Schematic diagram showing activities of daily living (ADLs) subclassified into basic (Basic ADLs) and instrumental (Instrumental ADLs).

The assessment of functional abilities should be included in clinical investigations of any individual with FTD, as they can aid in determining dementia severity and prognosis. The picture of ADL impairment in FTD tends to be quite complex because of the interplay of cognitive and behavioral deficits and their distinct impact on functional abilities. Importantly, assessment of ADLs should extend to include the primary progressive aphasias (PPAs), where most of the focus at diagnosis remains on assessment of language function, with little attention to assessment of functional performance [4, 5].

The assessment of functional decline can be conducted in a variety of ways. Informant-based report (questionnaire or interview) are commonly used in dementia settings. In research settings, performance-based assessments of ADL function offer a more controlled analysis of the performance. However, performance-based assessments can be rather constraining because they require specialist training and can be more time-consuming.

A point of debate in dementia, when assessing ADLs, is that scales generally overstate house chores, with a risk of gender bias. In addition, cultural bias can also be present, especially in countries where domestic workers such as cleaners or gardeners have a prominent role in the household. To reduce bias, one needs to take this contextual information into consideration when interpreting scores in the face of cognitive decline and/or behavioral change – and comparison to premorbid level of functioning is paramount (Figure 16.2). As such, ADL scales tend to not offer normative tables as seen in neuropsychological tests, because each individual should be compared to themselves. When assessing functional abilities we are examining change in the individual’s ability to perform their usual tasks, and from this standpoint, assessment of functional decline can offer a sensitive measure of change from premorbid functioning.

Competence in house chores can be culturally specific, and ADL assessments should be interpreted individually and with premorbid levels in mind. “Anunciacao” (Annunciation), by Luciana Comenote and Coletivo C.U.P.I.N.S (Central Unida de Pessoas Inventando Novas Saidas), 2011. Technique: Woodcut on Fabric.

Our experience in working in functional disability has led us to develop a functional and behavioral staging tool, which was developed particularly for FTD patients. By utilizing a data-driven approach (Rasch analysis), we were able to develop and validate a tool that could stage accurately FTD patients from a clinical perspective. Importantly, by relying on functional abilities and behavioral symptoms, the scale is not bound to floor effects seen on cognitive tests due to language deficits. The Frontotemporal Dementia Behavioral Rating Scale (FTDFRS) [6] is based on an interview to the proxy (most of the time a primary carer who is also a family member) and takes about 15–20 minutes to complete, depending on the severity of the patient. The FTDFRS can classify patients in six different stages: very mild; mild; moderate; severe; very severe; profound.

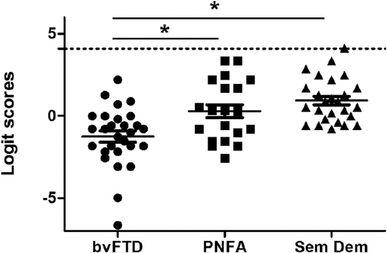

The FTDFRS [6] has demonstrated ability to differentiate between the three main FTD variants (Figure 16.3), where behavioural variant FTD (bvFTD) patients are much more severe than PPA patients when matched for length of symptoms. We have also demonstrated that the bvFTD patients reach the severe stages of dementia in about 5 years, while it can take up to 10 years for semantic variant PPA (svPPA) patients to reach the same level of dementia severity. Importantly, if comparing the FTDFRS with the original Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) [7], our scale demonstrates greater sensitivity to patients’ impairment and level of dependency to carers or environment (Figure 16.4). Finally, the FTDFRS is also more sensitive to functional deficits in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [8] than the original CDR.

Profiles of disease severity in behavioural variant FTD (bvFTD), non-fluent PPA (PNFA), and semantic variant PPA (Sem Dem) patients. From: Mioshi E, Hsieh S, Savage S, Hornberger M, Hodges JR (2010). Clinical staging and disease progression in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 74(20), 1591–7.

Proportion of FTD patients in each FRS severity category according to the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale ratings. From: Mioshi E, Hsieh S, Savage S, Hornberger M, Hodges JR (2010). Clinical staging and disease progression in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 74(20), 1591–7.

Importantly, the FTDFRS is not the only option in staging patients in FTD. The Mayo group has also addressed this gap by extending the CDR for FTD, which resulted in the CDR-FTLD [9]. The CDR-FTLD includes two additional domains, language and comportment, and has been shown to have greater sensitivity for detecting changes in FTD than the original CDR, with great applicability for future drug trials.

Patterns of functional impairment in FTD subtypes, and their progression

The underlying neural changes that lead to distinct initial symptoms in bvFTD and the PPAs, also lead to various patterns of functional disability. These impairments also progress in different degrees depending on the FTD variant (Figure 16.5). This section will present profiles of functional impairment by FTD subtype, and will also include a brief section on logopenic variant PPA, CBD, and PSP.

Percentage of FTD and AD patients presenting with different degrees of impairment on basic ADLs and instrumental ADLs. From: Mioshi E, Kipps CM, Dawson K, Mitchell J, Graham A, Hodges JR (2007). Activities of daily living in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 68(24), 2077–84.

Behavioral variant FTD

Impairment in executive functioning and ADL performance occurs early in the disease for patients with bvFTD [10]. We have shown [11, 12] a similar level of impairment in basic ADL and instrumental ADLs in bvFTD, but this finding is not universal [13]. This discrepancy is likely to be due to different methodologic approaches in instrument selection or inclusion of patients at different stages of the dementia. In general dementia, ADL decline follows a well-known pattern, in which instrumental ADLs are usually affected first, followed by late deficits in basic ADLs. However, this is usually not the case for bvFTD, where both instrumental complex tasks as well as basic ADLs are affected from disease onset. The great majority of bvFTD patients (90%) are impaired in basic ADL performance [11]. As such, impairment on basic ADLs features in the diagnostic criteria for FTD [14, 15].

In comparison with other FTD variants, bvFTD patients perform more poorly in both instrumental ADLs and basic ADLs than svPPA and non-fluent variant PPA (nfvPPA) patients in most activities, including household chores, shopping, finances, leisure, and self-care [11, 13, 16]. In comparison with AD, bvFTD patients show similar levels of instrumental ADL impairment, but more severe basic ADL impairment than AD patients when matched for length of symptoms. The rate of progression of functional disability is also marked in bvFTD, where patients decline more rapidly than other variants over a 12-month period [6, 12, 17, 18].

Assessment of functional decline in bvFTD is not only important because of its severity from the early stages, but also because it is not directly associated with cognitive deficits. In other words, high scores on standard cognitive tests, such as the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination or the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) can lead to an erroneous assumption that the patient is not very impaired at home or in the community. It has been demonstrated that bvFTD patients may continue to score relatively well on cognitive assessments when in reality there is marked worsening in the patient’s abilities to perform activities at home and in the community safely [19]. (Patients with PPA variants show a clear decline on these tests from an early stage, and this will be discussed below.) When the striking impairment to perform ADLs is added to a low or absent level of insight into their own changes, patients can become evidently vulnerable to scams and malicious behavior, but can also present risk to others around if not monitored closely.

Driving is usually one of the most distressing areas to address with patients and families. In most cases, speeding and risk-taking behavior have been suggested as being related to behaviors such as disinhibition and agitation [20, 21]. Arranging for a professional driving assessment allows for an objective assessment from an external party, and minimizes the chances of the patient blaming the loss of the license on the spouse or family. However, the removal of the driver’s license may not impact on their attempts to drive. Common issues with shopping are related to overspending, purchasing unnecessary items such as those shown on television commercials, paper advertisements, or even via door-to-door sellers at home – as a result of poor judgment and impulsivity [22]. In some extreme cases, patients might shoplift, which can be very distressing to the family. It is often reported that while the patient is able to go to the shops independently, they might ignore the shopping list, only returning with items which interest them (such as biscuits, lollies, or other favorite items). Impaired judgment can lead to mistakes in financial management, but the patient might be rigid about retaining their role as financial manager, refusing help, and in some cases hiding correspondences and bills received in the mail. bvFTD patients can become very prone to email scams, and many families have lost considerable amounts of money as a result of these behaviors. Inappropriate phone calls such as calling people or services multiple times a day, and disclosing credit card or personal details to telemarketers can occur quite often [22]. Changes in behavior may lead to over-medicating, or refusal to take medication [23, 24], which can become stressful scenarios for the family. Apathy and executive dysfunction are common symptoms that may impact on a person’s participation in meal preparation [24–26]. An important aspect to management of any of these behaviors is carer education about FTD and how the condition manifests in behaviors. Table 16.1 offers a number of strategies that might be useful in managing instrumental ADLs in bvFTD.

| Instrumental ADLs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| bvFTD | |||

| Driving | ✓ Hide car keys ✓ Disable the car and tell the person you are waiting on a mechanic ✓ Sell the person’s car and tell them it was stolen or is at the repair shop ✓ Store the car out of sight to reduce visual reminders [22] | Shopping | ✓ Provide the person with a limited shopping list with fewer items ✓ Notify local shops of the person’s condition and propensity to shop lift and make arrangements to return/pay for items ✓ Cancel or remove the person’s credit card ✓ Provide the person with a weekly allowance ✓ Organize for someone to accompany patient to the shops |

| Finance and correspondence | ✓ Redirect mail to a PO Box, family member, or a neighbor’s house ✓ Change passwords to online accounts to prevent any serious incidents of financial mismanagement [22] ✓ Email scams: check patient’s email account to monitor potential engagement with scammers | Telephone | ✓ Unplug home phone when carer is out to prevent unwanted telemarketing calls ✓ Contact telephone company to block telemarketing calls ✓ Redirect calls to house to the carer’s mobile phone ✓ Set up a PIN for outgoing calls – the telephone company can help |

| Medications | ✓ If multiple medications are required, use of a Webster-pack or Dosette box may assist with administration of correct prescriptions ✓ Liaise with the pharmacist about alternative forms of administration, such as adding liquid or powdered forms to food ✓ Carers might need to manage the person’s medications from an early stage | Housework | ✓ Set up an activity for a person, and assist them to begin the task (sometimes apathy may primarily impact on a person’s ability to initiate a task) ✓ Carer education around amending expectations about how much the person should participate or be engaged in an activity [22] |

| Meal preparation | Apathy ✓ Set up the activity for the person, and assist them to begin the task, for example, place out a chopping board, knife, and carrot, then demonstrate by cutting first slice ✓ If apathy is a more pervasive symptom, an important strategy may be around carer education, so they may amend their own expectations about how much the person can participate or be engaged in an activity [22] | Meal preparation (cont.) | Executive dysfunction ✓ Planning impairments may be addressed by providing a recipe “written” with step-by-step pictures, or by breaking the task down into more manageable steps, such as peeling the carrots or chopping the potatoes [70]. Providing aspects of an activity that a person can do allows them to remain actively involved in ADLs [67] |

Basic ADLs are also affected in bvFTD from an early stage, contrary to most dementias, where there is usually a clear gradient of loss from the most complex to the simplest tasks.

Neglect in personal hygiene is an early symptom, and can affect routines with showering, brushing teeth, and grooming (e.g., shaving, combing hair, and using makeup). This neglect worsens as the disease progresses [12, 24]. Patients often wear a reduced selection of outfits, or tend to repeat a favorite piece (e.g., shirt, dress, underwear), which can lead to refusal to change even when washing is obviously needed. Also, wearing inappropriate clothing can be a consequence of several deficits: inability to choose appropriate outfits for a specific occasion, inability to recognize weather conditions or even potentially changes in temperature regulation. Incontinence can occur quite early in the disease and can be the result of behaviors such as apathy, decreased insight, or even disinhibition, rather than a specific physiologic cause. Examples include passing urine sitting on the couch rather than getting up; passing urine while eating cake as the patient did not want to leave the table; using pot plants and rubbish bins as urinals in the care facility. Of note, it is important to consider that incontinence can also result from health conditions such as prostate enlargement or urinary tract infections, and therefore these should be ruled out as potential causes with the patient’s doctor. Eating habits are generally affected from an early stage, with changes in food preference being very common in bvFTD, in particular increased preference for sweet foods and carbohydrates [24, 27–29], which can lead to marked weight increase. In most cases, patients tend to seek out preferred foods, rummaging through the refrigerator and pantry, or even going shopping recurrently to obtain the item. Table 16.2 shows strategies that might be helpful in managing basic ADLs in bvFTD patients.

| Basic ADLs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| bvFTD | |||

| Hygiene | ✓ Prompting and reminding become a key requirement of carers in these situations ✓ Carers are often required to re-evaluate their own expectations of how frequently the person needs to shower or shave ✓ Some carers have successfully used sweets or chocolates as rewards for hygiene activities | Continence | ✓ Set up a toileting routine where patients use the toilet at regular intervals throughout the day and before bedtime ✓ If patient urinates in inappropriate places, place signs on these places directing the person to use the toilet |

| Dressing | ✓ Remove dirty clothes while the person is in the shower, and provide a clean, similar outfit ready to be donned when they get out. Some carers even purchase multiple copies of a favored shirt so it may be easily transferred for washing ✓ Where possible, carers should consider ignoring the clothes choice, i.e., if the patient is just at home, or if it’s a cool day and they are not at risk of overheating ✓ If it is really necessary for certain clothes to be worn for an occasion, provide an appropriate outfit ready for the person when they finish in the shower, while ensuring all other clothes are out of sight | Eating | ✓ Keeping food out of sight might be enough to deter overeating caused by utilization behavior [15, 23] ✓ Install a lock on the fridge and/or pantry to prevent unwanted rummaging if the behavior has escalated [22] ✓ Placing healthy snacks such as fruit or nuts visibly on the kitchen bench or table may catch the person’s attention before they reach the pantry or fridge |

Primary progressive aphasia: semantic variant

Impairments in semantic memory and difficulty recognizing faces, voices, or names are common in svPPA and impact on the person’s ability to engage in instrumental ADLs such as social events, using the telephone, and appropriately managing correspondence [11]. These impairments can ultimately result in early retirement if the person was in the workforce at diagnosis.

Patients with svPPA show similar rates of impairment to bvFTD and nfvPPA in instrumental ADLs; however, they differ in their performance of basic ADLs [11]. Patients with svPPA usually have preservation of basic ADLs for a number of years compared with instrumental ADLs, which are usually impaired from an early stage.

In terms of functional progression over time, svPPA patients have been reported to decline at a less rapid rate than both nfvPPA and bvFTD patients [8, 30, 31]. This is also seen when measuring dementia stages: svPPA patients are quite stable in disease progression for many years, from a functional perspective [6, 31].

On cognitive tests, patients with svPPA are often globally impaired owing to their language deficits; however, at home they often maintain their engagement in routine tasks until later into disease progression. This is likely to be associated with the rigid routines that are extremely common in patients with svPPA; future studies should address this potential relationship.

Ability to perform instrumental ADLs in svPPA is therefore well maintained for years, despite the evident semantic deficits and rigid behavior. Driving skills are often well preserved until the moderate stage. Impairments in language can pose a risk for these patients if they were to be involved in a car accident or altercation where they may have difficulty communicating with authorities. Ability to shop independently remains for some years if the patient is purchasing habitual items. Semantic impairments may eventually create difficulty with recognizing products and produce. Overspending is not a common issue in svPPA; patients in fact may become increasingly frugal with money, which often manifests as obsessive searching for “bargains.” Managing medications is also usually not a problem for svPPA patients for a number of years, which seems to be made possible by their ritualized routines. Meal preparation can be affected by deficits in semantic knowledge of kitchen implements and foods [32], and ability to perform household chores is often retained until the late stages of the dementia, often driven by compulsions such as the daily need to pack the dishwasher in a certain way [33]. Social outings tend to be greatly affected by changes in behavior, especially disinhibition. These behaviors may include (but are not limited to): approaching people or children they do not know when out in public, commenting loudly about the way people look, or providing bizarre demonstrations such as dancing or singing [34]. When disinhibition is pronounced, carers can become very embarrassed and may prefer to limit outings (see Case 2). Overall, patients with svPPA adhere to rigid, time-constrained routines, which in fact seem to facilitate their engagement in a limited range of activities [33, 35]. Narrowing of interests is another common symptom seen in svPPA patients, where they may develop a more focused, obsessive interest in only one or two activities – and will spend a large amount of time engaging within these [36], e.g., spending hours per day engaged with jigsaw puzzles [37]. Case 3 provides an example of a carer changing her own reaction to a situation, rather than trying to change the patient’s behavior. Attempting to interrupt a person’s rigid routine is likely to elicit distress, irritability, and aggression [36]. Table 16.3 contains a number of strategies that might be useful in managing instrumental ADLs in svPPA and nfvPPA.

Management strategies for instrumental ADLs in svPPA and nfvPPA

| Instrumental ADLs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| svPPA and nfvPPA | ||||

| Driving | ✓ Carry an official letter from the patient’s doctor or information card in the person’s wallet explaining their situation, and providing contact details of their carer, family members, or close friends ✓ Have the person wear a medical alert necklace or bracelet containing the patient’s address and emergency contact numbers [68] | Shopping | ✓ Include visual elements on a shopping list, e.g., cut the label from products at home which need replacing ✓ Carer education with a focus on coping strategies and thought modification to manage their own reactions to a behavior of little consequence, e.g., catalogue “bargain” hunting | |

| Finance and correspondence | ✓ When possible, support patients to maintain their involvement with previously held roles such as managing the finances to help them to retain a sense of independence and control ✓ Close family or friends may provide assistance through proofreading documents prior to the person sending them | Housework | ✓ Supporting patient may extend level of engagement in roles involving housework and garden [31] ✓ Relax the standard of performance to allow continued participation in activities, even if the person does the chore incorrectly. For example, someone may wash dishes in cold water with no detergent. In this case, the carer may ignore the mistakes, or may want to wash again when the person is not in the room. Either way, the patient has been allowed to continue contributing to household tasks | |

| Telephone | ✓ Preparing a script before making a phone call may provide some guidance, and instill some confidence ✓ Some patients with nfvPPA prefer to write emails or text messages rather than making phone calls as writing allows more time for the person to generate their message, while also providing spelling and grammatical software assistance ✓ Receiving written correspondence may be equally as beneficial to allow the person time to interpret the written message, rather than trying to quickly process spoken words without the visual cues provided by speaking with someone in person | Meal preparation | Semantic impairment ✓ Picture-based instructions using images of ingredients, implements, and the process steps may address semantic impairments [32] Apraxia ✓ Task breakdown may be useful in this situation; they may be able to peel vegetables, or assist by stirring. Monitor use of appliances and sharp or heavy items in the kitchen. Assist person where necessary (e.g., carrying heavy pots, or using knives), while allowing the person to continue with tasks they remain able to complete | |

| Leisure and outings | Disinhibition ✓ Carry little information cards to hand out to people explaining that their family member has a brain condition which causes behavioral changes ✓ Avoid public places, such as supermarkets, at peak times to reduce the possibility of any public demonstrations ✓ While at the supermarket, ensure the patient has a role such as pushing the trolley to keep them engaged ✓ Visit restaurants earlier, or call ahead to request a table in a quiet part of the restaurant to reduce the possibility for triggering the patient’s desire to demonstrate their “skills” to people, such as their lunge-walk ✓ If at the park with grandchildren, take a favorite snack or game which could be used as a distraction for the patient if other children arrive [22] Rigidity ✓ Working within the rigid routines of a person, rather than trying to cease them, is likely to generate a more positive outcome for both the person and the carer | Leisure and outings (cont.) | Communication impairments ✓ Planning ahead by only attending events with fewer people, and only planning to stay for a limited time may help with reducing chances of the person becoming overwhelmed and of social withdrawal ✓ Informing friends and family of the person’s condition prior to an event may help to generate a supportive environment, while also providing opportunity to impart some useful communication strategies ✓ Use of communication cards or boards, gestures, or language-based technologies tailored to specific social situations may support a person with PPA to participate [68] ✓ Avoid talking over the person ✓ Offer assistance with word-finding after allowing reasonable time for them to express the word themselves ✓ Allow more time to communicate ✓ Ensure you speak clearly, at an appropriate pace, tone, and volume ✓ Couple verbal communication with body language such as gestures, eye contact, and facial expressions ✓ Limit distractions such as ambient music or crowds ✓ Communicating in statements rather than questions can support a person to be involved in a conversation without feeling pressured to verbally contribute themselves | |

Ability to perform basic ADLs is well maintained in svPPA until the very late stages of dementia, even though patients might not be able to name products or to verbally communicate the activities they are intending to perform. Late in the disease, difficulties in differentiating products appear, e.g., patients can mistake shaving cream for toothpaste. As with all dementias, patients might refuse to perform personal hygiene tasks at the severe stages and excessive prompting often leads to increased stress and unsuccessful outcomes. Dressing issues might also appear later in the dementia. Changes in food preferences are also common in svPPA: restrictive dieting or rigidity with specific foods are common [25, 36], which can be accompanied by fixed times to set the table and eat. Secondary to their semantic deficits, patients may also consume unsafe items such as raw meat, mouldy food, or non-food items such as soap or a kitchen sponge in the severe stages of the dementia [38]. Strategies that might be helpful in managing basic ADLs in svPPA and nfvPPA are shown in Table 16.4.

Management strategies for basic ADLs in svPPA and nfvPPA

| Basic ADLs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| svPPA and nfvPPA | |||

| Hygiene | ✓ Remove any non-essential items from the bathroom ✓ Store items specific to one hygiene task, such as toothbrush and toothpaste, together in a clear, marked container. Labeling the container with a photo of the person doing that task will illustrate the contents and their correct use ✓ Confusion often occurs with varied packaging on products; ensure consistency in the replacement of any product, for example the same brand, size, and color of shampoo [71] ✓ Health professionals can assist a carer to modify their expectations about the person’s personal hygiene and to generate an appropriate care plan to match the person’s needs while limiting carer burden from unnecessary prompting and confrontations | Dressing | ✓ Remove dirty clothes while the person is in the shower, and provide a clean, similar outfit ready to be donned when they get out. Some carers even purchase multiple copies of a favored shirt so it may be easily transferred for washing ✓ Where possible, carers should consider ignoring the clothes choice, i.e., if the patient is just at home, or if it’s a cool day and they are not at risk of overheating ✓ If it is really necessary for certain clothes to be worn for an occasion, provide an appropriate outfit ready for the person when they finish in the shower, while ensuring all other clothes are out of sight |

| Continence | ✓ Continence strategies used in general dementia such as continence wear and the toileting schedules mentioned for bvFTD would be useful in these situations | Eating | ✓ Ensure food in the fridge is monitored according to expiry dates, and that foods such as raw meats are made inaccessible to the person [22] |

Primary progressive aphasia: non-fluent variant

Frank language dysfunction in nfvPPA leads to impairments in writing and reading and eventually mutism, with great impact on the ability of patients to participate in leisure activities such as social events and other interpersonal interactions [35]. The majority of patients with nfvPPA do not show any changes in their performance on basic ADLs for a number of years post-diagnosis, despite performing poorly on general cognitive assessments [13, 39, 40]. While patients with nfvPPA have relatively preserved basic ADLs, impairments in instrumental ADLs are common, ranging from mild to severe impairment by around two years into disease progression [39, 41].

Longitudinal changes to function over a 12-month period have recently been suggested to be more marked in nfvPPA than in svPPA [6]. In nfvPPA, clear associations between global cognition and functional disability have been demonstrated [39, 40], especially in cohorts of patients assessed longitudinally.

Instrumental ADLs are impaired from an early stage also in nfvPPA, though mostly secondary to language deficits. Driving skills are often preserved until late in the disease, unless apraxia appears. As with svPPA, impairments in language can become a risk for these patients if they were to be involved in a car accident where they may have difficulty communicating with others. Patients with nfvPPA may be able to continue managing financial tasks for a relatively long period into the disease. Telephone use tends to become an issue as patients avoid it, because of awareness of their communication limitations; many patients prefer to text or email, even if spelling mistakes are obvious. It is not exactly clear why nfvPPA patients reduce their participation in meal preparation, since they often maintain good semantic knowledge of kitchen-related items. It is likely that a combination of early apraxia and deficits in multitasking can hinder their ability to prepare meals [42]. The ability to perform household chores is often retained until late into the dementia, when other combined cognitive deficits impact on their ability to perform chores. Insight into their language deficits is a common cause of social withdrawal.

Basic ADLs are very well preserved for a large numbers of years in nfvPPA. However, once the patient reaches the severe stages, refusal to engage in personal hygiene tasks can occur as in most dementias. Incontinence does not usually appear until very late into disease progression, and can therefore be managed according to standard dementia practices. Eating and dietary changes are rarely seen in nfvPPA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree