3

Epileptic and Nonepileptic Paroxysmal Events in Childhood

Paroxysmal events (epileptic and nonepileptic) are commonly encountered in general pediatric and neurology practices. Epileptic events or seizures refer to a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain (1). Paroxysmal nonepileptic events (PNEs) also manifest as a transient occurrence of stereotyped or somewhat stereotyped clinical episodes, but they are not associated with paroxysmal, excessive cortical activity.

In children admitted to epilepsy units for long-term video-electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring, about 22% to 43% may receive the diagnosis of PNEs (2–4). This diagnosis is even more common in children who are neurologically impaired (4,5), as hyperkinetic movement disorders, spasticity, attention deficit, and staring are more prevalent complaints. Children with autism and developmental delay with or without cerebral palsy may represent a diagnostic challenge (3).

A detailed history and physical examination is helpful in clarifying the etiology of these episodes, but often this clinical differentiation is not an easy task and specific tests such as long term video-EEG or polysomnograms are needed, in order to arrive at a specific diagnosis (6,7). Furthermore, epileptic and nonepileptic events may coexist in the same patient, making diagnosis even more challenging.

The use of video-EEG can distinguish the nature of these paroxysmal events in most cases (4,8,9).

Epileptic and nonepileptic events share many common characteristics that can make differentiation difficult (Table 3.1), even for the more experienced neurologist. Clinicians have to rely often on the history provided by parents, as the events are not directly witnessed during the short clinic visit.

TABLE 3.1 Common Features of Epileptic and Nonepileptic Events

Intermittent, periodic occurrence Sudden change in what is considered normal behavior for the child Daytime and nighttime occurrence Stereotyped or somewhat stereotyped symptomatology Usually short in duration Cause of concern for parents |

Identification and accurate classification of the event is extremely important, as treatment is based on the presumptive etiology. Many children referred to tertiary epilepsy centers are misdiagnosed as epileptic and placed unnecessarily on antiepileptic medication (2,4,10). The incorrect diagnosis of epilepsy can add significant stress to the family and impose unnecessary limitations on the child.

The clinical manifestations of PNEs are highly variable. These may include hypermotor features (paroxysmal movement disorders, shuddering attacks, benign sleep myoclonus), behavioral or motor arrest (staring, apnea), alteration in consciousness (syncope, breath-holding events), sensory phenomena (hallucinations, migraine), mixed manifestations (syncope with convulsive features), or other symptoms (cyclic vomiting).

Some PNEs may occur exclusively during wakefulness (psychogenic nonepileptic seizures [PNESs], shuddering attacks) and others take place during sleep (parasomnias).

Age of presentation is an important factor in the differential diagnosis, as certain PNEs are prevalent in specific age groups, for example, “benign sleep myoclonus” is observed in neonates and young infants and PNES occurs mainly in older children and adolescents.

As a result of this highly variable clinical presentation and symptomatology, it is easy to perceive the difficulties in making an accurate diagnosis during the first clinic visit. Short periods of inattention in children with attention deficit disorder (ADD) or autism can be confused with absence seizures, and parasomnias may be difficult to distinguish from seizures of frontal lobe origin. On the other hand, epileptic syndromes such as “benign occipital epilepsy” presenting with episodes of vomiting or headaches can be misdiagnosed as gastroesophageal reflux disorder or migraine.

This chapter presents a review of some of the most frequent nonepileptic events encountered in clinical practice. The clinical characteristics and features that may help in correct identification of the episodes are described.

EVENTS WITH MOTOR MANIFESTATIONS AS THE MAIN CLINICAL FEATURE

Benign Neonatal Sleep Myoclonus

Benign neonatal sleep myoclonus (BNSM) is a benign condition characterized by repetitive, usually synchronous myoclonus involving the extremities. The jerks occur exclusively during sleep and remit when the child is aroused. This condition usually starts in the first 2 weeks of life and resolves spontaneously by 3 months of age with no neurological sequelae (11).

It is important to differentiate this benign condition, as BNSM can be confused with neonatal seizures and the patients placed on anticonvulsants (18). The diagnosis should be made by history and careful clinical observation. The occurrence of myoclonus during sleep and its disappearance by arousal in a neonate should raise the suspicion for this benign condition.

Jitteriness

Jitteriness is one of the most common involuntary movements encountered in full-term babies. Jitteriness consists of rhythmic tremors of equal amplitude around a fixed axis. The etiology of the condition is not clearly defined in the majority of cases, but it has been associated with electrolyte abnormalities or maternal drug use. Jitteriness is observed very early in the neonatal period and diminishes markedly by the second week of life.

The prevalence can be about 44% in large urban centers (19). There is a positive association of maternal marijuana and possibly cocaine use with neonatal jitteriness (19,20). These infants also demonstrate visual inattention and irritability compared with nonjittery infants. The jittery movements can be differentiated from seizures because they are commonly stimulus sensitive and may terminate with passive flexion of the baby. Rarely, jitteriness can occur immediately after the neonatal period (21).

Benign Myoclonus of Early Infancy

Benign myoclonus of early infancy (BMEI) was described for the first time in 1976 by Fejerman (22,23). The first descriptions included children with events resembling infantile spasms without abnormalities in the EEG. The clinical entity consisted of jerks of the neck and upper limbs leading to flexion or rotation of the head and abduction of limbs and no changes in consciousness. Patients with brief tonic flexion of the limbs, shuddering, and loss of tone or negative myoclonus have also been included as part of the syndrome. Age of presentation is usually between 3 and 8 months.

Newer attempts to redefine the clinical spectrum of the syndrome include different types of motor phenomena such as myoclonic jerks, spasms and brief tonic contractions, shuddering, and atonia.

BMEI can be confused with “epileptic” infantile spasms. For most cases, this differentiation is not difficult. There is lack of hypsarrhythmia or EEG abnormalities in BMEI in contrast to epileptic infantile spasms, which often have a characteristic EEG pattern. Also in contrast to infantile spasms, development in BMEI is normal, and the events subside by 6 to 30 months of age (24).

Shuddering Attacks

Shuddering attacks are benign nonepileptic events of infancy consisting of rapid “shivering” of the shoulders, head, and occasionally the trunk.

It is believed that prevalence of events is low, but in a large series of children with nonepileptic events, shuddering attacks represented 7% of all cases (3). The pathophysiology is not understood, but a relationship with essential tremor has been postulated (26), and propranolol has been used as treatment (27). Further studies did not find an association between essential tremor and shuddering attacks (28).

The distinction between seizures, especially brief generalized and myoclonic seizures should not represent a diagnostic challenge. Shuddering attacks have precipitating factors and there is no alteration in consciousness or postictal state.

Stereotypies

Similar to tics, stereotypies are repetitive, purposeless, ritualistic movements that can be exacerbated by stress, excitement, or even boredom. Stereotypies usually affect the body and arms (arm flapping, body rocking). They can occur in normal children as well as in children with autism spectrum disorder (29) and syndromes associated with mental retardation.

The presence of precipitating factors and the fact that they can stop if the child is distracted can help in differentiating these movements from epileptic events.

Tics

Tic disorder is another common condition affecting about 1% of the population. Tics are sudden, rapid, brief movements (motor tics) or sounds (vocal tics). Tics may be simple or complex, involving different muscle groups or presenting with a complex sequence of movements. On occasions, tics can cause self-injury.

Tics are classified as transient tic disorder (duration of symptoms lasting less than 1 year) or chronic motor or vocal tics (lasting more than 1 year). Tourette syndrome is the most common cause of tics and includes motor and one or more vocal tics, although not necessarily concurrent. Tics must occur intermittently for more than 1 year (30). Children diagnosed with Tourette may face different comorbidities, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and behavioral difficulties (31).

The motor manifestations of tics are florid. The movements usually start on the face (blinking or gestures) and later they may involve the trunk and extremities. The nature of movements can be tonic, clonic, or even myoclonic, creating diagnostic confusion.

Some features are helpful in making the distinction between tics and epileptic events. Tics are often preceded by a sensation of discomfort, which is alleviated after execution of the tic (32). Patients can also suppress their tics. Tics can occur multiple times a day and become more frequent during periods of stress, boredom, or excitement.

Treatment with behavioral therapy or habit reversal is promising (34). Medications are used in selected cases, especially if tics are causing problems with self-esteem or injury.

Paroxysmal Dyskinesias

The paroxysmal dyskinesias as a group can, at times, be confused with epileptic events, as they share common features including the following:

1. Paroxysmal, intermittent episodes of involuntary movements

2. Events may be preceded by premonitory symptoms or “auras”

3. Symptoms may respond to antiepileptic medications

In contrast to epilepsy, affected children do not have alteration in consciousness during the attacks and the EEG is normal.

The paroxysmal dyskinesias can be classified by the circumstances in which they occur as follows:

Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD), typically affects children from middle childhood to early adolescence. The etiology may be idiopathic or secondary to other neurological conditions, such as stroke or multiple sclerosis. PKD is characterized by involuntary movements (usually dystonia chorea or ballismus). The attacks are short in duration and they are precipitated by movement. There is no loss of consciousness during the episodes, and generally patients respond well to antiepileptic drug treatment (35,36). Premonitory symptoms, usually abnormal gastric sensations, are reported by patients. In some pedigrees, PKD has been associated with infantile convulsions (37).

Paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia (PNKD) is a disorder of early childhood, but can manifest in the early 20s. The attacks may be longer than the episodes observed in PKD, lasting hours or days (38), and do not have to be associated with movement. Problems with speech have also been reported at the time of the attack, but there are no changes in the level of consciousness. Patients may respond better to clonazepam than to sodium channel blockers (38). Paroxysmal exertion-induced dyskinesia is a movement disorder triggered by prolonged exercise (39) and affects mainly the legs, with attacks lasting about 5 to 30 minutes.

Paroxysmal hypnogenic dyskinesia consists of attacks of chorea or dystonia occurring in non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. The frequency is variable and duration is usually less than 1 minute. Frontal lobe seizures, especially “autosomal dominant frontal lobe epilepsy” may present with similar clinical features (40,41), and many cases of paroxysmal hypnogenic dyskinesias may actually represent epileptic events. Distinction between a true movement disorder and epilepsy may be difficult in those cases, as frontal lobe seizures may lack an ictal EEG correlate and the interpretation is difficult, due to excessive movement artifact. A high index of suspicion for seizures is recommended for nocturnal dystonic events, especially if episodes are stereotyped in nature.

Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures

PNESs are paroxysmal events, involving clear changes in behavior or consciousness, similar to epileptic seizures, but without associated abnormal cortical discharges. The prevalence of PNES is estimated between 2 and 33 per 100,000 (42) and comprises about 20% to 30% of the patients referred for diagnostic video-EEG monitoring (43).

PNES can be encountered in young children, but it is more prevalent in adolescents (43). There also appears to be a female predominance in the latter group, whereas in younger patients, boys can be more commonly affected.

There are signs that can help in differentiating nonepileptic from epileptic seizures (44):

1. High frequency of seizures

2. Resistance to antiepileptic drugs

3. Specific triggers

4. Occurrence in the presence of an audience or in a physician’s office

5. Multiple complaints, including fibromyalgia and chronic pain

There are also specific features of the episode that can help in distinguishing PNESs from epileptic seizures. These features are irregular and asynchronous motor phenomena, waxing and waning symptoms, pelvic thrusting, weeping, preservation of awareness with generalized motor activity, or eye closure during the events.

Clinical manifestations of PNES may be different in the pediatric population. Quiet unresponsiveness or “catatonic” state is a common manifestation in children (10,43). Tremor is also a common feature (10,45), in addition to negative emotions (45), eye closure or opening, and events with minor motor activity. Pelvic thrusting and major motor activity are more prevalent in adults (46).

Many children have associated psychiatric comorbidities including other conversion/mood disorders, anxiety and school refusal, along with psychosocial stressors, including physical and sexual abuse (47).

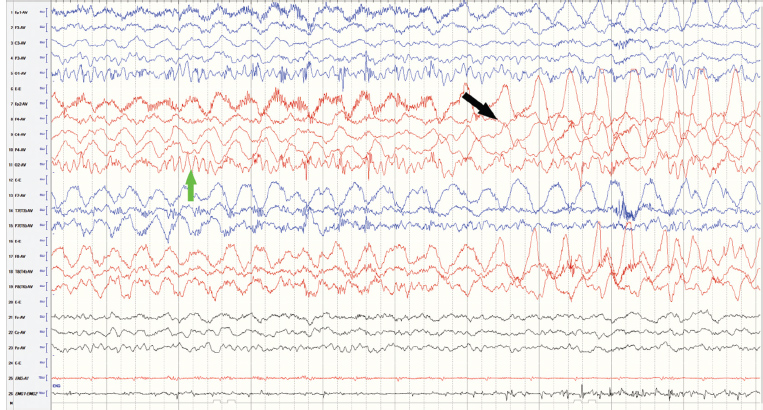

Video-EEG is an important tool in making an early diagnosis and therefore designing a treatment plan (Figure 3.1), which includes psychological support. The prognosis of PNES in children is more favorable (48).

Sandiffer Syndrome

Gastroesophageal reflux in infants can cause symptoms that are different from those in adults. The symptoms are variable and consist of crying, irritability, sleep difficulties, and back arching (49). Sandiffer syndrome is a more extreme posturing of the head and neck, manifesting as intermittent spells of opisthotonic posturing associated with reflux and hiatal hernia (50). The occurrence of the events during or after feedings is a clue to the diagnosis.

Hyperekplexia

Hyperekplexia is a disorder associated with an exaggerated startle response with delayed habituation, elicited at times by minor auditory or tactile stimuli (nose tapping or air blowing on the face), in association with other symptoms such as hyperalert gaze, marked stiffness, violent rhythmic jerks, and breath-holding episodes (51). This is a relatively benign disorder, but in severe cases, the symptoms can cause apnea or interfere with feedings. The condition can be easily mistaken for epilepsy, as nocturnal myoclonus can be part of the clinical picture (52). In hyperekplexia, the EEG is normal and patients usually improve with clonazepam at doses of 0.1–0.2 mg/kg/day (53). This neurological condition can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Most mutations have been identified in the GLRA1 gene encoding the alpha 1 subunit of the glycine receptor (54,55).

FIGURE 3.1 Ten-year-old boy with typical PNES captured on video-EEG monitoring. EEG shows a clear posterior dominant rhythm (green arrow), despite movement artifact (black arrow). Clinical episode consisted of asymmetric shaking of extremities, associated with pelvic thrusting. Patient remained with eyes closed during the event. Average montage, amplitude 7 uV/mm, 10-seconds screen.

Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalogram; PNES, psychogenic nonepileptic seizures.

Self-Gratification Disorder

Self-gratification disorder or infantile masturbation is considered a variant of normal behavior and an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of seizures. Symptoms may include dystonic posturing, sweating, grunting, and rocking (56). This is a benign and self-limited behavior that often disappears by 2 years of age (57).

EVENTS WITH SENSORY MANIFESTATIONS AS THE MAIN CLINICAL FEATURE

Migraine

Migraines, especially when preceded by an aura, can be mistaken for seizures. This is not surprising, as auras represent a focal cortical and/or brainstem dysfunction. Occasionally, migraine auras may not be followed by a headache, creating even more confusion.

There are certain characteristics that are helpful in distinguishing migraines from epileptic events. In migraines, the aura develops gradually for over more than 4 minutes, and two or more symptoms occur in succession. Headaches follow the aura with a symptom-free period of about 60 minutes (60). A positive family history of migraine is usually encountered.

Seizures of occipital origin may manifest with visual symptomatology, but circular shapes appear to predominate and the duration of symptoms is short, from 5 to 30 seconds (61). The postictal headache may be diffuse rather than unilateral (62).

Panic Attacks

Panic attacks are primarily a psychiatric disorder, consisting of recurrent episodes of a sudden, unpredictable overwhelming sensation of fear with a myriad of symptoms including dizziness, shortness of breath, nausea, depersonalization, and paresthesias. During the attack, fear of dying and autonomic symptoms, such as palpitations, are usually present. Patients may interpret typical symptoms of anxiety as dangerous, creating an exaggerated response.

Seizures can also manifest with anxiety or fear, especially seizures of temporal or even parietal lobe origin (63), at times making the differentiation between panic attacks and seizures more difficult. Both can occur spontaneously without warning, but ictal fear usually is brief, lasting a few seconds, in contrast to the prolonged duration of panic attacks, usually lasting minutes to hours (64).

Hallucinations

Hallucinations can occur in children and may be visual, auditory, or involve abnormal sensations. Hallucinations are not necessarily an indication of psychosis. They can be related to physical abuse or the use of psychotropic medications, and a detailed history becomes necessary. As mentioned earlier, hallucinations associated with seizures usually consist of simple forms, smells, or sounds, and they are of short duration. The events are also stereotyped and brief (seconds), only rarely persist longer (65).

EVENTS ASSOCIATED WITH CHANGES IN THE LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS OR ALERTNESS AS THE MAIN CLINICAL FEATURE

Staring Events

Staring spells are among the most common nonepileptic events observed in the pediatric population, making up to 15% of the patients referred for video-EEG monitoring (3). These events consist of vague facial expression, behavioral arrest, and fixed vision at one point. Children may not react to hand waving but the spell can be interrupted by stronger stimulation (3).

Breath-Holding Spells

Breath-holding spells (BHSs) are common pediatric conditions, which may occur in up to 27% of children (68,69). BHSs have a distinctive sequence of clinical features. There is a precipitating event, which is usually a mild trauma (commonly to the head) or provocation, resulting in crying. Subsequently, the child becomes silent during the expiratory phase, followed by color changes and loss of consciousness. The child may adopt an opisthotonic posture with upward eye deviation. After the event is over, the child may go to sleep. Two clinical types are recognized, based on skin color changes: cyanotic and pallid type. Cyanotic spells are more common with a ratio of 5:3 (70). Mixed types can also occur.

BHS presents in children between 6 months to 4 years of age, but younger and older patients have been reported. Median age of onset is between 6 and 12 months and the frequency of attacks is variable, with a median frequency of daily to weekly attacks (70). The attacks usually resolve by 3 to 4 years of age.

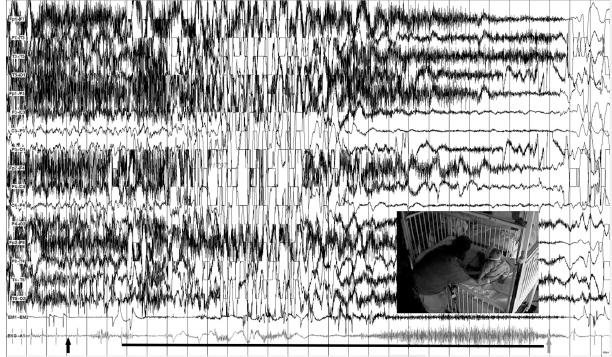

The pathophysiology is not completely understood, but involves a vagal mediated cardiac inhibition with significant bradycardia and asystole in the pallid type. This can be elicited by ocular compression, a procedure not recommended in current practice. The EEG during an attack shows generalized rhythmic slowing, followed by electrical attenuation and slowing again, with subsequent recovery of normal background activity (Figure 3.2) (71).

The cyanotic type may involve increased intrathoracic pressure due to a Valsalva maneuver with associated hypocapnia (72), but bradycardia can also be present, and the two types of spells can occur in a single patient, suggesting some common mechanisms. An autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with reduced penetrance is postulated (73).

The attacks usually are short, but frightening to parents. Longer events can produce “reflex anoxic seizures” and, in rare cases, status epilepticus. This may create confusion and BHS may be deemed to be epileptic in nature. The presence of precipitating factors, crying, and family history of similar events favors the diagnosis of BHS.

The treatment is directed mainly at reassurance about the benign nature of the events. The relationship between BHS, anemia, and effectiveness of iron therapy has been documented (74–76). Piracetam is another drug that showed to be safe and effective in controlling the spells (77,78). For patients with severe and frequent spells associated with seizures and prolonged asystole, cardiac pacemakers have been used (79).

FIGURE 3.2 Twenty-month-old boy with pallid breath-holding events. EEG demonstrates bradycardia (black arrow) after episode of crying, followed by prolonged, 20-seconds asystole (black line). EEG during that period shows generalized background slowing, followed by diffuse electrical suppression, associated with opisthotonic posturing of the child (inserted picture). After the event, heart rate returns to baseline (gray arrow). Longitudinal montage, amplitude 150 peak-to-peak, 30-seconds screen.

Syncope

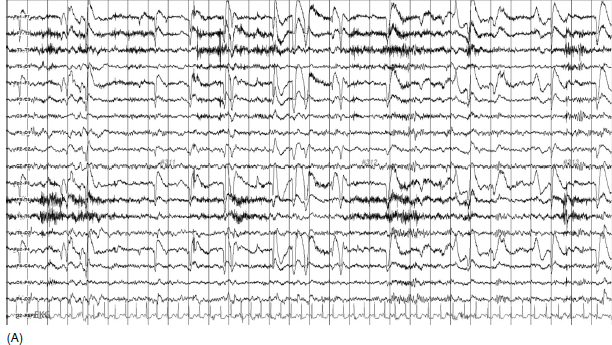

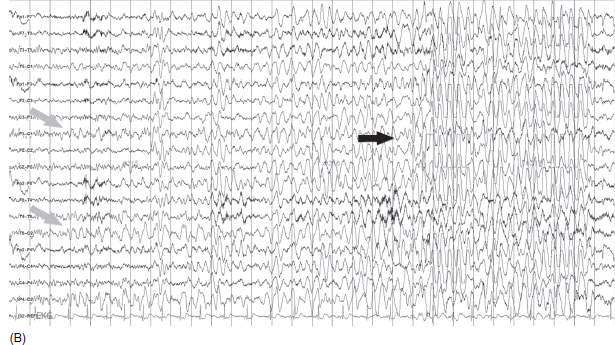

Syncope is a transient, abrupt loss of consciousness due to reduction in global cerebral perfusion. The most common cause of syncope is “vasovagal.” The true incidence of syncope is difficult to estimate due to variation in definition and underreporting in the general population (80). The median peak of the first syncope is around 15 years of age. Convulsive movements may be described in all types of syncope related to cerebral hypoxia and this may lead to a misdiagnosis of seizures (81). The EEG may show a pattern of slowing—attenuation–slowing or a “slow pattern” (Figure 3.3A–B). Stiffening and loss of consciousness develop during the slow phase and persist during the flat portion of the EEG. Myoclonic jerks occur when the EEG is slow (82). Clues in the differential diagnosis include precipitating factors, premonitory symptoms, and postictal events, such as tongue biting (83).

Situations commonly encountered in syncope are upright posture, emotionally induced events, and being in crowded places. The myoclonic jerks observed in syncopal episodes usually occur after loss of consciousness, whereas in epilepsy they appear at the same time (81). In syncope, motor manifestations are usually short-lived and postictal symptoms are not common.

If syncopal attacks occur during exercise or there is family history of heart disease or the presence of palpitations, an EKG should be ordered. A tilt table test is not necessary to make the diagnosis in most instances (81).

Figure 3.3B (A) Sixteen-year-old girl with history of vasovagal syncope. EEG during tilt table tests shows a normal background at the time patient was in the upright position. HR: 112. Bipolar montage, amplitude 7 uV/mm, 30-seconds screen. (B) This tracing is a continuation from the previous EEG on Figure 3.3A. EKG lead shows bradycardia (HR 60) immediately after patient was tilted. EEG demonstrates posterior slowing (gray arrows) followed by generalized higher-amplitude delta activity (black arrow). Patient had transient alteration of consciousness with associated upward eye deviation and pallor. Bipolar montage, amplitude 7 uV/mm, 30-seconds screen.

Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalogram; HR, heart rate.

Narcolepsy/Cataplexy

Cataplexy is a symptom associated with the diagnosis of narcolepsy. The disorder is characterized by muscle weakness triggered by emotions. There is a strong association with centrally mediated hypocretin (orexin) deficiency and with HLA-DQB1*0602 (84).

Children who present with a lack of responsiveness due to excessive sleepiness can be incorrectly diagnosed as having absence seizures, and cataplexy may be misdiagnosed as atonic or other types of epileptic attacks. Videotape recordings of the events can be helpful in clarifying the etiology of the episodes (85).

SLEEP-RELATED EVENTS

The parasomnias as a group are among the most frequent sleep disorders encountered in the pediatric population.

The most common parasomnias in children are the following:

Disorders of arousal (from NREM sleep): These events usually occur in the first half of the night, 1 to 2 hours after falling asleep. NREM sleep disorders are highly prevalent in children between the ages of 3 and 13 years and usually disappear by adolescence (86,87). Disorders of arousal may be mistaken for epileptic seizures and they include:

A. Sleepwalking. During sleepwalking, children may walk or wander around the room. They can go to the parent’s room or other places in the house. During the episode, children may be partially responsive.

B. Night terrors. During these events, the child may wake up and scream with a frightened look. Autonomic symptoms including tachycardia, pupillary dilatation, and sweating accompany the event.

C. Confusional arousals consist of partial awakenings in which the child remains confused and unresponsive, despite appearing to be awake.

Parasomnias associated with REM sleep: One of the common parasomnias that occur in REM sleep in children is nightmares. These are frightening dreams in which the child usually has a recollection of the event.

![]() Other parasomnias such as sleep enuresis can also create confusion, as parents may interpret these events as nighttime seizures, especially in children with epilepsy.

Other parasomnias such as sleep enuresis can also create confusion, as parents may interpret these events as nighttime seizures, especially in children with epilepsy.

![]() There are other paroxysmal events, such as cyclic vomiting, tremors, and rage attacks, which occur less frequently and can also be mistaken for epileptic events.

There are other paroxysmal events, such as cyclic vomiting, tremors, and rage attacks, which occur less frequently and can also be mistaken for epileptic events.

![]() As mentioned earlier, a clinical history with attention to detail is extremely important to formulate an appropriate diagnosis and differentiate between epileptic and nonepileptic events.

As mentioned earlier, a clinical history with attention to detail is extremely important to formulate an appropriate diagnosis and differentiate between epileptic and nonepileptic events.

![]() With the advent of new technology and widespread use of iPhones, these episodes can now be captured on digital videos, thus facilitating the diagnosis.

With the advent of new technology and widespread use of iPhones, these episodes can now be captured on digital videos, thus facilitating the diagnosis.

![]() There will always be cases in which this differentiation is not easy to accomplish, and other tests including video-EEG may be required in order to make a specific diagnosis.

There will always be cases in which this differentiation is not easy to accomplish, and other tests including video-EEG may be required in order to make a specific diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree