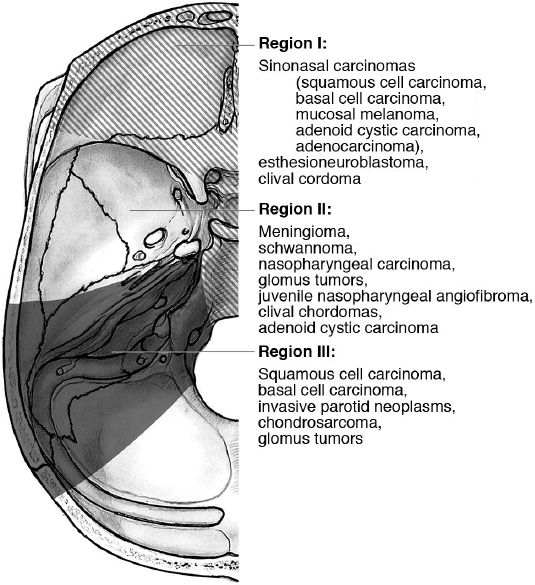

23 Extracranial Tumors Involving the Skull Base Skull base tumors comprise a variety of different pathologies whose management requires a multidisciplinary approach. Although intracranial tumors may initially present to the neurosurgeon, extracranial tumors that involve the skull base warrant particular attention, given their distinct pathology, clinical presentation, and treatment. Many patients with these tumors initially present to the otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeon, and a thorough understanding of these pathologies is essential to provide comprehensive treatment of the skull base. The traditional classification of intracranial skull base tumors is largely based on anatomic location (anterior, middle, posterior). In contrast, because skull base involvement with extracranial tumors occurs only in advanced disease or because of tumor growth through various skull base foramina, an appreciation of both tumor biology and anatomy is necessary in any classification scheme. One such system was developed by Irish et al1 in 1994. It divides the skull base into three main regions, and groups together extracranial tumors that may have similarities in both clinical presentation and treatment approach (Fig. 23.1). • Region I • Region II • Region III Collectively, sinonasal carcinomas are rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.556 cases per 100,000 per year in the United States. They account for 3 to 5% of head and neck malignancies. Because of the anatomic location of the paranasal sinuses, these tumors often do not present until they are at an advanced stage with soft tissue, orbital, or skull base involvement. Although a variety of histological sub-types exist, the majority of these carcinomas arise from the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, or ethmoid sinuses. Prognosis is generally poor, given the late stage at presentation. • All sinonasal tumors can grow indolently with very few nonspecific local symptoms. • Nasal obstruction, discharge, or epistaxis may be an initial clue to the presence of a malignancy. • Most tumors present at an advanced stage with skull base or orbital involvement. • Originally, a line connecting the medial canthus to the angle of the mandible was used to define the resectability of sinonasal malignancies. Tumors superior to this line were originally considered unresectable.5 • The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has defined a tumor, lymph node, metastasis (TNM) staging system for tumors arising from the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, or ethmoid sinus6: • Maxillary sinus (Table 23.1) • Nasal cavity and/or ethmoid sinus (Table 23.2) • Sinonasal carcinoma, lymph nodes involvement (Table 23.3) • Distant metastasis Table 23.1 Sinonasal Carcinoma—Tumor, Lymph Node, Metastasis (TNM) System: Maxillary Sinus Invasion6

Encompasses tumors that arise from the paranasal sinuses or anterior cranial fossa and can involve the orbit or other local structures

Encompasses tumors that arise from the paranasal sinuses or anterior cranial fossa and can involve the orbit or other local structures

Also includes tumors that arise/extend to the clivus and foramen magnum, as many of the these tumors share a similar biology and are often resected via an anterior approach

Also includes tumors that arise/extend to the clivus and foramen magnum, as many of the these tumors share a similar biology and are often resected via an anterior approach

Examples: See Fig. 23.1

Examples: See Fig. 23.1

Tumors that involve the infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossa with extension into the middle cranial fossa and lateral skull base

Tumors that involve the infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossa with extension into the middle cranial fossa and lateral skull base

Tumors that arise from around the ear, parotid, and temporal bone and extend intracranially to involve the middle or posterior cranial fossa

Tumors that arise from around the ear, parotid, and temporal bone and extend intracranially to involve the middle or posterior cranial fossa

Region I

Region I

Sinonasal Carcinoma2–4

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms may include epiphora (tearing), proptosis, diplopia, facial paresthesia, and headaches.

Symptoms may include epiphora (tearing), proptosis, diplopia, facial paresthesia, and headaches.

Staging

TX: tumor cannot be assessed

TX: tumor cannot be assessed

T0: no evidence of tumor

T0: no evidence of tumor

Tis: carcinoma in situ

Tis: carcinoma in situ

M0: no distant metastasis

M0: no distant metastasis

M1: distant metastasis

M1: distant metastasis

Stage | Description |

T1 | Tumor limited to maxillary sinus mucosa with no erosion or destruction of bone |

T2 | Tumor causing bone erosion or destruction including extension into hard palate and/or middle meatus, except extension to posterior wall of the maxillary sinus and pterygoid plates |

T3 | Tumor invades any of the following: bone of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, subcutaneous tissues, floor or medial wall of the orbit, pterygoid fossa, or the ethmoid sinuses |

T4a | Moderately advanced local disease |

| Tumor invades the anterior orbital contents, skin of the cheek, pterygoid plates, infratemporal fossa, cribriform plate, sphenoid or frontal sinuses |

T4b | Very advanced local disease |

| Tumor invades any of the following: dura, brain middle cranial fossa, cranial nerves (other than V2), nasopharynx, or clivus |

Table 23.2 Sinonasal Carcinoma—TNM System: Nasal Cavity and Ethmoid Sinus Invasion

Stage | Description |

T1 | Tumor restricted to any one sub-site, with or without bony invasion |

T2 | Tumor invading two sub-sites in a single region or extending to involve an adjacent region within the nasoethmoidal complex, with or without bony invasion |

T3 | Tumor extends to invade the medial wall or floor of the orbit, maxillary sinus, palate, or cribriform plate |

T4a | Moderately advanced local disease |

| Tumor invades any of the following: anterior orbital contents, skin of the nose or cheek, minimal extension to the anterior cranial fossa, pterygoid plates, sphenoid or frontal sinuses |

T4b | Very advanced local disease |

| Tumor invades any of the following: orbital apex, dura, brain, middle cranial fossa, cranial nerves (other than V2), nasopharynx, or clivus |

General Surgical Treatment Principles of Sinonasal Malignancies7,8

Because sinonasal malignancies often present at an advanced stage with skull base or orbital involvement, the gold standard for surgical excision has been the open craniofacial approach with bifrontal craniotomy and transfacial approach.

• With the advent and growth of endoscopic sinus surgery, early stage tumors (no skull base or orbital involvement) may be feasibly resected with a completely endonasal approach.

The tumor can initially be debulked in the sinonasal cavity, where it is not attached to the surrounding mucosa (i.e., filling an air-filled cavity).

The tumor can initially be debulked in the sinonasal cavity, where it is not attached to the surrounding mucosa (i.e., filling an air-filled cavity).

Table 23.3 Regional Lymph Nodes: TNM System

Stage | Description |

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, ≤ 3 cm in greatest dimension |

N2a | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, > 3 cm but ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N2b | Metastases in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N2c | Metastases in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension |

N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node, > 6 cm in greatest dimension |

Areas of bony attachment should either be resected where feasible or drilled down with a high-speed diamond drill bit.

Areas of bony attachment should either be resected where feasible or drilled down with a high-speed diamond drill bit.

• As experience has been gained with extended endoscopic approaches, selected advanced stage tumors have been treated successfully with endoscopic craniofacial resection (see page 464).

The intranasal portion of the tumor is first debulked to provide visualization (again, no tissue planes are violated).

The intranasal portion of the tumor is first debulked to provide visualization (again, no tissue planes are violated).

The endoscopic transcribriform approach is often the standard corridor used to gain access to the anterior skull base (see page 424).

The endoscopic transcribriform approach is often the standard corridor used to gain access to the anterior skull base (see page 424).

The tumor attachment along the superior septum or skull base is left so that the entire skull base and cribriform plate can be mobilized in an en-bloc fashion.

The tumor attachment along the superior septum or skull base is left so that the entire skull base and cribriform plate can be mobilized in an en-bloc fashion.

The bony medial orbital wall is often resected on the ipsilateral side of the tumor.

The bony medial orbital wall is often resected on the ipsilateral side of the tumor.

Control of the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries is necessary to devascularize the tumor and minimize bleeding and orbital complications.

Control of the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries is necessary to devascularize the tumor and minimize bleeding and orbital complications.

Once the skull base has been opened, the intracranial components of the tumor resection process proceed following oncological principles.

Once the skull base has been opened, the intracranial components of the tumor resection process proceed following oncological principles.

• Contraindications to the endoscopic craniofacial resection include brain parenchyma, intraorbital, cavernous sinus, or carotid artery involvement where complete resection is not surgically feasible.

Malignant Sinonasal Tumors of Epithelial Origin

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common sinonasal malignancy, with a peak incidence in the sixth to seventh decade of life.

• Maxillary sinus involvement is most common.

• Pathology (see also on page 156)

Divided into keratinizing, nonkeratinizing or undifferentiated subtypes.

Divided into keratinizing, nonkeratinizing or undifferentiated subtypes.

1 to 7% are seen in association with sinonasal inverted papilloma.

1 to 7% are seen in association with sinonasal inverted papilloma.

• Treatment

Early-stage tumors T1 and T2 are effectively treated with single-modality treatment (surgery or radiotherapy).

Early-stage tumors T1 and T2 are effectively treated with single-modality treatment (surgery or radiotherapy).

Advanced tumors (T3 and T4) require a combined approach (surgery plus adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy).

Advanced tumors (T3 and T4) require a combined approach (surgery plus adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy).

• The 5-year survival ranges from 40 to 70%.

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma3,9

• Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is the second most common sinonasal malignancy of epithelial origin and accounts for 10% of all non-SCC in the head and neck region.

• It commonly occurs in the maxillary sinus and nasal cavity.10

• There are three histological subtypes: cribriform, tubular, and solid (see on page 158).

• It is typically a slow-growing neoplasm, but recurrences can develop 10 to 20 years after the initial treatment.

• It has a propensity for perineural invasion with intracranial extension.

The most frequently involved cranial nerves are the maxillary and vidian nerves.

The most frequently involved cranial nerves are the maxillary and vidian nerves.

This one characteristic of ACC makes achieving negative surgical margins difficult and accounts for its poor long-term prognosis.

This one characteristic of ACC makes achieving negative surgical margins difficult and accounts for its poor long-term prognosis.

• Regional lymph node involvement ranges from 10 to 30%.11 Distant hematogenous spread is more common, with an incidence of 40% (most likely to lung and bone).12

• Treatment

Surgical resection of tumors with negative surgical margins remains the gold standard of treatment.

Surgical resection of tumors with negative surgical margins remains the gold standard of treatment.

Open or endoscopic approaches are used depending on the resectability of the tumor (the difficulty lies in achieving negative margins with perineural invasion).

Open or endoscopic approaches are used depending on the resectability of the tumor (the difficulty lies in achieving negative margins with perineural invasion).

Adjuvant postoperative radiation is often used to enhance local control.13

Adjuvant postoperative radiation is often used to enhance local control.13

Systemic chemotherapy is not yet fully defined but can be considered for patients with recurrent, metastatic, or unresectable disease.14

Systemic chemotherapy is not yet fully defined but can be considered for patients with recurrent, metastatic, or unresectable disease.14

The 5-year survival is 60 to 70%.15

The 5-year survival is 60 to 70%.15

The 10-year survival is 31%.

The 10-year survival is 31%.

Adenocarcinoma2,4,16,17

• Adenocarcinoma is a malignancy arising from glandular cells in the sino-nasal cavity, and it is the third most common sinonasal malignancy.

• There are two types: intestinal and nonintestinal (see also on page 157).

• Treatment involves complete surgical excision (open craniofacial or endoscopic) with possible adjuvant radiation (depending on margins and stage).

• Intestinal adenocarcinoma:

Similar to adenocarcinoma of the intestinal tract

Similar to adenocarcinoma of the intestinal tract

Occupational risk factors: wood and leather dust exposure

Occupational risk factors: wood and leather dust exposure

Site of involvement: ethmoid sinus (40%), nasal cavity (20%), maxillary sinus (20%)

Site of involvement: ethmoid sinus (40%), nasal cavity (20%), maxillary sinus (20%)

5-year survival: 40 to 60%

5-year survival: 40 to 60%

• Nonintestinal adenocarcinoma:

Divided into low and high grade.

Divided into low and high grade.

Low grade has a slower clinical presentation with a unilateral nasal mass.

Low grade has a slower clinical presentation with a unilateral nasal mass.

High-grade tumors present with locally advanced symptoms of orbital, infratemporal fossa, or intracranial extension.

High-grade tumors present with locally advanced symptoms of orbital, infratemporal fossa, or intracranial extension.

Low-grade tumors: 5-year survival is 85%.

Low-grade tumors: 5-year survival is 85%.

High-grade tumors: 3-year survival is 20%.

High-grade tumors: 3-year survival is 20%.

Malignant Tumors of Nonepithelial Origin

Esthesioneuroblastoma (ENB)

Esthesioneuroblastoma is a rare malignant tumor of the nasal vault probably derived from the olfactory epithelium covering the superior third of the nasal septum, cribriform plate, and superior nasal conchae, although this is controversial.18–21 It is also referred to as an olfactory placode tumor, esthesioneurocytoma, esthesioneuroepithelioma, esthesioneuroma, olfactory neuroblastoma, and olfactory neurogenic tumor.19,21

• Epidemiology and pathology (see also on page 161):

The histological findings suggest a classification system of four grades (Hyams’s histopathological grades),22 based on the cytoarchitecture of the tumor, the mitotic rate, the nuclear pleomorphism, the presence of rosettes, and necrosis. This classification is relevant to the prognosis, with grade I tumors having an excellent prognosis and grade IV being almost uniformly fatal.

The histological findings suggest a classification system of four grades (Hyams’s histopathological grades),22 based on the cytoarchitecture of the tumor, the mitotic rate, the nuclear pleomorphism, the presence of rosettes, and necrosis. This classification is relevant to the prognosis, with grade I tumors having an excellent prognosis and grade IV being almost uniformly fatal.

The differential diagnoses includes sinonasal carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphoma, mucosal malignant melanoma, paraganglioma, meningioma, invasive pituitary adenoma, sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma.

The differential diagnoses includes sinonasal carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphoma, mucosal malignant melanoma, paraganglioma, meningioma, invasive pituitary adenoma, sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma.

• Esthesioneuroblastoma entails slow progression with aggressive clinical behavior, often involving and destroying the surrounding structures: ethmoid bone and cribriform plate, olfactory nerves, frontal sinus, sphenoid sinus, nasopharynx, anterior cranial fossa, orbits, nasal cavity, and antrum.

Surgical Anatomy Pearl

About 50 to 75% of esthesioneuroblastomas involve the anterior skull base.

• Signs and symptoms: The most typical presentation of esthesioneuroblastoma is unilateral nasal obstruction and epistaxis with or without olfactory impairment. Other possible findings19,23–27 are headache, rhinitis/rhinorrhea, sinusitis, proptosis, diplopia, visual impairment, exophthalmia, facial pain, and excessive lacrimation. Nasal/facial masses may be visible or palpable. The involvement of the frontal lobes may give rise to frontal lobe symptoms or seizures.

Table 23.4 Esthesioneuroblastoma: TNM Staging System30

Stage | Description |

|

T1 | Nasal cavity or paranasal sinus involvement (excluding the sphenoid sinus) | |

T2 | Like T1, but the sphenoid sinus is included, with extension/erosion of the cribriform plate | |

T3 | Orbit/anterior skull base extension, without dural invasion | |

T4 | Brain invasion | |

Cervical lymph-node metastasis No: N0; Yes: N1 | Metastases No: M0; Yes: M1 | |

• Classification systems

These tumors are classified according to tumor extension (Kadish and modified Kadish classifications).28,29

These tumors are classified according to tumor extension (Kadish and modified Kadish classifications).28,29

Stage A: tumor limited to the nasal cavity

Stage A: tumor limited to the nasal cavity

Stage B: nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

Stage B: nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

Stage C: tumor extension beyond the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

Stage C: tumor extension beyond the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

Stage D: cervical or distant metastases29

Stage D: cervical or distant metastases29

TNM staging system30 (Table 23.4)

TNM staging system30 (Table 23.4)

Hyams’s histopathological grades are generally analyzed in two groups: grades I and II are typically grouped together, as are grades III and IV.31

Hyams’s histopathological grades are generally analyzed in two groups: grades I and II are typically grouped together, as are grades III and IV.31

• Treatment: Surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy is currently considered the gold standard for achieving the best prognosis, although there is controversy regarding the role of neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy.31–34 Single-modality therapy (e.g., only surgery or only radiotherapy) may be considered in low-volume T1 disease.31

Chemotherapy can be considered in patients with advanced disease.34–37

Chemotherapy can be considered in patients with advanced disease.34–37

Radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy.

• Surgical approaches: The aim in surgical resection is to perform an en-bloc resection of the tumor. Because many tumors present at an advanced stage with intracranial involvement (Kadish stage C), the gold standard approach is the craniofacial resection (CFR). This can be performed via an external/transfacial or endonasal/endoscopic-assisted approach (see Chapters 15 and 16). The surgery involves removing the tumor along with the entire ipsilateral cribriform plate, crista galli, olfactory bulb, and dura.

• Surgical complications: There is an overall complication rate of 30 to 40%. Central nervous system (CNS) complications (cerebral haemorrhage, cerebral edema, meningitis, stroke, frontal syndrome, frontal abscess, cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] leak) occur at a rate of 19.2%, orbital complications occur at a rate of 1.3%, and wound infections occur at a rate of 14.6%.33,35

Table 23.5 Ten-Year Overall Survival and Disease-Specific Survival: Kadish Classification

Kadish Stage | 10-Year Overall Survival (%) | 10-Year Disease-Specific Survival (%) |

A | 83.4 | 90 |

B | 49 | 68.3 |

C | 38.6 | 66.7 |

D | 13.3 | 35.6 |

• Outcome: The overall 5-year survival rate is 62 to 83.4%, and the 10-year survival rate is 45 to 76.1%.29–31,33–35,38–40 The local recurrence rate is 15 to 40%.29,34,35,40,41 The regional recurrence rate is 15 to 20%.29,30,35,42,43 An advanced Kadish stage (with intracranial and intraorbital involvement) has been found to be predictive of worse outcomes39 (Table 23.5).

A recent institutional review has suggested that Hyams’s histological grading is also a significant predictor of outcome independent of Kadish stage (high-grade ENBs have worse overall survival and disease-free survival compared with low-grade ENBs).34

A recent institutional review has suggested that Hyams’s histological grading is also a significant predictor of outcome independent of Kadish stage (high-grade ENBs have worse overall survival and disease-free survival compared with low-grade ENBs).34

Mucosal Melanoma4,44,45

• Mucosal melanoma is a rare tumor arising from melanocytes either in the surface epithelium or the stroma (see also page 162).

• It most commonly arises de novo and not from a preexisting nevus or from skin metastases.

• It accounts for 0.1% of all sinonasal malignancies, with no gender-related differences.

• It is more commonly found in the nasal cavity, followed by the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses.

• Several histological subtypes have been described.

Various immunohistochemical stains are required to establish diagnosis and distinguish mucosal melanoma from other small blue-cell tumors.

Various immunohistochemical stains are required to establish diagnosis and distinguish mucosal melanoma from other small blue-cell tumors.

• Mucosal melanoma is associated with a much poorer prognosis than other sinonasal malignancies involving the skull base, and it has a high risk of local recurrence.46

• Treatment: Traditionally, complete surgical excision of the tumor (either open craniofacial or endoscopic approaches) with negative margins was regarded as the gold standard of treatment.

Adjuvant postoperative radiotherapy has been used to enhance local disease control.4

Adjuvant postoperative radiotherapy has been used to enhance local disease control.4

A multicenter study demonstrated that the use of postoperative radiation is a key predictor of overall, disease-free, and recurrence-free survival (independent of negative surgical margins).46

A multicenter study demonstrated that the use of postoperative radiation is a key predictor of overall, disease-free, and recurrence-free survival (independent of negative surgical margins).46

Given the potential morbidity associated with either open or endoscopic craniofacial resections, the goals of surgery must be strongly considered and discussed in a multidisciplinary approach when the tumor invades the skull base or orbit.47

Given the potential morbidity associated with either open or endoscopic craniofacial resections, the goals of surgery must be strongly considered and discussed in a multidisciplinary approach when the tumor invades the skull base or orbit.47

The role of systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy is still not completely defined.

The role of systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy is still not completely defined.

The 3-year overall, disease-free, and recurrence-free survival rates are 28.2%, 29.7%, 25.5%, respectively.46

The 3-year overall, disease-free, and recurrence-free survival rates are 28.2%, 29.7%, 25.5%, respectively.46

Sinonasal Undifferentiated Carcinoma (SNUC)2,45,48

This is a rare, highly aggressive neuroendocrine tumor that typically presents with advanced disease.

• It has a broad age range, between the third and ninth decade of life, with a male predominance of 2–3:1.

• Clinically, symptoms progress rapidly (weeks to months) with local invasion of bone and surrounding structures.

• Histologically, differentiation between SNUC and olfactory neuroblastoma is important, given their vastly different clinical behavior and prognosis (see also page 159).

• Treatment consists of a multimodal approach that includes a combination of surgery (open craniofacial resection or endoscopic in carefully selected individuals) with adjuvant radiation and/or chemotherapy.

• Prognosis is poor, with a recent literature review demonstrating a 5-year survival of 6.25%, with a median overall survival of 12.7 months.48

Clival Chordoma

• See chordoma on page 165 (Pathology) and Chapter 22.4, page 585 (Treatment).

Region II49,50

Region II49,50

Tumors of the infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossa not frequently originate primarily from these regions. Instead, these spaces are most often involved secondarily due to neoplastic processes from neighboring structures such as the paranasal sinuses and the nasopharynx. Moreover, because of the privileged anatomy of the infratemporal fossa and its close proximity to the middle cranial fossa and its various skull base foramina (review anatomy on page 35), malignant tumors that involve this region have multiple potential routes of spread to the cranial base.

Signs and Symptoms

• Clinically, primary tumors that occupy this region may not initially produce any significant symptoms because its location lateral to the nasal cavity and posterior to maxillary sinus.

• Advanced or neurogenic tumors may present with symptoms of pain or paresthesia along the maxillary or mandibular nerve distribution.

• Involvement of the pterygoid muscles may produce trismus.

• Extension through the inferior orbital fissure may produce orbital symptoms (e.g., diplopia, proptosis).

Tumors of the Infratemporal Fossa

Types

• Primary

Accounts for 25 to 30% of all tumors

Accounts for 25 to 30% of all tumors

Includes hemangioma, lipoma, hemangiopericytoma, meningioma, neurofibroma, osteosarcoma, schwannoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, lymphoma

Includes hemangioma, lipoma, hemangiopericytoma, meningioma, neurofibroma, osteosarcoma, schwannoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, lymphoma

• Secondary

Accounts for 70 to 75% of all tumors

Accounts for 70 to 75% of all tumors

Includes sinonasal carcinoma (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma), juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, glomus tumor

Includes sinonasal carcinoma (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma), juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, glomus tumor

General Treatment Principles

• Most benign primary tumors of region II can be managed with a single modality if treatment is warranted (usually surgery).

• Malignant tumors of this region usually require multimodality therapy with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy.

Surgical Approaches to the Infratemporal Fossa

• Traditionally, approaches to the infratemporal fossa have been performed via external approaches including the following:

Transfacial techniques: see Chapter 15.

Transfacial techniques: see Chapter 15.

Subtemporal/infratemporal approach with orbitozygomatic osteotomy: see frontotemporal-orbitozygomatic (FTOZ) approach (page 353).

Subtemporal/infratemporal approach with orbitozygomatic osteotomy: see frontotemporal-orbitozygomatic (FTOZ) approach (page 353).

More recently, expanded endoscopic techniques have been used to treat a variety of tumor pathologies in the pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossa.51 This most often involves an extended trans-pterygoid approach: see Chapter 16, page 428.

More recently, expanded endoscopic techniques have been used to treat a variety of tumor pathologies in the pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossa.51 This most often involves an extended trans-pterygoid approach: see Chapter 16, page 428.

Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

• Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA) is a rare benign vascular tumor of the nasopharynx heavily skewed toward affecting males primarily during adolescence.

• It is believed that JNA accounts for 0.05 to 0.5% of head and neck tumors.

• The incidence is estimated to be 3.7 cases per million males in the age range of 10 to 24 years.52

• The median age is 15 years.

Etiology/Pathogenesis

• Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is classically located in the nasopharynx, nasal cavity, sphenoid sinus, or pterygopalatine fossa.53

• The blood supply of JNA originates from the sphenopalatine artery and other end branches of the external carotid artery.

• In advanced disease, JNA can receive blood supply from the internal carotid artery system.

• Several staging systems (Andrews, Chandler, and Radkowski classifications) have been proposed based on extension of the tumor and the amount of intracranial extension.54

• Although JNA is a benign tumor, life-threatening complications can arise secondary to hemorrhage or intracranial extension.

• Its growth pattern is aggressive and can induce bone remodeling as it expands.

• Intracranial involvement has been reported to occur in 10 to 36% of cases, with the anterior and middle cranial fossa being the most common sites of invasion.55

• Four potential routes to the cranial cavity:

From the infratemporal fossa through the floor of the middle cranial fossa (most common)

From the infratemporal fossa through the floor of the middle cranial fossa (most common)

From the pterygomaxillary fissure and infratemporal fossa into the superior and inferior orbital fissures

From the pterygomaxillary fissure and infratemporal fossa into the superior and inferior orbital fissures

Through direct erosion of the sphenoid sinus into the region of the sella turcica and cavernous sinus

Through direct erosion of the sphenoid sinus into the region of the sella turcica and cavernous sinus

Along the ethmoid skull base and cribriform plate into the anterior cranial fossa

Along the ethmoid skull base and cribriform plate into the anterior cranial fossa

Pathology

See page 155.

Clinical Presentation

• Presenting symptoms include nasal obstruction, epistaxis, nasal discharge, pain, sinusitis, facial deformation, diplopia, hearing impairment, and otitis media52

Diagnosis

• Biopsy is not routinely performed due to the potential for severe epistaxis.

• On computed tomography (CT), the classic finding is the Holman-Miller sign with expansion of the pterygopalatine fossa and bulging of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus.

• Computed tomography angiography (CTA) or angiography identifies the primary vessels that feed the tumor and enables preoperative embolization before surgical resection to minimize blood loss.53

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates the presence of soft tissue/intracranial extension.

Treatment

• Preoperative angiography + embolization of the feeding vessels of the external carotid artery system

• Surgery

Endoscopic transnasal approaches have been used successfully to treat JNA without intracranial extension.

Endoscopic transnasal approaches have been used successfully to treat JNA without intracranial extension.

Initially requires debulking of the intranasal portion of the tumor and isolating the main feeding vessel (often the sphenopalatine and maxillary artery)54

Initially requires debulking of the intranasal portion of the tumor and isolating the main feeding vessel (often the sphenopalatine and maxillary artery)54

Commonly involves transpterygoid, and transsphenoidal approaches to fully resect the tumor; see Chapter 16

Commonly involves transpterygoid, and transsphenoidal approaches to fully resect the tumor; see Chapter 16

External transfacial approaches

External transfacial approaches

Often reserved for JNA with intracranial involvement

Often reserved for JNA with intracranial involvement

Approaches include transpalatal, lateral rhinotomy, midfacial degloving, facial translocation; see external transfacial approaches (Chapter 15)

Approaches include transpalatal, lateral rhinotomy, midfacial degloving, facial translocation; see external transfacial approaches (Chapter 15)

A recent systematic review did not find a statistically significant difference in the recurrence rates of JNA treated with endoscopic approaches and those treated with external approaches.53

A recent systematic review did not find a statistically significant difference in the recurrence rates of JNA treated with endoscopic approaches and those treated with external approaches.53

One study suggests that open approaches should be reserved for tumors with significant intracranial involvement (e.g., internal carotid artery, cavernous sinus, optic nerve).4

One study suggests that open approaches should be reserved for tumors with significant intracranial involvement (e.g., internal carotid artery, cavernous sinus, optic nerve).4

• Radiotherapy

Can be used for unresectable tumors with intracranial extension or recurrences.

Can be used for unresectable tumors with intracranial extension or recurrences.

Tumor control has been found following a single course of 30 to 35 Gy.

Tumor control has been found following a single course of 30 to 35 Gy.

Despite these results, it is still considered controversial to treat a benign neoplasm with potentially harmful radiotherapy.55

Despite these results, it is still considered controversial to treat a benign neoplasm with potentially harmful radiotherapy.55

Outcome

• Recurrence rates range from 6 to 50%.52,53

Sinonasal Carcinoma

See discussion in Region I, above.

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

• Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a nonlymphomatous SCC arising from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx.56

Epidemiology

• It is an uncommon disease in most countries (age-adjusted incidence < 1/100,000), but it occurs at a much higher frequency in southern China, northern Africa, and Alaska, especially among the Inuits of Alaska and the ethnic Chinese living in Guangdong.

• Reported incidence in Hong Kong (geographically adjacent to Guangdong province) is 20 to 30 per 100,000 men and 15 to 20 per 100,000 women. It is classified as World Health Organization (WHO) types II and III.

• In North America and Western Europe, NPC occurs sporadically and is primarily related to exposure to alcohol and tobacco. It is classified as WHO type I.57

In North American populations and Mediterranean regions, the age distribution of NPC is bimodal, with peaks at 10 to 20 years and 40 to 60 years.

In North American populations and Mediterranean regions, the age distribution of NPC is bimodal, with peaks at 10 to 20 years and 40 to 60 years.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

• Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is consistently detected in patients with NPC.56 EBV-encoded RNA signal as detected by in-situ hybridization is present in nearly all tumor cells, and EBV can be detected from premalignant lesions, suggesting its role in the pathogenesis of the disease.

• There is a strong association with EBV infections as well as genetic factors such as human leukocyte antigen (HLA), suggesting that the interplay between environment and genetics is at the root of its pathogenesis.57

• Histologically classified by WHO into three groups: type I, keratinizing SCC; type II, nonkeratinizing SCC; type III, undifferentiated carcinoma (the most common form).56

• Children with NPC almost always have type III, which is more associated with locoregional spread and distant metastases.58

Pathology

See page 159.

Clinical Presentation56,59

• Nonspecific symptoms such as epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and nasal discharge may develop as the tumor enlarges in the posterior nasal space.

• Otologic symptoms such as unilateral serous otitis media/conductive hearing loss may be the initial presenting symptom as the tumor obstructs the eustachian tube.

• Cranial neuropathies (cranial nerves [CNs] V and VI) may develop as the tumor extends superiorly to involve the skull base, with symptoms of facial numbness and diplopia.

• Posterior triangle neck masses may indicate cervical metastases; this can be the initial presenting symptom.

Diagnosis

• If there is any suspicion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, a thorough nasal-endoscopic exam is mandatory.

Particularly important in adult Asian patients who are presenting with a unilateral serous otitis media

Particularly important in adult Asian patients who are presenting with a unilateral serous otitis media

• A definitive diagnosis is obtained with a biopsy.

• CT and MRI are again complementary modalities in determining the extent of the tumor.

Staging of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

See Table 23.6.

Treatment56

• External beam radiotherapy

Standard treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Standard treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Definitive radiotherapy alone in T1 tumors.

Definitive radiotherapy alone in T1 tumors.

Table 23.6 Staging of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Stage | Description |

T stage |

|

T1 | Tumor confined to nasopharynx, or tumor extends to oropharynx and/or nasal cavity without parapharyngeal extension |

T2 | Tumor with parapharyngeal extension |

T3 | Tumor involves bony structures of the skull base and/or paranasal sinuses |

T4 | Tumor with intracranial extension and/or involvement of cranial nerves, hypopharynx, orbit or with extension to the infratemporal/masticator space |

N stage |

|

N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

N1 | Unilateral metastases in cervical lymph node ≤ 6 cm, above supraclavicular fossa, and/or unilateral or bilateral, retropharyngeal lymph nodes ≤ 6 cm |

N2 | Bilateral metastasis in cervical lymph nodes ≤ 6 cm, above supraclavicular fossa |

N3 | Metastases in a lymph node > 6 cm and/or to supraclavicular fossa |

N3a | > 6 cm in dimension |

N3b | Extension to the supraclavicular fossa |

Used in combination with chemotherapy for T2–T4 tumors.

Used in combination with chemotherapy for T2–T4 tumors.

Prophylactic neck irradiation is undertaken given the high incidence of occult neck disease.

Prophylactic neck irradiation is undertaken given the high incidence of occult neck disease.

• Chemotherapy

Studies have shown that concurrent chemotherapy alongside radiotherapy can improve both relapse-free survival and overall survival.11 This approach is employed by most major centers for T2–T4 disease.

Studies have shown that concurrent chemotherapy alongside radiotherapy can improve both relapse-free survival and overall survival.11 This approach is employed by most major centers for T2–T4 disease.

• Salvage therapy for residual/recurrent disease

Re-irradiation

Re-irradiation

Surgical resection

Surgical resection

Primary NPC is generally not treated with surgery, given the complexity of the anatomy and the fact that the tumor is highly radiosensitive.

Primary NPC is generally not treated with surgery, given the complexity of the anatomy and the fact that the tumor is highly radiosensitive.

For residual/recurrent disease, nasopharyngectomy may be considered.

For residual/recurrent disease, nasopharyngectomy may be considered.

Infratemporal lateral approaches: see page 377.

Infratemporal lateral approaches: see page 377.

Transfacial approaches: see Chapter 15.

Transfacial approaches: see Chapter 15.

More recently, endoscopic nasopharyngectomy has been described, which applies many of the extended endoscopic principles (transpterygoid, transclival)60; see Chapter 16.

More recently, endoscopic nasopharyngectomy has been described, which applies many of the extended endoscopic principles (transpterygoid, transclival)60; see Chapter 16.

Outcome6

• Overall 5-year survival rates:

Stage I: 70–80%

Stage I: 70–80%

Stage II: 64%

Stage II: 64%

Stage III: 62%

Stage III: 62%

Stage IV: 38%

Stage IV: 38%

Region III

Region III

These are the rarest extracranial skull base neoplasms. Tumors can arise from the external auditory canal (EAC), middle ear, mastoid, or parotid gland. Because of their vastly different biology and treatment principles, we divide them into temporal bone and parotid neoplasms.

Temporal Bone Neoplasms

• Can involve primary neoplasms of the EAC, middle ear, mastoid, or secondary metastases to the temporal bone.

Note that primary neoplasms arising from the auricle (pinna) are considered separate from primary temporal bone neoplasms.

Note that primary neoplasms arising from the auricle (pinna) are considered separate from primary temporal bone neoplasms.

• Malignancies are extremely rare, with a reported incidence of 1 to 6 per million.61,62

• Accounts for 0.2% of head and neck tumors.

• Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common malignancy in adults, followed by basal cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma.63

• In pediatric patients, the most common diagnosis is rhabdomyosarcoma.64

• Given the rarity of temporal bone neoplasms reported in the literature, various histological subtypes are often grouped together when discussing management and treatment.

• As it relates to the skull base, temporal bone malignancies are the most relevant, and a general overview of the various histological subtypes and treatment paradigms will be discussed in this chapter.

• Differential diagnosis of temporal bone neoplasms: Tables 23.7 and 23.8.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma65

• Pathology: see page 160.

• Accounts for the majority of temporal bone malignancies.

• Most commonly arises from the skin of the external ear

Table 23.7 Benign Temporal Bone Neoplasms

Tissue | Neoplasm |

Epithelial | Pleomorphic adenoma Ceruminous adenoma Papilloma Papillary adenoma |

Mesenchymal | Lipoma Myxoma Hemangioma Schwannoma Neurofibroma Osteoma Chondroblastoma |

Neuroendocrine | Paraganglioma |

Other | Meningioma Teratoma |

Table 23.8 Malignant Temporal Bone Neoplasms

Tissue | Neoplasm |

Epithelial | Squamous cell carcinoma Basal cell carcinoma Ceruminal gland adenocarcinoma Adenoid cystic carcinoma Endolymphatic sac tumor |

Mesenchymal | Rhabdomyosarcoma Osteosarcoma Chondrosarcoma Malignant schwannoma |

Hematologic | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Plasmacytoma |

Neuroendocrine | Neuroendocrine carcinoma Carcinoid |

Other | Melanoma Langer’s cell histiocytosis Metastases |

Not associated with alcohol and tobacco use (unlike other head and neck SCCs)

Not associated with alcohol and tobacco use (unlike other head and neck SCCs)

Associated with chronic inflammation or infection of the EAC

Associated with chronic inflammation or infection of the EAC

• Early lesions present as either a flat or raised lesion of the EAC or pinna.

• As the tumor grows, it can directly invade soft tissue and temporal bone or spread through perineural or lymphatic invasion.

Basal Cell Carcinoma66

• Pathology: Nonmelanocytic skin cancer arising from basal cells found in lower layer of epidermis.

• Commonly found in EAC and pinna.

• Presents as an ulcer with raised borders and telangiectasias.

• Actinic exposure is a risk factor.

• Previous studies have suggested a better prognosis than for SCC, although absolute numbers in any series are very small.

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma67

• Pathology: see page 158

• Most common EAC malignancy of glandular origin

• Can also arise in the middle ear (secondary to glandular rests) or from an invasion from the parotid gland

• Most common symptom is intractable pain

• Propensity for perineural and intracranial involvement; difficult to achieve negative margins

• High risk of local recurrences and distant metastases

5-year overall survival: 75%

5-year overall survival: 75%

10-year overall survival: 60%

10-year overall survival: 60%

Ceruminous Carcinoma68

• Rare tumor with a peak incidence in the fifth decade of life

• Similar presentation to other EAC malignancies

• Arises from the ceruminous glands of the EAC

• Invasion of surrounding structures distinguishes this from ceruminous adenoma

Adenocarcinoma69

• Pathology: see page 158

• Rare tumor arising from the middle ear

• More common in females

• Peak incidence: fourth decade

• Aggressive bony invasion often on CT

Rhabdomyosarcoma70

• Malignant mesenchymal tumor primarily occurring in children

• Locally invasive and destructive

• Temporal bone involvement accounts for 7% of all head and neck rhabdomyosarcomas

• Median age of presentation is 4.5 years

• Can present as otorrhea, EAC mass, or hearing loss; frequently misdiagnosed as middle ear disease (otitis media)

• Treatment involves a combination of chemotherapy and radiation

5-year disease-free survival: 81%

5-year disease-free survival: 81%

Endolymphatic Sac Tumors

• Rare slow-growing tumors arising from the endolymphatic sac or endolymphatic duct

• Typically locally aggressive, highly lytic into the temporal bone and mastoid process, with extension into the middle ear, posterior fossa, or cerebellopontine angle (CPA)

• Can cause massive destruction of the surrounding structures including the cochlea, vestibule, and internal auditory canal71

• Rare malignancy but associated with von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease in up to 16% of cases19,71–74

• Pathology: also known as adenocarcinoma of the endolymphatic sac

Papillary/glandular appearance with cuboidal epithelium that may resemble choroid plexus papilloma, especially given its vascular nature

Papillary/glandular appearance with cuboidal epithelium that may resemble choroid plexus papilloma, especially given its vascular nature

Glandular areas may show secretions resembling a colloid (thyroid-like)

Glandular areas may show secretions resembling a colloid (thyroid-like)

Immunohistochemistry: positive for cytokeratins and variable for glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP)

Immunohistochemistry: positive for cytokeratins and variable for glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP)

• Slow-growing and invasive but not known to metastasize

• Sporadic cases appear to be more aggressive than ones associated with VHL.75

von Hippel-Lindau syndrome: Rare autosomal dominant genetic disease, with an incidence of 1 in 39,000 births, characterized by central nervous system and retinal hemangioblastoma, clear cell renal carcinomas, pheochromocytomas, pancreatic cysts, neuroendocrine tumors, cystoadenomas of the reproductive adnexal organs, and endolymphatic sac tumors. Patients are generally affected by headaches, ataxia, dizziness, unilateral hearing loss, visual loss, loss of spinal function, hypertension, or renal cell carcinoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Once the tumor origin/attachment is identified with the endoscopic approach, it is then removed in an en-bloc fashion (typically in a submucoperiosteal plane) with adequate oncological mucosal margins.

Once the tumor origin/attachment is identified with the endoscopic approach, it is then removed in an en-bloc fashion (typically in a submucoperiosteal plane) with adequate oncological mucosal margins.