11 Decompressive Surgery for Herniated Nucleus Pulposus (Open, Micro, and Minimally Invasive Approaches) Christian M. DuBois, Frank M. Phillips and Kevin T. Foley Surgery to treat a symptomatic herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) remains a frequent operation with improvement in symptoms in most patients. The surgery has gone through technical modifications since its introduction in the early 20th century; however, the primary goal remains the same. This principle is to decompress the affected nerve root by removing the HNP with the least damage to the surrounding structures. Walter Dandy’s report of two patients with cauda equina syndrome associated with rupture of intervertebral disc (IVD) in 1929 may have been the first to successfully identify and surgically treat a ruptured IVD.1 However, it is Mixter and Barr’s 1934 article in the New England Journal of Medicine that is widely accepted as the original report popularizing surgical cure for sciatica related to IVD disease.2 Initial enthusiasm for discectomy was tempered by reports of negative explorations and patients suffering from persistent postoperative back pain. Despite the lack of contemporary medical technologies such as microscopes and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the forefathers of disc operations persevered and performed “open” discectomies with good results. Four decades later, Caspar3 and Yarsagil4 reported on the routine use of the microscope to perform lumbar discectomy. The era of “microdiscectomy” was born, emphasizing minimal soft tissue trauma while the microscope improved lighting and visualization. In 1997, Foley and Smith5 reported a “microendoscopic” technique for discectomy using a sequential tube dilating system in combination with an endoscope. The visual limitations of the two-dimensional (2D) working environment encountered with an endoscope proved to be challenging. This prompted the development of a tubular dilation system that could be used with standard three-dimensional visualization techniques, either the operating microscope or loupe magnification. Surgical indications for treating sciatica associated with herniated IVD are controversial at best, particularly since the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) study was published.6,7 In the study, nonoperative patients fared as well as the surgical patients at long-term follow-up, although the more immediate pain relief provided with surgery did have a positive socioeconomic impact. Unfortunately, there were a significant number of patients that crossed over between their assigned operative or nonoperative group, and the use of the “intent to treat” analysis makes it difficult to provide absolute conclusions to support either nonoperative or operative treatment.8,9 Nevertheless, lumbar discectomy remains the most frequent spinal procedure in the United States. Despite the controversy, absolute indications for surgery do exist. Patients demonstrating a progressive neurologic deficit or the development of cauda equina syndrome should be treated with urgent surgical decompression. Patients who experience radicular pain with corresponding radiologic evidence of disc herniation, and who have failed at least 6 weeks of appropriate conservative therapy would also be considered surgical candidates. Other relative indications for surgery would include intractable sciatica or a static motor deficit with positive nerve root tension signs. As for all surgical procedures, proper patient selection is critical for a successful outcome. Most patients will not meet the absolute criteria discussed. As in every medical decision, the patient should be involved in the decisionmaking process. The final decision to proceed with surgery should be made only after a patient has had a thorough discussion with the surgeon regarding the risks and benefits of both nonoperative and operative options. Traditionally, “open” discectomy implied that the surgeons completed a hemilaminotomy through large skin and fascial incisions to access the disc space without magnification. The contemporary open discectomy is typically now performed using magnification with either loupes or microscopes emphasizing microsurgical techniques. The incision is minimized, and an intraoperative x-ray study is introduced early on to locate and verify the correct operative level. A study by Katayama and colleagues10 prospectively compared the clinical outcomes between traditional open discectomy and microdiscectomy and demonstrated that the outcomes are similar, with microdiscectomy’s having a slight benefit in regard to bleeding and hospital stay. Current minimally invasive discectomy techniques imply the use of a specialized retractor system, which minimizes adjacent soft tissue trauma combined with some form of illumination and magnification. Positioning a patient for lumbar discectomy starts by relieving pressure off the abdominal contents, including the great vessels, to minimize venous bleeding during the dissection. There are a variety of tables and frames available on the market for this purpose (Fig. 11.1). In general, a patient is placed in prone position with knees in a flexed, kneeling position. After ensuring that all pressure points are padded properly, the skin is then prepped and draped in the standard fashion. A spinal needle is then advanced through the skin toward the interspinous process space, and a radiograph is taken to confirm the correct operative level. With the open technique, a small skin incision over the spinous process is made and subperiosteal dissection is performed unilaterally to detach the muscle off the lamina on the affected side. Another radiograph is taken at this point to confirm the operative level. Using loupe or microscopic magnification, the bony and soft tissue landmarks of the lamina and ligamentum flavum are then identified (Fig. 11.2A). The ligamentum flavum can then be safely separated from the undersurface of the more cephalad lamina using a small curette. Fig. 11.1 Jackson frame for the proper positioning of a patient for lumbar discectomy. In cases with a wide enough interlaminar window, the removal of the ligament will provide an adequate working channel to access the disc space to remove the HNP without any bony resection. However, it is usually necessary to perform some degree of laminotomy with limited medial facetectomy to adequately expose the lateral aspect of the nerve root (Fig. 11.2B). This is typically performed using rongeurs and Kerrison punches; however, a high-speed burr may be used in the case of a thickened lamina. The nerve root can be safely retracted toward the midline using a nerve root retractor (Fig. 11.2C). It is particularly important to ensure that the entire lateral edge of the nerve root is visualized and that the nerve root and the ventral surface of the thecal sac are free of any adhesions to underlying tissue. Failure to do so may result in an inadvertent durotomy. With safe and gentle retraction medially, the anulus or herniated fragment will be visualized. There are cases in which large disc fragments may exert dorsal pressure, effectively thinning the nerve roots, which can then mimic the appearance of the anulus. It is imperative that proper identification and differentiation of both the nerve root sleeve and the anulus or disc fragment are performed prior to proceeding with the procedure. After proper identification, the nerve root can be safely retracted and held in place, while the anulus is incised or the extruded fragment is removed (Fig. 11.2D). In general, it is safer to make the initial cut into the disc space along the longitudinal direction of the nerve root as this will minimize the risk of potentially cutting the nerve root. Prolonged retraction of the nerve root should be avoided to prevent iatrogenic traction injury, and retraction should be released frequently during the procedure. Once the disc space is incised, herniated material can be removed with the assistance of a ball-tipped probe and pituitary rongeur. If a pituitary rongeur is used, it should not be placed into the disc space any deeper than its jaws to decrease the risk of iatrogenic injury to the great vessels anterior to the spine. Fig. 11.2 Minimally invasive microdiscectomy technique. HNP, herniated nucleus pulposus; ENR exiting nerve root; LF, ligamentum flavum; IF, inferior facet; SF, superior facet. There are two schools of thought on the amount of disc material removed during a discectomy. Some surgeons favor removing a generous amount of disc from the intervertebral space. This is thought to reduce the rate of reherniation at the same operative site. Some hypothesize that the decreased disc height contributes negatively and causes spondylosis and possible failed-back syndrome. With this in mind, other surgeons aim to minimize the amount of disc material removed during surgery and only remove the offending disc material. Recent data would seem to support the latter.11,12 Barth and colleagues reported on 84 patients who were randomized to either sequestrectomy or traditional microdiscectomy and followed prospectively for 2 years. The technique for those patients who underwent sequestrectomy allowed removal of the offending disc fragment without entering the disc space. Discectomy in those patients in the traditional group involved placing a pituitary rongeur into the disc space “in an attempt to remove as much of the loose intradiscal tissue as possible.” Reherniation rates and objective symptoms of neurologic compression were similar between the two groups. However, functional outcome at 2 years postoperatively was worse among those who underwent a traditional microdiscectomy. In addition, radiographic evidence of postoperative disc degeneration such as loss of disc space height, and Modic endplate changes were less pronounced in the sequestrectomy group. The authors postulate that this may “avert the development of postoperative low back pain.”11,12 These current findings would seem to confirm the findings of Hanley and Shapiro, who postulated that limiting the excision of disc material decreases the incidence of postoperative low back pain.13 The major advantage of a minimally invasive approach is to limit the damage to the surrounding soft tissue while accessing the disc space (Fig. 11.3).14–16 Muscle is not devascularized nor is it under high-pressure retraction during the case. The common pathway to perform minimally invasive discectomy is via a muscle-splitting technique. The natural tissue plane between the sacrospinalis muscle medially and the longissimus and iliocostalis muscle laterally is typically utilized for access. Once a patient is prepped and draped for the surgery, the midline is marked either by a palpation or under C-arm fluoroscopy. A paramedian incision 1.5 cm off the midline is then made for the initial skin incision. The usual length of the incision is —1.5 cm. There is not a routine need for separate incision on the fascia. A Kirschner wire is then advanced through the fascia and toward the bony spine. The smallest dilator is passed over the Kirschner wire through the fascia, and the wire is removed. Using the smaller dilators, most of the muscle can be stripped off the lamina using a small, circular motion (Fig. 11.4). This maneuver will minimize the amount of soft tissue removed to expose the lamina. A 16- to 22-mm diameter tube is routinely used at the appropriate depth for each patient and is positioned over the interlaminar space (Fig. 11.5). Bayoneted instruments are utilized to perform the procedure via the tube. Once the exposure is done and tubes are in place, the rest of the procedure utilizes the same technique as a routine microdiscectomy.

Historical Perspective

Relative and Absolute Indications

Surgical Approaches

Open Discectomy and Microdiscectomy

History

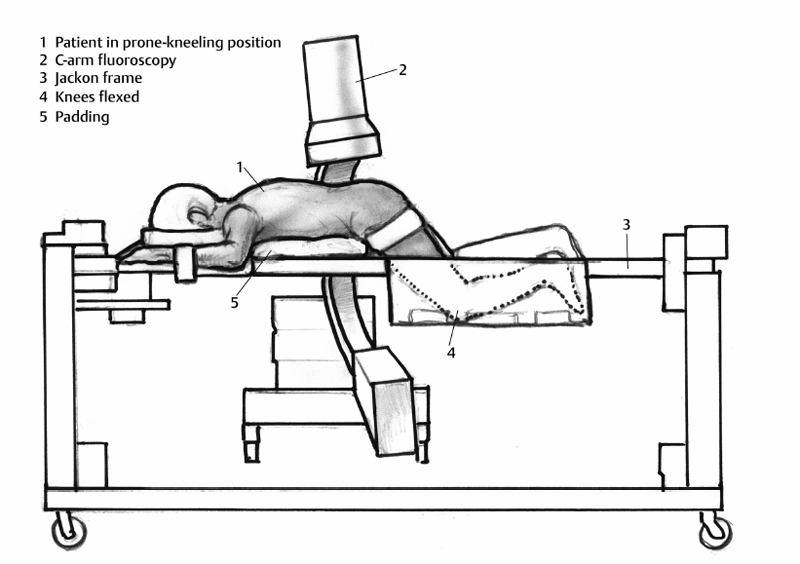

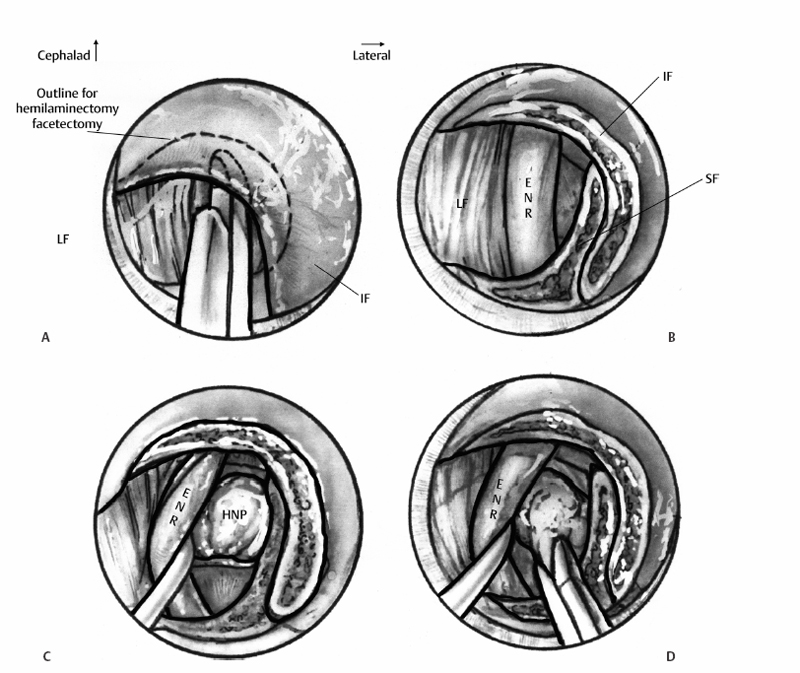

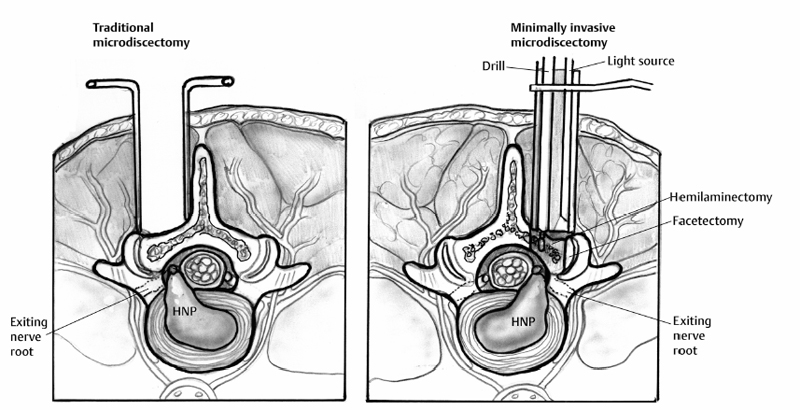

Positioning and Technique

Minimally Invasive Discectomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree