5

DYSTONIA

“Dystonia is a neurologic syndrome characterized by involuntary, sustained, patterned, and often repetitive muscle contractions of opposing muscles causing twisting movements or abnormal postures. Partly because of its rich expression and a variable course, dystonia is frequently not recognized or misdiagnosed.”1

The prevalence of generalized primary torsion dystonia in Rochester, Minnesota, was reported to be 3.4 per 100,000 population, and that of focal dystonia to be 30 per 100,000.2

PHENOMENOLOGY OF DYSTONIC MOVEMENTS

The main features of dystonia include the following:

The main features of dystonia include the following:

The movements are of relatively long duration, whereas in chorea or myoclonus, the involuntary movements are brief.

The movements are of relatively long duration, whereas in chorea or myoclonus, the involuntary movements are brief.

Both the agonist and antagonist muscles of a body part simultaneously contract to result in twisting of the affected body part.

Both the agonist and antagonist muscles of a body part simultaneously contract to result in twisting of the affected body part.

The same muscle groups are generally involved, whereas in chorea, the involuntary movements are random and involve different muscle groups.

The same muscle groups are generally involved, whereas in chorea, the involuntary movements are random and involve different muscle groups.

Other features include the following:

Other features include the following:

Primary dystonia almost always begins by affecting a single part of the body (focal dystonia) and then gradually generalizes; most often, the spread is to contiguous body parts.

Primary dystonia almost always begins by affecting a single part of the body (focal dystonia) and then gradually generalizes; most often, the spread is to contiguous body parts.

The younger the age at onset, the more likely it is for the dystonia to spread (eg, a childhood onset with leg involvement usually eventually leads to generalized dystonia, whereas an adult onset with cranial or cervical involvement usually remains focal).3,4

The younger the age at onset, the more likely it is for the dystonia to spread (eg, a childhood onset with leg involvement usually eventually leads to generalized dystonia, whereas an adult onset with cranial or cervical involvement usually remains focal).3,4

Dystonia is almost always worsened by voluntary movement. Dystonic movements may be aggravated during voluntary movement and may be termed action dystonia. Abnormal dystonic movements that appear only during certain actions are termed task-specific dystonia. An example is writer’s cramp.

Dystonia is almost always worsened by voluntary movement. Dystonic movements may be aggravated during voluntary movement and may be termed action dystonia. Abnormal dystonic movements that appear only during certain actions are termed task-specific dystonia. An example is writer’s cramp.

As the dystonia progresses, even nonspecific voluntary action can elicit dystonia; eventually, actions in other parts of the body can induce dystonic movements of the primarily affected body part, termed overflow dystonia.

As the dystonia progresses, even nonspecific voluntary action can elicit dystonia; eventually, actions in other parts of the body can induce dystonic movements of the primarily affected body part, termed overflow dystonia.

Dystonia is usually worsened by fatigue and stress and is suppressed by sleep, hypnosis, or relaxation.

Dystonia is usually worsened by fatigue and stress and is suppressed by sleep, hypnosis, or relaxation.

A unique and intriguing feature of dystonia is that the movements can be suppressed by a tactile or proprioceptive “sensory trick” (geste antagoniste); lightly touching (and sometimes simply the act of touching) the affected body part can often reduce the muscle contractions.

A unique and intriguing feature of dystonia is that the movements can be suppressed by a tactile or proprioceptive “sensory trick” (geste antagoniste); lightly touching (and sometimes simply the act of touching) the affected body part can often reduce the muscle contractions.

Surprisingly, pain is not very common in dystonia except in cervical dystonia, in which up to 75% of patients experienced pain in one study.5

Surprisingly, pain is not very common in dystonia except in cervical dystonia, in which up to 75% of patients experienced pain in one study.5

Dystonia can present with tremor (dystonic tremor) or myoclonus (dystonia–myoclonus). Dystonic tremor resulting from cervical dystonia can be distinguished from essential tremor because the dystonic tremor is usually less regular or rhythmic than essential tremor and is associated with a head tilt and chin deviation.

Dystonia can present with tremor (dystonic tremor) or myoclonus (dystonia–myoclonus). Dystonic tremor resulting from cervical dystonia can be distinguished from essential tremor because the dystonic tremor is usually less regular or rhythmic than essential tremor and is associated with a head tilt and chin deviation.

Rarely, children and adolescents with primary or secondary dystonia can develop a sudden and marked increase in the severity of dystonia, termed dystonic storm.

Rarely, children and adolescents with primary or secondary dystonia can develop a sudden and marked increase in the severity of dystonia, termed dystonic storm.

CLASSIFICATION OF DYSTONIA

By distribution

By distribution

Focal: affects a single body part (eg, torticollis, writer’s cramp, blepharospasm, foot dystonia, lingual dystonia, spasmodic dysphonia).

Focal: affects a single body part (eg, torticollis, writer’s cramp, blepharospasm, foot dystonia, lingual dystonia, spasmodic dysphonia).

Segmental: affects one or more contiguous body parts (eg, Meige syndrome).

Segmental: affects one or more contiguous body parts (eg, Meige syndrome).

Multifocal: involves two or more noncontiguous body parts.

Multifocal: involves two or more noncontiguous body parts.

Hemidystonia: involves half of the body; usually associated with a structural lesion (eg, tumor in the contralateral putamen).

Hemidystonia: involves half of the body; usually associated with a structural lesion (eg, tumor in the contralateral putamen).

Generalized: the entire body is affected.

Generalized: the entire body is affected.

By clinical features

By clinical features

Continual

Continual

Primary (or idiopathic) dystonia

Primary (or idiopathic) dystonia

– May be inherited or sporadic.

– Can have an early onset (younger than 26 years of age) or a late onset 26 years and older.

Dystonias with an early onset tend to become severe and are more likely to spread to involve multiple parts of the body.

Dystonias with an early onset tend to become severe and are more likely to spread to involve multiple parts of the body.

Dystonias with a later onset tend to remain focal.

Dystonias with a later onset tend to remain focal.

Secondary dystonia

Secondary dystonia

– Secondary dystonia may be generalized, segmental, focal or multifocal, and associated with other neurologic disorders.

– Unilateral dystonia/hemidystonia is often symptomatic and usually results from a stroke, trauma, arteriovenous malformation, or tumor.

Fluctuating

Fluctuating

Paroxysmal dyskinesias can vary from chorea-ballism to the sustained contractions of dystonia. Paroxysmal is the term most commonly used for periodic choreoathetotic and dystonic involuntary movements, while episodic is most commonly used for periodic ataxic involuntary movements. Paroxysmal dyskinesias are generally classified into four types (Table 5.1):6

Paroxysmal dyskinesias can vary from chorea-ballism to the sustained contractions of dystonia. Paroxysmal is the term most commonly used for periodic choreoathetotic and dystonic involuntary movements, while episodic is most commonly used for periodic ataxic involuntary movements. Paroxysmal dyskinesias are generally classified into four types (Table 5.1):6

– Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD)

Usually lasts for seconds to minutes; precipitated by sudden movement, startle, or hyperventilation; occurs many times a day; patients may experience a sensory “aura” prior to the attack.

Usually lasts for seconds to minutes; precipitated by sudden movement, startle, or hyperventilation; occurs many times a day; patients may experience a sensory “aura” prior to the attack.

The majority of cases are primary (familial with autosomal dominant inheritance or sporadic); causes of secondary PKD include multiple sclerosis, head injury, hypoxia, hypoparathyroidism, and basal ganglia and thalamic strokes.

The majority of cases are primary (familial with autosomal dominant inheritance or sporadic); causes of secondary PKD include multiple sclerosis, head injury, hypoxia, hypoparathyroidism, and basal ganglia and thalamic strokes.

Affecting PRRT2 (proline-rich transmembrane protein, which seems to manifest in embryonic neural tissue).

Affecting PRRT2 (proline-rich transmembrane protein, which seems to manifest in embryonic neural tissue).

PKD may respond to anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, especially when the paroxysmal attacks are brief; females may respond better than males.

PKD may respond to anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, especially when the paroxysmal attacks are brief; females may respond better than males.

– Paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia (PNKD)

Often consists of any combination of dystonic postures, chorea, athetosis, and ballism; may be unilateral or bilateral; longer duration and smaller frequency of attacks compared with PKD.

Often consists of any combination of dystonic postures, chorea, athetosis, and ballism; may be unilateral or bilateral; longer duration and smaller frequency of attacks compared with PKD.

Precipitated by alcohol, coffee, tea, stress, or fatigue.

Precipitated by alcohol, coffee, tea, stress, or fatigue.

Cases can be primary (familial with autosomal dominant inheritance or sporadic) or secondary, caused by multiple sclerosis, hypoxia, encephalitis, metabolic causes, psychogenic, and other conditions.

Cases can be primary (familial with autosomal dominant inheritance or sporadic) or secondary, caused by multiple sclerosis, hypoxia, encephalitis, metabolic causes, psychogenic, and other conditions.

Not sensitive to anticonvulsants.

Not sensitive to anticonvulsants.

– Paroxysmal exertional dyskinesia

Attacks are briefer than those in PNKD, lasting 5 to 30 minutes; precipitated by prolonged exercise.

Attacks are briefer than those in PNKD, lasting 5 to 30 minutes; precipitated by prolonged exercise.

Most familial cases exhibit autosomal dominant inheritance.

Most familial cases exhibit autosomal dominant inheritance.

May respond to anticonvulsant or antimuscarinic agents.

May respond to anticonvulsant or antimuscarinic agents.

– Paroxysmal hypnogenic dyskinesia

Attacks can be brief or prolonged.

Attacks can be brief or prolonged.

Several cases may be due to supplementary motor or frontal lobe seizures.

Several cases may be due to supplementary motor or frontal lobe seizures.

Diurnal

Diurnal

– Aromatic acid decarboxylase deficiency (usually in infancy): axial hypotonia, athetosis, ocular convergence spasm, oculogyric crises, limb rigidity.

– GTP (guanosine triphosphate) cyclohydrolase I deficiency (DYT5): first step in tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis, childhood onset, may be diurnal, improves with low-dose levodopa, abnormal phenylalanine loading test.

Other causes: side effect of levodopa therapy, acute dystonic reaction to neuroleptics, gastroesophageal reflux, oculogyric crisis (sudden, transient conjugate eye deviation).

Other causes: side effect of levodopa therapy, acute dystonic reaction to neuroleptics, gastroesophageal reflux, oculogyric crisis (sudden, transient conjugate eye deviation).

By etiology

By etiology

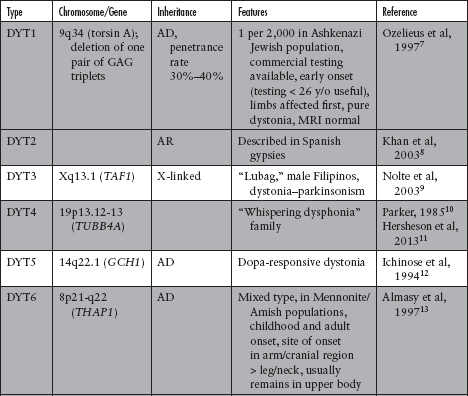

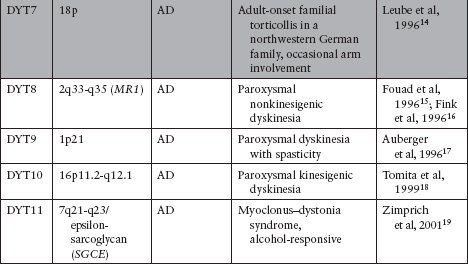

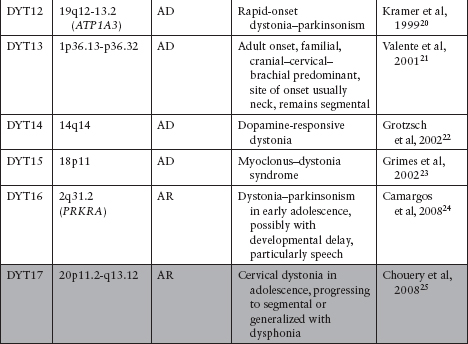

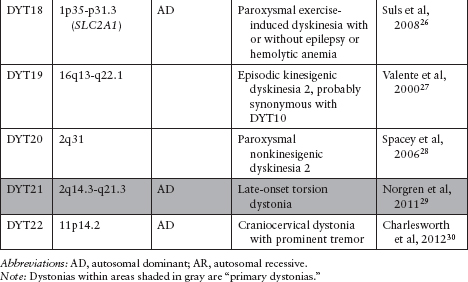

Primary (idiopathic) dystonia: may be familial (Table 5.2)7–30 or sporadic. In the pure dystonic syndromes, dystonia is the main and only clinical sign (except for dystonic tremor).

Primary (idiopathic) dystonia: may be familial (Table 5.2)7–30 or sporadic. In the pure dystonic syndromes, dystonia is the main and only clinical sign (except for dystonic tremor).

Of the DYTs, types 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 13, 17, and 21 (shaded in gray in Table 5.2) are primary dystonias.

Of the DYTs, types 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 13, 17, and 21 (shaded in gray in Table 5.2) are primary dystonias.

Dystonia-plus: “nonneurodegenerative” conditions in which signs and symptoms other than dystonia, such as parkinsonism and myoclonus, are present; these are generally not neurodegenerative disorders and are better classified as neurochemical disorders.

Dystonia-plus: “nonneurodegenerative” conditions in which signs and symptoms other than dystonia, such as parkinsonism and myoclonus, are present; these are generally not neurodegenerative disorders and are better classified as neurochemical disorders.

Among the DYTs, those with dystonia plus parkinsonism include types 3, 5, 12, and 16, and those with dystonia plus myoclonus include types 11 and 15.

Among the DYTs, those with dystonia plus parkinsonism include types 3, 5, 12, and 16, and those with dystonia plus myoclonus include types 11 and 15.

Dopa-responsive dystonia

Dopa-responsive dystonia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree