Familial Frontal Lobe Epilepsies

Fabienne Picard

Eylert Brodtkorb

Introduction

Frontal lobe epilepsies, as with other focal epilepsies, were formerly invariably considered to be the consequence of an overt or obscure brain lesion. However, this view has changed during the last 10 years, as large families comprising several individuals with non–age-related partial seizures without manifest organic cause have been identified. Today, the genetic origin of nonlesional focal epilepsies is well accepted. Several familial focal epilepsy syndromes with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance have successively been recognized, such as autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (ADNFLE), familial temporal lobe epilepsies, and familial focal epilepsy with variable foci.46 They are considered idiopathic, like the classical benign localization-related epilepsies of childhood, since affected individuals do not exhibit any other etiology than a presumed genetic cause.

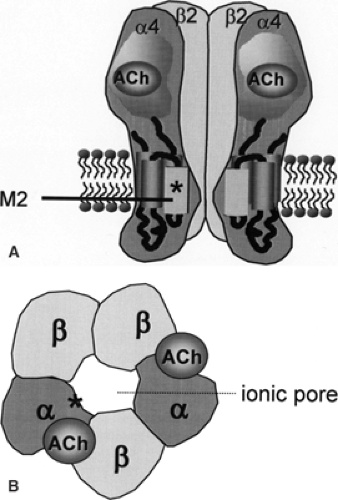

ADNFLE constitutes a reasonably homogeneous clinical syndrome. Mutations have been identified in genes coding for subunits of the cerebral nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) in some families, establishing a clear link between ADNFLE and this ion channel. The many cases of sporadic nonlesional nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (NFLE) present similar clinical and electroencephalographic features.66 It is likely that some of them represent unrecognized familial cases or are related to de novo mutations. Yet, others possibly share similar pathophysiologic mechanisms, even if their etiology is not predominantly genetic.

Historical Perspectives

In the last 30 years, several reports have described patients with sudden, brief nocturnal episodes of complex motor activity and a family history of similar attacks.18,27,68 This clinical picture was originally thought to represent a movement disorder, so-called paroxysmal nocturnal dystonia,32,33 but was later recognized as epilepsy.23,37 In 1993, Vigevano and Fusco used the term partial idiopathic epilepsy of frontal lobe origin to describe otherwise healthy children presenting with nocturnal tonic postural seizures with a strong family history of epilepsy.72 When families with a clear mendelian inheritance later were identified by Scheffer et al. in 1994, this disorder was designated ADNFLE.59 The first reported families originated in Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. In the Australian family, linkage studies revealed mapping to the long arm of chromosome 20.44 Subsequent sequencing demonstrated a missense mutation in the gene coding for a subunit of the neuronal nAChR.63 This finding was a surprise, as it was not previously known that this receptor was involved in epileptogenesis. ADNFLE was the first epileptic syndrome with a proven monogenetic origin, a finding that may be considered a milestone in epileptology. Various mutations in genes coding for subunits of nAChRs have later been demonstrated in different families with this condition (Table 1).4,8,14,21,24,30,34,35,36,39,42,43,44,55,56,58,59,62,63,64

Definitions

ADNFLE was first described on the basis of its familial character, but does not differ clinically from the more frequently occurring sporadic cases of nonlesional NFLE. An attempt to define the general characteristics of frontal lobe epilepsy was part of the 1989 Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE)11:

“Frontal lobe epilepsies are characterized by simple partial, complex partial, secondarily generalized seizures or combinations of these. Seizures often occur several times a day and frequently occur during sleep. Frontal lobe partial seizures are sometimes mistaken for psychogenic seizures. Status epilepticus is a frequent complication.”

A list of features strongly suggestive of the diagnosis was given:

“(1) generally short seizures, (2) complex partial seizures arising from the frontal lobe, often with minimal or no postictal confusion, (3) rapid secondary generalization (more common in seizures of frontal than of temporal lobe epilepsy), (4) prominent motor manifestations which are tonic or postural, (5) complex gestural automatisms frequent at onset, (6) frequent falling when the discharges are bilateral.”

ADNFLE contains several elements from this general outline. However, the unique seizure semiology in this disorder was found to fit poorly with the 1981 ILAE seizure classification.12,31 Hence, the concept of hypermotor seizures was introduced in the more recent proposal of a semiologic seizure classification31:

“Hypermotor seizures are seizures in which the main manifestations consist of complex movements involving the proximal segments of the limbs and trunk. This results in large movements that appear ‘violent’ when they occur at high speeds. The ‘complex motor manifestations’ imitate normal movements, but the movements are inappropriate for the situation and usually serve no purpose. Frequently, the movements are stereotypically repeated in more or less complex sequences (e.g. pedalling). Consciousness may be preserved during these seizures.”

Finally, the term hyperkinetic seizure was included in the new glossary of descriptive terminology for ictal semiology by the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology6:

“(1) Involves predominantly proximal limb or axial muscles producing irregular sequential ballistic movements, such as pedalling, pelvic thrusting, thrashing, rocking movements. (2) Increase in rate of ongoing movements or inappropriately rapid performance of a movement”

ADNFLE follows an autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance. The first identified families allowed the

delineation of the main clinical features,58 which later have been refined (Table 2). Subsequently, other focal idiopathic epilepsies with an autosomal dominant transmission pattern were described: The familial temporal lobe epilepsies2 and the autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with variable foci.60 ADNFLE has together with these syndromes been included within the subgroup of “familial focal epilepsies” in the list of epilepsy syndromes recently proposed by the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology.15

delineation of the main clinical features,58 which later have been refined (Table 2). Subsequently, other focal idiopathic epilepsies with an autosomal dominant transmission pattern were described: The familial temporal lobe epilepsies2 and the autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with variable foci.60 ADNFLE has together with these syndromes been included within the subgroup of “familial focal epilepsies” in the list of epilepsy syndromes recently proposed by the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology.15

Table 1 Clinical Characteristics in Autosomal Dominant Nocturnal Frontal Lobe Epilepsy Families with Mutations in Genes Coding for Subunits of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 2 Main Clinical Features of Autosomal Dominant Nocturnal Frontal Lobe Epilepsy | |

|---|---|

|

Epidemiology

To date, the number of reported ADNFLE families exceeds 100.4,8,10,14,21,24,25,30,34,35,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,55,58,62 Undoubtedly, they only represent a small fraction of ADNFLE families worldwide and the prevalence of this disorder is obscure. Several known families have probably not been reported when genetic analyses have not been performed or have been inconclusive. In addition, it is likely that there still are families in which the epileptic nature of the paroxysmal nocturnal events has remained unrecognized or misdiagnosed. The reported ADNFLE families all comprise at least two affected first-degree relatives with an inheritance pattern suggestive of autosomal dominant transmission. Twenty-seven affected individuals have been reported in the largest and first described family in Australia.44 Up until now, mutations have been found in genes encoding subunits of nAChR in 12 families and in one sporadic case (Table 1). Thus, identified mutations currently account for only a minority (10% to 12%) of published ADNFLE families. Sporadic NFLE cases are relatively common,51 and some may harbor the same mutations that have been identified in ADNFLE.43

Etiology and Basic Mechanisms

ADNFLE was the first idiopathic epilepsy for which a responsible gene was recognized.

Mutations have been identified in the CHRNA4 gene encoding the nAChR α4 subunit and in the CHRNB2 gene encoding the nAChR β2 subunit (Table 1). Up until now, four different mutations have been described in CHRNA4: (a) S248F, a missense mutation replacing serine with phenylalanine in position 248 in the amino acid sequence, observed in an Australian, a Spanish, a Norwegian, and a Scottish family36,56,63,64; (b) 776ins3, an insertion of three nucleotides at nucleotide position 776, leading to the insertion of a leucine in the amino acid sequence, in another Norwegian family62; (c) S252L, a missense mutation replacing a serine by a leucine in position 252 in the amino acid sequence in a Japanese, a Polish, and a Korean family, and in a sporadic case of Lebanese origin who subsequently had an affected son8,21,24,35,43,55; and (d) T265I, another missense mutation, in a German family.30 Some authors use an alternative codon numbering, which may cause nomenclature confusion.10,55,56 Three different mutations (V287L, V287M, and I312M) are described in the CHRNB2 gene in an Italian, a Scottish, and an English family, respectively.4,14,42

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree