INTRODUCTION

Depression is the most common mental disorder in later life, affecting up to 15% of those over 651. Studies focused on the needs of people from minority ethnic groups suggest at least the same high prevalence of depression among south Asian and black Caribbean groups in the UK2 . It has been suggested that ethnic elders may be more vulnerable to mental illness than the majority population and the term ‘triple jeopardy’ has been used to describe the combined challenge of racism, ageism and socioeconomic deprivation faced by older people from minority backgrounds3. Census data reveal that the proportion of black and minority ethnic individuals over the age of 65 increased from 3% in 1991, to over 8% in 2001. Therefore, it appears inevitable that the prevalence of depression in minority ethnic groups, and the challenges that this presents to health and social services in the UK will rise2. It is also of concern that older adults from minority ethnic groups appear to have lower levels of service use compared with the majority population4.

There are major discontinuities in the management of depression in old age throughout the health and social care system. It is estimated that only 15% of older people with depression receive appropriate treatment from primary or secondary care services5. This may be a function of the inherent complexities of the illness with the presentation of depression anything but uniform. From a cross-cultural perspective, there are suggestions that Asian and black Caribbean patients have their psychological problems identified less frequently than their white counterparts6. Again, this may in part be explained by the variable ways in which depression is manifested and reported by different ethnic groups7‘8. The National Service Framework for Older People has explicitly acknowledged that depression is under- treated in older people, and a key aim is to ensure the early recognition and effective management of depression across ethnic groups9.

BARRIERS ON THE PATHWAY TO CARE

Suggestions of unmet need among ethnic elders10 require an exploration of the potential barriers and facilitators to service use. Goldberg and Huxley (1980) described a succession of filters in the ‘pathway to care’ that determine whether people access mental health services11. Sufferers Beliefs about the nature of the condition, and what is appropriate help, may act as barriers at each of these stages, influencing whether and from whom to seek help, the idioms for expressing the condition, and the acceptability of various treatments12. At present, much of our data on these issues has been derived from studies focused on the needs of working-age adults13,14; among older adult research very few studies have examined the experience of depression across ethnic groups. In the United Kingdom, as in most health-care systems, general practitioners (GPs) are the first point of access to health care, directly providing most of the treatment for common mental disorders as well as referral to specialist mental health services. The beliefs of primary care professionals may represent a further barrier in the pathway to care influencing the recognition and management of depression in older patients7. Thus, it is important to consider whether the large discrepancies between prevalence, identification and treatment of depression is to be found in the attitudes and behaviour of GPs, their older patients or some combination between the two.

Levkoff and colleagues (1988) hypothesized that the most common reason for older people not to seek help from their GP was that they tended to ‘normalize’ symptoms of depression and attribute their condition to the ageing process rather than to disease12. Attributions of the causes of depression have been found to vary between different ethnic groups14. Bhugra (1996) found that south Asian women of all ages had a clear understanding of psychosocial aspects of depression but were not predisposed towards medical models or explanations15. Abas (1996) suggested that older Caribbean people construe mental disorders as secondary to other unmet needs (e.g. physical, social, spiritual)16. There is also evidence that south Asian and black Caribbean adults may favour self-help strategies for depression rather than seeking professional help14. Religious practices (e.g. prayer) have been identified as important ways of coping among minority ethnic groups living in the UK and traditional healers or religious leaders could be considered by these individuals to be a more appropriate and acceptable source of help than Western models of psychiatric care17. Alternatively, talking to friends and family may represent the first line of treatment18. Certainly, research suggests that south Asian and black Caribbean adults do not always envisage primary care consultations as an appropriate response to depression13,19. Negative attitudes towards antidepressants and mental health services in general, may discourage help seeking within minority ethnic groups20.

Yet depression is also under-recognized and poorly managed in primary care5. It appears that the stigma of mental disorder is keenly felt by older adults and feelings of shame have been cited to explain underreporting of affective symptoms by older patients28. Research has pointed to even higher levels of stigma surrounding depression within minority ethnic groups17‘19. There is evidence that GPs construe presentations by south Asian patients as being dominated by physical rather than psychological complaints7. Odell et al. (1997) speculated that a tendency in south Asians to somatise their psychological distress might contribute to low detection rates8. However, Bhui and colleagues (2001) commented that the frequent use by GPs of ‘somatic’ and ‘sub-clinical’ labels in relation to Punjabi patients suggests that although they did not perceive there to be ‘significant psychiatric disorders’ they were aware of some emotional disturbance1. Comino et al. (2001) reported substantial under- detection of depression by GPs among south Asian patients, though the patients were able to identify common symptoms of anxiety and depression themselves2. However, there is accumulating evidence to suggest that the language used to express psychological distress is culturally informed15‘16‘21. Again it is important to emphasize that very few data deal specifically with older people with depression from minority ethnic groups. In order to generate services that are accessible and acceptable to older adults across ethnic groups, service providers need to understand the beliefs that underlie help-seeking behaviour and the likelihood of help being offered and accepted.

A CROSS-CULTURAL QUALTATIVE STUDY OF THE BARRIERS AND FACILITATORS TO CARE

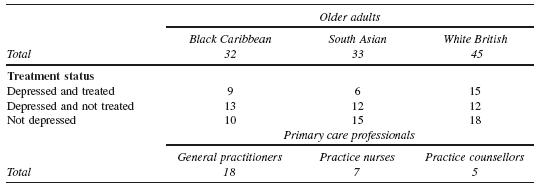

In the light of the gaps in the evidence base identified above, we completed a programme of work to investigate the attitudes, experiences and beliefs of older adults from the three largest ethnic groups in the UK and primary care professionals concerning depression22-24. In-depth interviews were conducted with 110 older adults and 30 primary care professionals (see Table 83.1).

The data incorporates the perspective of older adults with depression (both treated and untreated) and the general older population. Each group included black Caribbean, south Asian and white British older adults; this enabled us to compare and contrast attitudes among the two largest minority ethnic groups in the UK with the majority population. A ‘case’ of depression was defined as a score of 7 or above on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)25. Treatment was not limited a priori to pharmacological interventions (i.e. antidepressants) but in the event no participants were receiving psychological treatments alone. We identified participants through seven primary care practices and through day centres and lunch clubs serving the black Caribbean, south Asian and white British communities. Topics for the interview guide were generated from the research literature. We used a vignette describing an older person with symptoms typical of depression as a starting point to enable us to explore the idioms used to express mental distress and attitudes toward mental illness in our sample18‘19‘21. Interviews then explored: what the word depression meant to participants; what participants thought might cause depression; what someone with depression should do’ what help might someone with depression need; who should help them and how. The older adults were then asked to give their opinions on a range of treatments and services. Information sheets’ consent forms’ the HADS and the vignette were available in four Asian languages: Gujarati’ Hindi’ Punjabi and Urdu. Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes’ unless they stated a preference to be seen elsewhere’ lasted around one hour and were conducted in the participants’ preferred language. All were recorded on audio-tape and transcribed verbatim.

In-depth individual interviews were conducted with GPs’ practice nurses and practice counsellors working in 18 primary care centres in south London. The sample was selected purposively to include professionals working in different settings (single-handed and group practices)’ serving areas of contrasting socioeconomic and ethnic characteristics. One-third of the participants were recruited from primary care research networks’ and two-thirds were selected from information published on local primary care trust websites. Key topics explored in the interviews included: perceptions of the experience and presentation of depression in older people; perceptions of older people’s beliefs about depression; cultural differences in the above. Analysis of the data was based on the grounded theory approach26. Three members of the research team scrutinized and coded the initial transcripts. Emerging themes were identified and labelled with codes. A constant comparison technique was used to delineate the properties of the codes and to develop categories and subcategories. As the analysis proceeded’ we verified and developed existing codes and added new codes where necessary. The researchers compared their coding strategies and any instances of disagreement were discussed and resolved by the wider research team. NVivo qualitative data analysis software was used to process the transcripts. The number of interviews completed in each group was determined by ‘saturation of data’, i.e. the point at which no new themes emerged from the interviews.

The themes to be presented in this chapter emerged from the analysis of: firstly, older adults’ perception of the concepts and causation of depression; secondly, older adults’ attitudes towards help seeking for depression; and thirdly, primary care professionals’ perceptions of the experience and presentation of depression across ethnic groups. The data will be considered in relation to the existing literature.

Older Adults’ Concepts and Causation of Depression

The older adults in our study felt that the ageing process had a considerable number of physical, circumstantial and emotional implications that contributed to depression. It has been suggested that there is a propensity among the elderly to ‘explain away’ depression as a normal part of ageing and that this prevents them seeking help for the condition12. However, in our study, an acceptance of the social and ageing precipitants of depression was not incompatible with the concept of depression as an illness. Roughly three-quarters of the black Caribbean elders and two-thirds of the white British participants defined depression in this way. Assigning the label ‘illness’ appeared to validate and legitimize the experience. Almost half of the white British and black Caribbean participants also viewed depression as a serious condition that was distinct from sadness and grief. Thus, depression was concurrently viewed by these groups as being an understandable, yet dysfunctional, consequence of old age.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree