Continuum of family-focused psychiatric agency and workforce activities.

The second dimension of Figure 28.1 outlines the work that might be undertaken in a family-focused psychiatric setting. We propose that all workers must acquire a “basic family skill set” with the most basic practice being that the worker engages with parents regarding their parenting and their children. For example, on intake to the service, we believe that a worker must inquire “Do you have children?” and “Are they currently safely in the care of someone?” Considering the importance of involving families in routine care, this is a bare minimum practice requirement for all workers. We also believe the basic skill set must include being able to assess a parent’s parenting skill and the family circumstances in which the children are living (Berman and Heru, 2005). It has been recommended that this minimum skill set include a process for identifying a service user’s children, the ability to initiate relationships with the service user’s family members, an assessment of the parents’, children’s and family’s basic needs, the provision of mental health literacy to each family member, collaborative practice with other key agencies, and clear and sensitive procedures for referrals within confidentiality agreements (Foster et al., 2012; Maybery and Reupert, 2009).

Further along the continuum is the provision of psychoeducation to parents, children, and families. Psychoeducation typically focuses on education about mental illness and treatment and has been shown to be particularly effective in the treatment of schizophrenia by reducing relapse and readmission rates and reducing the burden on family members (McFarlane et al., 2003). Another important worker skill is delivering family-focused strategies that address early intervention and the prevention of mental illness in children. A recent meta-analysis of the impact of family interventions on children concluded that “the risk of developing the same mental illness as the parent was decreased by 40%” (Siegenthaler et al., 2012). These prevention interventions are generally empowering for the parent, are enjoyable for the mental health worker, and are commonly brief (e.g., 2–5 sessions) and integrated with the worker’s current practice. The interventions aim to give practitioners the tools to engage with parents and children and to develop parents’ strategies for talking to their children about mental illness, promoting child and family strengths, and typically empowering parents in their parenting role.

Constraints on family-focused practice

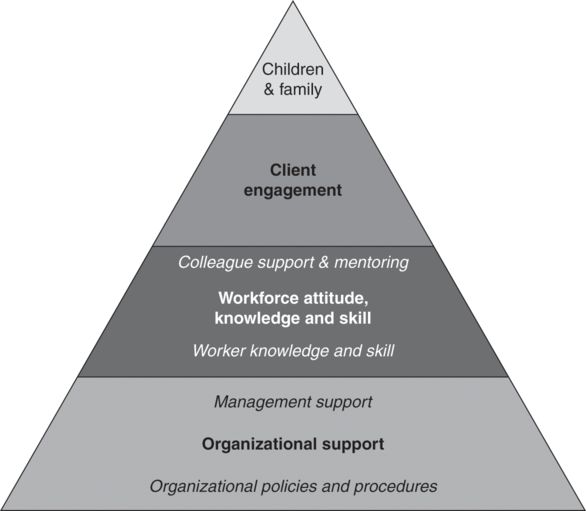

The efficacy of family-focused approaches has empirical support. In a meta-analysis, Dunst et al. (2007) found that the more family-focused workers were, the more service users were satisfied with workers and their programs, and had stronger self-efficacy beliefs. However, while the relevance and importance of family-focused practice has been highlighted in the previous section, the literature indicates multiple barriers to workers undertaking this work. In a systematic review of the literature, Maybery and Reupert (2009) summarized the literature (see Figure 28.2 above) according to the organization, the workforce, and the parent and family members. While discussed in detail elsewhere (see Maybery and Reupert, 2009), the key points can be summarized in the following list:

organizational support: The bedrock for workforce change is policies and management support that acknowledge the families and children of service users and encourage family-focused work.

workforce attitude, knowledge, and skill: Ensuring that the mental health workforce is skilled and knowledgeable about the impact of parental mental illness on families and children, and is able to respond with family-focused practices.

Points influencing family-focused workforce change (taken from Maybery and Reupert, 2009).

Other factors have been considered important including interagency collaboration (Maybery and Reupert, 2009) and personal factors as highlighted by more accomplished nurses at family-focused practice drawing upon their personal attributes, including their own parenting, life, and work experience (Grant, 2014). In addition, nurses working in a community setting undertook many more family-focused practices than those working in the acute, inpatient psychiatric setting (Grant, 2014). Profession differences have also been noted, with social workers being found to engage in more family-focused practice than psychiatric nurses and psychologists (Maybery et al., 2014). Furthermore, the greatest learning need in these professions in regard to family-focused practices has been identified for psychologists as knowledge about parenting, for general practitioners as knowledge about how to support families, and for nurses and social workers as knowledge about parenting and child development. Interestingly, knowledge about parenting was rated as the greatest learning need for all professions (Whitman et al., 2009).

International workforce responses to family-focused practice

To illustrate the evidence on family-focused care and practice in various contexts, the following section briefly outlines the psychiatric workforce situation in several different countries. The “state of play” is outlined for each country including where most effort has been centered. Finally, recommendations for the direction that each country could take to increase family-focused practice in the next 5–10 years are outlined.

Australia

Australian efforts to enhance workforce capacity have focused upon resource development, policy changes, and workforce research. The Australian National Initiative, Children of Parents with a Mental Illness (COPMI), has developed many resources of training materials for parents, children, families, and the mental health workforce. Generally, these have been online e-learning resources focused on raising awareness, training in specific interventions, or providing information for parents, children, and families (see www.copmi.net.au/ and Chapter 27 for more details). The COPMI initiative has also harnessed the work across Australia of many groups and “champions” focused on parental mental illness that have systematically advocated a focus on families within their individual workplaces. COPMI have also led the way in terms of policy with the document “Principles and Actions for Services and People Working with Children of Parents with a Mental Illness” (AICAFMHA, 2004). Increasingly, government policy is also beginning to acknowledge parenting and child-related needs. Multiple research studies have also been undertaken over the last ten years in Australia, including practice audits, workforce surveys, and evaluation studies (e.g., Reupert et al., 2011).

At the same time, more needs to be done in Australia to systemically identify the parenting status of clients, and to ensure that appropriate referral and intervention programs are in place to address the needs of families. A goal for Australia might be to ensure that all psychiatric workers are routinely taking the first step in the continuum in Figure 28.1 (i.e., asking, “Are you a parent, are your children safe, do they require some support?”), and that all parents, children, and families receive basic psychoeducation and family-centered interventions such as “Family Focus” or “Let’s Talk About Children.”

Canada

One of the most “grass-roots” efforts to improve workforce responses to families in Canada has been the development of community-based forums. Sponsored by a community of practice in British Columbia known as the Provincial Working Group on Supporting Families with Parental Mental Illness, forums have brought together practitioners from professional and paraprofessional ranks in adult mental health, child and youth mental health, child welfare, and schools along with family members with lived experience. Guided by a manual, community self-assessment encourages forum attendees to move from education to action based on the situation in their community. Evaluation has shown shifts in worker practice including a greater belief in the ability of families despite dealing with mental illness and greater passion for their work. Similar collaborative efforts at a systems level are typified by work in Manitoba by Elaine Mordoch, who brought together policymakers from the various agencies and universities to develop a strategy for inquiry and service to families with parental mental illness.

Interest in Ulysses Agreements (advance care plans) has assembled mental health workers and child welfare workers for case-specific action and learning. Anecdotal information from a Ulysses Agreement project in the Fraser Health Region, British Columbia, has demonstrated the strong desire of child welfare workers to respond supportively to parents with mental illness. However, these same child welfare workers have a perceived need for outside specialized staff, knowledgeable about mental illness and child development and skilled in wraparound-collaborative care models. A project in Toronto initiated in 2014 has brought dedicated adult mental health staff into a child welfare agency for a team approach to address the need of the child welfare system to appropriately deal with parental mental health factors.

Since 2010, policy development in British Columbia has been prompted by the publication of a 10-year mental health plan, “Healthy Minds, Healthy People,” which outlines key practice strategies related to parental mental illness. Moreover, policy and practice have been shaped by the tragic murder of three children by their father, who suffered from an undiagnosed mental illness and substance misuse. The document “Safe Relationships, Safe Children” and subsequent action plans have led to pilot projects directed by the government that require agencies delivering adult mental-health, child-welfare, and women’s domestic services to plan for ways to work collaboratively, identify mental illness and substance misuse in parents, and collaboratively consider the needs of children. Through these high-level initiatives, which were largely driven by a voluntary workforce, family-focused practice is now on the cusp of becoming required practice. Finally, the Institute for Families, a national organization led by parents with mental illness, has sponsored a first consensus conference (2014), “Family Smart.” Unique to this project is its consumer leadership and efforts to advance a set of principles regarding practice and organization that can be identified as “Family Smart.” These efforts promise a metric by which mental health organizations and practice can be assessed in relation to their degree of appropriate family-centered care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree