Epilepsies with Tonic-Clonic Seizures

Generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCSs), also known as grand mal seizures, represent the prototypical epileptic seizures. However, GTCSs do not constitute a homogeneous group, and they occur in a variety of clinical circumstances. Occasional seizures, especially febrile convulsions, are usually GTCSs (see Chapter 14). When GTCSs are a manifestation of a chronic seizure disorder, they are often associated with other forms of attacks of either a generalized or a focal nature. For example, GTCSs may precede, accompany, or follow typical absences in early childhood or adolescence, and they are often associated with myoclonias. In other patients, they alternate with partial seizures. In many patients, however, GTCSs are the only type of seizure, although the exact frequency of such an occurrence is poorly known; it probably varies with the origin of the patients and the investigations performed.

Large epidemiologic studies (Ross and Peckham, 1983; Ross et al., 1980) have indicated a high frequency of grand mal epilepsy. However, the classification of seizures in such studies is often debatable because of the manner in which data are collected. O’Donohoe (1985) states that 70% of all seizures in childhood are GTCSs that occur either as the sole type of attack or in association with partial seizures or other fits. On the other hand, the incidence of GTCSs that occurs in isolation and has no association with clinical and/or electroencephalographic (EEG) evidence of a local lesion seems much lower. Gastaut et al. (1973b) reported that GTCSs comprise 9.5% of the classifiable epilepsies of childhood. Oller-Daurella and Oller (1992) found only 80 cases that were characterized solely by GTCSs among the 392 children with generalized seizures in the 1,847 cases of childhood epilepsy that they studied, for an incidence of 5.4%. These figures may, however, be too low as they emanate from specialized centers to which patients with “ordinary” seizures often are not referred. The incidence also depends on age; GTCSs are uncommon before 3 years of age, although they do occur (Aicardi and Chevrie, 1982b). In this age-group, atypical seizures that are often difficult to classify are much more common than grand mal attacks (Chevrie and Aicardi, 1977).

From a pathophysiologic viewpoint, GTCSs can be divided into the following three subgroups:

GTCSs may be apparently generalized from the start. Such primarily GTCSs are often a manifestation of idiopathic epilepsy. Myoclonic jerks that immediately precede the seizure are common in this form.

GTCSs may represent the secondary generalization of a partial seizure; this is more common with a simple partial seizure than with a complex partial one. Such secondarily generalized seizures can be of two varieties. In some cases, the initial partial seizure is manifested clinically by localized motor, sensory, or other phenomena. This initial partial seizure traditionally was referred to as the “aura” of the GTCSs. In other cases, the seizure appears generalized from the outset, but EEG recordings demonstrate that an initial focal discharge occurs that remains clinically inapparent either because it involves a “silent” area of the brain or because the memory of any subjective manifestation experienced by the patient is erased by retrograde ictal amnesia. When no ictal records are available, those seizures that occur in patients who have a stable interictal EEG focus are commonly considered to be secondarily generalized. Such focal paroxysmal activity is found in the EEG recordings of 20% to 40% of patients with tonic-clonic seizures (Kreindler et al., 1969). Secondarily generalized attacks may alternate with partial attacks, or they may represent the only ictal manifestation. Only seizures that are not associated with clinical partial seizures are discussed in this chapter. Patients in whom both partial and generalized seizures occur are discussed in Chapter 10.

Finally, GTCSs may be the expression of an epilepsy with multiple independent foci. In this case, they are almost always associated with other seizure types such as absences, tonic seizures, or partial seizures; they also are often atypical with a less regular course and less regular EEG recordings (Chapter 10).

SEIZURE PHENOMENA

Clinical Manifestations

The core of the attack consists of a stereotyped series of motor and autonomic manifestations that are associated with an immediate loss of consciousness (Gastaut and Broughton, 1972). The tonic phase comprises a sharp, sustained contraction of muscles that produces a fall to the ground that is often injurious when the patient is standing or sitting. The patient lies rigidly in an extensor posture that is often preceded by a transient stage of flexion. Opisthotonus is unusual. The tonic contractions of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles inhibit respiration, and cyanosis occurs. After 10 to 30 seconds, the tonic phase gives way to clonic jerks, which often follow a brief intermediate period of vibratory tremor (Gastaut et al., 1974a). The jerks are bilateral and symmetric. The jerks progressively slow as the seizure proceeds, while, at the same time, becoming increasingly violent. The jerks may be accompanied by brief expiratory grunts, as diaphragmatic contractions force air against the closed glottis. Froth appears at the mouth, and the tongue may be bitten during this stage. After 30 to 60 seconds, muscular relaxation occurs. Careful observation, however, reveals that a second tonic contraction, lasting only a few seconds in most cases, usually takes place before relaxation. During this second tonic phase, the muscle tone is preferentially increased in the cephalic muscles, and tongue biting is common (Gastaut and Broughton, 1972). The patient remains unconscious for variable durations. Respiration is stertorous, and pallor replaces cyanosis. Urinary incontinence occurs in one-third of these patients, but fecal incontinence is uncommon (Browne, 1983b; Gastaut et al., 1974a). The autonomic phenomena may include tachycardia, increased blood pressure, flushing, salivation, miosis, and increased bronchial secretions (Gastaut and Broughton, 1972). Some GTCSs are immediately preceded by a series of myoclonic jerks that, at times, are so prominent that the term clonic-tonic-clonic seizure has been proposed for such cases (Delgado-Escueta et al., 1983a), and an initial cry is common.

Atypical GTCSs are extremely common in children. The tonic phase may be much longer than the clonic stage, which may be limited to a few jerks. Both the tonic contraction and the clonic stage may be asymmetric. In addition, asynchrony of up to several seconds between the two sides of the body is not unusual (Gastaut et al., 1974a), but clinical detection may be difficult. These seizures are usually much less violent in young children than they are in adults, and those injuries that are caused by muscular contractions during an attack, such as compression fractures of vertebrae, are generally not observed before late adolescence.

Electroencephalographic Manifestations

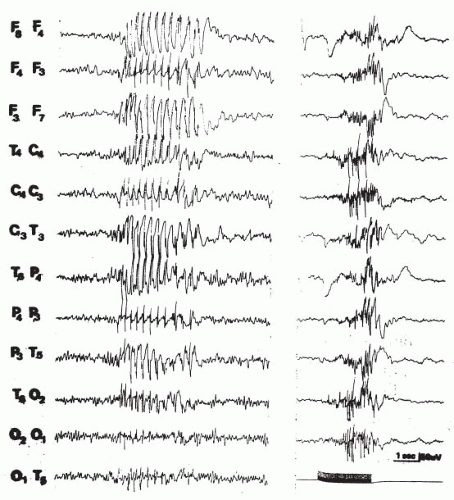

The tonic phase of a GTCS is characterized by a rhythm of 10 Hz that increases rapidly in amplitude; it has also been called the epileptic recruiting rhythm (Gastaut and Tassinari, 1975a; Gastaut and Broughton, 1972). Toward the end of the tonic phase, this rhythm tends to become discontinuous. During the clonic phase, bursts of 10-Hz rhythms become separated by intervals of inactive tracing or by slow waves. The bursts are synchronous with the jerks, which may be regarded as an interrupted tonus (Gastaut and Broughton, 1972). The bursts of fast rhythm become further apart and more brief. At the end of a seizure, single spikes are common, and they may be followed by a slow wave, forming atypical spike-wave formations. A phase of inactive flat tracing, the phase of cortical exhaustion, follows the clonic stage. Although the ictal phenomena are generally bilateral and synchronous, a significant degree of asymmetry is not uncommon in GTCSs in children.

The physiologic basis of GTCSs has been studied in animal models. Only pentylenetetrazol (Metrazol) and megimide (Browne, 1983b; Gastaut and Broughton, 1972) produce a sequence of events comparable to that observed in human primary tonic-clonic seizures. Studies in animals have demonstrated that subcortical structures, especially the midbrain reticular formation, play a key role in the initiation of megimide-induced seizures. High-voltage fast activity that is recorded in the midbrain reticular formation is synchronous with the myoclonic jerks, and it is continuous throughout the tonic phase. The origin of GTCSs in humans, however, remains controversial. Most investigators postulate a diffuse thalamocortical hyperirritability (Gloor et al., 1990; Gloor, 1983). Bancaud et al. (1974) showed that the stimulation of the mesial orbitofrontal cortex in epileptic persons could induce either GTCSs or generalized spike-wave activity similar to that recorded in typical absences, depending on the frequency of stimulation. A cortical origin of GTCSs is therefore possible, even though the subcortical structures undoubtedly play an important

role in the elaboration of the discharge (Gloor, 1979).

role in the elaboration of the discharge (Gloor, 1979).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of GTCSs is discussed in Chapter 21. The most common diagnostic problem is that of syncopal attacks. This is especially true for children in whom the tonic phase of GTCSs often predominates over the clonic phase. Seizures in syncope are mainly tonic fits, although, not uncommonly, a few jerks may follow the tonic phase. Opisthotonus is much more common in syncopal attacks than in grand mal seizures. Downward deviation of gaze is another important feature (Stephenson, 1990). Provocation of the fits by emotional stimuli (e.g., pain, anger), no matter how the fits are described, is a strong argument for syncope. Urination can occur during syncopes, and the tip of the tongue may be bitten as a result of the patient’s fall. Lateral tongue biting or biting of the inner cheek, however, is also characteristic of GTCSs.

Hysterical attacks or pseudoseizures are uncommon in young children, but they do occur relatively frequently in adolescents (Chapter 21). Distinguishing other varieties of epileptic seizures from GTCSs may be difficult. In general, the label “GTCSs” tends to be applied loosely to a wide variety of epileptic seizures of different significance. For example, a number of partial seizures have generalized autonomic and some bilateral motor manifestations that are all too often regarded as sufficient evidence for GTCSs, resulting in misdiagnoses. Distinguishing tonic seizures (see Chapter 4) from grand mal attacks may also be difficult. However, the overall clinical picture and the association with other types of fits should permit diagnosis. Clearly, the management and prognosis of such cases differ from those in GTCSs.

SYNDROMES FEATURING GENERALIZED TONIC-CLONIC SEIZURES AS THE PREDOMINANT TYPE OF ATTACK

GTCSs are a common manifestation of epilepsy in children older than 2 to 4 years and in adolescents. They may be the only or the predominant type of seizures in some epilepsy syndromes in this age-group, although, in many patients, they are not the most characteristic type; they are, however, of relatively little value in the diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome, which depends more on the characterization of the associated seizures. This section successively considers the syndrome of idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE) with GTCSs in adolescents, the less well-defined spectrum of generalized convulsive epilepsy in childhood, and the syndrome of generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) and then briefly reviews the significance of secondarily generalized seizures.

Idiopathic, or Primary, Generalized Epilepsy of Adolescents with Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures

Epilepsy syndromes that feature prominent GTCSs are also expressed with additional seizures in many patients (Fig. 9.1). The most common are those with myoclonic attacks and typical absences. The syndromes that include these types of attacks are studied in Chapters 6 (juvenile myoclonic epilepsy [JME]) and 8 (juvenile absences).

Epilepsies with exclusive or predominant GTCSs have also been classified into the following three categories according to their relationship to the sleepwaking cycle (Wolf, 1992a; Janz, 1974): awakening grand mal; grand mal of sleep; and diffuse grand mal,

which occurs in both sleep and wakefulness. In this type of classification, the only relatively well-defined syndrome (see discussion below) is that of awakening grand mal (Wolf, 1992a).

which occurs in both sleep and wakefulness. In this type of classification, the only relatively well-defined syndrome (see discussion below) is that of awakening grand mal (Wolf, 1992a).

The syndrome may have its onset as early as 8 or 9 years of age, but, most commonly, it appears during the teens. More than two-thirds of patients have their first attack before 19 years of age, and the peak frequency of onset is between 14 and 16 years. Gastaut et al. (1973b) found that the affected females outnumbered affected males (54% vs. 46%) and that, in one-third of the female patients, the onset of seizures coincided temporally with the first menstruation.

The seizures typically are of the primary generalized type, and they occur most often in the half hour following awakening. The term awakening grand mal stricto sensu applies only to cases in which all of the seizures occur with this schedule. According to Janz (1969), the diagnosis depends on the occurrence of five GTCSs on awakening without other types or schedules of attacks. However, the occurrence of some seizures during sleep (Wolf, 1992a; Janz, 1991; Tsuboi, 1977b) or in the evening when the patient is relaxing (Janz, 1991; Touchon, 1982) is possible. The provocation of the seizures by sleep deprivation is common (Touchon, 1982; Gastaut et al., 1973b). The precipitating role of alcohol ingestion has also been stressed, but separating its role from that of sleep deprivation is difficult because both are strongly interrelated. The latter factor is, however, considered more important. Another precipitating factor is “naturally” occurring intermittent photic stimulation, which, in Gastaut’s experience, induced seizures in 13% of patients, which is much lower than the EEG paroxysms induced by flickering light in 29% of the patients in the EEG laboratory. Natural photic stimulation may include such stimuli as riding a car along a road lined with trees or the reflection of the sun on water. Television watching, electronic games, and the flashing lights of dance clubs are much more common precipitants (see Chapter 17). The interictal EEG recording is normal in most patients (Wolf, 1992a). GTCSs are generally infrequent in primary generalized epilepsy, with 37% to 70% of patients having less than one seizure a year. Seizures that occur more often than once a week are unusual (12% of Gastaut’s patients).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree