science revisited

mechanisms linked to the development of diabetic polyneuropathy

- Excessive flux of polyols (sugar alcohols) such as sorbitol, which alter Schwann cell and neuronal function

- Disease of small blood vessels (microangiopathy) involving peripheral nerves and ganglia with ischemia and hypoxia

- Damage from free radicals generated by oxidative and nitrative stress

- Insufficient support of neurons because of abnormal levels of neurotropic growth factors or their receptors

- Damage to key neuronal proteins by excessive glycosylation

- Damage from circulating advanced end-products of glycosylation (AGEs) that act on AGE receptors (RAGE) of neurons

- Failure by insulin to offer direct support to neurons through neuronal insulin receptors (with insulin resistance of neurons)

- Combinations of the above mechanisms

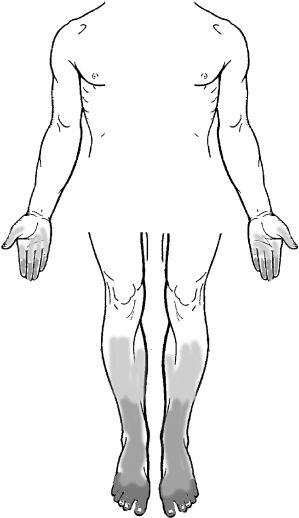

DPN is termed “length dependent” because the distal ends of the longest peripheral axons are involved first. As a result, sensory symptoms and signs first appear in the ends of the toes. As DPN progresses, a pattern of “glove -and-stocking” sensory loss evolves (Figure 22.1). It occasionally involves the center of the chest, the terminal innervation zones of the intercostal nerves. Sensory abnormalities may start in the tips of the fingers somewhat later than in the lower limb. If only some fingers are involved, a superimposed entrapment neuropathy should be suspected such as carpal tunnel syndrome (e.g. involvement of thumb, index, middle, and lateral ring fingers) or ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (e.g. small finger, medial ring finger).

Figure 22.1. Stocking-and-glove abnormalities are the hallmark of diabetic polyneuropathy. The changes indicated may include loss of sensation, paraesthesiae, or pain.

(Modified from Zochodne et al. Diabetic Neurology New York: Informa, 2010.)

Subclassifications of DPN have been proposed based on the involvement of small sensory axons (small fiber), large sensory axons (large fiber), or the presence of accompanying motor involvement. In small-fiber neuropathy, there may be prominent pain, loss of sensation to pinprick and thermal stimulation with preserved sensation to vibration, position, and preserved ankle reflexes. In selective large-fiber neuropathy, a less common phenotype, there is gait unsteadiness, a Romberg sign, loss of sensation to vibration and light touch with relative preservation of pinprick and thermal sensation. Selective motor involvement is rare to nonexistent in DPN and should raise suspicion of another cause of polyneuropathy. In practice, most patients with DPN have a mixture of small- and large-fiber sensory involvement including cases of painful polyneuropathy. Motor involvement tends to occur later during the course of the neuropathy with wasting of intrinsic foot muscles, and later weakness of toe and foot dorsiflexion. Prominent or asymmetric upper limb motor involvement should raise suspicion of a superimposed entrapment neuropathy such as carpal tunnel syndrome or ulnar neuropathy at the elbow.

A comprehensive clinical neurological examination is essential for the bedside evaluation of DPN. This should include assessment of distal motor muscle function, recognition of early wasting, examination of deep tendon reflexes and evaluation of sensory modalities including light touch, pinprick, thermal sensation, vibration perception. and position sensibility. The extent of sensory loss should be documented by establishing whether the patient (with eyes closed) can identify any light touch on the toe (anesthesia) or can distinguish the sharp from the dull end of a clean (not reused) safety pin (analgesia). The proximal extent of this loss should then be mapped. The gait should be assessed for antalgia (difficulty walking secondary to pain) or ataxia (loss of balance). It is important to evaluate lower limb pulses, and to check for foot ulceration. The general physical examination should include evaluation for thyroid enlargement, retinopathy, and carotid bruits. The addition of the Semmes–Weinstein monofilament testing is recommended as a predictor of later foot ulceration. This simple test involves applying a filament of bending force 10 g over the toe. Various scoring methods are described but a standard approach is to ask the patient (with eyes closed) how many times he or she can feel the monofilament pressed over the dorsum of the large toe; five trials should be attempted.

Grading scales for the severity of DPN have been generated, largely for use in research trials.

Focal Neuropathies

Focal neuropathies involving either single peripheral nerves or several adjacent nerves are common in patients with diabetes. Many develop in patients with only mild or recent-onset diabetes mellitus.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

CTS is the most common entrapment in patients with diabetes and can be a source of considerable pain and disability. Female sex, repetitive hand use, previous wrist fractures, and other conditions such as hypothyroidism and connective tissue disorders are risk factors. Its symptoms are acral (finger tip) paraesthesiae as well as pain and sensory loss, with loss of hand dexterity and weakness. Early CTS may present with sensory symptoms only. Patients may awaken with pain or tingling at night or in the morning. More advanced CTS may present with thenar muscle weakness and wasting. Surgical decompression of the median nerve at the wrist benefits CTS patients with or without diabetes.

Ulnar Neuropathy at the Elbow

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow (UNE) develops in approximately 2% of patients with diabetes. Its symptoms are tingling and numbness in the small finger and medial half of the ring finger, with weakness of intrinsic hand muscles. There may be pain in the elbow and hand. In some patients, considerable disability may result. The role of decompression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow, although widely used, remains controversial. Its specific benefits in diabetes mellitus are uncertain. A “Heelbo” pad, a padded arm sock fitted over the elbow, protects the nerve and may improve ulnar neuropathy during its early stages before significant axonal degeneration ensues.

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Entrapment Neuropathy (Meralgia Paresthetica)

This develops from compression at the level of the inguinal ligament. Obesity, pregnancy, recent weight gain, inguinal nodes or scarring, and tight-fitting garments or belts may predispose to its development. The symptoms are tingling, numbness, and pain along the lateral thigh in the distribution of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Preserved reflexes and quadriceps power distinguish this condition from femoral neuropathy, lumbosacral plexopathy, or radiculopathy. The role of decompression is not established in mild neuropathy but appears helpful to patients with intractable neuropathy.

It is unclear whether other forms of compression or entrapment neuropathy are more common in patients with diabetes mellitus. There are, however, other forms of focal neuropathy that are found in patients with diabetes including lumbosacral plexopathy, oculomotor palsy, thoracic intercostal and abdominal radicular neuropathies, and Bell’s palsy (not discussed here).

Lumbosacral Plexopathy

Lumbosacral plexopathy (DLSP; also known as lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy, Bruns–Garland syndrome, proximal diabetic neuropathy, and diabetic amyotrophy) is a subacute motor disorder that develops in older patients, usually those with DM type 2. It presents with deep aching thigh pain, followed by weakness and wasting in the anterior thigh muscles, and occasionally involves adjacent groups of anterior compartment muscles below the knee. The quadriceps reflex disappears but sensory involvement is typically spared. Profound weight loss may accompany the disorder. Some varieties with bilateral symmetric involvement are described but usually the onset is unilateral with some patients developing contralateral involvement over time.

The course is usually protracted with a gradual decline over weeks to months followed by spontaneous recovery. The pain from DLSP can be intense, sometimes requiring opioids and hospitalization, and is described as deep, boring, and aching. No therapy has been identified to shorten the course of this condition; immunotherapy is of questionable benefit. A preliminary study has shown improvement in pain symptoms from a course of glucocorticoid therapy. DLSP may develop in patients with relatively mild DM and sometimes has followed the initiation of insulin therapy. Other causes of lumbosacral plexus damage should be routinely sought using imaging (magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography) of the pelvis and lumbosacral spine. The etiology of DLSP is unknown, although inflammation from microvasculitis and ischemia has been considered.

Thoracic Intercostal and Abdominal Radicular (Truncal) Neuropathies

These present with subacute abdominal wall or thoracic pain resembling that of herpes zoster. They may span more than one adjacent segmental territory and occasionally are bilateral. Loss of sensation to light touch and pinprick can be documented and there may be localized weakness from denervation of muscle segments, e.g. asking a patient to sit from a supine position may demonstrate bulging of a weak segment of abdominal muscle. The pain may be intense, and variously described as tingling, pricking, lancinating, aching at night, with radiation around the chest or abdomen, causing a constricting feeling. The cause of diabetic truncal radiculopathies is unknown. Slow spontaneous recovery usually occurs.

Isolated cranial nerve palsies including pupillary-sparing oculomotor palsy, and trochlear and abducens nerve palsies also occur in patients with diabetes. Imaging, including noninvasive vascular imaging, may be required to rule out a compressive lesion in all three conditions.

Diagnostic Approaches

Electrophysiological Studies

Electrophysiological studies are not required in all patients with diabetes and neuropathic symptoms. They are helpful however, in the presence of atypical features such as subacute progression or prominent motor involvement, especially in the setting of mild DM. Nerve conduction studies first identify declines in the amplitude of the sural sensory nerve action potential (SNAP), then sural sensory conduction velocity, and finally peroneal motor conduction slowing. Widespread loss of SNAPs with diffuse mild-to-moderate conduction velocity slowing, loss of compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs), and distal denervation by needle electromyography (EMG) develop in severe or progressive polyneuropathy. Thus, although some features of primary demyelination may occur in DPN, widespread conduction block, dispersion, or severe slowing of conduction velocity (e.g. <35 m/s in the median forearm motor nerve) are unusual and may suggest superimposed chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP).

Quantitative Sensory Testing

There are several approaches currently available for computerized testing of sensory function in the distal extremities of patients with diabetes. Examples typically include calibrated electronic interfaces for thermal thresholds (warm, cold), heat as pain, touch pressure, and vibration. The thresholds in the feet are raised in DPN.

Autonomic Testing

A large number of specific autonomic tests are now available for testing cardiovascular status, erectile function, sudomotor function (sweating), gastrointestinal motility, bladder function, and pupillary responses. Several of these tests, such as sudomotor testing, are particularly useful in addressing small-fiber function in diabetes. The assessment of small axons in DM is not adequately addressed by nerve conduction studies. The reader is directed elsewhere for more detailed reviews of autonomic testing.

Pathological Studies

Sural nerve biopsy is not recommended for routine clinical use. It is helpful, however, for the diagnosis of unusual or progressive neuropathies in the setting of DM to identify alternate causes such as vasculitis or amyloidosis. In diabetic lumbosacral plexopathy, biopsies of femoral cutaneous branches or the sural nerve have identified inflammation suggestive of vasculitis. The usefulness of this finding to prompt specific vasculitis therapy is uncertain. Skin biopsy, taken either by punch or blister, is a more recent form of evaluation. In diabetes, loss of epidermal axons, retraction endbulbs, and abnormal epidermal fiber length are all described. Determination of skin epidermal fiber density is useful for confirming the presence of small-fiber sensory neuropathies when routine nerve conductions are normal. A noninvasive approach toward the study of small axons in diabetes may be the use of corneal confocal microscopy, a rapid technique that identifies sensory nerve axons in Bowman’s layer of the cornea.

Other

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein is often elevated in DPN but pleocytosis (the presence of white blood cells in CSF) is not expected. Biomarkers of oxidative stress in human diabetes are not specifically recognized as robust diagnostic tools for DPN.

tips and tricks

tips and tricks

- Early DPN may have minimal clinical signs despite the presence of neuropathic pain.

- Many patients with DM may have signs of neuropathy despite being asymptomatic.

- A full neurological examination is warranted including a Semmes–Weinstein monofilament test of mechanical sensation.

- Loss of an ipsilateral knee reflex is an important sign of diabetic lumbosacral plexopathy.

- Diabetic oculomotor palsy usually spares the pupil.

- Painful sensory neuropathy can develop in patients with glucose intolerance without frank diabetes mellitus.