History and Introduction

Key Points

Willis and Moniz lived in very inauspicious times and circumstances. Using only the most primitive of tools, both left monumental legacies to medicine through their diligence, unflagging curiosity, and hard work with gifted colleagues.

The lessons of the Thorotrast debacle are as relevant today as they were in the 1930s. Well-intentioned medical devices can be very dangerous.

Thomas Willis (1621–1675)

Thomas Willis was born on January 27, 1621, in Great Bedwyn, a small village in Wiltshire, England, and died in London on November 11, 1675, having lived his life in what the ancient Chinese maledictum refers to as “interesting times.” He had a busy and productive life, taking a Bachelor of Arts degree at Oxford in 1639 at age 18, a Master of Arts in 1642, and a Bachelor of Medicine in 1646 (1). In 1657 he married Mary Fell, thus becoming the brother-in-law of the unlovable Dr. Fell of doggerel lore. Thomas and Mary had four children, only one of whom survived to adulthood. He is buried in the north transept of Westminster Abbey.

The 17th century, which encompassed his entire life span, was a period of unparalleled political upheaval in English history, featuring several civil and religious wars, usurpation by a wart-faced tyrant, crypto-Catholicism, gunpowder plots, Long Parliaments and Rump Parliaments, regicides and restorations (2). It was a time of internal feuds and external threats. Dutch agent provocateurs skulked louchely behind every hedgerow, and one could not throw a stone in any corner of the kingdom without hitting some popish agent plotting sedition of one form or another. To compound the misery of the populace, adultery was declared a capital offence in 1650 by the Puritan Parliament, although, curiously, only female transgressors could be found to receive the sentence. Otherwise, the courts were clogged with proceedings related to victimless crimes such as swearing and lechery. The population declined or at least stagnated at several reprises in the latter half of the century due to the effects of disease and “warres,” while roiling epidemics of plaque, smallpox, and typhus stalked the realm. In 1666, a massive fire—initially dismissed by the Mayor, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, as being of no greater merit than “A woman might piss it out”—destroyed the City of London. Under most circumstances, such a litany of political and natural disasters might account for the decline of a nation into penury and obscurity, but the 17th century in England was an anomalous period. England entered the age in the provincial homespun of a local dominant entity in an archipelago of isles off the coast of Europe, and despite all that happened somehow emerged from it on the brink of becoming a world empire.

It was an age in which giants such as Isaac Newton, William Napier, Christopher Wren, Robert Boyle, William Harvey, and Robert Hooke milled about in gangs. As a forum for sharing their discoveries, they founded the Royal Society, putting to the sword the long stultified medieval dogmatic approach to knowledge with its exclusive emphasis on rote learning and mind-numbing Aristotelian philosophy, and laid the foundation for the growth of modern science. Willis was one of that group of intellectuals, laboring throughout at his medical practice in the town of Oxford in the midst of political turmoil, which is not to say that he was oblivious to the political events around him. His family was identified with the Royalist side, and it is known that he took a break from his studies during the first Civil War to drill with the Royalist Oxford militia. His father died in 1643 “snatcht away by the Contagion of a Camp-feaver” during a siege of Oxford (3). Following this we are told that Willis the Younger “betook himself to Oxford, being the Tents of the King as well as the Muses; where listing himself a souldier in the University Legions, he received Pay for some years, until the Cause of the Best Prince being overcome, Cromwell’s tyranny afforded to this wretched nation a peace more cruel than any war” (4).

Thomas Willis began his medical studies at Oxford in 1643 at a time when the curriculum at English universities was a hide-bound 3-year course of lectures in Galenic and Aristotelian cant, declaimed every Tuesday and Friday morning at eight o’ clock by the Regius Professor of Medicine. Students had to submit evidence that they has been present at the dissection by a surgeon of two corpses, usually procured after the Lenten assizes, but medical knowledge as such was not required. Indeed, an alternative pathway to graduation was available through the offices of the Archbishop of Canterbury, who had the power to bestow a medical degree. European universities were, by comparison, considered much advanced, and ambitious students preferred to go abroad, as had, for instance, William Harvey in an earlier generation.

Fortunately for Willis, the effects of war were disruptive to this long-observed monotony of intellectual abeyance. The student population at Oxford dwindled, traditions of long usage went unobserved, and graduations grew scarce. The university buildings were converted to granaries and barracks, an epidemic of typhus ravaged the town and its hinterland, and a fire destroyed over 300 houses. The impact on Willis was to liberate him to become something of a medical autodidact, free of the pedagogic constraints that had existed hitherto. When the royal court of Charles I removed to Oxford in 1642, the royal physician William Harvey accompanied him and was appointed to the Oxford faculty, becoming a neighbor of Willis on Merton Street. His controversial and iconoclastic teachings on the circulation and other medical topics had been held in bad odor for many years by the old guard, but his arrival and appointment at Oxford at a time of such great tumult must have had an impact on the willingness of the establishment to embrace change. It seems probable that the loosening effect of the events of this period had a great influence on Willis.

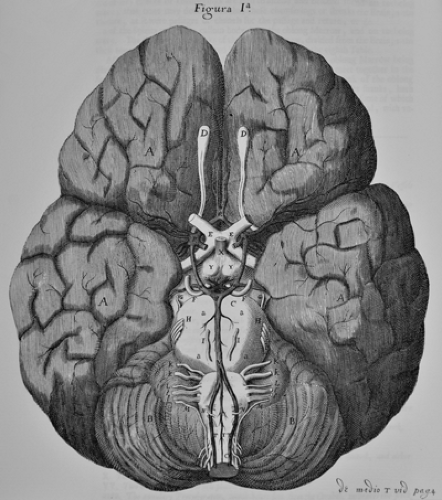

From the modern coign of vantage, Willis’s greatest contribution was his description of the anatomy of the brain, Cerebri Anatome (1664) (5), written in collaboration with Christopher Wren, Thomas Millington, and Richard Lower. This book described the anatomy of the cerebral hemispheres, brainstem, and spine with unprecedented clarity (Fig. 1-1). He cataloged the cranial nerves almost akin to how we currently enumerate them. The hippocampus, thalamus, colliculi, and superficial landmarks of the medulla are described accurately. He speculated on the regulatory functions of the brainstem and the likelihood that the gyral pattern of the human brain accounted for higher cognitive abilities compared with lower mammals (6). The capacity of the arterial pentagon at the base of the brain to compensate for loss of one carotid artery by compensation of flow from the other side is discussed by Willis too. The book was an immediate success for him and published in several editions in England and on the continent. This work did not, however, happen in isolation. Willis was a prolific writer of several texts throughout his professional life, demonstrating an unending curiosity about his patients and their symptoms, and exercising his ability to describe the phenomena that he witnessed in a new light, unfettered by the conventional Aristotelian wisdom. All commonplace medical symptoms were grist to his mill. He described myasthenia gravis, the sweetness of urine in diabetes (chamber-pot dropsy), schizophrenia, epilepsy, mental retardation, and scurvy. He wrote on the comparative anatomy of dogs, oysters, and earthworms. He described the phenomenon of paracusis, which still bears his eponym. He described puerperal fever, narcolepsy, general paralysis of the insane, and whooping cough. While the medical value of these books is now severely dated, naturally, the volume and breadth of his work stand as testament to his greatness.

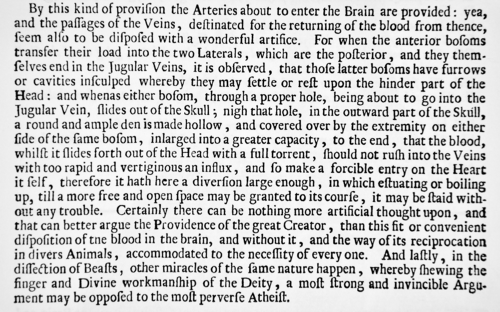

Willis had several key aspects of his professional life, which contributed to his well-deserved historical status and success. Primarily, he was intensely curious, and could see and describe patients and their difficulties in simple terms without a preordained bias. Secondly, he was a hard worker. His medical practice was highly successful and lucrative, not least due to his unflagging energy and willingness to make distant house calls beyond the confines of the city. In 1667, the year Willis left Oxford for London, the poll-tax records reveal that his income was 300 pounds, an enormous sum when the annual salary, for instance, of the college cook was a munificent two pounds. Thirdly, he did not work alone and was fortunate to live among friends and colleagues of a similar bent. The illustrations of Cerebri Anatome, for instance, are remarkably accurate and lucid, by modern standards, but these were executed by Wren and Lower. Furthermore, much of the description of comparative vascular anatomy in Willis’s work, where he contrasts the human cerebral and spinal vessels and neuroanatomy with that of dogs, also owes much to his collaborators (Fig. 1-2). Based on the work of Harvey concerning the physiology of the circulation, Wren had developed, some years previously, a technique for accessing the circulation of animals using goose quills during investigation of the effects of injecting ale and opium into dogs. This technique was used by Willis and Lower for injecting India ink and alcohol pigments into the circulation of dogs and human cadaveric specimens and may also have contributed to the better preservation of his postmortem materials, compared with the inaccurate and simplistic descriptions of early writers such as Vesalius. Incidentally, a refinement of this quill technique would lead to the first instance of blood transfusion later in the same decade by Richard Lower and Edmund King (1667). Clearly, Willis’s innovative contributions could not have happened without the collaboration of a remarkable coterie of friends and colleagues, all of whom were destined for greatness too in other fields of invention, science, and architecture.

The most famous incident in the life of Thomas Willis concerned the ripping yarn of Anne Green, amounting to the first recorded instance of successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation (7). Anne Green was a lowly rustic wench of 22 years, toiling away in domestic service at the home of a member of the local nobility, Sir Thomas Read, when she got herself into an unfortunate state at the villainous hands of Mr. Geoffrey Read, grandson of Sir Thomas. The issue of this dilemma, a male child, was stillborn, and Anne Green was haled before the 1650 assizes on charges of infanticide, where a death sentence was handed down. Accordingly, on a cold Saturday morn in December, Anne Green was brought to the Oxford Cattle Yard, a place of execution, where “after singing a Psalme and something said in justification of herself, as to the fact for which she was to suffer and touching the Lewdness of the family wherein she lately lived, she was turn’d off the Ladder, hanging by the neck for the space of almost halfe an houre, some of her friends in the meantime thumping her on the breast, others hanging with all their weight upon her legs, sometimes lifting her up, then pulling her downe againe with a sudden jerke, thereby the sooner to dispatch her out of her paine, insomuch that the Unde-Sheriffe fearing lest they should break the rope, forebad them to do so any longer.” Apparently dead, her body was placed in a coffin and “carried away in order to be anatomiz’d by some yong physitians” (8,3). According to the 1636 Royal Charter to the university from Charles I, the Oxford professor of anatomy held claim to any corpse following an execution held within 21 miles of the town, and thus she was brought to the home of Dr. William Petty, where he, Willis, and some other local physicians were to perform an autopsy. However, when the lid of the coffin was removed, some signs of life were evident, and the party broke up into two schools of thought. The one, including the apparently incompetent executioner and some of the young men present, thought to finish her off by administering a good series of kicks in the abdomen and chest. The other, under Petty and Willis, prevailed in saving her, and after bleeding her five ounces of blood, tickling her throat with a feather to encourage breathing, and administration of restorative cordials, she was “put to bed to a warme woman.” She began speaking within 24 hours, and was eating solid food at four days, recovering completely in time, except for a period of amnesia surrounding the hanging. She was granted a reprieve and subsequently a pardon, with Petty and Willis testifying on her behalf that her baby could not have survived his deformities. Anne Green lived for 15 more years apparently the object of some felicitous notoriety, married and bore three children, and lived a more comfortable life as a result of her historic adventure by virtue of her father’s enterprise in charging an admission fee for curious visitors who wished to see her.

It was the sort of thing that one did in the 17th century.

Égas Moniz (1874–1955)

António Caetano de Abreu Freire was born on November 29, 1874, in Avanca, Portugal, the eldest son of an old aristocratic family (9). While a student at the University of Coimbra, he took as pen name that of a legendary Portuguese hero, Égas Moniz, which he continued to use throughout his life. He graduated from medical school in 1899. Following studies in Bordeaux and Paris under Babinski, Pierre Marie, and Dejérine, he assumed the Chair of Neurology in Lisbon in 1911, a position he held until his retirement in 1944. Most of us would be reasonably content with as much accomplishment for one lifetime. However, Égas Moniz packed several internationally successful careers into one lifetime, to a degree that a litany of his accomplishments beggars belief. There are those who might say that early 20th-century Portugal was a less auspicious playground for providing the political and social tumult that fostered Willis’s success in 17th-century England, but Moniz had the capacity to make his own times very interesting nonetheless. He died in 1955. It is fascinating to review his life accomplishments and to realize that while he was productive throughout his entire lifespan, the work for which he remains famous (cerebral angiography) and for which he won the Nobel Prize (white matter leucotomy) did not commence until he was into his 50s.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree