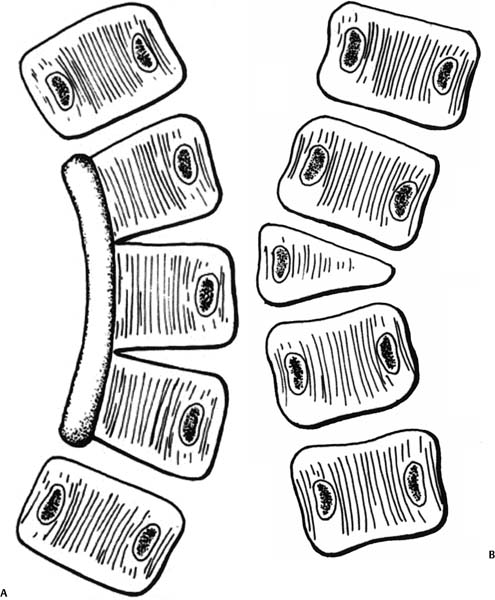

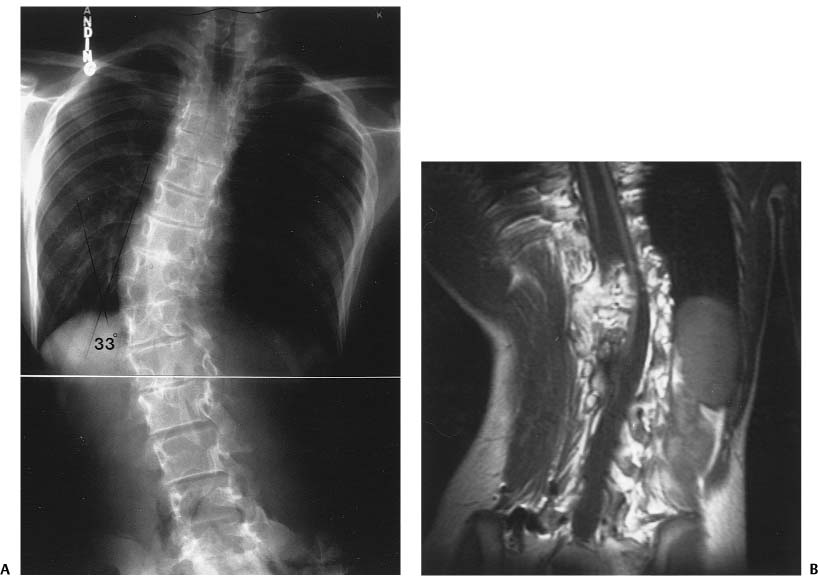

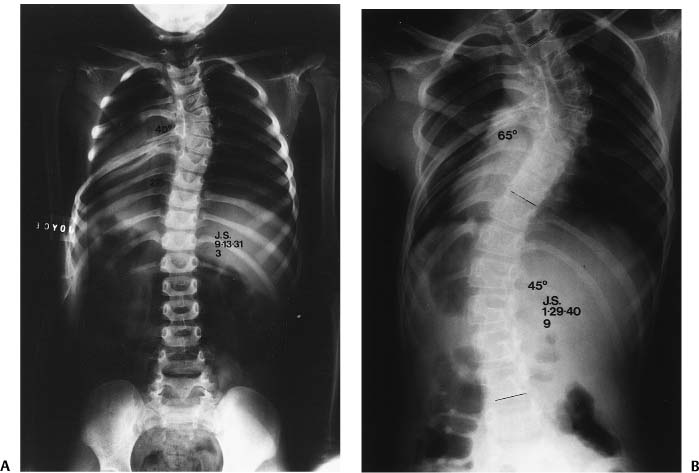

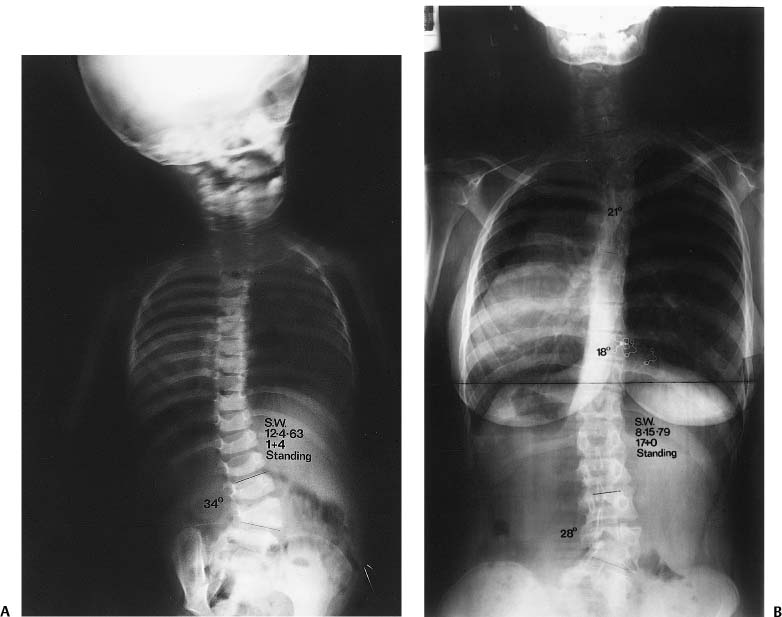

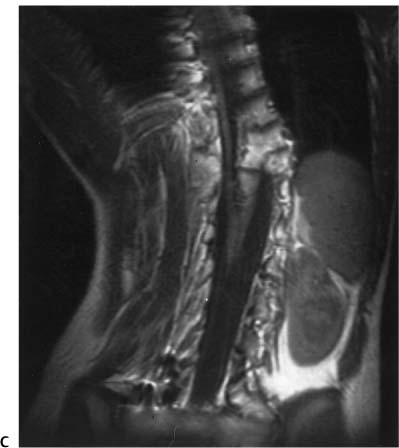

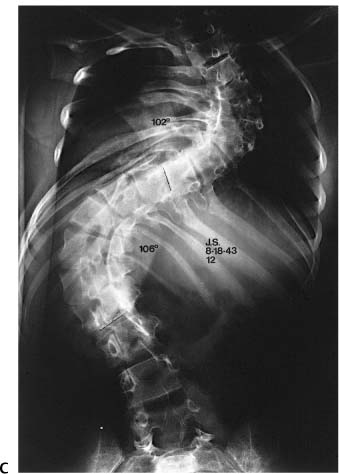

Chapter 12 Congenital scoliosis is, by definition, a lateral curvature of the spine caused by congenitally anomalous development of the vertebrae. These anomalies are present at birth, although the deformity may not show until later in growth. Congenital kyphosis and lordosis can also develop but will not be discussed in this chapter. The anomalies can be failures of formation (i.e., a hemivertebra), failures of segmentation (unilateral unsegmented bar), or mixtures of both. Mixed anomalies are by far the most common. The most common failure of formation is a hemivertebra. These can be single, multiple on the same side, one each on opposite sides at different levels (hemimetameric shift), or “tucked” into the spine without curvature (incarcerated hemivertebra). They can be fully segmented, meaning that there is disk material both above and below the hemivertebra, semisegmented, meaning that there is disk material on one side but not the other, or nonsegmented, meaning there is no disk on either side.1 Defects of segmentation can be symmetrical (total lack of segmentation) creating a bloc vertebra. This does not cause deformity except for lack of motion and vertical growth. Asymmetric defects of segmentation cause deformity. If the bar of nonsegmented bone is lateral, a scoliosis will result. If the bar of bone is anterior, a kyphosis will develop. If posterior, a lordosis will develop. The essence of understanding congenital scoliosis lies in the understanding of the differential in growth of one side of the spine versus the other. If the two sides of the spine are not growing at an equal rate, then deformity will develop. The greater the discrepancy, the more rapid will be the progression and the more severe the deformity (Fig. 12–1). On the whole, congenital scoliosis is not a hereditary problem, but a few exceptions do occur. The main testimony to its nonhereditary nature lies with identical twins. Almost always, if one sib of a pair of identical twins has a congenital scoliosis, the other sib will not have the problem. This author has had the experience of seeing six pairs of identical twins, and in all six pairs, only one sib had the problem. On the other hand, I treated one family that had three children, all three having congenital scoliosis. The parents were not related, did not have scoliosis (both were x-rayed), and a baby daughter of the oldest sib was also free of problems. Scientific studies are few. A review of 1250 patients with congenital spine deformities at our center revealed 12 with a first-or second-degree relative with a congenital spine deformity.2 This was a retrospective study and suffered from a lack of routine radiographs of the relatives. Wynn-Davies of Scotland did a more comprehensive study of the families of 337 patients.3 There are isolated reports of families with multiple individuals with congenital spine deformities, but these appear to be primarily in situations where the parents were closely related. All patients with a congenital spine deformity must have a thorough, total evaluation. The reason for this is not only “good medicine” but also the very high prevalence of anomalies all over the body.4 In the neural axis, these can include hydro-cephalus, Chiari malformation, diastematomyelia, tight filum terminale, lipoma, and syringomyelia. The likelihood of one of these problems is ~40%.5 Abnormalities of the genitourinary system are second in frequency at ~30%.6 Cardiac anomalies are seen in ~20%.5 All sorts of other problems are seen including lung agenesis, limb deficiencies, Sprengel’s deformity, imperforate anus, T-E fistula, and so forth. Figure 12–1 (A) Congenital scoliosis due to a unilateral unsegmented bar. (B) Congenital scoliosis due to a fully segmented hemivertebra. From Winter RB. Congenital Deformities of the Spine. New York: Thieme-Stratton Inc.; 1983. Reprinted by permission. The advent of MRI has allowed for better and safer evaluation of the spine and other structures. The current standard of care is to do MRI in all patients going to surgery for spine deformity, in all patients presenting with a neurologic deficit of any type, and in all patients in whom the routine radiographs suggest an intraspinal anomaly such as a diastematomyelia. Although some physicians advocate an MRI in all congenital spine deformity patients, it is questionable whether the costs and risks of an anesthetic in a small child are justifiable. Needless to say, the responsible physician must do a very careful neurologic examination when the patient is first seen. The kidneys are usually evaluated by ultrasound, but this is not necessary if an MRI is to be done, because the kidneys can be seen well on the MRI. Neither of these tests image the ureters well, and if there is any suspicion of ureteral stenosis (hydronephrosis on MRI or ultrasound), then an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) is appropriate. Clinical evaluation of the spine includes the direction of deformity, length of deformity, rotational prominence, stiffness of deformity, shoulder elevation, lateral decompensation, and sagittal profile. Radiologic evaluation includes standing (if old enough) posteroanterior and lateral full-spine views, supine coned-down view of the deformity area (gives a much better view of the nature of the anomalies than does the long-standing views), and bending, fulcrum, or traction views to determine the curve’s flexibility or rigidity. Further information about details can often be gained from the MRI, especially whether or not segmentation is complete, and whether or not a growth plate is present. CT scans are rarely necessary (Fig. 12–2). The key to understanding the clinical management of patients with congenital scoliosis is to understand the natural history of the various problems. Excellent studies of the natural history are available including Kuhns and Hormel,7 Winter, Moe, and Eilers,8 McMaster,9 and McMaster and Ohtsuka.10 These are fortunately all in agreement and provide a solid base of evidence. Various factors must be taken into account when making an analysis of any given situation. These include the current age of the patient, current state of secondary development, sex, nature of the anomalies, and location of the anomalies. The more years of growth remaining, the more likely is progression. If the pubertal growth spurt is yet to occur, the more likely is progression. If it is a girl, the more likely is progression. If the curve is thoracic or thoracolumbar, the more likely is progression. The most malignant of anomalies is the unilateral unsegmented bar with a contralateral hemivertebra. If located in the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine, there is a progression rate of at least 6 to 10 degrees per year. This means that if a 2-year-old child presents to you with a 40-degree curve, it will be at 100 to 140 degrees by age 12! The second most malignant anomaly is the unilateral unsegmented bar. This will progress at almost the same rate (Fig. 12–3). Hemivertebrae, on the other hand, are extremely difficult to predict. Two adjacent hemivertebrae, both of the fully segmented type, has a very bad prognosis, almost equal to a uni-lateral bar. A single, fully segmented hemivertebra may or may not progress. Only very careful monitoring will give the answer. If it is posterolateral, giving a kyphoscoliosis, the prognosis is much worse. A semisegmented hemivertebra is much less likely to progress, and a nonsegmented hemivertebra almost never progresses (Fig. 12–4). Figure 12–2 (A) A 12-year-old girl who presented with a 33-degree progressive congenital scoliosis due to mixed anomalies (both formation and segmentation defects). (B) A coronal section of her MRI showing a split spinal cord with the two parts passing around a large midline bony mass (diastematomyelia). She was completely normal neurologically. (C) Another “slice” of her MRI showing the left hemicord and the coming together of the two halves to form a normal conus. Periodic observation is one of the most important things we can do. If a patient comes to us with a mild deformity (one not needing immediate brace or surgical treatment), we must follow the patient to determine the evolution of the deformity and its related clinical problems. How often should we see the patient? If in a time of rapid growth (age birth to 4 years and the pubertal growth spurt), the child should be seen every 6 months for both clinical and radiologic evaluation. In the “slow growth” time, visits can be once a year. The neurologic examination should be repeated on each visit, because a child can go from normal to abnormal during that time. Serial photographs can be very helpful, especially for head tilt problems and rib prominence problems. The x-ray should be taken the same way, either standing or supine so that a fair comparison can be made. The x-ray films must be very carefully measured because the congenital spine is not as easy to measure as an idiopathic scoliosis. The physician must always look at the current film, that past visit film, and the original film on every visit. Because there may be only a 6-degree change in a year, that means there will be only a 3-degree change each 6 months, a difference that is easy to overlook. Some surgeons have stated that the measurement accuracy is very poor, but we have found that if great care is taken, the accuracy is equal to that in idiopathic scoliosis.11 Figure 12–3 (A) A 3-year-old girl with a 40-degree congenital scoliosis due to a unilateral unsegmented bar at T3-T6. No treatment was given. (B) The same patient at age 9; the congenital curve now 65 degrees with a thoracolumbar compensatory curve of 45 degrees. (C) By age 12, her congenital curve was 102 degrees and the lower compensatory curve 106 degrees. From Winter RB. Congenital Deformities of the Spine. New York: Thieme-Stratton Inc.; 1983. Reprinted by permission. Figure 12–4 (A) This 1-year-old girl was noted to have a 34-degree lumbar congenital scoliosis due to a semisegmented hemivertebra at L3. Note also the asymmetric development of S1. (B) She was followed without any active treatment. At age 17, the lumbar scoliosis measured 28 degrees. From Winter RB. Congenital Deformities of the Spine. New York: Thieme-Stratton Inc.; 1983. Reprinted by permission.

Congenital Scoliosis

♦ Classification and Terminology

♦ Genetics

♦ Patient Evaluation

♦ Natural History

♦ Nonoperative Treatment

Periodic Observation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree