Fig. 33.1

Heparin-related intraparenchymal hemorrhage. The patient received large amounts of heparin during cardiac catheterization. Coronal CT image shows a large left frontal lobe hematoma with surrounding vasogenic edema

Fig. 33.2

Heparin-related subdural hematomas. The patient incurred head trauma. Axial CT image shows bilateral mixed attenuation subdural hematomas (arrowheads) and a right subgaleal hematoma (arrow)

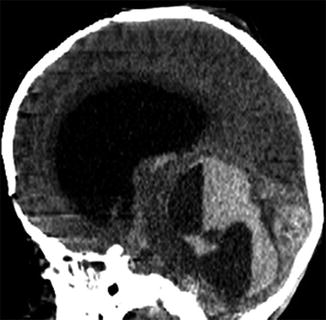

Fig. 33.3

ECMO-associated hemorrhage. Sagittal CT image shows large posterior fossa hematomas with associated obstructive hydrocephalus

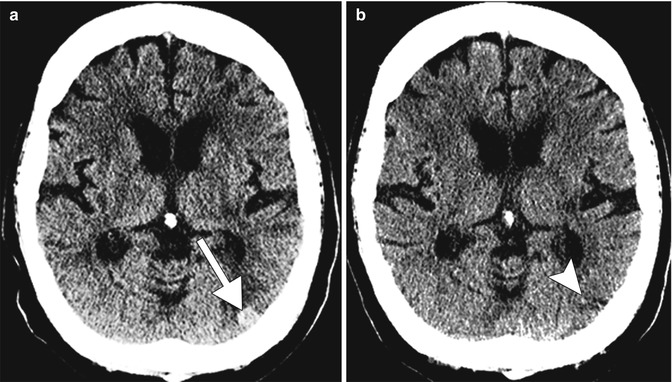

Fig. 33.4

Concurrent anticoagulation and metastatic disease. The patient has a history of metastatic lung cancer and was on heparin DVT prophylaxis. Axial CT image (a) shows hemorrhage that developed suddenly within a left occipital lobe metastasis (arrow) after instituting prophylactic heparin. The lesion (arrowhead) was barely perceptible not long previously (b)

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) occurs in 1–5 % of patients treated with heparin and can occur immediately, although usually occurs after several days of treatment. It is a life-threatening condition in which at least half of the patients develop arterial or venous thrombosis that can lead to amputation or death. In neuroimaging, the most common manifestation of HIT is venous sinus thrombosis, in which hyperattenuating venous structures can be encountered on non-contrast CT, although it is best demonstrated as filling defect on post-contrast imaging. This can occur in conjunction with venous infarct/hemorrhage in 50 % of cases and should be suspected in cases of infarcts appearing to evolve in a non-arterial distribution. Thrombus tends to form initially in a dural sinus and then propagate into deep cerebral and/or cortical veins. Once venous drainage is obstructed, venous pressure will rise, resulting in vasogenic edema and possibly parenchymal infarct and/or hemorrhage secondary to venous hypertension. If infarction occurs, cytotoxic edema will ensue. Venous sinus thrombosis is the presenting event of HIT in 3 % of cases.

If sinus thrombosis is suspected in a patient who is currently using or has recently used heparin, HIT must be excluded, since this condition represents an absolute contraindication to further anticoagulant therapy. Diagnosis of HIT is made primarily by detecting the presence of HIT antibodies, although a decrease in platelet count of >50 % is also considered diagnostic. Given their high risk of clot formation, patients receive antithrombotic therapy even in the absence of known thrombus. Treatment is continued until the platelet count has rebounded. Despite thrombocytopenia, increased bleeding is not seen in patients with HIT.

The first published clinical report of heparin-related osteopenia appeared in 1965. Griffith et al. described spontaneous vertebral and rib fractures in adult patients treated with 15,000–30,000 units daily for 6 months or longer. The effects were found to be reversible with the cessation of therapy. A more recent study of patients receiving heparin therapy during pregnancy showed no clinically significant osteoporosis, with approximately 1/3 of patients developing subclinical osteoporosis.

33.4 Differential Diagnosis

Intracranial hemorrhage. A broad differential diagnosis exists in the setting of acute, nontraumatic cerebral hemorrhage, and both clinical history as well as imaging findings are needed to arrive at the appropriate diagnosis (refer to Chaps. 2, 5, 16, 21, 30, 31, and 34). In addition to anticoagulation, hypertensive hemorrhage may also be considered in patients with the appropriate history. Hypertensive hemorrhages are typically parenchymal hemorrhages, commonly striatocapsular and thalamic. Amyloid angiopathy is an important consideration in older patients, especially those who are normotensive and present with lobar hemorrhage. On the other hand, parenchymal hemorrhage associated with enhancement may be secondary to bleeding related to a vascular malformation as well as hemorrhagic metastasis. Patient age, clinical history, and medical comorbidities are all vital tools that assist in determining the most likely etiology of an intracranial bleed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree