Hemiconvulsion-Hemiplegia-Epilepsy Syndrome

Alexis Arzimanoglou

Charlotte Dravet

Patrick Chauvel

Introduction

Hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia-epilepsy (HHE), described by Gastaut et al.17 in 1957, was not considered as a syndromic entity in the 1989 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification of epilepsies and epilepsy syndromes. Indeed, one could argue that the initial episode of a prolonged unilateral convulsion can be classified as a unique episode of a motor partial status, with hemiplegia as the main sequela. The later development of focal seizures can be considered, and consequently classified, as a form of partial symptomatic epilepsy. In 2001, HHE was introduced as a syndrome in the published report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology.12 In fact, it is the stereotyped sequence of events (hemiconvulsions followed by hemiplegia and leading to a focal epilepsy) that makes HHE “a complex of signs and symptoms that defines a unique epilepsy condition,” that is, a syndrome.

As mentioned, taken separately each of its components cannot be considered as an identifiable syndrome because they can be classified into other categories. However, as for progressive myoclonic epilepsies, maintaining HHE as a syndrome is still useful because of the unique characteristics of the condition and their importance when dealing with complex issues and concepts such as secondary epileptogenesis, role of febrile convulsions, and neuroprotection.

Historical Perspectives and Definitions

The sequence of prolonged hemiconvulsions (the term unilateral status could be used to differentiate them from focal status restricted to a body segment) immediately followed by hemiplegia and, secondarily, focal epileptic seizures was identified by Pierre Marie26 in 1885 within the setting of infantile infectious disorders and described by Gowers in 1886 as “posthemiplegic epilepsy.”18 Similar descriptions advocated a vascular13 or “acute encephalitic”7 etiology.

In 1957, Gastaut et al.17 grouped cases of hemiplegia in childhood following convulsions due to various causes (excluding cases of preexisting brain damage) and were the first to use the term HHE. In their series of 150 patients, they found that >80% of cases of chronic epilepsy occurred after a free interval of <1 year and 50% of cases of “psychomotor” epilepsy after >3 years. Partial seizures were considered to be of temporal origin. Further studies8,9,33,34 have demonstrated that the initial episode may be observed in various situations and that the subsequent partial epilepsy can be temporal, extratemporal, or multifocal.

The term hemiconvulsion-hemiplegia (HH) is often used to describe the initial stage of the syndrome. It is considered as appearing in a child without antecedents, usually before the age of 4 years. Using current ILAE classification criteria for the definition of syndromes, one cannot consider HH as an epilepsy syndrome, because it corresponds to a unique paroxysmal episode.

The incidence of HHE has declined considerably over the last 20 years. Between 1967 and 1978 the number of HHE cases in the district of Geneva decreased from 7.7 to 1.64 per 10,000 children (Beaumanoir, cited by Roger et al.35). A PubMed search reveals that the most recent publication of a series on HHE dates back in 198821; it reported on computed tomography (CT) and electroencephalogram (EEG) abnormalities in 25 children with post-hemiconvulsive hemiplegia hospitalized between 1968 and 1980. Since 1995 not more than ten small series or isolated case reports have been published. It is expected that it would be difficult for isolated cases to be accepted for publication. The lack of published large series, however, probably reflects the dramatic improvement in the acute treatment of prolonged seizures in young children. As a consequence, some children who experienced HH avoid motor sequelae and late-onset epilepsy, whereas others do not develop the full HHE clinical picture and are considered as focal epilepsies with antecedents of an acute, usually febrile, convulsive episode.

Age at Onset

The HH initial episode has its peak of incidence during the first 2 years of life; 60% to 85% of the cases occur between 5 months and 2 years of age, with only few patients who are 4 years or older.3,36 In approximately three fourths of patients, the HH episode evolves to the secondary appearance of partial epilepsy. The average interval from the prolonged initial convulsion to chronic epilepsy was 1 to 2 years, with 85% of the epilepsies having started within 3 years in one study.3 However, this series was biased in favor of the early onset of complex partial seizures, and these often occur 5 to 10 years after the initial episode.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Evaluation

The first stage of the syndrome, hemiconvulsion, constitutes a particular form of status epilepticus corresponding to the unilateral seizures described by Gastaut et al.15 As stated in the previous edition of this book and by Arzimanoglou et al.,6 this type of seizure deserves to be distinguished because it occurs frequently in infants and young children, diffuses to the whole of the affected side and can last 30 minutes or more (up >24 hours if untreated). In children, most of the long-lasting hemiconvulsions, particularly in the presence of fever, are the initial

epileptic manifestations,2,3,30 which explains the impossibility of prevention. Recognition of this type of seizure by general practitioners, pediatricians, and nurses is of primary importance because in most of the cases the outcome is favorable,27,39 provided treatment is administered early in the course of the seizure. The seizure is predominantly of the clonic type, with saccadic adversion of head and eyes to one side and unilateral, more or less rhythmic jerks of the limb muscles (with contralateral involvement), variable degree of impairment of consciousness, and autonomic symptoms (cyanosis, hyersalivation, respiratory dysfunction) of variable severity.

epileptic manifestations,2,3,30 which explains the impossibility of prevention. Recognition of this type of seizure by general practitioners, pediatricians, and nurses is of primary importance because in most of the cases the outcome is favorable,27,39 provided treatment is administered early in the course of the seizure. The seizure is predominantly of the clonic type, with saccadic adversion of head and eyes to one side and unilateral, more or less rhythmic jerks of the limb muscles (with contralateral involvement), variable degree of impairment of consciousness, and autonomic symptoms (cyanosis, hyersalivation, respiratory dysfunction) of variable severity.

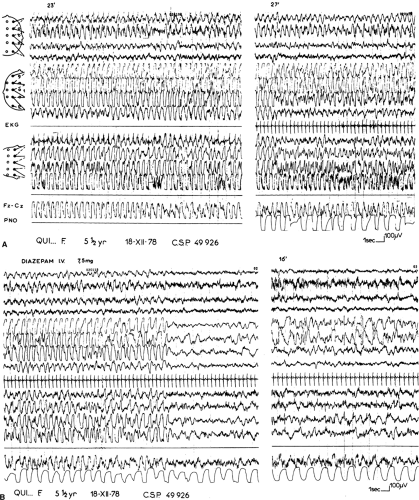

The ictal discharge consists of rhythmic (2–3/s) bilateral slow waves, with higher amplitude on the hemisphere contralateral to the clinical seizure. On this side they are intermingled with recruiting rhythms of 10 cycles/s, which predominate posteriorly (Fig. 1). Ictal EEG is variable because of changes in shape, frequency, and topography of the slow and fast components. Pseudorhythmic Spike-waves (SWs) contralateral to the clinical seizure, periodically interrupted by electrodecremental events of 1 to 2 seconds’ duration, also may occur. Polygraphic recordings do not demonstrate any consistent relationship between muscle jerks and spikes. Spontaneous seizure termination is brisk, with a brief extinction of all rhythms followed by delta waves of higher amplitude on the ictally engaged hemisphere alternating with short periods of suppression. On the opposite side, physiologic rhythms progressively reappear. At this time the hemiplegia is noted. When the seizure is stopped by intravenous diazepam, arrest of muscle jerks is immediate. The ictal discharge progressively vanishes, persisting longer on the ictally engaged hemisphere. Postictal asymmetry is obvious, with abundant drug-induced rapid rhythms invading the contralateral hemisphere.8

The second stage of the syndrome, hemiplegia, immediately follows the prolonged convulsive episode. It is initially flaccid and fairly massive but tends to become spastic and less marked as time passes. The minimum duration of the hemiplegia is arbitrarily set at <7 days, to separate it from the more common postictal or Todd paralysis. In 20% of the cases of Gastaut et al., the hemiplegia was not permanent and disappeared within 1 to 12 months. In our experience,6 some degree of spasticity, increased deep tendon reflexes, and pyramidal tract signs persist, even when the paralysis clears. The hemiplegia is usually predominant in the arm, but the face is constantly involved, an important sign that differentiates an acquired hemiplegia from a congenital one in cases of early onset.

The third component of HHE is focal epilepsy. The average interval from initial convulsions to chronic epilepsy is 1 to 4 years,17 with 85% of the epilepsies having started within 3 years of the first hemiconvulsive episode in one study.3 Vivaldi,43 in his series of 45 cases, reported a range of 1 month to 9 years after the acute episode. Approximately two thirds of the late seizures are focal seizures with alteration of consciousness.36,43 Focal seizures without alteration of consciousness, mainly clonic motor seizures, occur in approximately 30% of the patients; secondarily generalized seizures are reported in 20% and other episodes of status in approximately 10%.36 Gastaut et al. considered that the epilepsy is always made of focal seizures originating from the temporal lobe (previously called “psychomotor seizures”).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree