal slightly higher than that of (▶ Fig. 28.1c). MR imaging has the ability to identify both the lesion and the degree of spinal cord and nerve root compression. The cyst wall usually is smooth and shows no evidence of abnormal contrast enhancement. More recently, cine MR imaging has been used to show abnormal spinal fluid flow at the cyst wall boundary and dynamic cord compression.27

Fig. 28.1 Arachnoid cyst. (a) Arachnoid cysts are typically located dorsal to the cord, like this cervicothoracic lesion, with the cyst fluid slightly hypointense to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on T1-weighted sequences. Mild cord compression is seen. (b) On the T2-weighted sequence, the cyst fluid is hyperintense to CSF, and flow voids can be seen above and below the cyst, helping to define its extent. (c) The surgically proven arachnoid cyst shown is unusual in its location, anterior to the cord, and in its signal characteristics, which are slightly hyperintense to those of CSF. The flow void artifact (bottom of cyst) helps to define the lower cyst margin.

Pathologically, these lesions are composed of a collagenous membrane lined by a flattened meningothelial cell layer. Focal areas of meningothelial cells may be present. Immunohistochemical labeling studies are often unremarkable.28

The treatment of arachnoid cysts can range from simple observation to surgical fenestration or resection, although surgical fenestration or excision of these lesions has been the treatment of choice for many years. Observation may be chosen for those cysts that are discovered incidentally in children without symptoms referable to the cyst.

When surgical treatment is chosen, a posterior approach is usually preferred because the majority of these cysts are dorsal to the spinal cord. Laminoplasty is often performed rather than laminectomy in an attempt to reduce the incidence of postoperative spinal deformity.29 Intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring, including somatosensory evoked potentials and motor evoked potentials to monitor the function of the spinal cord during cyst excision, can also be employed.

For extradural arachnoid cysts, the cyst wall should be present immediately after the laminotomy has been performed. The cyst wall is dissected free of the surrounding tissues, and in most instances a small rent will be visualized along the dorsal surface of the dura. The cyst wall is completely resected, and the dura is closed with sutures. Intradural exploration can be performed if there is concern for intradural extension of the cyst. Rare instances of extradural arachnoid cysts without a clear intradural connection have been reported.30

For intradural arachnoid cysts, the dura is opened and tacked back to expose the cyst. The cyst is carefully removed from the dural surface, spinal cord, and nerve roots under magnified vision (i.e., an operating microscope). When the cyst wall is densely adherent to the spinal cord or nerve roots, those parts of the wall are left behind. For ventral cysts, wide fenestration of the cyst into the subarachnoid space is often performed because it is difficult to access the entire cyst without putting significant traction on the spinal cord.31

Cyst-to-subarachnoid space shunting or cyst-to-pleura shunting is a viable surgical alternative.10 More recently, investigators have utilized intrathecal endoscopy to minimize the incision and bone removal; however, the utility of this approach is unclear.32,33 Percutaneous image-guided aspiration of spinal arachnoid cysts has been reported.34,35

Outcomes of surgical treatment are good. Bond et al recently reported that 87% of patients had symptomatic improvement after surgical fenestration or resection of a spinal arachnoid cyst.11 The recurrence rate of arachnoid cysts treated with excision or wide fenestration is low.11,31 Although short- and intermediate-term results have been good, some studies have suggested late worsening following the treatment of spinal arachnoid cysts.36

28.2 Neurenteric Cysts

Neurenteric cysts are distinctly uncommon, accounting for roughly 1% of spinal neoplasms.37,38 Older retrospective studies have shown a slight male predominance.38,39 However, more recent studies have shown widely varying distributions.37,40–42 Patients can present with symptoms at any time during childhood or early adulthood.

The majority of spinal neurenteric cysts are located in the intradural extramedullary space ventral to the cervical or thoracic spinal cord. This is likely due to their origin from the foregut. Fewer than 5% of reported cases are wholly or partially intramedullary.43 A distinct minority of these lesions have been identified in the lumbar region.44

Although neurenteric cysts can occur in isolation, it is not uncommon for them to occur with other congenital spinal abnormalities. Neurenteric cysts have been found in association with various vertebral column anomalies, including partial sacral agenesis, block vertebrae, hemivertebrae, Klippel-Feil anomaly, and butterfly vertebrae.37,40,44 In addition, syringomyelia, split-cord malformations, spinal cord lipomas, and dermal sinus tracts have been found in association with neurenteric cysts.37,45,46 Although they are generally benign in nature, dissemination and malignant transformation of these lesions have been reported.47,48

The embryologic origin and pathogenesis of spinal neurenteric cysts are not entirely clear. Incomplete separation of the foregut from the notochord during early embryonic development seems to be an integral component in the development of a neurenteric cyst. During the third week of embryonic development, the mesoderm along the midline of the embryo coalesces to form the notochord. Also during the third week, intercalation of the notochord into the endoderm occurs briefly, and a primitive neurenteric canal forms connecting the endoderm and ectoderm through the notochord.49 Neurenteric cysts likely are derived from abnormalities occurring during this early developmental period. Macdonald et al reviewed four theories of neurenteric cyst pathogenesis.49 These theories include splitting of the notochord with an aberrant persistent connection between endoderm and ectoderm, incomplete or abnormal excalation of the notochord, ectopic spinal rests of endoderm, and persistence of the primitive neurenteric canal.

A range of symptoms have been associated with spinal neurenteric cysts. Many present with the same constellation of symptoms seen in children with arachnoid cysts, including back pain, radicular pain, paresthesias, weakness, gait changes, and changes in bowel or bladder function. These symptoms generally result from compression on the neural and vertebral elements. Uncommon presentations of neurenteric cysts include unexplained fever,40 cyst rupture with resultant chemical meningitis and arachnoiditis,50 recurrent bacterial meningitis,51 and intracystic hemorrhage.52

Plain radiographic images are of limited utility in the diagnosis of a neurenteric cyst. However, these studies can be useful in documenting the range of vertebral anomalies that are commonly found in conjunction with these lesions. Holmes et al noted that 77% of children with neurenteric cysts had abnormal plain radiographs.39

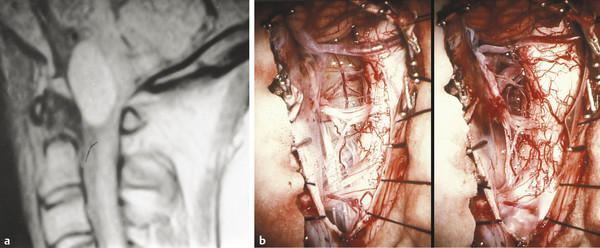

MR imaging is the diagnostic test of choice (▶ Fig. 28.2). The signal characteristics of the cyst fluid are variable and depend largely on the protein content of the cyst fluid.53 In general, the cyst fluid is isointense to slightly hyperintense compared with spinal fluid on T1- and T2-weighted imaging sequences. The cyst itself is often thin-walled and shows no evidence of enhancement. The degree of nerve root and spinal cord compression can also be ascertained from MR imaging.

Fig. 28.2 Neurenteric cyst. (a) The neurenteric cyst in this sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image is typical in location (anterior to the cord) and signal characteristics (slightly hyperintense). (b) Intraoperative view of the anteriorly placed, well-defined neurenteric cyst, surrounded by the vessels and nerves of the upper cervical spine, before and after complete resection.

(From Menezes AH. Tumors of the craniovertebral junction. In: Winn HR, ed. Youmans Neurological Surgery. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; 2011:3114–3130.)

Grossly, these lesions may be thin-walled or thick-walled. The cyst fluid can vary from clear to quite turbid. Light microscopy shows evidence of an epithelial layer, with goblet cells, ciliated cells, and squamous cells lying on a basement membrane. Immunocytochemical studies show cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen positivity in the endothelial cells.49 Although the epithelium is presumed to be of gastric origin, Morita et al, using electron microscopy, found that the features of the epithelium of the wall of a recurrent neurenteric cyst were more consistent with a respiratory origin.54

As for arachnoid cysts, surgical resection is the primary treatment modality for symptomatic neurenteric cysts. However, these lesions are often ventral in location, making surgical access difficult. Total excision of the cyst with decompression of the spinal cord and nerve roots is the goal of surgery. Subtotal resection is often necessary to avoid damage to the spinal cord and nerve roots when the cyst is highly adherent to these structures or when significant manipulation on the cord would be required to fully access an anterior lesion.

Both posterior and anterior approaches to these lesions have been reported. The posterior approach avoids the extensive bone work and fusion that may be required for anterior approaches, but ventrally located cysts are difficult to access or completely resect from a posterior approach. When ventrally located cysts are approached from a posterior laminoplasty, care must be taken to avoid undue traction on the spinal cord and nerve roots.37,40 The dentate ligaments can be sectioned to allow improved access to the ventral cord. Anterior approaches are technically more challenging, require more bone removal, and are likely to destabilize the spine, necessitating a fusion procedure. However, anterior approaches to ventrally located cysts offer more direct visualization and usually allow greater resection of the cyst wall.50,55,56

Outcomes after the surgical resection of neurenteric cysts have been generally good. The majority of patients clinically improve following surgical intervention.37,40 More difficult to assess are the long-term outcomes and incidence of cyst recurrence. Recurrence of neurenteric cysts, especially incompletely resected lesions, has been reported. Chavda et al reported a 37% long-term recurrence rate in eight patients over a 30-year period.57 The lesions were slow to regrow, with recurrences noted 4 to 14 years after the initial surgery. Other authors have found recurrence to be relatively uncommon.39,58

28.3 Dermoid and Epidermoid Cysts

Dermoid and epidermoid tumors of the spine are found most commonly in the lumbar region and are usually intradural and extramedullary. In a series of 62 tumors in the region of the conus medullaris and cauda equina, dermoid and epidermoid tumors represented nearly one-third of the total.59 There are conflicting reports in the literature with regard to the male and female distribution of these lesions; however, the most recent series has shown equivalent rates among males and females.60

Classically, spinal dermoid and epidermoid cysts have been thought to arise from an abnormal inclusion of ectodermal cell rests during closure of the neural tube between the third and the fifth week of gestation. Although there is little scientific evidence, some believe that the timing of the abnormal implantation of ectodermal cells determines whether a dermoid or an epidermoid tumor develops. The implantation of less differentiated ectodermal cells early in fetal life leads to the development of dermoid tumors, whereas the later implantation of ectodermal cells leads to more differentiated epidermoid tumors.60,61

These spinal lesions can be iatrogenic. There is good evidence that the introduction of cutaneous cells during procedures such as lumbar puncture can lead to the development of dermoid tumors.62 The delayed development of dermoid tumors has also been reported in children with myelomeningocele.63,64 Although the dermoid tumors may be due to the inclusion of dermal elements during closure of a myelomeningocele, ventral dermoid tumors remote from the site of myelomeningocele closure in these children are likely the result of congenital rests of ectoderm cells.

Inclusion cysts of the spine are most commonly located in the lumbar region and are generally dorsal intradural and extramedullary lesions. Partially intramedullary or completely intramedullary dermoid tumors have been reported.60,65,66 Many congenital spinal and vertebral anomalies have been reported in association with spinal dermoids and epidermoids. Myelomeningocele, split-cord malformation, syringomyelia, and vertebral column fusion anomalies have been reported with intraspinal inclusion tumors. Dermal sinus tracts are particularly common in children with spinal dermoids.60,67

Children harboring intraspinal dermoid or epidermoid tumors can have a range of symptoms. Many children present with symptoms that mimic the typical manifestations of spinal arachnoid or neurenteric cysts, including back and radicular pain, weakness, sensory disturbance, and bladder dysfunction. Scoliosis and kyphosis can occur in these patients. In patients with an associated dermal sinus tract, the presenting symptoms may be a consequence of local infection of the dermal sinus, frank meningitis, or spinal empyema.68

Although a detailed neurologic examination is warranted to look for evidence of a myelopathy or radiculopathy, examination of the back is also important. Common cutaneous findings on examination of the spine include dimples above the gluteal cleft, dermal sinus tracts, hairy patches, and hemangiomas.

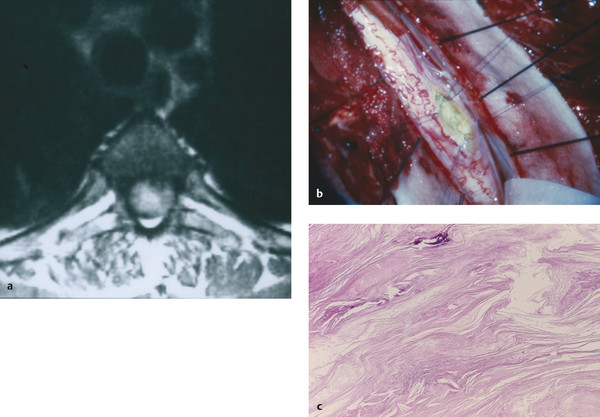

As for other types of spinal cysts, MR imaging is the test of choice for delineating these lesions. Epidermoid tumors tend to have signal characteristics similar to those of spinal fluid, with T1-weighted hypointensity and T2-weighted hyperintensity (▶ Fig. 28.3). Conversely, dermoid tumors often are hyperintense on T1-weighted images and have low signal intensity on T2-weighted images. However, it should be noted that the imaging of dermoid and epidermoid tumors is highly variable.69,70 Diffusion-weighted imaging sequences have shown some early success in distinguishing dermoid and epidermoid cysts from other spinal lesions. Diffusion-weighted imaging sequences often show restricted diffusion in dermoid and epidermoid tumors, whereas arachnoid cysts have no such diffusion restriction.71

Fig. 28.3 Epidermoid cyst. (a) This epidermoid cyst is hyperintense on axial T2-weighted imaging. (b) Intraoperatively, the lesion was found to be intramedullary, located along the posterior–lateral aspect of the spinal cord (pia retracted with Prolene suture). (c) The membrane showed typical stratified, keratinized squamous epithelium.