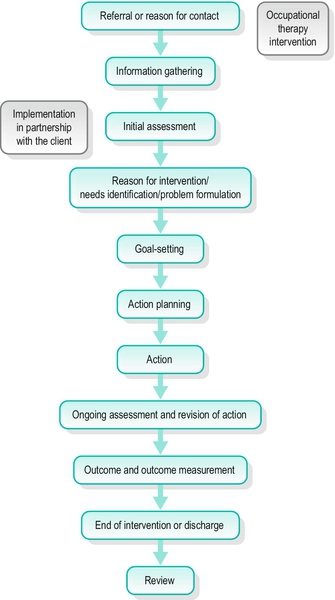

4 CHAPTER CONTENTS THE OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY PROCESS On-Going Assessment and Revision of Action Psychodynamic Frame of Reference Basic Assumptions About People Human Developmental Frame of Reference Basic Assumptions About People Occupational Performance Frame of Reference Basic Assumptions About People Chapter 3 delineated the knowledge base of occupational therapy, including philosophical beliefs and theories, and introduced the structures that are used to organize that knowledge for practical application: frames of reference, approaches and models for practice. This chapter looks in more detail at how the occupational therapy knowledge base informs and supports practice. The chapter is in three parts. The first part outlines the content of occupational therapy practice, including the goals of intervention, people who might benefit from occupational therapy, legitimate tools for practice, the skills of the occupational therapist and the art of occupational therapy. The second part describes the process by which occupational therapy is delivered. There are a number of stages in this process but it should not be seen as finite or linear: occupational therapy is individualized, iterative and complex. The third part gives examples of occupational therapy frames of reference used in the field of mental health: the psychodynamic, human developmental and occupational performance frames of reference. Practice can be described as the actions taken by the therapist to serve the needs of the people they work with (Agyris and Schon 1974). A definition of the structure and scope of occupational therapy practice should derive from the philosophical and theoretical base of the profession, not from the constraints and demands of the service setting, although the way an intervention is carried out will be influenced by such external factors. Only if practice is based on a coherent philosophical and theoretical framework can the therapist make skilled predictions about the outcomes of intervention. We will look at the content of practice under five headings: ■ Populations served ■ Legitimate tools ■ Core skills ■ Professional artistry. The word outcome refers to two different things: the changes that are expected to occur as a result of intervention, the intended outcomes, and the results of intervention, the actual outcomes. Goals are specific and positive results to be attained by an individual from planned therapeutic interventions. Process goals are the conditions to be achieved during an intervention, such as an individual arriving on time for their sessions. Outcome goals are statements of measurable changes that the intervention is designed to bring about. Desired outcomes are discussed with those involved before beginning the intervention, often following a baseline assessment to determine the current level of performance and set goals. After an agreed period of intervention, the assessment is repeated. By comparing the assessment results before and after intervention it is possible to see what changes have taken place, that is, to measure the outcomes of intervention. (See Ch. 5 for a detailed discussion of assessment and outcome measurement.) The focus of the intervention is usually agreed jointly, to produce a set of individualized outcome goals. If the overall goal of intervention is likely to take some time to achieve, it can be broken down into a sequence of short-term goals that represent steps to be taken towards reaching the long-term goal. For example, an individual’s long-term goal may be to find full-time, paid employment. If the person has not worked for a long time, a short-term goal on the way to achieving this might be to establish a regular pattern of sleeping at night and waking at the same time every morning. The occupational therapy premise, that people influence their health by what they do, can be applied to a wide range of problems once the appropriate specialist knowledge and skills to support it have been acquired. Anyone who has problems of doing, whatever the person’s age, gender or diagnosis, could potentially work with an occupational therapist. In practice, occupational therapists work in two main settings: statutory services and the social field. The occupational therapist traditionally worked with people in a medical setting, which predetermined, to some extent, the range of problems seen, the degree of dysfunction people were experiencing and the amount of time the therapist could spend on intervention. As the profession continued to expand into new areas, people have also been encountered in other settings, such as social services departments, educational settings, health centres, community centres, day hospitals, day centres, prisons, the workplace and people’s own homes. Occupational therapists increasingly work across service boundaries, in partnership with other agencies and other professionals, to provide integrated services (College of Occupational Therapists 2006). Referrals often come from a doctor or other professional who makes the initial decision about who would benefit from occupational therapy. The occupational therapist accepts referrals on the basis of information gained from the referral and an initial assessment with the person referred. In some settings, such as continuing care units, occupational therapists select people to work with from the unit’s population. In the multidisciplinary team, the decision about which professional should work with a particular individual is usually made by all the team members. An increasing number of people are referring themselves for occupational therapy, in part due to an increase in private practice. In recent years, occupational therapists have extended their practice into a range of new areas outside mainstream health and social services. A Brazilian occupational therapist, Sandra Galheigo (2005, p. 87), called this ‘the social field’ because occupational therapy, with its humanistic principles and practices, has a significant contribution to make to social affairs. The movement towards a more socially embedded way of working has been supported by two parallel developments: increased awareness of the contribution that occupational therapy can make to addressing occupational needs not met by hospital-based models of healthcare, and theoretical developments within the profession (Lorenzo 2004; Watson 2004; Galheigo 2005; Wilcock 2006; Crouch 2010; see also Chs 12, 13 and 29). Galheigo (2005) highlighted the need for an occupational therapy vocabulary ‘to refer to those in need … excluded, marginalized, vulnerable survivors, deviant, under apartheid, disadvantaged, disaffiliated’ (p. 87) that would leave no room for misinterpretations of ‘the phenomenon of inequality’ (p. 88). As described in the last chapter, occupational therapists are developing a new vocabulary, using such terms as occupational imbalance, occupational deprivation (Wilcock 2006) and occupational injustice (Townsend and Wilcock 2004), to describe their professional purpose and goals in terms of occupational needs. This enables them to identify the occupational needs of people who do not necessarily have a medical diagnosis, including those living in chronic poverty, refugees, homeless people or those displaced by natural disasters. Occupational therapists working in these areas take a public health, health promotion and/or community development role, focusing on communities and populations rather than individuals or small groups. The social field of occupational therapy is discussed further in Ch. 29. The occupational therapist may use a variety of techniques and media during an intervention. Mosey (1986) described the permissible means of carrying out occupational therapy as the profession’s legitimate tools. These tools are: the self, activities and the environment. The relationship between the therapist and the client is an important part of the therapeutic process, from first meeting a person who has been newly referred, through coping together with the successes and setbacks of the intervention process, to ending the relationship on a positive note. Ideally, the therapeutic relationship is a partnership or collaboration between therapist and the client, in which the goals and methods of intervention are negotiated throughout the process. If an individual is unable to take a full part in negotiating the process, because of illness or disability, the therapist has a responsibility to facilitate their involvement as far as possible and to protect their interests to the best of the occupational therapist’s ability (see also Ch. 22). Mosey (1986) identified 11 elements that contribute to the therapist’s ability to relate effectively to the people they work with: ■ a perception of individuality – recognition of each person as a unique whole ■ respect for the dignity and rights of each individual ■ empathy – ability to enter into the experience of another person without losing objectivity ■ compassion or sympathy – willingness to engage with another person’s suffering ■ humility – recognition of the limits of one’s own knowledge and skill ■ unconditional positive regard – concern for the individual without moral judgements on their thoughts and actions ■ honesty – telling the truth to the people they work with; this is an aspect of being respectful ■ a relaxed manner ■ flexibility – ability to modify own actions to meet the demands of a situation ■ self-awareness – ability to reflect on one’s own reactions to the world and on the effect one is having on the world in any given situation ■ humour – a lightness of approach which, used appropriately, can facilitate the therapeutic process. Peloquin (1998) described the occupational therapist being with an individual by doing with them, and identified empathy as the most important element of the therapeutic relationship. Empathy involves the therapist turning to an individual in a genuine attempt to make a positive relationship, recognizing both what they have in common and what is unique about the person, entering into their experience, connecting with their feelings and being able to recover from that connection so that the therapist is not damaged by the therapeutic encounter. The therapist uses interpersonal skills to deal with a whole range of needs, such as engaging the initial interest of someone with a volitional disorder, supporting a bereaved person through the grieving process, helping someone to express difficult feelings appropriately, valuing a person with chronic low self-esteem and helping carers to work out how best to balance their own needs with their caring role. These interpersonal skills can be the most valuable resource in an intervention. Activities are the means by which each person interacts with the world and the main therapeutic tools used by occupational therapists to bring about changes in an individual’s function and performance. Activity is a flexible and adaptable intervention that can be used with all people in many different contexts to achieve diverse outcomes. The use of activity as a therapeutic tool requires that the therapist has a range of skills for manipulating activity, including analysis, synthesis, adaptation, grading and sequencing. Activity analysis is the process of ‘breaking up an activity into the components that influence how it is chosen, organized and carried out in interaction with the environment’ (ENOTHE 2006). Activity analysis enables the therapist to evaluate the therapeutic potential of activities and select or design the most appropriate ones for each situation. For example, activity analysis of football reveals that it is socially valued by many young people, so that they are keen to play, and that it makes variable physical and social demands on the players, depending on the position they play. Analysis also shows that five-a-side football uses a smaller pitch and makes less physical demands on the players, making it a more suitable activity for people who are not fully fit. The therapist selects activities that have the greatest potential to meet the person’s needs, develop their skills and engage their interest. Alternatively, activity components may be combined into new activities (activity synthesis) that will better achieve these goals. For example, a craft activity could be done in a group so that interpersonal demands are added to the other skills required for the performance of the activity. Activity adaptation means adjusting or modifying the activity to suit the individual’s needs, skills, values and interests. For example, a traditional craft such as macramé could be done with modern materials to produce a modern piece of jewellery that an individual finds attractive. Activity grading means adapting an activity so that it becomes progressively more demanding as a person’s skills improve, or less demanding if their function deteriorates. For example, walking can be done for longer or over more difficult terrain to increase stamina. Activity sequencing means ‘finding or designing a sequence of different but related activities that will incrementally increase the demands made on the individual as her/his performance improves or decrease them as her/his performance deteriorates. It is used as an adjunct or alternative to activity grading’ (Creek 2003, p. 38). These techniques are described more fully in Ch. 6. People function within human and non-human environments that influence both what they do and how they do it, by providing supports and barriers to occupational performance. For example, living in a town centre provides easy access to shops and other community facilities (support) but means that a person has to travel a long way to their allotment, located on the edge of town (barrier). A person’s activities are shaped by environmental factors and those activities also change the environment. For example, washing the floor changes the physical environment and visiting a friend changes the human environment. A third aspect that may be changed by activity is the person performing it, who develops skills and abilities as they adapt their performance to suit the environment. A person’s environment consists of two main elements (Hagedorn 1995): ■ Content – the physical and human elements in the environment ■ Demands – the effect the environment has on behaviour. For the occupational therapist, a third element is the potential for adaptation of the content and demands of the environment. The goal of intervention may be to enable adaptation to the environment, to adapt the environment to suit the person’s needs and abilities, or to organize a move to a different environment. When planning and implementing an intervention with an individual, the therapist considers many aspects of the environment: home; working environment; local area and resources; wider living environment, such as the town or geographical location; transport infrastructure; and potential new environments, such as a care home. The therapeutic encounter always takes place within an environment that can be adapted or manipulated to change its demands and achieve the desired outcomes, whether it is a specialized intervention setting or the home or workplace. Occupational therapists are characteristically flexible, innovative and responsive to the people with whom they are working and the context within which intervention is taking place. In order to achieve this flexibility, the occupational therapist requires a wide range of skills. Some skills are common to all therapists, whatever field they are working in, for example analysing and adapting activities. Other skills are developed for a specific field of practice. An example of a specific skill is integrated memory training, which is not requisite for every area of mental health practice (see Ch. 19 which is about older people and refers to memory clinics). Skills that are required by all occupational therapists are called core skills. The College of Occupational Therapists in the UK defined core skills as ‘the expert knowledge and abilities that are shared by all occupational therapists, irrespective of their field or level of practice’ (College of Occupational Therapists 2009, p. 4). These core skills were identified as: ■ Assessment is a collaborative process through which the therapist and the client are able to identify and explore functional potential, limitations, needs and environmental conditions. ■ Enablement is the process of helping clients to take more control of their lives, by identifying what is important, setting goals and working towards them. ■ Problem-solving is a process involving a set of cognitive strategies that are used to identify occupational performance problems, resolve difficulties and decide on an appropriate course of action. ■ Using activity as a therapeutic tool involves using activity analysis, synthesis, adaptation, grading and sequencing to transform everyday activities into interventions. ■ Group work involves planning, organizing, leading and evaluating activity groups. ■ Environmental adaptation involves assessing, analysing and modifying physical and social environments to increase function and social participation. The occupational therapist’s skills are made up of three elements (Creek 2007): 2. Knowledge and understanding: including concepts, theories, frames of reference, approaches and models (see Ch. 3). 3. Thinking: including clinical reasoning, decision-making, reflection, analysis and ethical reasoning. These skills are discussed in the next section. Thinking means using the mind and includes such mental actions as applying rules, choosing, conceptualizing, evaluating, judging, justifying, knowing, perceiving and understanding (Creek 2007). Client-centred practice requires that the occupational therapist is able to process large amounts of information in order to select the most appropriate course of action with an individual, within a specific intervention context, to achieve the best possible outcome. Collecting information and incorporating it into the decision-making process demands a range of thinking styles that the therapist can employ for thinking about different aspects of the intervention. Sinclair (2007) identified five distinct types of reasoning used by occupational therapists: ■ Theory application means using both formal theory and personal theory. Task analysis and activity analysis are core skills of theory application, and are described in Ch. 6. ■ Decision-making involves using clinical reasoning (Mattingly and Fleming 1994) to assess, plan, set priorities, predict, evaluate and determine the best approach to use in a particular context. ■ Judgement is reflection by therapists on their practice, leading to recognition of strengths, weaknesses and biases, and of how the views of others might differ from their own. Reflection takes place both during an intervention and afterwards. ■ Ethical reasoning is the process of thinking through ethical issues. It includes recognizing the ethical dimension of intervention, being sensitive to the differing views of others and maintaining personal integrity. Occupational therapy has been defined as ‘the art and science of directing man’s participation in selected tasks to restore, reinforce and enhance performance’ (AOTA 1972, p. 204). Art is ‘skill as the result of knowledge and practice’ or ‘the application of skill according to aesthetic principles’ and science is ‘a particular branch of knowledge or study’ (Shorter Oxford English Dictionary 2002). This definition identifies occupational therapy as the skilled application (art) of a particular branch of knowledge (science); therefore it is both an art and a science. The skilled application of knowledge to practice requires the occupational therapist to think about what is being done, not just follow rules, guidelines or protocols. The science of occupational therapy includes theoretical knowledge, research evidence, proven techniques and procedures. Universal theories identify the ‘general systems in which people act, general structures common to all people, and general internal systems of all people’ (Hooper and Wood 2002, p. 43). They can be learned from textbooks and lectures and serve several important functions for the occupational therapist: ■ They explain how a health condition can affect an individual’s function and impair their ability to engage in activities and occupations ■ They offer ways of understanding of how an imbalance of occupations can adversely affect the health of individuals and communities. The art of occupational therapy consists of principles, values, contextual knowledge, thinking skills, interpersonal skills and practical skills. Contextual knowledge is not universal but is specific to particular people, at particular times, in particular settings. It includes the individual’s social circumstances, educational experiences, employment, cultural background, personal beliefs and values, relationships, skills, abilities, habits, interests, needs, aspirations and social roles, and how all of these influence their occupations and activities. Contextual knowledge also includes the living environment, family, neighbourhood, workplace, financial situation, social networks and support systems, and how these support or inhibit occupations and activities. Contextual knowledge cannot be found in books but is gained through working with people in their own life world contexts. The occupational therapist applies formal theories, research evidence, techniques, skills and contextual knowledge when working out the best way forward for an individual at a particular time and place. The science of occupational therapy enables an occupational therapist to think about the implications of the individual’s health condition, the extent to which their occupational performance meets their own and society’s standards, what frame of reference or approach might be most helpful and what actions the occupational therapist could take to bring about positive change. The art of occupational therapy lies in how this understanding is translated into action. Through experience, the therapist gains both contextual knowledge about the worlds of the people they work with and practical knowledge of how occupational therapy works. Theoretical and contextual knowledge involve knowing that something is so; practical knowledge means knowing how to do something (Dreyfus and Dreyfus 1986). Knowing how is part of the art of occupational therapy. Artful practitioners know how to: ■ engage people in activities that will help them to develop skills to support their occupational performance ■ provide aids or other forms of support and adapt environments to enable occupation ■ manage their time and avoid unhealthy levels of stress. Occupational therapy is a process in the sense that change takes place over time. Life itself is more usually experienced as a process rather than as a series of steps or goals to be achieved. In many cases, going through the therapeutic process can be more important than reaching the original goal of an intervention. Occupational therapy is also a process in that the therapist’s actions follow a recognisable sequence. Mosey (1986, p. 9) said that ‘Principles for sequencing various aspects of practice refer to the way in which a profession goes about the process of problem identification and proceeds through to problem solution relative to assisting the client’. There is an accepted first step to occupational therapy intervention, followed by a logical second step, and so on. There is general agreement on the steps that make up the occupational therapy process, although not all the steps are carried out in every case. For example, in some settings the occupational therapist does not go through the whole process but merely assesses an individual and passes the results to others to carry out the rest of the intervention. For the novice therapist, the occupational therapy process may appear to be linear but the experienced practitioner uses it in a flexible and iterative way to suit the individual and the context of the intervention. The 11 steps of the occupational therapy process are shown in Figure 4-1. Two of these steps may be carried out by the therapist alone, often before meeting the person they are working with, and nine of them take place in collaboration with the individual. The occupational therapy process is outlined here but more details can be found in Chs. 5 and 6. FIGURE 4-1 The occupational therapy process. Occupational therapists come into contact with the people they work with through various routes. In some settings, the therapist sees only those people who are referred to the service or identifies potential people to work with during team meetings. Many therapists usually see everyone who is admitted to the service and make their own decisions about whom to work with. Some therapists work in drop-in centres or other settings where there is no formal system of referral. Depending on the setting, the therapist may or may not receive useful information about an individual before meeting them. Whether or not there is a formal referral, the therapist will want to know certain things about an individual before making a decision about whether or not to intervene. Certain information is necessary for the therapist to determine whether the referral is appropriate or if someone will benefit from occupational therapy intervention. If it is decided that the referral is not appropriate, the referring agent is informed of the decision and the reasons for it. The type of information sought includes the person’s medical history and presenting problem, social history and present social situation, educational and work history, current work status, reason for referral to occupational therapy, other services involved and any risk factors. This information may be gleaned from case notes, other staff, the referring agent, family, carers and the person concerned. If the referral seems appropriate and the therapist judges that the person or people might benefit from occupational therapy intervention, an initial assessment is carried out. Assessment is the basis for all intervention and must be both thorough and valid in order to ensure that intervention is appropriate. Assessment is in two stages, the initial screening assessment and more focused assessment. Assessment begins from the moment a referral is received or the therapist starts to identify those people who could benefit from occupational therapy. The initial assessment is a screening process to determine the main areas of needs of the individual and whether or not occupational therapy can be of any value at this time. Factors influencing whether or not a referral is accepted include: ■ the individual’s goals, expectations and views about occupational therapy ■ the resources available, including manpower and expertise ■ the individual’s personal support systems and social networks ■ the reason for referral ■ the intervention contract. Once a referral is accepted, a more focused assessment is carried out to determine the person’s needs, strengths, interests and goals. Effective assessment leads directly to setting measurable goals or defining expected outcomes of intervention and to choice of intervention methods. It also establishes a baseline from which change can be measured. There may be no clear division between assessment and intervention in occupational therapy, where people are often assessed through observation of their participation in activities, which also have therapeutic value. (This is explained in more detail in the Chapter 5.) However, at some stage the therapist and the person they are working with begin to formulate problems, establish goals and agree on a plan of action. People are complex and it is usually possible to formulate their problems or needs in different ways, each of which will indicate an alternative approach to intervention. For example, a woman with a diagnosis of severe depression may be experiencing low mood, suicidal ideation, fatigue, poor self-esteem, delusions about her body, loss of appetite, insomnia and agitation. If her problem is formulated as a biochemical imbalance, the main focus of intervention will be to remediate this with antidepressant medication. If her problem is seen as the result of faulty thinking, the object of intervention will be to provide her with cognitive strategies for managing her condition. The occupational therapist is more likely to formulate her problem in terms of activity limitation and restricted participation, so that intervention will focus on achieving a more healthy range and balance of activities. The occupational therapist formulates the desired outcomes of intervention as goals (the individual will return to work), problems (the individual is too tired to get up in time for work) or needs (the individual needs to re-establish a normal sleep pattern). The way that problems are formulated influences the actions that are taken to achieve desired outcomes. In person-centred practice, the therapist and the person they are working with negotiate and agree the goals of intervention. Goals are the desired outcomes of the intervention. An actual outcome is the extent to which goals have been met following the intervention. Outcome goals can be expressed on different levels (Creek 2003): ■ Developing skills, such as learning to read ■ Carrying out tasks, such as putting aside the money to buy a newspaper every day ■ Engaging in activities, for example, walking to the shop to buy a newspaper every morning ■ Performing occupations, for example, keeping abreast of current affairs by reading the newspaper every day ■ Participating in life situations, for example, reading the newspaper every morning and discussing the news with a group of friends. A review date is set at the time when the goals of intervention are set. This is the date when measurement occurs. The more precisely a goal is defined the easier it will be to measure when it has been reached. An individual may want to achieve several outcomes, in which case it will be necessary to decide which ones to work on first. When an individual is too unwell to express a view about what the priority should be, the therapist has to make a decision about initial goals. If possible, this should be discussed with colleagues, family and carers. Once problems have been identified and priorities agreed, it is necessary to plan what approach to use and what actions are needed to achieve the desired outcomes. The preliminary action plan should be formulated by the therapist and the individual together, depending on the person’s capacity for contributing to the process at this stage. Other significant people, such as carers, may also be involved. The action plan includes the goals of intervention or desired outcomes, methods to be used, an individual programme and a list of the people who need to be informed about the programme. Occupational therapy interventions are usually designed to meet several goals or achieve several outcomes. In person-centred practice, each programme of intervention is highly individualized. Factors taken into account in drawing up the intervention plan include: ■ the person’s needs, values and preferences ■ the person’s circumstances and environments, including social circumstances ■ the therapist’s style of working and preferences ■ the quality of the relationship between the therapist and the person they are working with ■ the intervention setting, including resources available and what is expected of the therapist ■ the evidence base for intervention ■ local and national policies and standards. Most occupational therapy interventions involve partnership working with other professionals, carers, community workers or volunteers. As far as possible, the therapist negotiates what action to take and how the results can be interpreted so that the person involved in occupational therapy shares control over the process (Creek 2003). Occupational therapy intervention usually involves engaging individuals in activity. The therapist may engage in activity with them or they may discuss activities that individuals carry out elsewhere. For example, a person may attend a cookery group run by the therapist or decide to join a cookery class at their local college. There is an element of risk in all occupational therapy interventions and respecting an individual’s choices can seem particularly alarming, especially for the inexperienced therapist. Assessing and managing risk is an essential aspect of intervention (see Ch. 5 for further discussion of risk assessment). The occupational therapist remains responsible for the people they work with when they delegate interventions to others, such as students or support workers. This includes ensuring that they only delegate tasks to those who are competent to carry out the procedures and provide sufficient direction or supervision (Creek 2003). An individual’s progress is continually monitored, both during intervention sessions and over time, in order to measure progress towards agreed goals and ensure that the intervention is being effective. Collaboratively, the therapist discusses and agrees modifications to the programme in response to assessment findings. Minor changes can be agreed without having to organize a full review or alter the action plan. Throughout the process of intervention, a close liaison is maintained with other disciplines involved so that any changes or problems can be shared. If the setting allows for a long period of intervention, regular reviews are held to evaluate the need for more radical programme changes. Clear and regular records of intervention sessions are kept to assist in the review process (see Ch. 7). Review meetings serve several purposes: ■ They give everyone involved in intervention an update on the person’s progress. Review meetings may be multidisciplinary, in which case everyone has a chance to discuss the person’s progress, they may be within the occupational therapy team, or they may be between a single therapist and the individual ■ They provide opportunities to set new short-term goals and to adjust intermediate and long-term goals in the light of new information or changes in the individual’s circumstances. Change is measured by comparing the results of assessment following intervention with the baseline assessment. There are four possible results of intervention: ■ the expected outcome is achieved ■ the outcome falls short of what was expected ■ the outcome is better than expected ■ the individual’s performance is worse than before the intervention. If the expected outcome has been achieved, the therapist and the individual involved may set new goals or, if they feel that enough has been done, the discharge procedure may be started. If goals have been partially met, then the intervention programme may be upgraded. If goals have not been met or the individual’s performance has deteriorated, then goal setting and action planning may have to be revisited. Planning for the end of an occupational therapy intervention should take place from the moment a referral is received or the therapist first starts working with an individual. If a person has been in hospital, or other place of residential care, discharge is planned so that their resettlement takes place as smoothly as possible. Ideally, everyone involved recognizes when goals have been reached or outcomes achieved, and agrees on the best time for the intervention to end. However, it is not always possible to reach agreement between an individual, the multidisciplinary team and any care-givers, so compromises have to be made. This may involve some form of follow-up so that an individual does not experience the termination as too abrupt. Reviewing and evaluating interventions and services is a way of safeguarding standards and ensuring that services are fit for purpose. Evaluation is essential to demonstrate the effectiveness of intervention for the person involved, the therapist, the referring agent and other interested parties. Evaluation should be a part of the whole occupational therapy process, through self-appraisal, professional supervision, peer review and feedback from service users. Formal evaluation of a particular aspect of the service, such as a group, or of the service as a whole may be carried out at intervals in the form of an audit. Clinical audit is discussed in more detail in Ch. 7. Evaluation of services should be carried out by occupational therapists themselves against their own standards of performance. Such evaluation may lead to: changes in skill mix in a service; a request for improved resources; restructuring the service, or a complete change of focus, such as relocating staff from specialist community teams to primary care. In Ch. 3, a frame of reference was defined as: ‘a collection of ideas or theories that provide a coherent conceptual foundation for practice’ (Creek 2003, p. 53). As the knowledge base of occupational therapy has expanded, theories have been organized into an increasing number of frames of reference, approaches and models. In 1946, a textbook on the theory of occupational therapy (Haworth and MacDonald 1946) described one approach to therapy (rehabilitation) and offered one chapter on occupational therapy in the treatment of mental disorders, which focused on engaging patients in activities to improve or maintain health. In 2008, the 4th edition of this book referred to eight frames of reference used in occupational therapy for mental health: psychodynamic; human developmental; cognitive behavioural; occupational behaviour; health promotion; cognitive; rehabilitative and occupational performance (Creek 2008). New developments in theory and practice may result in further frames of reference being developed in the future, such as a community development frame of reference. A frame of reference delineates the field and the theoretical base for practice while a model gives more precise directions for putting theory into practice. Some models for practice are associated with more than one frame of reference. For example, Cole’s seven steps, which are a model for group leadership, draw on elements of the person-centred, the cognitive behavioural and the developmental frames of reference (Cole 2012). Other models draw their theory from a single frame of reference: for example, adaptation through occupation (Reed and Sanderson 1992) developed within the occupational behaviour frame of reference. Table 4-1 shows eight frames of reference and examples of models that are associated with them. TABLE 4-1 Frames of Reference Used in Mental Health Occupational Therapy Note: Original references have been given to highlight the sequence of development of the models for practice. There have been more recent developments and publications on all these models because they are still in use by occupational therapists.

Approaches to Practice

INTRODUCTION

CONTENT OF PRACTICE

Goals and Outcomes

Populations Served

Statutory Services

The Social Field

Legitimate Tools

Therapeutic Use of Self

Activities as Therapy

Environment

Core Skills

Thinking Skills

Professional Artistry

THE OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY PROCESS

Referral

Information Gathering

Assessment

Problem Formulation

Goal Setting

Action Planning

Action

On-Going Assessment and Revision of Action

Outcome Measurement

End of Intervention

Review

FRAMES OF REFERENCE

Frame of Reference

Example of a Model for Practice

Reference

Psychodynamic

Occupational therapy as a communication process

Fidler and Fidler 1963

Human developmental

Recapitulation of ontogenesis

Mosey 1968

Cognitive behavioural

Cognitive therapy

Beck 1976

Occupational behaviour

Model of human occupation (MOHO)

Kielhofner and Burke 1980

Health promotion

Transtheoretical model

Prochaska and DiClemente 1983

Cognitive

Functional information-processing model (cognitive disability)

Allen 1985

Rehabilitative

Recovery

Deegan 1988

Occupational performance

Canadian model of occupational performance and engagement (CMOP-E)

Townsend and Polatajko 2007

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree