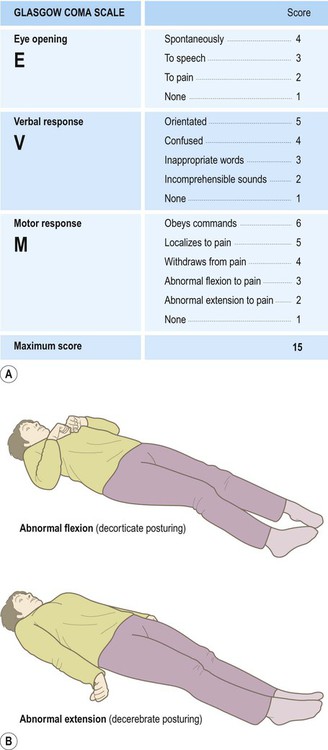

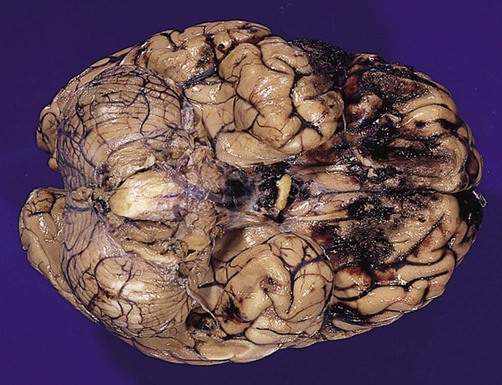

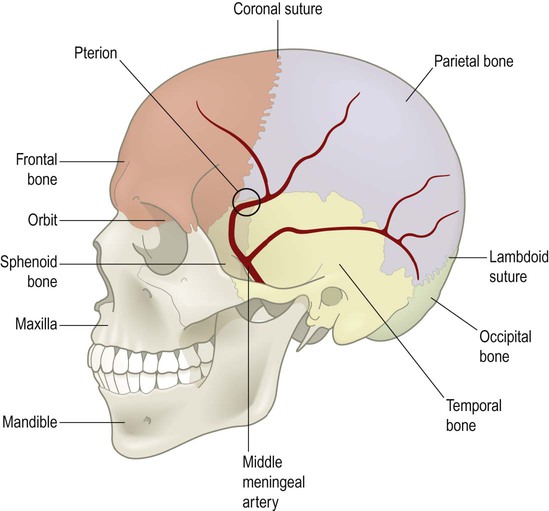

The best indicator of head injury severity is impairment of consciousness. This either reflects brain stem dysfunction or diffuse hemispheric damage. Level of consciousness is assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) which quantifies responses to verbal and painful stimuli in terms of eye opening, speech and movement (Fig. 9.1). The aggregate score ranges from a maximum of 15 (alert and orientated) to a minimum of 3 (comatose or dead). A GCS score of 13–15 corresponds to mild head injury, accounting for the majority of cases. A total score of 9–12 represents moderate head injury, whilst a score of 3–8 signifies severe head injury. In addition to providing an initial assessment of severity, any reduction in the GCS score is a sensitive indicator that the clinical state has deteriorated. This may signify development of a secondary complication requiring urgent intervention. The role of imaging in the assessment of head injury is discussed in Clinical Box 9.1. Factors that predict a less favourable outcome include increasing age (>60 years), an initial GCS score below 5, a fixed and dilated pupil, a prolonged period of hypotension/hypoxia or a haemorrhage requiring surgical decompression. Late complications may include hydrocephalus due to obstruction of CSF drainage pathways (see Ch. 2, Clinical Box 2.2) or seizures (Clinical Box 9.2). Cerebral contusions (bruising) and lacerations (tears) are common in traumatic brain injury, occurring in more than 90% of fatal cases. Contusions are most pronounced at the crests of gyri in the frontal and temporal lobes, particularly in places where the brain comes into contact with the irregular contours of the skull base (Fig. 9.2). Cerebral contusions may be associated with haemorrhage into the overlying subarachnoid or subdural spaces and if blood continues to accumulate it will begin to act as an intracranial mass lesion. The combination of a cerebral contusion with an overlying subdural haemorrhage is called a burst lobe. This most often occurs at the frontal and temporal poles. This typically occurs when the middle meningeal artery is torn by a skull fracture in the region of the pterion, where the bone is thin and is closely related to the underlying vessel (Fig. 9.4). Arterial blood escapes into the extradural space (between dura and bone) and strips the tightly adherent dura from the inner table of the cranial vault (Fig. 9.5).

Head injury

Clinical aspects

Assessment and management

(A) Response to verbal and painful stimuli is assessed in terms of eye opening, verbal response and motor response. The minimum score is 3 (even in death) and the maximum score is 15 (alert and orientated); (B) Abnormal flexion to pain (an ‘M’ score of 3 out of 5) is also known as decorticate posturing, whereas abnormal extension to pain (an ‘M’ score of 2 out of 5) is called decerebrate posturing. From Teasdale, G and Jennett, B: LANCET (ii) 81-83: (1974) with permission.

Outcome following head injury

Pathology of head injury

Cerebral contusions

They are particularly marked in the orbital cortex and frontal/temporal polar regions. From Prayson, R: Neuropathology 1e (Churchill Livingstone 2005) with permission.

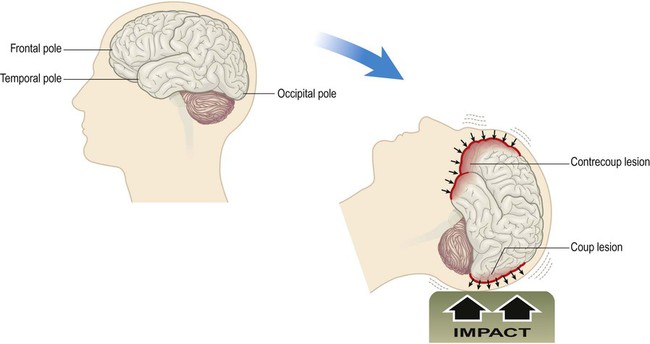

Coup and contrecoup lesions (Fig. 9.3)

Intracranial haemorrhage

Extradural haemorrhage

The underlying vessel is therefore vulnerable to damage in association with a skull fracture.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Head injury

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue