INTRODUCTION

The greying of the world and the high prevalence of mental disorders have highlighted the vulnerability of the social and health-care systems. Based on demographic forecasts, almost apocalyptic scenarios have been presented. The number of people 65 years and older will increase from about 500 million people in 2010 to about 1 billion in 2030. The diseases of the elderly and mental disorders are in general chronic, resource demanding, more or less incurable and long lasting (decades). These disorders also involve many sectors of the society; not only the health-care sector but also to a greater extent social services and informal carers, and they cause a substantial loss of well-being and life-years worldwide1. If we also add a financial crisis in the many public care systems we must consider fundamental issues such as economic burden, cost effectiveness of treatments, priority settings, equity, how to organize, finance and distribute care in any health economics analysis.

Health economics is the application of economic theory to health care2. There are, however, several methodological issues in this field, which also link to fundamental health economics questions. Some basics in health economics must also be considered. The main focus in this chapter is on dementia and similar disorders, but the principles are applicable to any mental or chronic disorder and so we have also included examples from other mental conditions.

A health economics analysis can be seen from different viewpoints such as a societal perspective or specific cost-bearers (e.g. county councils, municipalities, insurance companies)3. A societal perspective is preferable and should include all relevant costs (that is both direct costs within the health sector and indirect costs due to production losses and costs of informal care) and outcomes. Depending on the selected viewpoint, the outcome of the analysis may vary.

RESOURCE UTILIZATION AND COSTING

A key issue in all economics is the cost concept. The opportunity cost, which most economists recommend using in descriptive studies and economical evaluations, is the value of a resource in its best alternative use2. Care resources are more or less always scarce and the use of a resource in one specific way will result in some lost benefit because resources were not allocated to another option4.

Ideally, opportunity costs should be based on market prices, which in health care are not always easy to identify. For example, for an informal caregiver, who because of the care-cost demands is not working, the opportunity cost is the value of the forgone work that could have been done.

Costs can be divided into direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs and indirect costs. In a simplified approach, direct costs refer to the value of resources used and indirect costs to resources lost. Direct medical costs refer to resources used in the medical care system, such as costs of hospital care, drugs and visits to clinics. Direct nonmedical costs are those outside the medical care system, such as costs for formal community care and transports. Depending on how care is organized, costs of long-term care and home care can be regarded as a medical or non-medical direct cost.

Indirect costs are costs due to production losses (such as sick leave, early pension, impaired productivity) or mortality. Costs of informal care (see below) is a complicated issue in and are often classified as indirect costs, but this is not always obvious.

The costing process usually consists of two phases: first the use of resources is measured in terms of physical units (e.g. days in hospital, hours of home support) during a specified period of time; secondly, this resource utilization is calculated into costs. For economic studies of dementia, we have developed a process called resource utilization in dementia (RUD) (Table 17.1)11. Because the organization of dementia care varies between countries, the process must be adapted to the particular national situation. This process also includes linguistic adaption, because the meaning and the costs of care concepts (such as ‘institutional care’) may vary between countries even if the basic language is similar, e.g. if English is spoken in the UK and South Africa, it does not necessarily mean that the interpretation of care concepts is the same. In multinational trials, it is recommended that the aggregation of results from different countries is in physical units and not in costs.

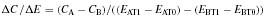

Several approaches can be used in health economics analyses (see Table 17.2)7. With the cost description (CD) approach, the costs of a single treatment are described without outcomes/effect measures and without making any comparisons with alternative treatments. In a cost analysis (CA), the costs of different treatments/therapies are compared, but there are no outcomes/effects included in the analysis. A complete health economics analysis should include both measurements of costs and outcomes and comparisons between different treatment alternatives. This is often expressed as a ratio: the the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER)

Table 17.1 Components of a resource utilization in dementia (RUD) plan38

| Patient | Caregiver |

| Accommodation/long-term care | Informal care time (for patient) |

| (Work status) | Work status |

| Respite care | (Respite care) |

| Hospital care | Hospital care |

| Outclinic visits | Outclinic visits |

| Social service | Social service |

| Home nursing care | Home nursing care |

| Day care | Day care |

| Drug use | Drug use |

Table 17.2 Different types of health economics studies

| CD | Cost description |

| CA | Cost analysis |

| CMA | Cost minimization analysis |

| CEA | Cost effectiveness analysis |

| CBA | Cost benefit analysis |

| CUA | Cost utility analysis |

| CCA | Cost consequence analysis |

| COI | Cost of illness |

where C = costs, E = outcomes/effects, A,B = treatments, Tϋ,T1 = time for assessments.

There are, however, other approaches such as net benefit analyses (net monetary benefits and net health benefits)7. Irrespective of approach, a willingness-to-pay level (for a specific outcome) is crucial.

In a cost minimization analysis (CMA) there is evidence that the effects/outcomes are similar between the treatment options and thus the analysis is focused on identifying the therapy with the lowest cost. The difference between CA and CMA is that in a CA there is no data about effects/outcomes.

In a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), the effect is expressed as a non-monetary quantified unit such as the cost per death or nursing home admission averted. Other outcomes may be functional measures such as activities in daily living (ADL) capacity, severity states of disease and cognition (e.g. scoring on different scales). In a cost benefit analysis (CBA), costs and outcomes are described in the same unit (usually monetary). Early CBA analyses had a simple human capital approach, while the modern theory of CBA is complex and includes willingness-to-pay approaches such as contingent valuation8,9. In a cost utility analysis (CUA), the effect is expressed in terms of utilities, such as quality of life. In CUA, the concept of quality adjusted life years (QALY) is frequently used (as well as other similar measures such as disability adjusted life years (DALY) and healthy years equivalents (HYE)).

In a cost consequence analysis (CCA), cost and outcomes are analysed and presented separately and there is no direct mathematical connection between these two measures.

Cost of illness (COI) studies are descriptive (such as the costs of illness of dementia in Sweden in SEK 50 billion/year). Two approaches can be used: the prevalence method and the incidence method. With the prevalence approach the costs include for all cases for a specified time period, most often one year, including those already suffering from dementia and for new cases occurring during the period in question10,11. With the incidence approach the costs for new cases during e.g. one year are estimated, here both the annual costs and future (discounted) costs are included. The choice of approach depends on the purpose of the study: if the aim is to illustrate the economic consequences of interventions, the incidence approach is preferable. If the idea is to estimate the economic burden during a defined year the prevalence approach is the best option.

Another issue in COI studies is whether to use a top-down or a bottom-up approach. In top-down analysis, the total costs for a specific resource (e.g. health-care costs) are distributed over different diseases. Such studies often rely on data from national registers or similar. The bottom-up method starts from a defined sub-population (often from a local area) with for example dementia and registers all cost of illness related to the disease, followed by an extrapolation to the total dementia population. The problem here is compensating for co-morbidity and net costs may be difficult to estimate. It is also important to specify the included cost categories (e.g. cost of informal care). COI studies can be expressed as costs per case and year or as total costs in a specific country/region. Examples of COI studies of mental disorders are seen in Table 17.3. The cost figures highlight the great variation in cost estimates and the importance of identifying the included cost categories.

Family members and friends or others close to people with mental disorders are heavily involved in their care. Their situation is of great interest from two aspects. First, mental disorders have consequences for the carers themselves. In this sense, their situation is often very stressing (it can be described in terms of burden, coping, but also in terms of morbidity and mortality).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree