Embryology of the Cranial Circulation

Key Point

Embryologic development explains the many anatomic variants of the cerebrovascular circulation.

A rudimentary description of the embryonic origins of the cranial vessels will assist in understanding the variants and anomalies that may be seen during cerebral angiography. The terminology and nomenclature of embryologic literature can be very intimidating and obscurantist to say the least; however, the major events that describe the vascular embryology of the brain are simple to understand. Moreover, such an understanding, rather than a memorization of categorically distinct variants, will allow flexibility in one’s thinking about these anomalies. Archetypal variations are easily recognized in textbooks; for the interpretation of angiograms, however, it is necessary to realize that numerous intermediate anomalous states may coexist and are rarely, if ever, exactly similar in different cases. The following synopsis of the embryology of the cranial vasculature is based largely on the classic papers by E. D. Congdon (1) and D. H. Padget (2,3,4,5,6).

Primitive Aortic Arches

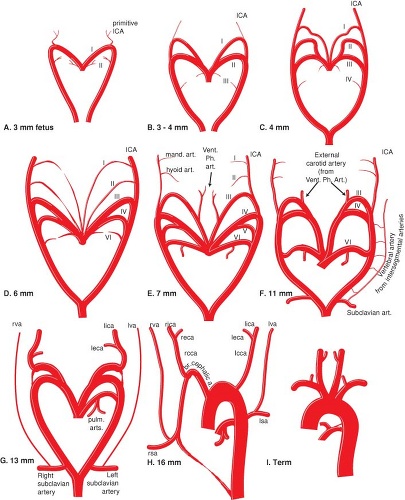

The embryologic development of the aortic arch and great vessels is described in two stages (1). A branchial stage (3- to 14-mm crown–rump length) corresponds with the arterial pattern seen in lower vertebrates, similar to that supplying the gill apparatus (branchia = gill). A postbranchial phase describes the evolution of the adult arterial pattern from the remnants of the branchial components.

The six pairs of primitive aortic arches—the existence of the fifth arches being inconstant or contentious—fill a developmental role in association with the development of the pharyngeal pouches (Fig. 7-1). This occurs by virtue of the initially cephalic location of the primitive heart and the interruption, by the pharyngeal structures, of the route between the ventral aortic sac and the dorsal paired aortae. To circumvent the pharyngeal pouches, the aortic outflow interdigitates between the pouches starting with the first set of aortic arches. As the cardiac structures migrate into the thorax, the primitive aorta is drawn caudally so that the cephalically located aortic arches, being uneconomical in disposition, regress and are replaced by other successively forming and regressing sets of arches. Not all six pairs of arches are present at a single time, as represented by synoptic diagrams.

From a point of interest in the cephalic vessels, the major events in the postbranchial phase are:

Regression of the left dorsal aorta between the third and fourth arches, such that the residuum of the left dorsal aorta becomes the source of the major carotid branches off the aortic arch (Fig. 7-1G).

Derivation of the subclavian arteries from the sixth intersegmental arteries, themselves branching from the fourth aortic arches bilaterally. The subclavian arteries assume the supply of the caudal end of the vertebral arterial network. This allows evolution of the most common adult configuration whereby the vertebral arteries, deriving from the sixth intersegmental arteries, enter the foramina transversaria of the C6 vertebral body (Fig. 7-1F).

Attenuation of the right fourth aortic arch to a caliber commensurate with a role of supplying the right subclavian artery. The right fourth dorsal aorta regresses caudad to that point, leaving the adult right subclavian artery to derive supply from the brachiocephalic artery (a remnant of the third and fourth arches), except in instances of an aberrant right subclavian artery (Fig. 7-1H).

Arterial Embryology

The cranial arterial vasculature in its adult form evolves in early fetal life through a number of simultaneous or overlapping steps. Primitive embryonic vessels without an adult derivative usually regress completely but are of interest by virtue of occasional anomalous persistence. Their closure results in hemodynamic changes that contribute in part to the genesis of other permanent vessel derivatives from the embryonic plexi. These derivatives emerge with an economic regression of the otiose remaining plexal components. Anomalies associated with early events, such as failure of regression of the primitive maxillary or hypoglossal arteries, are more rarely seen than those with later events, such as persistence of a trigeminal artery or failure of normal diminution of the territory of the anterior choroidal artery.

The 4-mm Fetal Stage

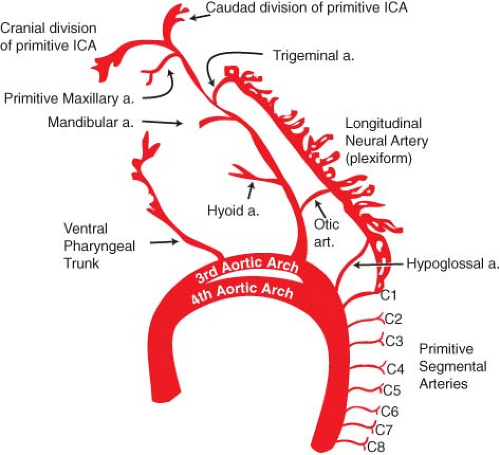

At the 4-mm fetal stage, the first and second aortic arches are involuting and their remnants, the mandibular and hyoid arteries, respectively, become incorporated as branches of the third arch (Fig. 7-2). The third arch is the precursor of the internal and common carotid artery. The hyoid artery is discussed later.

The mandibular artery has a less complicated evolution than the hyoid artery, and, in Padget’s opinion, is associated with the superficial petrosal nerve, thus represented in adult form by the artery of the Vidian canal. The mandibular artery is frequently seen in children, particularly in the setting of a hypervascular mass in the external carotid artery territory, such as a juvenile angiofibroma (7) or tonsillar hyperplasia (8).

Figure 7-2. Embryologic development of cranial arteries at the 4- to 6-mm stage. See text for discussion. Allowing for variability in timing between fetuses, parts of this diagram correlate with Figure 7-1E. |

The primitive internal carotid artery continues cephalad and gives a major anastomosis to the posterior circulation, the primitive trigeminal artery, at the level of the trigeminal ganglion. Further along its course, the primitive internal carotid artery gives a branch adjacent to the Rathké pouch, the primitive maxillary artery, which courses ventrally to the base of the optic vesicle. The primitive maxillary artery later regresses to assume a more mesial course and likely corresponds with the inferior hypophyseal artery in adults. An occasional case of an intrasellar cross-carotid anastomosis, usually in the setting of a unilateral carotid agenesis is most likely a representation of the primitive maxillary artery (9,10,11,12).

The primitive internal carotid artery forms two divisions at its most cephalad branching point:

Cranial division (the primitive anterior cerebral artery) curves around and in front of the optic vesicle to reach the olfactory area;

Caudal division (precursor of the posterior communicating artery) ends in the region of the developing mesencephalon.

Phylogenetic comparisons indicate that the cranial division of the internal carotid artery in humans is homologous with the medial olfactory artery in lower orders, such as fish and reptiles. This vessel is seen to evolve into the anterior cerebral artery as one ascends the phylogenetic hierarchy, implying that the anterior cerebral artery in humans is the direct embryonic continuation of the internal carotid artery, whereas the middle cerebral artery is a secondary branch of this vessel (12).

In the hindbrain area, the arterial vasculature consists initially of paired, separate, longitudinal neural plexi supplied cranially by the trigeminal artery and caudally by the first cervical artery. The caudal supply from the C1 segmental artery is supported by input from the otic artery at the level of the acoustic nerve and from the primitive hypoglossal artery at the level of the XII nerve. These latter two vessels are highly transient and regress early.

The 5- to 6-mm Fetal Stage

The first arch derivative, the mandibular artery, is diminishing in this stage, but the second arch derivative, the hyoid artery, continues to be robust and goes on to play an important role in the genesis of the middle meningeal artery and ophthalmic artery.

A vessel in the area ventral to the first two aortic arches, and which originates from the third arch, becomes prominent and is termed the ventral pharyngeal artery (1). This vessel is the precursor of much of the proximal external carotid artery vasculature (Fig. 7-3).

In the hindbrain, the caudal division of the internal carotid artery forms anastomoses with the cranial end of the bilateral—and as yet separate—longitudinal vascular plexi (longitudinal neural arteries). These anastomoses will form the posterior communicating artery, and as they emerge, the trigeminal arteries begin to regress. During this stage, the primitive (lateral) dorsal ophthalmic artery originating from the proximal internal carotid artery is becoming identifiable. This is one of the two embryonic sources of vascular supply to the developing eye discussed later.

The 7- to 12-mm Fetal Stage

The ventral pharyngeal system becomes more extensive; lingual and thyroidal branches are identifiable (Fig. 7-4). The ventral pharyngeal artery can be conceived of as the precursor of the lower or proximal external carotid artery. The upper portion of the external carotid artery evolves later from the hyoid artery.

In the posterior neck, longitudinal anastomoses between the cervical segmental arteries begin to fuse and form the longitudinally disposed vertebral arteries. Whereas they ultimately form a single dominant vessel, that is, the primitive vertebral artery, ipsilateral parallel longitudinal vertebral channels can persist, which explains the etiology of duplications of the vertebral arteries. More cephalad, the

longitudinal neural arteries of the hindbrain are still separate from one another for the most part but have begun to form prominent anastomoses across the midline.

longitudinal neural arteries of the hindbrain are still separate from one another for the most part but have begun to form prominent anastomoses across the midline.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree