The Regulatory Requirements

The first seizure-related car crash was reported near the turn of the 19th century. Since then, regulatory authorities have placed restrictions on driving for a person with epilepsy. In the early 1990s, the American Academy of Neurology, the American Epilepsy Society, and the Epilepsy Foundation of America convened a conference of thought leaders to issue guidelines on the topic of driving and the person with epilepsy (29). Recommendations from the conference included (i) a seizure-free interval of 3 months, (ii) allowances for purely nocturnal seizures, and (iii) a provision allowing driving when there is an established pattern of a prolonged and consistent aura (29).

It is challenging to determine the duration of seizure freedom that should be required to appropriately balance public safety and overly arduous restrictions on a person with epilepsy. Seizure-free intervals adopted by jurisdictions vary widely and have many unique exceptions (31). State regulatory agencies and the Epilepsy Foundation of America Web site (www.epilepsy.com) can be contacted for current laws governing driving and epilepsy, which has been recently updated (32). Though there is a range of restrictions among states, it has yet to be shown whether tighter restrictions are associated with decreased driving and accidents by persons with epilepsy.

In an editorial, Krumholz suggested that it is time to consider uniform laws governing epilepsy and driving throughout the United States (33). International rules on driving have been reviewed, and because of the high variability among individual countries, the appropriate national authority should be consulted to determine current local laws regarding driving before traveling to these nations (34).

Six states currently have laws that require health care providers to report persons with epilepsy to the appropriate state driving authorities. The rationale behind physician reporting is the concern that a person with epilepsy will not reliably self- report the presence of active or recurrent seizures to the proper authority. Laws that require a health care provider to report a person with epilepsy to authorities are criticized as impairing the physician–patient relationship and thus compromising optimal medical care. The premise is that when physicians are required to report epilepsy to driving authorities, persons with epilepsy may conceal information about their seizures to avoid being reported and potentially losing their license (27). Of persons with epilepsy who had been counseled about driving laws, only 27% reported their condition to the appropriate authorities (28). The low percentage of self-reporting may partially be attributed to lack of counseling on behalf of the health care professional. In a recent review of ER visits requiring self-reporting to the driving authorities, <10% were counseled in a major metropolitan city in the southwest (35); in another survey, only 13% of providers knew the appropriate requirements in any event (36). In California, which is the most populous state requiring physician reporting, a survey again suggested that the physician reporting requirement impaired medical care and the doctor–patient relationship (37). There are no available studies showing that physician reporting reduces seizure-related automobile crashes. In Canada, a conference of invited experts concluded that the laws requiring health care professionals to report persons with epilepsy to authorities should be abolished and suggested that driving laws be uniform across Canada (38). McLachlan et al. reported on the impact of mandatory reporting to driving authorities in one province requiring reporting compared to a province that does not. Their conclusion was that mandatory reporting of the person with epilepsy to the driving authorities by physicians did not reduce accident risk. They go on to suggest that the reporting requirements may be excessive compared to other medical conditions or nonmedical risk factors (39). In a comparison between one state with mandatory reporting and one without, there was no difference found in rate of physician counseling regarding driving, driving despite between told not to, or automobile accidents (40). An editorial by emergency department physicians suggested that mandatory reporting of seizures be abolished in the United States (41). This editorial highlighted several other medical conditions and situations that are associated with a similar or higher relative risk of a car crash compared with epilepsy, such as sleep, apnea, diabetes, dementia, and cell phone use (38).

EMPLOYMENT AND THE PERSON WITH EPILEPSY

QOL surveys have identified employment issues and concerns of persons with epilepsy as significant (1,2). The economic impact that epilepsy has on society is huge (more than $10.8 billion/year) and is largely attributable to indirect employment- related costs, which account for 85% of all epilepsy costs (42). Persons with epilepsy have a lower prevalence of employment (43). They are also reported to have lower household incomes, which are estimated to be 93% of the US median income (44), compared with the general population.

In the United States, the rate of unemployment for persons with epilepsy is reported to be between 25% and 69% (44,45). Although many factors are likely to contribute to the high rate of unemployment among persons with epilepsy, poorly controlled epilepsy is associated with a high level of unemployment (45). Age of epilepsy onset also impacts employment status, with an earlier age of onset correlating with work difficulties later in life (46). In patients with adult-onset epilepsy, initial seizure control or lack of control does affect work status. Newly diagnosed, unprovoked seizures in adults do not seem to negatively impact employment rates. The same study associated the development of refractory seizures in adults with reduced income (47).

Many persons with epilepsy have to deal with the reality of employment discrimination. A survey of young persons with epilepsy enrolled in a job training program in Ireland indicated that 50% of the participants believed they were being actively discriminated against when seeking employment (48). A similar percentage of employed persons with epilepsy in Australia felt they were discriminated against (30). Widely available public education regarding epilepsy has the potential of reducing stigma within the community and, hopefully, within workplaces (49,50).

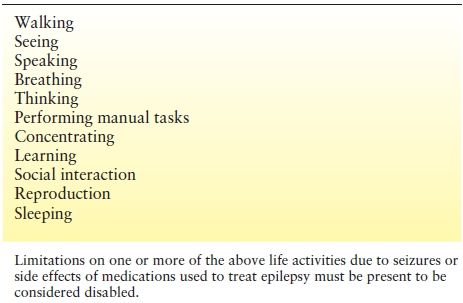

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (51) was enacted in 1990 to combat job discrimination against individuals with illnesses. The law was intended to help persons with epilepsy and persons with other disabilities obtain and retain employment. A prominent feature of the ADA is that a person with a covered malady cannot be discriminated against if “reasonable accommodations” can be made that would allow the covered individual to obtain or remain in a specific job. But the ADA exempts employers with 15 or fewer employees, thereby eliminating many small businesses. Furthermore, what constitutes a reasonable accommodation was left open to interpretation. The standard may be based on the actual cost of any modifications required that allow a person to keep a specific job. Finally, the employee must be able to perform the “essential” tasks of the job. Administrative and court rulings have made it clear that the protection sought has not been achieved (52). In a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court opinion, Justice O’Connor wrote that for an individual to be considered disabled, the person’s disability must be “permanent or long-term,” and the impairment must “prevent or severely restrict the individual from doing activities that are of central importance to most people’s daily lives” (53). The following statement summarizes the court’s opinion: “Merely having an impairment does not make one disabled for the purposes of the ADA.” This ruling and others like it have changed the thinking on what defines disability for many patients. These uncertainties and restrictive rulings by the court have prompted a reevaluation of the issue by the US Legislature, which resulted in the passage of the “ADA Restoration Act of 2008.” The law took effect on January 1, 2009. The law was passed in an effort to clarify and be more inclusive on what constitutes disability under the law. It still covers business and governmental agencies of 15 or more employees. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has reviewed and published guidelines for person with epilepsy and employers regarding employment and epilepsy issues (http://www.eeoc.gov/facts/epilepsy.html). Major life activities specifically covered in the law are highlighted in Table 94.2. The major life limitations due to epilepsy can result from seizures or the complications and side effects of medications used to treat the seizures. Specific examples of hiring practices’ do’s and don’ts for the person with epilepsy determinations about disability are fraught with complexities and should be considered on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the unique facts involved. Individual cases may require specialized legal advice. All the possible accommodations that may affect the person with epilepsy would be lengthy. A potentially helpful website, the Job accommodation network (3), with common examples of accommodation is http://www.jan.wvu.edu/media/epilepsy.html. Readily accessible social service resources can assist patients in navigating employment accommodations and disability eligibility in regard to their epilepsy (54).

Table 94.2 Life Activities that Must be Impaired to be Considered Disabled by Seizure as Defined by the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act of 2008

Certain jobs may be perfectly safe for many persons with epilepsy but other jobs may impose unacceptable risk. A person with epilepsy must carefully evaluate jobs involving dangerous machinery, or equipment heights, or situations in which there is a possibility for injury or death because of potentially dangerous conditions in the event of a seizure. Persons with epilepsy also face regulatory-imposed restrictions for some jobs. For example, a person with epilepsy’s pursuit of a commercial pilot’s license is severely limited by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (55). Similarly, a person with epilepsy wishing to obtain a commercial driver’s license (CDL) to operate a truck in interstate commerce must overcome significant hurdles imposed by the Federal Department of Transportation. The diagnosis of epilepsy and the use of AEDs generally disqualify an applicant or current driver from obtaining a CDL. A CDL is required to operate a truck with a gross weight >24,000 pounds. Although many states have mirrored the federal regulations with regard to state commercial driving laws, individual state regulations should be reviewed for accuracy. Internationally, laws vary regarding CDLs. For example, in Norway, bus and taxi drivers may not have had a seizure after age 18 (56). Tailoring the specific job to the person with epilepsy, based on the person’s unique, individual situation, should be emphasized.

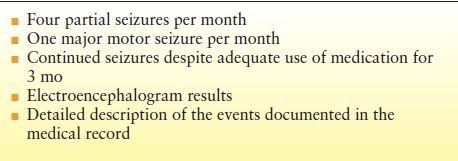

Under Social Security Administration (15) regulations, epilepsy is covered by specific listings (57). These listings, which define what constitutes a disability for the person with epilepsy, are used in determining who is eligible to receive disability payments. Persons with epilepsy are required to provide specific evidence, through medical records documenting that they “meet the listing,” as featured in Table 94.3. Other factors, such as postictal effects of seizures and side effects of prescribed medications, may be considered in determining disability, especially during a hearing or an appeals process for a denied claim. The specific listings for epilepsy are sections 11.03 and 11.02 for minor motor and major motor seizures, respectively (57). Decisions regarding SSA for epilepsy based upon the listings have been shown to be inconsistent and without evidence-based guidelines, potentially requiring further guidelines in the future (4,58).

Table 94.3 Factors Required for Consideration of Social Security Administration Disability Benefits

SPORTS AND RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES

Persons with epilepsy are often excluded or discouraged from participation in sports and recreational activities because of fear of what might occur during the activity. Since the 1960s, official recommendations regarding limitations in the participation of physical activity have been significantly liberated, and at this point, physical activity is recognized as being beneficial for persons with epilepsy. In addition, lack of leisure time and physical activity may be a detriment to persons with epilepsy. It has been shown that a low level of physical activity is a risk factor for depression in epilepsy (59) and that greater physical activity is associated with fewer days where their health limited their routine (60). However, engagement in leisure and physical activity require certain considerations.

Epilepsy and Recreational Vehicles

Motorized vehicles can potentially cause serious injury or death even in persons without epilepsy. The unpredictability of uncontrolled seizures might pose a serious threat should a seizure occur at the wrong time. Operating motorized vehicles is associated with a prolonged danger period.

A seizure that occurs while a person is piloting a private plane is likely to have disastrous consequences. Noncommercial aviation is at least partially regulated by the FAA. A third-class pilot’s license is required for all general noncommercial aviation (55). If an individual has experienced a single unprovoked seizure with no EEG abnormalities, normal brain imaging, and no additional risk factors, that person can be considered for a third-class license if he or she has not taken an AED for 4 consecutive years. The FAA uses certified examiners to assist in the decision-making process for granting licenses when there is a potential medical problem. Piloting ultralight aircraft, hang gliders, and other small aircraft may not require a license, but these are unlikely to be any safer than a private plane should a mishap occur.

Other motorized vehicles, such as motorcycles, personal watercraft, all terrain vehicle (four wheel), and boats, may pose less of a threat to a person with epilepsy than does flying. If the person with epilepsy operating the vehicle has a prolonged and consistent aura, it may allow that person the opportunity to stop and protect ones self. However, a person with epilepsy when contemplating sports activities should consider other factors. For example, drowning is a common accident among persons with epilepsy (61). The use of a personal flotation device at all times when operating or riding in any watercraft should be considered. When operating off-road vehicles, safety equipment should also be considered, especially the use of boots, shoulder pads, protective clothing, and helmets. Although a person operating such a vehicle does not require a license, specific training courses are available and are highly recommended.

In contrast, organized motor sports generally require some form of medical clearance before participation (53). The different motor sport sanctioning bodies, such as the Sports Car Club of America, the National Association of Stock Car Racers, and the Indy Car Series, all have specific requirements for a person to be allowed to drive in sanctioned events. Each series requires approval from a qualified health care professional before driving, and therefore, specific rules should be reviewed.

The Person with Epilepsy and Athletics

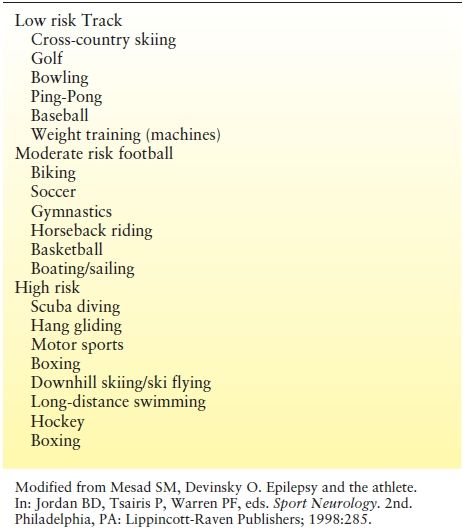

The decision to participate in individual (i.e., one-on-one) and team sports should follow those principles outlined above in order to ensure maximum benefits (and thus satisfaction) and safety. The extent to which a person with epilepsy wishes to pursue athletics is an individual decision that should be based on individual circumstances. Table 94.4 classifies risks to the person with epilepsy according to the sport.

Table 94.4 Sporting Activities Classified According to Possible Risk for the Person with Epilepsy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree