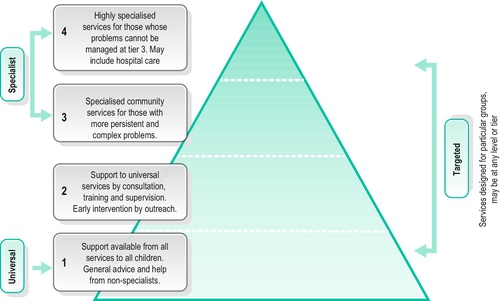

25 CHAPTER CONTENTS An Introduction to Children and Young Peoples’ Mental Health Key Drivers of Service Development in the UK Every Child Matters (ECM) (DfES 2004) Healthy Minds: Promoting Emotional Health and Wellbeing in Schools (OFSTED 2005) National CAMHS Review: Children and Young People in Mind (DH 2008a) The Children and Young Persons’ Act (2008) The Targeting Mental Health in Schools (TaMHS) Programme (DCSF 2008–2011) Healthy Lives, Brighter Futures: The Strategy for Children and Young People’s Health (DH 2009a) Think Family Toolkit (DCSF 2009a) The Evidence Base to Guide Development of Tier 4 CAMHS. K. Kurtz Report (DH 2009b) Better Outcomes, New Delivery (BOND) (DfE 2012) CHILDREN’S AND YOUNG PEOPLE’S EMOTIONAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING COMMON PRESENTATIONS OF MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN CAMHS Occupational Therapy Assessments and Outcome Measures The Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA) Short Child Occupational Profile (SCOPE) The Sensory Integration and Praxis Test (SIPT) Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) The Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile The Assessment of Communication and Interaction Skills (ACIS) The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) The complexity of the contextual factors influencing children’s and adolescent’s emotional health and wellbeing presents occupational therapists working in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) with opportunities and challenges. As well as focusing on the child’s mental health needs, occupational therapists’ professional reasoning must also accommodate an appreciation of the child’s natural developmental changes, the need for parental roles to develop alongside these, and the various social systems in which the child is living (including the culture and ethnicity of the family, their school, their friendship circle and the wider community). Practitioners must also understand the different services and agencies that may be involved from public, private and third sectors, as well as government policy and other drivers. Additionally, they must be familiar with the law influencing how services are delivered. The different services and agencies that may be involved from public, private and third sectors, government policy and other drivers; and the law influencing how services are delivered. With these contextual factors paramount in CAMHS’ work, this chapter adopts a UK orientation in its discussion of occupational therapists’ work. CAMHS comprises a range of agencies, services and individuals dedicated to the mental healthcare of children and young people aged between 0 and 18 years, and their families. It is usual for a child to be defined as a person under the age of 12 years and an adolescent as aged between 12 and 18 years. Adolescents are sometimes referred to as young people or abbreviated to YPs. As with other fields of mental health practice, practitioners are striving to reduce stigma and promote positive mental health and timely access to services. Often the term ‘mental health’ has negative connotations. In their Scottish study, Secker et al. (1999) found that some young people found it difficult to consider the term ‘mentally healthy’ in a positive light at all, and focused instead on particular associations that the words ‘mentally’ and ‘healthy’ had for them. ‘Healthy’ was linked with physical health and ‘mentally’ was associated with mental ill-health. The stigma of mental illness remains a challenge when helping children, young people and their families to access support and engage with appropriate services. With this in mind, there has been a move towards calling such services ‘Emotional Health and Wellbeing Services’, as opposed to ‘Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services’. However, since this is relatively new thinking, this chapter continues to use the term CAMHS in order to reflect the contextual literature and practice guidance that continues to shape practice in this field in the UK. Integral to tackling stigma is the idea of positive mental health. This is true across mental health practice in general but it is, arguably, a particularly important feature of work with children and young people. Rethink (2012) highlighted that everyone has ‘mental health’ and urged mental health service providers to consider the phenomenon of mental health in ordinary terms, such as: the way we feel about ourselves and the people around us; our ability to make and keep friends and relationships; our ability to learn from others; our capacity to develop psychologically and emotionally; our strength to overcome difficulties and challenges; our confidence and self-esteem; our ability to make decisions and having belief in ourselves. Occupational therapists endeavour to support these traits when considering children’s and young peoples’ needs. It is an approach which echoes the World Health Organization’s (WHO 2010) perspective of mental health, which it defines as a state of wellbeing, in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community. (See Ch. 2 for further discussion of wellbeing.) Since the late 1990s, CAMHS have undergone major organizational changes in the UK. These have re-shaped services and re-emphasized the need for all professions to demonstrate their responsiveness to individuals’ needs. Aiming to reduce stigma and develop interventions which promote positive emotional health and wellbeing for all, the changes have re-affirmed a focus on the following practice issues: ■ The importance of involving parents ■ Inter-agency working ■ Easily accessible services and early intervention ■ Reducing the stigma associated with mental health difficulties ■ Responding to what service users want ■ The prevention of ill-health ■ Rigorous quality assurance and measurement of outcomes ■ Delivering services that are personal, equitable, accountable and culturally sensitive ■ Extra support for families from disadvantaged backgrounds ■ Healthy environments in the public sector which promote physical activity ■ Schools-based interventions ■ Transitional support from adolescent to adult services ■ Developing intensive community teams to prevent or shorten hospital admissions ■ Greater recognition of the link between mental and physical health – including strengthening the provision of mental healthcare to people with physical illness and the quality of physical healthcare provided to people with mental health problems in general hospitals and primary care. What follows is an overview of some of the main legislative and policy drivers in the UK that have brought about the organizational changes described above. This UK government initiative for England and Wales was based on the Every Child Matters (ECM) Greenpaper from 2003. It was produced partly in response to the death of Victoria Climbié, who was abused, tortured and murdered by her great aunt and partner in 2000, in the UK. ECM (DfES 2004) influenced school inspection criteria and built on existing plans to strengthen preventative services by focusing on four key themes: 1. Increasing focus on supporting families and carers 2. Early intervention 3. Integrated services, with clear lines of accountability 4. Ensuring people working with children are valued, rewarded and trained. ECM (DfES 2004) promoted five outcomes most important to all children and young people (CYP), not just those using CAMHS: being healthy, staying safe, enjoying and achieving, making a positive contribution to the local community and wider society, in which they are living, and achieving economic wellbeing. This latter outcome relates to progression to further education, employment or training on leaving school, living in decent homes and sustainable communities, having access to transport and material goods, and living in households free from low income. This report by the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills emphasized the importance of mental health as part of education curricula. It called for mental health awareness training for education staff and advocated a whole-school approach to emotional health organized through the National Healthy School Standard (NHSS) programme, the Personal Social and Health Education (PSHE) curriculum, and the Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) curriculum resource. Schools were seen as less stigmatizing locations for CAMHS provision and clearer procedures for CAMHS referral were put in place. Voluntary organizations – such as youth offending schemes and counselling services (see Useful resources) – were also used as venues where appropriate. The 2007 document (updated in 2011) set out principles to help commissioners and service providers to improve the suitability of a wide range of NHS and non-NHS health services for young people. The quality criteria covered 10 topic areas: accessibility, publicity, confidentiality, consent, environment, staff training, skills, attitudes, values and joined-up working across agencies. It also established young people’s involvement in the monitoring and evaluation of their ‘patient experience’. This independent review of CAMHS post-2004, focused on developing effective, integrated child- and family-centred services to improve mental health and psychological wellbeing. To do this, it promoted universal services (focusing on promotion, prevention and early intervention) and specialist services offering accessible and timely and evidenced-based support. Universal, targeted and specialist services are described in more depth later in the chapter. It required all CAMHS staff to have a clear understanding of their roles and appropriate skills and competencies. This provided for the wellbeing of children and young people and private fostering, with a particular focus on older young people in care and those making the transition from care. It is closely linked to other legislation such as the Protection of Children Act (1999), the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act (2006), and the Childcare Act (2006). This formed part of the UK government’s wider programme of work to improve the psychological wellbeing and mental health of children, young people and their families. TaMHS aimed to help schools deliver timely interventions and approaches to help those with mental health problems and those at increased risk of developing them. This guidance strategy built on the National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services (DH 2004), Every Child Matters (DfES 2004), and the National Health Service Next Stage Review Government paper (DH 2008b) by promoting high-quality services and minimizing health inequalities. This guidance reformed services for vulnerable children, young people and adults to enable early identification of families at risk of poor outcomes, and to strengthen families’ self-help skills. This report heralded a move away from an over-exclusive focus on inpatient care to ‘wrap-around’ provision across multiagency services including in-reach, out-reach, intensive and crisis community services, day provision, therapeutic fostering and other services. It identified certain groups at a high risk of developing mental health problems such as young offenders from criminal backgrounds, looked after children, children with learning and/or emotional and/or behavioural difficulties, children with a chronic physical illness and/or physical disability and/or sensory impairments, children who have been sexually, physically or emotionally abused, children whose parents have a mental health problem and/or a substance misuse problem, children who have experienced or witnessed sudden or extreme trauma, and children who are refugees. The report highlighted that good-quality services should be equitable, accessible, acceptable, appropriate, effective, ethical, and efficient. As healthcare practices have developed, the focus has been on the need for credible evidence of its effectiveness through the use of outcome measures. The UK government’s mental health strategy (DH 2011a) stressed the importance of early intervention in emerging emotional and mental health problems for children and young people. As part of this strategy, the Department of Education funded a 2-year sector-led BOND programme aimed at building on the capacity of voluntary and community sector organizations to develop the standard and range of early interventions. They would also have a role in the purchasing and commissioning of services. The Children, Young People and Families Specialist Section of The College of Occupational Therapy (COT: www.cot.co.uk) and its regional forums also influence service delivery in the UK by developing knowledge and skills, supporting continuing professional development and practitioner networking, and promoting research and evidence-based practice. Arising from the UK government strategy document ‘Together We Stand’ (Social Services Inspectorate (SSI) 1995), a four-tiered framework was used to conceptualize CAMHS as a multi-levelled set of inter-related services. Each level aimed to address the different needs of children and young people. These needs ranged from stresses and worries, to more severe mental health problems such as eating disorders and psychosis. Since then, the CAMHS Review (DH 2008a) raised the need for greater integration with other services and this has led to the universal, targeted and specialist services referred to earlier. Although interpretation can vary locally, this classification aims to show which services are available to everyone and which are available only to some. work with all children and young people. They promote and support mental health and psychological wellbeing through the environment they create and the relationships they have with children and young people. They include early years providers and settings such as childminders and nurseries, schools, colleges, youth services and primary healthcare services such as GPs, midwives and health visitors. Universal services equate to Tier 1 Service provision. are engaged to work with children and young people who have specific needs; for example, learning disabilities, school attendance problems, family difficulties, physical illness or behaviour difficulties and those in care. work with children and young people with complex, severe and/or persistent needs. This includes CAMHS at Tiers 3 and 4 of the conceptual framework (though there is overlap here, as some Tier 3 services could also be included in the ‘targeted’ category). It also includes services across education, social care and youth offending that work with children and young people with the highest levels of need; for example, in pupil referral units (PRUs), special schools, children’s homes, intensive foster care and other residential or secure settings. The CAMHS Review (DH 2008a) defined the tiers (illustrated in Fig. 25-1) as follows: FIGURE 25-1 CAMHS tiers and services. Adapted from Nixon B 2006 Reflecting on the competencies/capabilities needed by the workforce in order to work effectively with children and young people around issues of mental health. A discussion document: CSIP, National CAMHS Workforce Programme, with permission from the author and Public Health England. These services are provided by practitioners working in universal services (such as GPs, health visitors, teachers and youth workers), who are not necessarily mental health specialists. They offer general advice and treatment for less severe problems, promote mental health, aid early identification of difficulties and refer to more specialist services. These services are provided by specialists working in community and primary care settings in a unidisciplinary way (such as primary mental health workers, psychologists and paediatric clinics). They offer consultation to families and other practitioners, outreach to identify severe/complex needs, and assessments and training to practitioners at Tier 1 to support service delivery. These services are provided by a multidisciplinary team or service working in a community mental health clinic, child psychiatry outpatient service or community settings. They offer a specialized service for those with more severe, complex and persistent mental health problems. These services are for children and young people with the most serious problems. They include day units and highly specialized outpatient teams and inpatient units, which usually serve more than one area. Occupational therapists work across all tiers (as illustrated in the case studies later in the chapter) but are usually employed within specialist tiers 3 and 4. In this section, we will consider the concepts of risk and resilience and how they contribute to mental wellbeing. Risk factors can be cultural, economic or related to medical conditions, which impact on opportunities and resources available to a child. These risk factors may affect the child’s ability to become a meaningful member of the home, school or community. Risk factors can be internal (or intrapersonal) or external (involving family, school and community members). Resilience is the presence of protective factors, which can be seen as those qualities or situations that help minimize or modify potential negative outcomes (see also Ch. 2 for further discussion of resilience). Occupational therapy assessments should always highlight the strengths and needs of service users. Awareness of risk and resilience factors for mental health difficulties in children (see Table 25-1) will also guide therapists’ interventions and develop a ‘wellness’ approach by focusing on the development of ‘life tools’ such as friendship, assertiveness or problem-solving skills, or the ability to access physical activities to promote resilience. TABLE 25-1 Risk and Resilience Factors Adapted from National CAMHS Review (DH 2008a).

Emotional Health and Wellbeing of Children and Young People

INTRODUCTION

An Introduction to Children and Young Peoples’ Mental Health

Key Drivers of Service Development in the UK

Every Child Matters (ECM) (DfES 2004)

Healthy Minds: Promoting Emotional Health and Wellbeing in Schools (OFSTED 2005)

You’re Welcome Quality Criteria (DH 2007) and You’re Welcome: Quality Criteria for Young People Friendly Health Services (DH 2011b)

National CAMHS Review: Children and Young People in Mind (DH 2008a)

The Children and Young Persons’ Act (2008)

The Targeting Mental Health in Schools (TaMHS) Programme (DCSF 2008–2011)

Healthy Lives, Brighter Futures: The Strategy for Children and Young People’s Health (DH 2009a)

Think Family Toolkit (DCSF 2009a)

The Evidence Base to Guide Development of Tier 4 CAMHS. K. Kurtz Report (DH 2009b)

Better Outcomes, New Delivery (BOND) (DfE 2012)

MODELS OF SERVICE DELIVERY

Universal Services

Targeted Services

Specialist Services

Tiered and Targeted Services

Tier 1

Tier 2

Tier 3

Tier 4

CHILDREN’S AND YOUNG PEOPLE’S EMOTIONAL HEALTH AND WELLBEING

Risk and Resilience

Risk Factors

Resilience Factors

Child

Genetic influences

Low IQ and learning difficulties

Specific developmental delay

Communication difficulties

Difficult mental and emotional traits

Physical illness, especially if chronic and/or neurological

Poor academic performance

Low self-esteem

Secure early relationships

Being female

Higher intelligence

Mentally, physically and emotionally contented as an infant

Positive attitude, problem-solving approach

Good communication skills

Planning skills, belief in control

Humour

Religious faith

Capacity to reflect

Family

Overt parental conflict

Family breakdown

Inconsistent or unclear discipline

Hostile and rejecting relationships

Failure to adapt to child’s changing developmental needs

Abuse – physical, sexual and/or emotional

Parental psychiatric illness

Parental criminality, alcoholism and personality disorders

Death and loss – including loss of friendships

At least one good parent–child relationship

Affection

Clear, firm and consistent discipline

Support for education

Supportive long-term relationship/absence of severe discord

Environment/Community

Socioeconomic disadvantage

Homelessness

Disaster

Discrimination

Other significant life events

Wider supportive network

Good housing

High standard of living

A high-morale school with positive policies for behaviour, attitude and anti-bullying

A school with strong academic and non-academic opportunities

Range of sport/leisure opportunities

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree