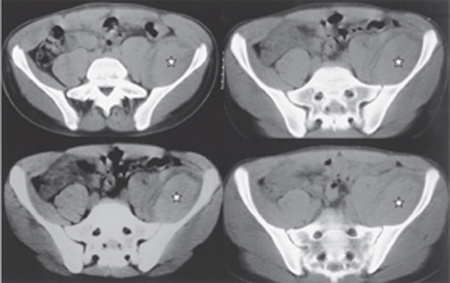

38 Femoral Neuropathy by Compression from Iliacus Compartment Hematoma A 15-year-old healthy male sustained a hip extension injury when falling backward on ice while skating. He developed intense pain in the left anterior groin region that continued for ˜5 days. The ultrasound of the groin region was reported as normal. The pain subsequently subsided to be replaced by progressive numbness and weakness in the femoral nerve distribution. There was no history of bleeding diathesis. Ten days after the initial injury, his neurological exam revealed slight weakness of the iliacus (grade 4/5, Medical Research Council), with no contraction of quadriceps (grade 0), normal adduction, and absent knee jerk. There was profoundly decreased sensation in the femoral (including saphenous) and lateral cutaneous nerve distributions. A Tinel sign could be elicited by tapping over the course of these nerves, just above the inguinal ligament. Computed tomographic (CT) scan revealed a 5 x 12 cm iliac fossa hematoma elevating the left iliacus muscle with an ill-defined lucent halo between the two (Fig. 38–1). Figure 38–1 Computed tomographic scan cuts at the upper pelvic level demonstrate a large soft tissue density mass in the left iliac fossa. The lesion (star) elevates the iliacus muscle away from the bone, pushing the psoas muscle medially. At surgery, a huge subacute hematoma was encountered and evacuated. Exposure of this area through a left retroperitoneal approach revealed stretching of the femoral and lateral cutaneous nerve between the muscle below and tense iliacus fascia above. After iliacus fasciotomy, the subiliacus hematoma was evacuated. The underlying iliacus muscle was found to be somewhat necrotic. A source of bleeding was not identified. Twelve months later, examination revealed normal psoas function with significant improvement in quadriceps power (grade 4/5). There was slight residual decreased sensation in the saphenous nerve distributions. Two years postoperatively, the patient had a normal neurological examination. Subacute femoral nerve compression neuropathy from iliacus hematoma The femoral nerve arises from the dorsal divisions of L2–4 ventral primary rami. It descends through the psoas major toward its inferolateral border, passes between the psoas and iliacus groove deep to the iliacus fascia, down to the thigh behind the inguinal ligament. Goodfellow et al, in their infusion experiments, concluded that the fascial compartment of the iliacus and psoas muscle are separate except for a communication in the thigh below the inguinal ligament. Later Nobel et al demonstrated as many as three distinct fascial layers reinforcing the distal portion of the iliacus fascia, which offer the rigidity to this region and provide the potential for compartment syndrome. The blood supply to the iliacus muscle is mainly from the iliac branches of the anterior division of the iliolumbar artery. The terminal branches of these arteries divide into a superficial division, which runs on the pelvic surface of the iliacus muscle, and a deep branch, which passes between the iliacus muscle and the periosteum to give rise to the nutrient artery of the iliac bone. These branches, mainly the deep ones, are avulsed and torn due to violent contraction and stretching of the iliacus muscle during traumatic injury. This is probably the source of posttraumatic iliacus hematoma. Initially after hemorrhage in the iliacus muscle fascia, the patient develops a severe pain in the groin and inguinal region with associated tender globular swelling in the iliac fossa. Occasionally, the hematoma extends into the psoas fascia inferiorly and causes additional fusiform swelling of the psoas compartment with a palpable groove between these two muscles. The swelling can also extend into the groin. Patients typically keep their hip flexed, abducted, and externally rotated to reduce tension on the iliopsoas muscle. Manifestations of femoral neuropathy will develop later, with its most severe form characterized by weakness and wasting of the quadriceps muscle, decreased or absent knee jerk, and sensory loss over the anteromedial aspect of the thigh and medial aspect of the lower leg. Variable hip flexion weakness due to iliacus muscle injury or its deterioration may also accompany the clinical picture. Most cases can be diagnosed on clinical grounds, supported by an appropriate imaging study. Electrodiagnostic investigation should be considered in clinically difficult cases to establish the femoral nerve functional status and to exclude other neural involvement. Radiographic investigation with CT scan of the iliopsoas compartment is not very specific; however, in the appropriate clinical context (e.g., trauma) it can confirm the location and size of the lesion, as would a well-performed ultrasound. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan will allow better soft tissue discrimination in cases inadequately imaged by CT. Imaging studies such as CT and MRI could also exclude other lesions such as herniated lumbar disks and spinal or retroperitoneal tumors that are part of the differential diagnosis. Management of this condition is controversial. Good results have been reported with both conservative and surgical treatment. Delay in the diagnosis and profound femoral neuropathy at the time of presentation and different etiologies of iliacus hematoma render any meaningful conclusion from the literature difficult to interpret in this uncommon entity. The case described here has presented with a large hematoma, which was operatively evacuated and has shown progressive recovery. Based on the proposed pathogenesis we feel that early fasciotomy with hematoma evacuation should be considered in any patient with acute iliacus hematoma and femoral neuropathy unless it is small. Even cases where the hematoma is small should be vigilantly observed for any symptoms or signs suggestive of compressive neuropathy, including severe progressive pain or early neurological symptoms, for at least a week after the insult. Serial CT scan can also be helpful in borderline cases. Patients with progressive hematoma size and advanced femoral neuropathy may have lost their optimal time for decompressive operation due to established ischemia (see discussion following here). The role of physiotherapy in the acute phase of a conservatively treated group remained questionable due to its potential aggravation of bleeding or swelling in the iliacus sheath. If this line of therapy is selected, vigilant neurological follow-up with associated serial imaging is warranted. Traumatic retroperitoneal hematoma in the iliacus muscle is an unusual but potentially serious cause of femoral compression neuropathy. Femoral compression neuropathy is a well-recognized entity associated with hemophilia, anti-coagulation therapy, cardiac catheterization, and major abdominopelvic operations. Occasionally, it is a consequence of traumatic iliacus hematoma due to sporting activities. The pathogenesis of femoral neuropathy has been related to iliac muscle hematoma. Continuous bleeding into the “iliacus compartment” will subject the femoral nerve to ischemia and compression neuropathy. Although several possible sites for hematoma have been described, this illustrative case clearly represents a submuscular hematoma possibly due to avulsion of the deep branch of the iliac muscle artery toward the ilium. Initial pain usually subsides and merges into a painless neuropathy. This is related to the progressive axonal compression and ischemia of the femoral nerve. Considering the anatomical substrates in the iliac fossa region for development of typical compartment syndrome and previous reports of intraoperative findings of iliacus muscle necrosis associated with neuropathy, we feel that the many patients with this clinical syndrome have developed muscle necrosis at the time of neuropathy. This necrosis will not be functionally significant and in the context of femoral neuropathy will go unnoticed. Although the frequent delay in neurological presentation after acute inguinal pain in some could be due to missed diagnosis in the early painful stage of the disease in a bedridden patient, it highly suggests a progressive increase in iliacus compartment pressure with ensuing neuropathy. Progressive bleeding can be a contributory factor. With increasing pressure in the osseofascial compartment progressive ischemia of the capillary wall in the muscle with subsequent swelling, interstitial edema, and reflex vasospasm in the muscle becomes more important in maintaining the vicious cycle of progressive ischemia and hypertension in the iliacus compartment. This could lead to muscle fiber necrosis. The femoral nerve is susceptible to compression, especially in the pelvis in the subfascial plane due to its supply by a single nutrient from the iliacus muscle artery. Lack of direct correlation between the hematoma size and development of the clinical syndrome may be explained by variable fascial compliance in different patients as well as rapidity with which hematomas develop. This latter factor points to the source of bleeding, which in cases of low-flow venous hemorrhage (e.g., coagulopathy) could be better tolerated.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Discussion

Discussion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree